The Musée d’Ennery: Visualizing Nineteenth-Century Parisian Networks for the Circulation of East Asian Art

Le Musée d'Ennery: 59 avenue Foch, Paris

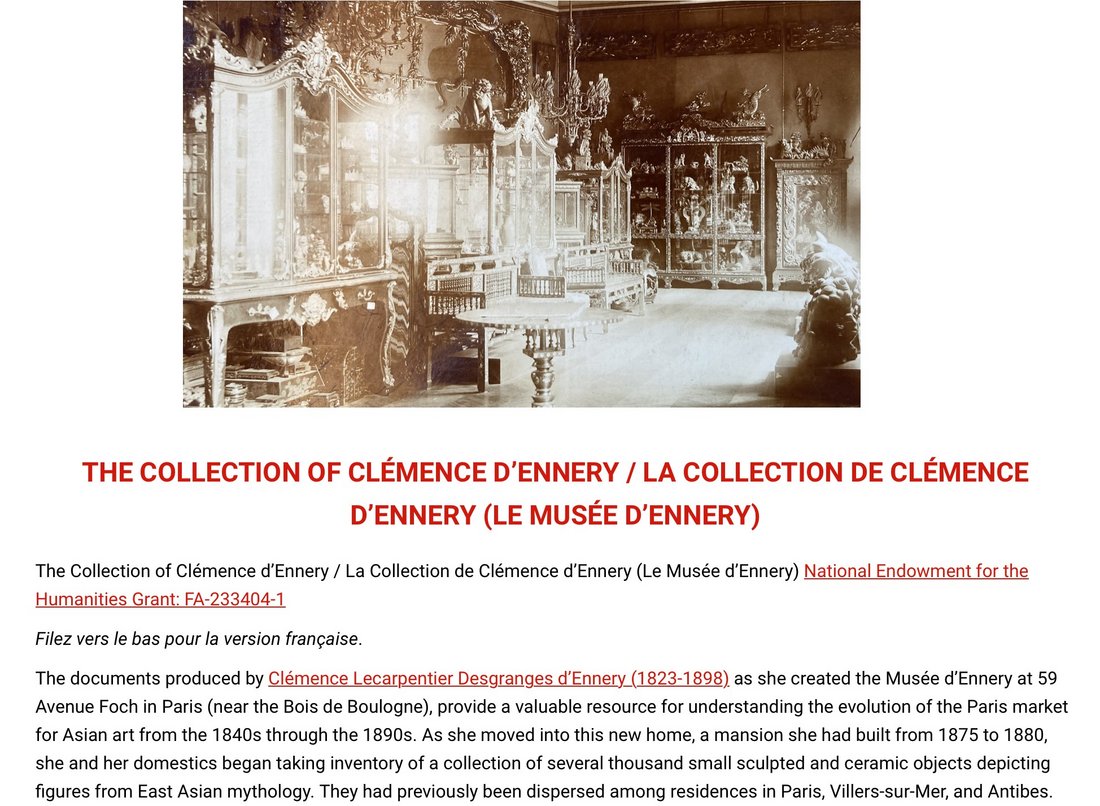

A veritable time capsule, The Musée d’Ennery in Paris preserves the late nineteenth-century passion for collecting and display traced in “Collectionneurs, collecteurs et marchands d'art asiatique en France 1700-1939,” a program launched by the INHA in 2022. The first French national museum of East Asian art with free admission to be designed by and bequeathed by a woman, Clémence Lecarpentier Desgranges d’Ennery (1823-1898) intended her collection, housed in a mansion at 59 Avenue Foch in Paris, to serve as a warm and intimate alternative to more “scientific” museums of her day. In addition to donating a collection of more than 6,300 small objects, including the opulent home in which they were displayed, d’Ennery added a generous 500,000-franc endowment to ensure that the museum admission would remain free to the public in perpetuity. She hoped that visitors to the Bois de Boulogne could stop in, examine the work of talented Chinese, Japanese and Korean artists, and learn more about the mythological figures and stories featured on the thousands of small sculpted and ceramic figures she had collected over a period of more than fifty years.

