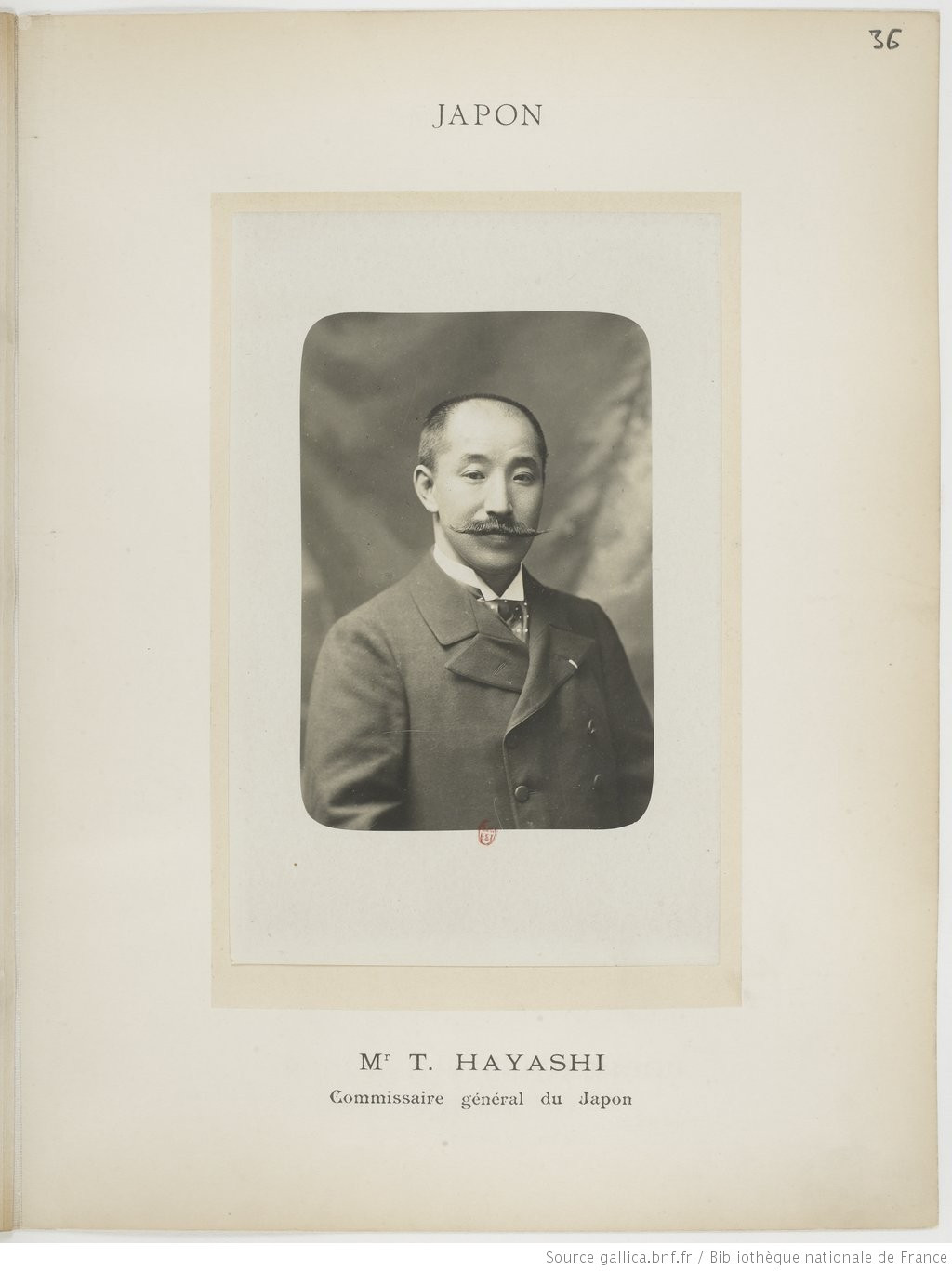

HAYASHI Tadamasa (EN)

