Hayashi, Tadamasa

Avant son adoption en 1870

Lecture : Hayashi Tadamasa

7 cité d'Hauteville

65 rue de la Victoire

14-15, 10-chо̄me, Kobiki-chо̄

Dans le quartier actuel du théâtre Enbujо̄ à Shinbashi

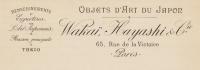

Venu à Paris pour l'Exposition universelle de 1878 ; Propriétaire d'une boutique appelée "Objets d'art anciens du Japon, T. Hayashi" sise au 65, rue de la Victoire à Paris (en 1895) ; Membre de "Meiji bijutsu kai" (Société artistique de Meiji)

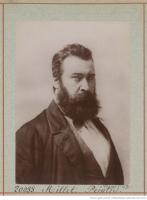

Naissance et milieu social

La date aujourd’hui admise pour la naissance de Hayashi Tadamasa est le 11 décembre 1853 (7e jour du 11e mois de l’an 6 de l’ère Kaei) (Koyama-Richard, 1997, p. 234, p. 249). Son lieu de naissance, Takaoka, dans l’ancien fief d’Echichû, au sein de la puissante province de Kaga, est notamment réputé pour l’art des métaux, un domaine que Hayashi cherchera par la suite à encourager et à développer par ses activités commerciales. Il est né dans une famille de médecins de père en fils, spécialistes des méthodes occidentales. Son grand-père, Nagasaki Kôsai (1799-1863), est resté célèbre dans ce domaine. Shigeji (Tadamasa) est adopté, en 1870, selon une coutume courante au Japon, par son cousin Hayashi Tachû, qui occupe alors un poste important dans l’administration régionale, dans l’idée qu’il y ferait une carrière à son tour. Il prend le nom de Hayashi durant cette période. Le milieu d’origine de Hayashi Tadamasa est un milieu cultivé, mais d’une culture scientifique marginale dans le Japon féodal de l’époque d’Edo ; c’est un provincial de surcroît. Son adoption doit assurer sa promotion sociale, mais son cousin est bientôt destitué de ses fonctions.

Formation

Selon Edmond de Goncourt (1822-1896), Hayashi lui aurait confié avoir été attiré par la France en raison de son intérêt pour Napoléon Bonaparte (1769-1821), découvert dans des livres d’un médecin hollandais, « maître » de son père (Journal des Goncourt, 28 juillet 1895). Selon Brigitte Koyama-Richard, il s’agirait en fait d’un maître japonais de médecine occidentale (Koyama-Richard, 1997, p. 178). Puis, il se rend à Tôkyô à l’instigation de son cousin Hayashi Tachû et s’inscrit d’abord en 1870 à l’école de français, Tatsuridô, fondée en 1867 et dirigée par Murakami Eishun (1811-1890), lui aussi issu d’une famille de médecins, et médecin lui-même (Kigi, 2009, p. 369). En 1871, il s’inscrit pour le cycle universitaire de la Daigaku Nankô, qui deviendra en 1877 l’Université de Tôkyô (Tôkyô Daigaku). Les cours y sont donnés par des professeurs étrangers dans leurs langues respectives. Hayashi se spécialise dans la langue française, qu’il étudie pendant sept années. Ayant choisi de ne pas étudier d’autre spécialité que la langue et gêné à cause de cela pour obtenir une bourse, Hayashi abandonne ses études et répond à une proposition de poste de traducteur au service de la société de commerce Kiritsu kôshô kaisha fondée en 1874, avec pour but de vendre à l’étranger des articles d’artisanat moderne japonais.