Today, this national treasure is administered by the Musée national des arts asiatiques—Guimet (MNAAG), which, faithful to d’Ennery’s bequest, has conserved the museum as it was when it first opened its doors in 1908. Like most time capsules, the museum’s objects, in conjunction with the lists Clémence d’Ennery made while designing the display spaces of her museum, provide valuable information that allows scholars to identify and map some 6,000 purchases made in Paris from more than 125 individual dealers during the 1840-1898 period. The “Collection of Clémence d’Ennery” project, directed by Elizabeth Emery and supported by a grant from the National Endowment of the Humanities, contains a transcription of her major inventory notebooks as well as a structured dataset listing brief descriptions of objects, the value she attached to them, and possible date ranges of objects sold by prominent art dealers S. Bing, Adolphe Worch, Florine Ebstein Langweil, Adolphe Chanton, Pohl et frères, Hayashi Tadamsa, Wakai Kensaburō, Nicolas Malinet, and many others.

data sets, and information about her networks.

Because most of these objects are still preserved in the Musée d’Ennery, this new open access source provides a rare opportunity for comparison. It invites assessment of the business practices of individual dealers and the quality of the goods they sold, including some of the first items exported to France by Japanese firms such as Mitsui, Kiritsu Kosho Kaisha, or Wakai and Hayashi who worked with them (see Figures 4 and 5 below). Even the works d’Ennery purchased from the 1840s until 1882 from unnamed sources (numbering around 1,400 of those recorded), reveal a great deal about the kinds and quality of works arriving in France at this time.

Mapping the Market

The interactive map below, drawn from the names mentioned by d’Ennery in her ledgers, allows one to visualize the neighborhoods she frequented (most are clustered in and around Drouot auction house or near the theater district where she grew up and spent much of her time as an adult). One can imagine her “making the rounds,” walking up a street and down another looking for new arrivals. Clicking on a shop icon in the map provides an estimation of the objects she recorded having purchased from each dealer, along with information about each business, triangulated from three databases (Agorha, Meiji Portraits, and Dat_Art Asie) and the pioneering thesis of Chantal Valluy and Lucie Prost. A click on the small box at top left of the screen provides information about the map; a full list of dealer names is provided at the bottom of the screen.

This map, based on d’Ennery’s own notes, reveal that she frequented the same dealers as better-known contemporaries including Philippe Burty, Emile Guimet, and Ernest Grandidier. Like Burty, Edmond and Jules de Goncourt, and Charles Gillot, she visited major importers like Bing, from whom she purchased nearly 600 objects, Adolphe Worch (nearly 500), Florine Langweil (nearly 400), and Adolphe Chanton (fourteen). But she also loved to hunt for bargains in small family-run antique shops and even department stores such as Le Bon Marché and the Grands Magasins du Louvre, which imported directly from the East Asia (Burty, Guimet, and Gillot also found treasures there). She would also purchase broken works or fragments, some given to her free from dealers, and incorporate them into the décor of her home.

Like Burty, Grandidier, and most other collectors of her generation (she was nearly a decade older than both of them), d’Ennery did not have the opportunity to travel abroad. It was a costly and physically grueling journey that only a few women undertook, generally when family members were stationed in embassies in Japan or China (like the Duchesse de Persigny in 1882; she was a decade younger). D’Ennery’s purchases, made entirely in France, capture the transitional moment when antiquities and souvenirs from China and Japan circulating in France from the Ancien Régime began to be complemented by new imports of antiquities provoked by political and military turmoil (the sack of Yuanming yuan; the forced opening of Japan, for example), and nineteenth-century decorative arts designed specifically for the European market.