Biographical Article

Birth and Social Environment

The date agreed upon today for the birth of Hayashi Tadamasa is December 11, 1853 (7th day of the 11th month of the year 6 of the Kaei era) (Koyama-Richard, 1997, p. 234, p. 249). His birthplace, Takaoka, in the former stronghold of Echichû, within the powerful province of Kaga, was particularly renowned for the art of metalwork, a field that Hayashi would later seek to encourage and develop through his commercial activities. He was born into a family of doctors, the practice passed along from father to son, and he specialised in Western methods. His grandfather, Nagasaki Kôsai (1799-1863), was famous in this field. Shigeji (Tadamasa) was adopted in 1870, according to a common custom in Japan, by his cousin Hayashi Tachû, who then held an important position in the regional administration with the idea that he would in turn have a career there. During this period, he took the name Hayashi. Hayashi Tadamasa's background was cultivated but belonged to a marginal scientific culture in feudal Japan of the Edo period; he was moreover provincial. His adoption was meant to contribute to his social advancement, but his cousin was soon thereafter dismissed from his post.

Education

According to Edmond de Goncourt (1822-1896), Hayashi confided to him that he was attracted to France because of his interest in Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821), whom he had discovered in the books of a Dutch doctor, a "teacher" of his father (Journal des Goncourt, July 28, 1895). According to Brigitte Koyama-Richard, it was rather through a Japanese master of Western medicine (Koyama-Richard, 1997, p. 178). He went to Tokyo at the instigation of his cousin Hayashi Tachû and first enrolled at the French school, Tatsuridô, in 1870. This school was founded in 1867 and was directed by Murakami Eishun (1811-1890) who also came from a family of doctors and was a doctor himself (Kigi, 2009, p. 369). In 1871, he enrolled in the university cycle at Daigaku Nankô, which in 1877 became the University of Tokyo (Tôkyô Daigaku). Classes were given by foreign teachers in their respective languages. Hayashi majored in the French language, which he studied for seven years. Because he chose not to study any specialty other than language, he had trouble obtaining a scholarship. Hayashi therefore abandoned his studies and responded to a job offer as a translator in the service of the trading company Kiritsu kôshô kaisha, founded in 1874, with the aim of selling Japanese modern handicrafts abroad.

Professional Career

Hayashi Tadamasa followed a professional trajectory that led him from the profession of interpreter in the service of the Kiritsu kôshô kaisha to the profession of art dealer, which he would combine with participation alongside Wakai in the organisation of exhibitions devoted to Japanese art (for the company and within the framework of various universal exhibitions) or to Japanese artists in France, Japan, but also, for example, in the United States. Throughout his career, Hayashi traveled extensively, traversing numerous European countries on several occasions, as well as Russia, the United States, and even China in 1888 (Kigi, 1987, p. 376). These trips were closely linked to his professional career.

Hayashi was sent to Paris on the occasion of the Exposition Universelle in 1878, he arrived in March from Yokohama, which he left on January 29 of the same year, and worked with Wakai Kanesaburô (1834-1908) (Koyama-Richard , 1997, p. 239). The exhibition he organised at the Trocadéro was certainly an opportunity for Hayashi to meet the main French collectors of Japanese art. Aided by his mastery of French (unlike Wakai), the reason why he had been invited as an interpreter, Hayashi could quickly create an "address book" among collectors and Parisian artists. That year, he met Edmond de Goncourt at Philippe Burty (1830-1890) (Journal des Goncourt, November 28, 1878; Koyama-Richard, 2001, p. 46-47), two men who would play an essential role for him.

The Beginnings

In 1881, he returned to the Kiritsu kôshô kaisha again at the request of Wakai. The latter, having no more news from the parent company, decided to return to Japan. In February 1882, Hayashi and Wakai founded a company together, affiliated with the Mitsui consortium, and organised the sale of unsold stocks from the 1878 exhibition. Hayashi also worked as an interpreter for Prince Arisugawa no Miya (Taruhito, 1835-1895), who was passing through France. He helped prepare an exhibition for the Ryūchikai Arts Defense and Promotion Society (Dragon Pond Society) in Paris. In December, Hayashi and Wakai's company separated from Mitsui Bussan (Kigi, 2009, p. 373).

From 1881, Hayashi helped Louis Gonse (1846-1921) to prepare his book L’Art japonais, which appeared in 1883, as well as with the Exposition Rétrospective de l’art japonais, the same year.