Carrière professionnelle

Hayashi Tadamasa suit une trajectoire professionnelle qui le mène du métier d’interprète au service de la Kiritsu kôshô kaisha à la profession de marchand d’art, qu’il cumulera avec la participation aux côtés de Wakai à l’organisation d’expositions consacrées à l’art japonais (pour la société et dans le cadre de différentes expositions universelles) ou à des artistes japonais en France, au Japon, mais aussi aux États-Unis par exemple. Tout au long de sa carrière, Hayashi a beaucoup voyagé, traversant à plusieurs reprises de nombreux pays d’Europe, ainsi que la Russie, les États-Unis et/ou encore la Chine en 1888 (Kigi, 1987, p. 376). Ces voyages sont intimement liés à sa carrière professionnelle.

Envoyé à Paris à l’occasion de l’exposition universelle en 1878, il arrive en mars de Yokohama, qu’il a quittée le 29 janvier de la même année, et travaille auprès de Wakai Kanesaburô (1834-1908) (Koyama-Richard, 1997, p. 239). L’exposition organisée par celui-ci au Trocadéro a sûrement été l’occasion pour Hayashi de rencontrer les principaux collectionneurs français d’art japonais. Hayashi, aidé par sa maîtrise du français (ce qui n’est pas le cas de Wakai), qui le fait inviter en tant qu’interprète, va se faire ainsi rapidement un « carnet d’adresses » dans le milieu des collectionneurs et des artistes parisiens. Il rencontre cette année-là Edmond de Goncourt chez Philippe Burty (1830-1890) (Journal des Goncourt, 28 novembre 1878 ; Koyama-Richard, 2001, p. 46-47), deux hommes qui joueront un rôle essentiel pour lui.

Les débuts

En 1881, il rentre à nouveau à la Kiritsu kôshô kaisha à la demande de Wakai. Celui-ci, n’ayant plus de nouvelles de la société mère, décide de rentrer au Japon. En février 1882, Hayashi et Wakai fondent ensemble une société, affiliée au consortium Mitsui, et organisent la vente des stocks invendus de l’Exposition universelle de 1878. Hayashi travaille aussi comme ’interprète au prince Arisugawa no Miya (Taruhito, 1835-1895) de passage en France. Il aide à la préparation d’une exposition de la société de défense et de promotion des arts Ryûchikai (société de l’Étang du dragon) à Paris. En décembre, l’entreprise de Hayashi et Wakai se sépare de la Mitsui Bussan (Kigi, 2009, p. 373).

À partir de 1881, Hayashi apporte son aide à Louis Gonse (1846-1921) pour la rédaction de son ouvrage L’Art japonais, qui paraît en 1883, ainsi que pour l’Exposition Rétrospective de l’art japonais, la même année.

En janvier 1884, il ouvre un magasin à son propre nom situé dans la Cité d’Hauteville dans le 10e arrondissement. En juillet, il s’associe à Wakai, qui rentre au Japon, et envoie des objets à Paris. C’est le début de la Société Wakai-Hayashi. Selon Kigi Yasuko, l’activité de Hayashi était orientée vers la vente d’objets d’art, en particulier de céramiques chinoises notamment ,et de laques (Kigi, 2009, p. 70, p. 86 et sqs). Il fréquente le salon de la princesse Mathilde (1820-1904) et visite à nouveau l’Europe : Londres, l’Allemagne, la Hollande, et la Belgique notamment. La même année, la Kiritsu kôshô kaisha ferme son agence de Paris. Hayashi rencontre le peintre et collectionneur Raphaël Collin (1850-1916). C’est Hayashi qui présentera à ce dernier les jeunes peintres japonais. Hayashi ne semble pas avoir en revanche réussi ni même essayé de vendre les œuvres de ces artistes en France, mais plutôt à les faire reconnaître au Japon.

En janvier 1886, il ouvre une boutique 65 rue de la Victoire et fonde une société en février. En mars, il fait un rapport auprès des fonderies de Takaoka (sa ville natale) sur les attentes de la clientèle occidentale. En 1889, Wakai décide de rentrer au Japon ; lui et Hayashi se séparent et ce dernier monte sa propre entreprise, la société T. Hayashi, qui est active en 1890 (Koyama-Richard, 1997, p. 243).

L’apogée

Après un séjour aux États-Unis, Hayashi rentre à Paris en mai, puis retourne au Japon avec des œuvres de Kuroda Seiki (1866-1924), en compagnie de Yamamoto Hôsui (1850-1906) et de Gôda Kiyoshi (1862-1938). Il rentre à Paris en novembre (Kigi, 1987, p. 373. Hayashi défendra constamment les peintres japonais dans le style occidental (yôga). Il s’intéresse à l’aide apportée aux artistes par les gouvernements européens ; c’est lui qui aurait suggéré à l’homme d’État le prince Itô Hirobumi (1841-1909) la création du système des artistes de la maison impériale (Kigi, 2001, p. 13).

En 1888, Hayashi retourne au Japon, via la Chine, et se marie avec une jeune fille de 19 ans, (il en a 34), serveuse au restaurant Koyôkan (Koyama-Richard, 1997, p. 243 ; Kigi, 2009, p. 376). Elle conduira ses affaires à Tôkyô tandis qu’il continue de partager sa vie à Paris avec une certaine Suzanne, dite « Madame Hayashi », dont il se séparera peu après, parce qu’elle le trompait en son absence avec l’imprimeur Charles Gillot (1853-1903), selon Edmond de Goncourt (Journal des Goncourt, 12 janvier 1899 ; Koyama-Richard, 1997, p. 243).

Les années 1890-1900 marquent le sommet de la carrière de Hayashi, mais pas forcément la réussite financière. Ces années voient les collectionneurs américains s’éprendre des estampes et payer pour elles des sommes parfois très importantes. Ce sera d’ailleurs une période où la cote de l’art japonais s’envole dans les salles de ventes à Paris. On estime qu’en 11 ans et 218 livraisons, Hayashi exportera quelque 166 000 estampes et 9 708 livres illustrés (Emery, 2022 d’après Segi, 1980). Cependant, le prix des estampes ne tarde pas à monter aussi au Japon et rendent l’approvisionnement du marchand plus difficile, et les marges de profit plus réduites (Koyama-Richard, 1997, p. 189 ; et 2001, p. 111).

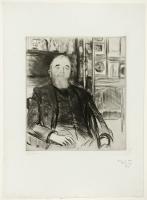

La même année, Albert Bartholomé (1848-1928) réalise un masque en bronze de Hayashi, qu’il a sans doute connu par Edgar Degas (1834-1916), lequel possédait un exemplaire en plâtre (localisation actuelle inconnue). Les bronzes sont signés et datés de 1892. Un exemplaire est exposé en 1894 au Salon de la Société nationale des Beaux-Arts, au Champ-de-Mars. Un exemplaire en bronze noir est conservé au musée de la Dentelle, à Calais. Un autre est dans une collection particulière, à Paris, un, enfin, est conservé au musée de Takaoka. L’exemplaire du musée d’Orsay est en bronze à patine rouge ; il a été acquis par la Société des amis du musée en 1990 (Paris, Musée d’Orsay, inv. RF 4303) (Koyama-Richard, 1997, p. 246).

En 1893, Hayashi est nommé commissaire du pavillon japonais à l’Exposition de Chicago (Columbus Centennial Exhibition). Le groupe des douze faucons sur un perchoir, dessiné et financé par Hayashi et réalisé par le fondeur Suzuki Chôkichi (1848-1919), exposé à Chicago, représente un échec financier pour Hayashi, qui ne parvient pas à le vendre. Après avoir été confiée au collectionneur allemand Ernst Grosse, l’œuvre rendue à la veuve d’Hayashi. Elle est conservée aujourd’hui au Musée national d’art moderne de Tôkyô (Kigi, 2009, p. 195 ; Koyama-Richard, 1998, p. 195). Hayashi rentre à Paris en compagnie de Bing au printemps 1894. En 1897, Hayashi participe à la publication Les affiches étrangères illustrées, pour la partie japonaise.