In January 1884, he opened a store in his own name located in the Cité d'Hauteville in the 10th arrondissement. In July, he joined forces with Wakai, who had returned to Japan and was sending objects to Paris. This was the beginning of the Wakai-Hayashi Society. According to Kigi Yasuko, Hayashi's activity was oriented towards the sale of works of art, in particular Chinese ceramics, and lacquers (Kigi, 2009, p. 70, p. 86 et seq.). He frequented the salon of Princess Mathilde (1820-1904) and again visited Europe: London, Germany, Holland, and Belgium in particular. The same year, the Kiritsu kôshô kaisha closed its Paris agency. Hayashi met the painter and collector Raphaël Collin (1850-1916). It was Hayashi who introduced him to the young Japanese painters. On the other hand, Hayashi does not seem to have succeeded or even tried to sell the works of these artists in France, but rather to have made efforts to gain their recognition in Japan.

In January 1886, he opened a shop at 65 rue de la Victoire and founded a company in February. In March, he reported to the foundries of Takaoka (his hometown) on the expectations of Western customers. In 1889, Wakai decided to return to Japan; he and Hayashi separated and the latter set up his own company, the T. Hayashi company, which was active in 1890 (Koyama-Richard, 1997, p. 243).

The Apogee

After a stay in the United States, Hayashi returned to Paris in May, and then returned to Japan with works by Kuroda Seiki (1866-1924), in the company of Yamamoto Hôsui (1850-1906) and Gôda Kiyoshi (1862-1938). He returned to Paris in November (Kigi, 1987, p. 373). Hayashi constantly defended Japanese painters in the Western style (yôga). He was interested in the aid given to artists by European governments; it was he who suggested the creation of the system of artists of the imperial household (Kigi, 2001, p. 13) to the statesman Prince Itô Hirobumi (1841-1909).

In 1888, Hayashi returned to Japan, via China, and married a 19-year-old girl (he was 34), a waitress at the Koyôkan restaurant (Koyama-Richard, 1997, p. 243; Kigi, 2009, p. 376). She would conduct his business in Tokyo while he continued to share his life in Paris with a certain Suzanne, known as "Madame Hayashi", from whom he would separate shortly thereafter, as she cheated on him in his absence with the printer Charles Gillot (1853-1903), according to Edmond de Goncourt (Journal des Goncourt, January 12, 1899; Koyama-Richard, 1997, p. 243).

The years 1890-1900 mark the height of Hayashi's career, but not necessarily of his financial success. During this time, American collectors fell in love with prints and sometimes paid very large sums for them. It was also a period when the price of Japanese art soared in auction rooms in Paris. It is estimated that in 11 years and 218 deliveries, Hayashi exported some 166,000 prints and 9,708 illustrated books (Emery, 2022 after Segi, 1980). However, the price of prints soon rose in Japan as well, which made it more difficult for the dealer to supply them, and led to lower profit margins (Koyama-Richard, 1997, p. 189; and 2001, p. 111).

The same year, Albert Bartholomé (1848-1928) made a bronze mask of Hayashi, which he probably knew from Edgar Degas (1834-1916), who owned a plaster copy (current location unknown). The bronzes are signed and dated 1892. A copy was exhibited in 1894 at the Salon de la Société nationale des Beaux-Arts, at Champ-de-Mars. A black bronze example is kept at the Musée de la Dentelle (the Museum of Lace) in Calais. Another is in a private collection in Paris, and another is kept in the museum of Takaoka. The copy in the Musée d'Orsay is in bronze with a red patina; it was acquired by the Société des amis du musée in 1990 (Paris, Musée d'Orsay, inv. RF 4303) (Koyama-Richard, 1997, p. 246).

In 1893, Hayashi was appointed curator of the Japanese pavilion at the Columbus Centennial Exhibition in Chicago. The group of twelve falcons on a perch, designed and financed by Hayashi and produced by the founder Suzuki Chôkichi (1848-1919), exhibited in Chicago, represents a financial failure for Hayashi, who failed to sell it. After being entrusted to the German collector Ernst Grosse, the work returned to Hayashi's widow. It is now kept at the National Museum of Modern Art in Tokyo (Kigi, 2009, p. 195; Koyama-Richard, 1998, p. 195). Hayashi returned to Paris in the company of Bing in the spring of 1894. In 1897, Hayashi participated in the publication Les affiches étrangères illustrées, for the Japanese section.