Les dernières années

Après 1897, Hayashi se trouve confronté à des difficultés financières et cherche à élargir ses affaires à d’autres types de négoces. Il se rend alors en Russie pour étudier de potentielles affaires pétrolières à réaliser (Koyama-Richard, 2002, p. 138-139). Après l’Exposition universelle de 1900, Hayashi est décoré comme commandeur de la Légion d’honneur par la France (décret du 10 novembre 1900) (Koyama-Richard, 1997, p. 199). En janvier 1902, après la mort de son frère, Hagiwara, il ferme son magasin, organise la vente de ses fonds à Paris, lors de ventes publiques en juin 1902 et février 1903 (voir catalogues de vente).

En mars 1905, il rentre définitivement au Japon. Il a le projet d’un musée. Il tombe malade, se remet. Il meurt à Tôkyô le 10 avril 1906.

L’héritage de Hayashi

Hayashi a joui longtemps d’une plus grande notoriété en France qu’au Japon. Les décorations françaises qu’il a reçues sont plus honorifiques que celles qu’il a reçues au Japon. Dans son pays d’origine, son action en tant que marchand reste controversée et ses efforts pour faire connaître l’art occidental auprès de ses concitoyens n’ont guère été couronnés de succès. Il a défendu avec sincérité les estampes japonaises et les arts décoratifs du Japon qui étaient l’essentiel, dès ses débuts, des articles qu’il importait vers la France. L’article de 1886 dans le Paris illustré (dont l’illustration de couverture, reproduite d’une estampe de Keisai Eisen [1790-1840] représentant une courtisane, sera copiée par Vincent Van Gogh) est très marqué par la vision occidentale courante à l’époque qui accorde une importance majeure à l’école Ukiyo-e et aux arts décoratifs. L’exposition rétrospective de 1900, avec de objets provenant des collections impériales, a sans doute été une révélation, pour lui y compris ; c’est en tout cas ce qu’il laisse entendre dans la conférence qu’il donne en 1900 à cette occasion ; il y souligne les progrès considérables faits dans la connaissance de l’art japonais ancien (Hayashi, T., 1903). Akiko Mabuchi a relevé toutefois que dans le compte-rendu de cette conférence, 20 lignes sont consacrées aux règne de l’impératrice Jingû et 26 à celui de l’empereur Kuanmu, qui appartiennent à la mythologie, contre 19 pour la période Fujiwara et 11 seulement pour l’ensemble de la période des Tokugawa (1603-1867), donnant ainsi sans aucun fondement historique une très grande place à la lignée impériale, et presque aucune à l’aristocratie militaire, dans l’histoire de l’art japonais (Mabuchi, 2001, p. 43). Son discours, ardemment patriotique, souligne le caractère original de l’art japonais, même lorsqu’il imite des modèles étrangers, et proclame sa supériorité sur l’art des autres nations asiatiques : Chinois, Coréens, et « Hindous ». Le patriotisme de Hayashi est aussi ce qui semble le caractériser aux yeux de ses contemporains, notamment Koechlin (Koechlin, 1930). Hayashi doit en effet sa carrière au nouveau régime impérial ainsi qu’à l’ouverture du Japon ; il défend son pays et le nouveau régime impérial ; c’est en même temps un admirateur de la modernité occidentale ; il soutient activement les artisans et les peintres contemporains japonais de l’école de peinture occidentale (yôga), et s’irrite des lenteurs du Japon à se réformer. Malgré ses contributions, Hayashi n’est pas un historien de l’art japonais ; il entrera en conflit avec l’historien de l’art américain Ernest Fenollosa (1853-1906). Son expertise n’est pas non plus sans lacune, si on considère les attributions des objets conservés au MNAAG. En revanche, Hayashi a côtoyé ou influencé les principaux collectionneurs d’art japonais en Europe. Il a participé, surtout par le biais de la documentation et de traductions, à des publications qui ont eu un écho très large en France, telles que l’Art japonais, (1883) de Louis Gonse, ainsi qu’aux ouvrages de Goncourt Outamar o: Le Peintre des maisons vertes (1891) et Hokusai: l’art japonais du XVIIIe siècle, (1896). Ces ouvrages n’auraient pu être menés à bien sans son aide. Il a aussi côtoyé les artistes les plus novateurs de son temps, en Occident, (comme Manet, Monet ou Pissarro, entre autres) mais aussi au Japon (Yamamoto Hôsui, Kuroda Seiki et bien d’autres). Hayashi a été non seulement un des acteurs essentiels du japonisme, un des deux grands marchands d’art japonais avec Bing à Paris, mais aussi une figure exemplaire du nouveau Japon de Meiji et de sa rencontre avec le reste du monde au tournant du XIXe et du XXe siècle.

Article rédigé par Michel Maucuer

Birth and social environment

The date agreed upon today for the birth of Hayashi Tadamasa is December 11, 1853 (7th day of the 11th month of the year 6 of the Kaei era) (Koyama-Richard, 1997, p. 234, p. 249). His birthplace, Takaoka, in the former stronghold of Echichû, within the powerful province of Kaga, was particularly renowned for the art of metalwork, a field that Hayashi would later seek to encourage and develop through his commercial activities. He was born into a family of doctors, the practice passed along from father to son, and he specialised in Western methods. His grandfather, Nagasaki Kôsai (1799-1863), was famous in this field. Shigeji (Tadamasa) was adopted in 1870, according to a common custom in Japan, by his cousin Hayashi Tachû, who then held an important position in the regional administration with the idea that he would in turn have a career there. During this period, he took the name Hayashi. Hayashi Tadamasa's background was cultivated but belonged to a marginal scientific culture in feudal Japan of the Edo period; he was moreover provincial. His adoption was meant to contribute to his social advancement, but his cousin was soon thereafter dismissed from his post.

Education

According to Edmond de Goncourt (1822-1896), Hayashi confided to him that he was attracted to France because of his interest in Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821), whom he had discovered in the books of a Dutch doctor, a "teacher" of his father (Journal des Goncourt, July 28, 1895). According to Brigitte Koyama-Richard, it was rather through a Japanese master of Western medicine (Koyama-Richard, 1997, p. 178). He went to Tokyo at the instigation of his cousin Hayashi Tachû and first enrolled at the French school, Tatsuridô, in 1870. This school was founded in 1867 and was directed by Murakami Eishun (1811-1890) who also came from a family of doctors and was a doctor himself (Kigi, 2009, p. 369). In 1871, he enrolled in the university cycle at Daigaku Nankô, which in 1877 became the University of Tokyo (Tôkyô Daigaku). Classes were given by foreign teachers in their respective languages. Hayashi majored in the French language, which he studied for seven years. Because he chose not to study any specialty other than language, he had trouble obtaining a scholarship. Hayashi therefore abandoned his studies and responded to a job offer as a translator in the service of the trading company Kiritsu kôshô kaisha, founded in 1874, with the aim of selling Japanese modern handicrafts abroad.

Professional Career

Hayashi Tadamasa followed a professional trajectory that led him from the profession of interpreter in the service of the Kiritsu kôshô kaisha to the profession of art dealer, which he would combine with participation alongside Wakai in the organisation of exhibitions devoted to Japanese art (for the company and within the framework of various universal exhibitions) or to Japanese artists in France, Japan, but also, for example, in the United States. Throughout his career, Hayashi traveled extensively, traversing numerous European countries on several occasions, as well as Russia, the United States, and even China in 1888 (Kigi, 1987, p. 376). These trips were closely linked to his professional career.