The Final Years

After 1897, Hayashi found himself faced with financial difficulties and sought to expand his business to other types of trade. He went to Russia to study potential oil deals (Koyama-Richard, 2002, p. 138-139). After the Exposition universelle of 1900, Hayashi was decorated as a Commandeur in the Légion d’honneur of France (decree of November 10, 1900) (Koyama-Richard, 1997, p. 199). In January 1902, after the death of his brother, Hagiwara, he closed his store and organised the sale of his holdings in Paris, during public sales in June 1902 and February 1903 (see sale catalogues).

In March 1905, he returned to Japan for good. He had an idea for a museum. He fell ill, then recovered. He died in Tokyo on April 10, 1906.

Hayashi's Legacy

Hayashi has long enjoyed greater notoriety in France than in Japan. The French decorations he received bestowed greater honours than those he received in Japan. In his country of origin, his action as a dealer remained controversial and his efforts to make Western art known to his fellow citizens were not crowned with success. He sincerely defended Japanese prints and the decorative arts of Japan, which were the main items, from the start, of the items he imported to France. The 1886 article in Le Paris illustré (whose cover illustration of a courtesan, reproduced from a print by Keisai Eisen [1790-1840], would be copied by Vincent Van Gogh) is strongly marked by the Western vision current in the era that placed great importance on the Ukiyo-e school and the decorative arts. The retrospective exhibition of 1900, including objects from the imperial collections, was undoubtedly a revelation for him as well; at least so he suggests in the lecture he gave on this occasion, in which he underlines the considerable progress made in the knowledge of ancient Japanese art (Hayashi, T., 1903). Akiko Mabuchi noted, however, that in the report of this lecture, 20 lines are devoted to the reign of Empress Jingû and 26 to that of Emperor Kuanmu, which belong to mythology, against 19 for the Fujiwara period and 11 only for the whole of the Tokugawa period (1603-1867), thus giving, without any historical foundation, a very large place to the imperial line, and almost none to the military aristocracy, in the history of Japanese art (Mabuchi, 2001, p. 43). His ardently patriotic speech underlines the original character of Japanese art, even when it imitates foreign models, and proclaims its superiority over the art of other Asian nations: Chinese, Koreans, and "Hindus". Hayashi's patriotism was also what seemed to characterise him in the eyes of his contemporaries, notably Koechlin (Koechlin, 1930). Hayashi indeed owed his career to the new imperial regime as well as to the opening of Japan; he defended his country and the new imperial regime; he was at the same time an admirer of Western modernity; he actively supported contemporary Japanese craftsmen and painters of the Western school of painting (yôga), and was irritated by Japan's slowness to reform. Despite his contributions, Hayashi was not a historian of Japanese art; he would come into conflict with the American art historian Ernest Fenollosa (1853-1906). His expertise is not without gaps either, if we consider the attributions of the objects kept at the MNAAG. On the other hand, Hayashi rubbed shoulders with or influenced the main collectors of Japanese art in Europe. He participated, especially through documentation and translations, in publications that had a very wide echo in France, such as Art japonais (1883) by Louis Gonse, as well as works by the Goncourt brothers Outamar o: Le Peintre des maisons vertes (1891) and Hokusai: l’art japonais du XVIIIe siècle (1883). These works would not have been possible without his help. He also rubbed shoulders with the most innovative artists of his time, in the West (Manet, Monet, and Pissarro, among others) as well as in Japan (Yamamoto Hôsui, Kuroda Seiki, and many others). Hayashi was not only one of the key players in Japonisme and one of the two great Japanese art dealers in Paris, along with Bing, but also an exemplary figure of Meiji's new Japan and its encounter with the rest of the world at the turn of the 19th and of the 20th centuries.