Hayashi was sent to Paris on the occasion of the Exposition Universelle in 1878, he arrived in March from Yokohama, which he left on January 29 of the same year, and worked with Wakai Kanesaburô (1834-1908) (Koyama-Richard , 1997, p. 239). The exhibition he organised at the Trocadéro was certainly an opportunity for Hayashi to meet the main French collectors of Japanese art. Aided by his mastery of French (unlike Wakai), the reason why he had been invited as an interpreter, Hayashi could quickly create an "address book" among collectors and Parisian artists. That year, he met Edmond de Goncourt at Philippe Burty (1830-1890) (Journal des Goncourt, November 28, 1878; Koyama-Richard, 2001, p. 46-47), two men who would play an essential role for him.

The Beginnings

In 1881, he returned to the Kiritsu kôshô kaisha again at the request of Wakai. The latter, having no more news from the parent company, decided to return to Japan. In February 1882, Hayashi and Wakai founded a company together, affiliated with the Mitsui consortium, and organised the sale of unsold stocks from the 1878 exhibition. Hayashi also worked as an interpreter for Prince Arisugawa no Miya (Taruhito, 1835-1895), who was passing through France. He helped prepare an exhibition for the Ryūchikai Arts Defense and Promotion Society (Dragon Pond Society) in Paris. In December, Hayashi and Wakai's company separated from Mitsui Bussan (Kigi, 2009, p. 373).

From 1881, Hayashi helped Louis Gonse (1846-1921) to prepare his book L’Art japonais, which appeared in 1883, as well as with the Exposition Rétrospective de l’art japonais, the same year.

In January 1884, he opened a store in his own name located in the Cité d'Hauteville in the 10th arrondissement. In July, he joined forces with Wakai, who had returned to Japan and was sending objects to Paris. This was the beginning of the Wakai-Hayashi Society. According to Kigi Yasuko, Hayashi's activity was oriented towards the sale of works of art, in particular Chinese ceramics, and lacquers (Kigi, 2009, p. 70, p. 86 et seq.). He frequented the salon of Princess Mathilde (1820-1904) and again visited Europe: London, Germany, Holland, and Belgium in particular. The same year, the Kiritsu kôshô kaisha closed its Paris agency. Hayashi met the painter and collector Raphaël Collin (1850-1916). It was Hayashi who introduced him to the young Japanese painters. On the other hand, Hayashi does not seem to have succeeded or even tried to sell the works of these artists in France, but rather to have made efforts to gain their recognition in Japan.

In January 1886, he opened a shop at 65 rue de la Victoire and founded a company in February. In March, he reported to the foundries of Takaoka (his hometown) on the expectations of Western customers. In 1889, Wakai decided to return to Japan; he and Hayashi separated and the latter set up his own company, the T. Hayashi company, which was active in 1890 (Koyama-Richard, 1997, p. 243).

The Apogee

After a stay in the United States, Hayashi returned to Paris in May, and then returned to Japan with works by Kuroda Seiki (1866-1924), in the company of Yamamoto Hôsui (1850-1906) and Gôda Kiyoshi (1862-1938). He returned to Paris in November (Kigi, 1987, p. 373). Hayashi constantly defended Japanese painters in the Western style (yôga). He was interested in the aid given to artists by European governments; it was he who suggested the creation of the system of artists of the imperial household (Kigi, 2001, p. 13) to the statesman Prince Itô Hirobumi (1841-1909).

In 1888, Hayashi returned to Japan, via China, and married a 19-year-old girl (he was 34), a waitress at the Koyôkan restaurant (Koyama-Richard, 1997, p. 243; Kigi, 2009, p. 376). She would conduct his business in Tokyo while he continued to share his life in Paris with a certain Suzanne, known as "Madame Hayashi", from whom he would separate shortly thereafter, as she cheated on him in his absence with the printer Charles Gillot (1853-1903), according to Edmond de Goncourt (Journal des Goncourt, January 12, 1899; Koyama-Richard, 1997, p. 243).

The years 1890-1900 mark the height of Hayashi's career, but not necessarily of his financial success. During this time, American collectors fell in love with prints and sometimes paid very large sums for them. It was also a period when the price of Japanese art soared in auction rooms in Paris. It is estimated that in 11 years and 218 deliveries, Hayashi exported some 166,000 prints and 9,708 illustrated books (Emery, 2022 after Segi, 1980). However, the price of prints soon rose in Japan as well, which made it more difficult for the dealer to supply them, and led to lower profit margins (Koyama-Richard, 1997, p. 189; and 2001, p. 111).

The same year, Albert Bartholomé (1848-1928) made a bronze mask of Hayashi, which he probably knew from Edgar Degas (1834-1916), who owned a plaster copy (current location unknown). The bronzes are signed and dated 1892. A copy was exhibited in 1894 at the Salon de la Société nationale des Beaux-Arts, at Champ-de-Mars. A black bronze example is kept at the Musée de la Dentelle (the Museum of Lace) in Calais. Another is in a private collection in Paris, and another is kept in the museum of Takaoka. The copy in the Musée d'Orsay is in bronze with a red patina; it was acquired by the Société des amis du musée in 1990 (Paris, Musée d'Orsay, inv. RF 4303) (Koyama-Richard, 1997, p. 246).

In 1893, Hayashi was appointed curator of the Japanese pavilion at the Columbus Centennial Exhibition in Chicago. The group of twelve falcons on a perch, designed and financed by Hayashi and produced by the founder Suzuki Chôkichi (1848-1919), exhibited in Chicago, represents a financial failure for Hayashi, who failed to sell it. After being entrusted to the German collector Ernst Grosse, the work returned to Hayashi's widow. It is now kept at the National Museum of Modern Art in Tokyo (Kigi, 2009, p. 195; Koyama-Richard, 1998, p. 195). Hayashi returned to Paris in the company of Bing in the spring of 1894. In 1897, Hayashi participated in the publication Les affiches étrangères illustrées, for the Japanese section.

The Final Years

After 1897, Hayashi found himself faced with financial difficulties and sought to expand his business to other types of trade. He went to Russia to study potential oil deals (Koyama-Richard, 2002, p. 138-139). After the Exposition universelle of 1900, Hayashi was decorated as a Commandeur in the Légion d’honneur of France (decree of November 10, 1900) (Koyama-Richard, 1997, p. 199). In January 1902, after the death of his brother, Hagiwara, he closed his store and organised the sale of his holdings in Paris, during public sales in June 1902 and February 1903 (see sale catalogues).

In March 1905, he returned to Japan for good. He had an idea for a museum. He fell ill, then recovered. He died in Tokyo on April 10, 1906.