The Collection

Creation of Collections

Hayashi began collecting and selling Japanese works of art from his arrival in Paris until his death in 1906. The Asian collections were dispersed in Paris during public sales in Paris in 1902 and 1903. While the Japanese art collections mainly included prints and decorative art from the Edo period, with a small amount of older works, others, from the Imperial House, were acquired during the 1900 retrospective exhibition in Paris. Hayashi returned to Japan in March 1905 with 500 Impressionist works, according to some sources. This collection was put together first and foremost because the dealer agreed to accept works as partial payment for the Japanese objects or prints that were sold to artists, who did not always have great financial means (Takato-Hayashi, 2001, p. 89). In the same way, Hayashi would pay partly in Japanese works for the orders he placed, such as those for paintings for his house in Tokyo. He also had the idea of using this collection to promote Western art in Japan, by lending works for exhibitions or by organising exhibitions himself. Hayashi seems to have considered his collection to be incomplete and to have attributed an educational value to it for the attention of artists and the Japanese public. In 1890, he lent works by Charles-François Daubigny (1817-1878), Théodore Rousseau (1812-1867), and Jean-François Millet (1814-1875) to the exhibition of the Meiji bijutsu kai ("Association for the art of Meiji"). These exhibitions of Western art in Japan were not successful in their time, neither with the public nor with the Japanese press.

Asian Art Collections

While Hayashi's collections primarily included prints from the ukiyo-e school, they also included early Buddhist works. The sale from January 27 to February 1, 1902 included a painting of the bodhisattva Kshitigarbha (Jizô bosatsu) attributed to Kanaoka, Kamakura period, 13th-14th century, no. 1460, acquired by Grosse, as well as several old paintings now in the museum of Berlin. Also noteworthy is a painting of a pilgrim (catalogue, 1902, no. 1426, illustrated) which had been shown in the imperial pavilion in Paris in 1900 and which would be acquired by the Japanese collector Masuda Takashi (1848-1938). Masuda admired this painting, the illustration of which would also be published in the magazine Kokka. In the sale of February 16 to 21, 1903, there are also some ancient works, for example, a painting of the arhat Ashita, China, attributed to the Song dynasty, as well as ancient sculptures from Japan. Other important old works, put up for sale in 1902-1903, also entered French public collections, such as those acquired for the Louvre by the state or by the Amis du Louvre (in particular two Gigaku masks, EO 604 and 605) or still others, which were acquired and then bequeathed to the Louvre by Isaac de Camondo (1851-1911) or by Raymond Koechlin (1860-1931) (see below, documentation and archives of the MNAAG).

Western Art Collections

Among the exchanges of works enacted by Hayashi, we can note the exchange with Monet of several paintings for a large vase; with Degas, several drawings against a shunga album by Moronobu; with Raphaël Collin, prints by the painter against tsubas; with Pissarro, who gives him Baigneuse, le ruisseau. From the 1890s, Hayashi decided to expand his Western collection and bought works by Edouard Manet (1832-1883), Claude Monet (1840-1926), Alfred Sisley (1839-1899), Edgar Degas (1834-1917), Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919), Paul César Helleu (1859-1927), Camille Pissarro (1830-1903), Mary Cassatt (1844-1926), Berthe Morisot (1841-1895), Armand Guillaumin (1841-1927), Pierre Puvis de Chavanne (1824-1898), Odilon Redon (1840-1916), Paul Gauguin (1848-1903), Georges De Feure (1868-1943), Eugène Grasset (1845-1917), Eugène Delacroix (1798- 1863), Gustave Courbet (1819-1877), Théodore Rouseau (1812-1867), Camille Corot (1796-1875), Jean-François Millet (1814-1875), and Charles Daubigny (1817-1878) (Kigi, 2001, p. 17).

Apart from 197 drawings, as well as a painting by Renouard, which were bequeathed in accordance with his wishes to the Imperial Household Museum, the other collections were sold posthumously in 1908 in Tokyo. A large part of the collection was sold in New York in 1913. According to a descendant of Hayashi, Madame Yasuko Yuki, part of the collection was sold to support the family that was deprived of resources; the son of Hayashi is said to have squandered his father's fortune in the interwar period. Only a small number of works remained in Japan. There are works that belonged to Hayashi in the collection of the Bridgestone Museum, Tokyo (in particular by Camille Corot), Ville d'Avray, oil on canvas, around 1835-1840; or even by Eugène Delacroix, a watercolour, Étude de cheval, two works acquired in Paris by Hayashi in 1891 and 1892.

Hayashi's correspondence is kept at the Tokyo National Research Institute for Cultural Properties (Tôkyô kokuritsu bunkazai kenkyûjô). The BNF has a collection of letters from the Hayashi-Goncourt correspondence. The Musée d’Ennery owns part of Philippe Burty's correspondence and archives, which can be consulted in the library of the Musée national des arts asiatiques Guimet.

Related articles

Personne / personne