Hayashi's Legacy

Hayashi has long enjoyed greater notoriety in France than in Japan. The French decorations he received bestowed greater honours than those he received in Japan. In his country of origin, his action as a dealer remained controversial and his efforts to make Western art known to his fellow citizens were not crowned with success. He sincerely defended Japanese prints and the decorative arts of Japan, which were the main items, from the start, of the items he imported to France. The 1886 article in Le Paris illustré (whose cover illustration of a courtesan, reproduced from a print by Keisai Eisen [1790-1840], would be copied by Vincent Van Gogh) is strongly marked by the Western vision current in the era that placed great importance on the Ukiyo-e school and the decorative arts. The retrospective exhibition of 1900, including objects from the imperial collections, was undoubtedly a revelation for him as well; at least so he suggests in the lecture he gave on this occasion, in which he underlines the considerable progress made in the knowledge of ancient Japanese art (Hayashi, T., 1903). Akiko Mabuchi noted, however, that in the report of this lecture, 20 lines are devoted to the reign of Empress Jingû and 26 to that of Emperor Kuanmu, which belong to mythology, against 19 for the Fujiwara period and 11 only for the whole of the Tokugawa period (1603-1867), thus giving, without any historical foundation, a very large place to the imperial line, and almost none to the military aristocracy, in the history of Japanese art (Mabuchi, 2001, p. 43). His ardently patriotic speech underlines the original character of Japanese art, even when it imitates foreign models, and proclaims its superiority over the art of other Asian nations: Chinese, Koreans, and "Hindus". Hayashi's patriotism was also what seemed to characterise him in the eyes of his contemporaries, notably Koechlin (Koechlin, 1930). Hayashi indeed owed his career to the new imperial regime as well as to the opening of Japan; he defended his country and the new imperial regime; he was at the same time an admirer of Western modernity; he actively supported contemporary Japanese craftsmen and painters of the Western school of painting (yôga), and was irritated by Japan's slowness to reform. Despite his contributions, Hayashi was not a historian of Japanese art; he would come into conflict with the American art historian Ernest Fenollosa (1853-1906). His expertise is not without gaps either, if we consider the attributions of the objects kept at the MNAAG. On the other hand, Hayashi rubbed shoulders with or influenced the main collectors of Japanese art in Europe. He participated, especially through documentation and translations, in publications that had a very wide echo in France, such as Art japonais (1883) by Louis Gonse, as well as works by the Goncourt brothers Outamar o: Le Peintre des maisons vertes (1891) and Hokusai: l’art japonais du XVIIIe siècle (1883). These works would not have been possible without his help. He also rubbed shoulders with the most innovative artists of his time, in the West (Manet, Monet, and Pissarro, among others) as well as in Japan (Yamamoto Hôsui, Kuroda Seiki, and many others). Hayashi was not only one of the key players in Japonisme and one of the two great Japanese art dealers in Paris, along with Bing, but also an exemplary figure of Meiji's new Japan and its encounter with the rest of the world at the turn of the 19th and of the 20th centuries.

Article by Michel Maucuer (Translated by Jennifer Donnelly)

Hayashi sert d'interprète à Paris auprès de Kawaji Toshiyoshi (1834-1879) qui étudie l'organisation de la police. En septembre, Hayashi accompagne le reste de la délégation japonaise et visite en leur compagnie la Belgique, la Hollande, l’Allemagne, l’Autriche, la Russie. Il rentre à Paris en mars 1880 (Kigi, 1987, p. 372).

Séjour à Bruxelles. Travaille probablement pour la société de commerce Kiritsu (Kiryû) kôshô kaisha.

En juillet (cf. lettre de Anderson du 22/07/1885 adressée chez Hart), Hayashi est, depuis quelques semaines sans doute (selon Burty, cf. Emery, à paraître 2022) à Londres. Il travaille sur les collections du British Museum et vraisemblablement du Victoria & Albert, et auprès du collectionneur Ernest Hart (1835-1898).

[Objets commercialisés]

[Objets commercialisés]

[Objets commercialisés] Période des Trois Royaumes et postérieur.

Charles Haviland fréquente assidument la boutique de Tadamasa Hayashi, ils correspondent régulièrement et Haviland lui achète de nombreux objets. (Source : notice Agorha "Charles Haviland" rédigée par Laurens et Tristan d'Albis).

J. L. Bowen, par une lettre signée du 1 juin 1896, demande à Hayashi une introduction auprès de Charles Haviland et de Louis Gonse pour voir leurs collections de laques. (Source : notice Agorha "Charles Haviland" rédigée par Laurens et Tristan d’Albis )

Philippe Burty fréquente Tadamasa Hayashi.

Le musée d’Ennery possède une partie de la correspondance entre Hayashi et Burty ainsi que des archives de Philippe Burty, consultables à la bibliothèque du Musée Guimet.

(Sources : Notices Agorha "Philippe Burty" rédigée par Léa Ponchel et "Hayashi Tadamasa" rédigée par Michel Maucuer).

Notice catalogue BNF : https://catalogue.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb13525237z.public

Notice anciennement mutualisée avec les Ressources de notices personnes issues de la bibliothèque numérique