The Collection of Clémence Lecarpentier Desgranges d’Ennery

In 1890s interviews with reporters, Clémence d’Ennery attributed her interest in small sculpted figures from the Far East to an adolescent passion (early 1840s): born into a wealthy family of rentiers of noble origin, she spent her pocket money on tiny beautifully crafted sculptures of animals and mythical beasts. Her father, Armand Lecarpentier de Saint Amand, served under Napoléon Bonaparte, and her great-grandfather on her mother’s side, Pierre-Jacques Cousteau de la Barrère, was a huissier ordinaire de la chambre du roi at Versailles. She inherited from her mother a number of antique vases, boxes, and small sculpted objects. Unlike her friends, who spent their time and money ordering dresses, she told reporters that she had chosen to invest in art, relishing the colors, material, and workmanship of figurines like Figure 8, one of her very first purchases: a “toad-tadpole” carved from a root that may have resembled a larger piece belonging to her mother. She often spoke to friends of her love for these small works that she could hold in her hand, asking them to appreciate their tactile qualities, craftsmanship, and creativity in using a variety of materials to represent different themes. She loved organizing them in different ways throughout her homes to bring attention to different aspects: color, shape, theme, material, type of work.

An article for the INHA “Collectionneurs” database provides extensive biographical details. Married in 1841 to Charles Desgranges, son of the mayor of the 11th arrondisssement of Paris, Clémence seems to have tired quickly of bourgeois married life. The couple legally separated in 1844 (divorce was not yet possible), and Charles took a position working in Algeria, thus allowing Clémence to control both her finances and her lifestyle. Much like writer George Sand, who gravitated to bohemian milieus in which her writing and witticisms were admired, Clémence Desgranges began co-signing plays with an up-and-coming playwright named Adolphe Philippe (“Dennery” and then “d’Ennery” were, at first, pseudonyms).

Clémence and Adolphe continued to collaborate in different ways throughout the rest of their lives, even if they could not marry until after the death of Charles Desgranges: Clémence worked to advance Adolphe’s career, she helped him craft the dialogue of his plays, and she served as hostess for the generous weekly dinners to which they invited friends and colleagues. The chart below provides a snapshot of the networks of friends, family, and art dealers Clémence named as having contributed to her collection from the 1840s until the 1890s through gifts, purchases, or trades. Their social networks were even more extensive.

D’Ennery’s gift-giving theater friends include members of the Félix family (Léa and Raphaël, siblings of famous actress “Rachel”), courtesan Jeanne Tourbay (future Comtesse de Loynes, one-time mistress of Adolphe’s collaborator, theater director Marc Fournier), and the Plunkett/Dalloz family (François Plunkett directed the Théâtre du Palais Royal; one of his sisters, Charlotte, acted under the pseudonym “Mme Doche” and another, Opera dancer Adeline, married Paul Dalloz, editor of the newspaper Le Moniteur). These networks of gifts suggest the extent to which the collection defined Clémence d’Ennery’s personality among her friends and acquaintances.

Clicking on an individual name on the map above reveals a brief description of the relationship between the friend, professional contact, or dealer, and gifts or items they sold or traded. It is important to note that these numbers may change as more documents become available: some are based on the count made by Valluy and Prost in 1975 and others from more comprehensive counts developed from additional notes left by d’Ennery that Valluy and Prost were not able to consult (Emery 2022). And yet, even approximate numbers provide a sense of the extent of involvement of particular figures in the construction of the museum. In the graph below, for example, it is clear that Clemenceau and Deshayes, who would help her shape the museum as of 1893, were among the friends who gave her the most gifts.

Others acquaintances who frequented the d’Ennerys’ weekly dinners and offered her gifts included Adolphe’s friends and theatrical collaborators, including playwrights Jules Brésil, Achille Collin, and other literary figures among then (as of 1858) two brothers who had begun to garner fame for their historical publications: Edmond and Jules de Goncourt. Fascinated by Clémence’s quick wit and willingness to buck convention, they equated her to an eighteenth-century courtesan in their Journal. This characterization has led to many of the misconceptions that persist about Clémence today. In fact, she was not an actress; she did not rely entirely on Adolphe for financial support, and she did not live with him in the early years. “Gisette” Desgranges may have adopted a libertine persona, but she came from a “bonne famille” (as she told them) and her presence in the stimulating demi-monde constituted by writers, actors, and artists was a choice, not a necessity.

Furthermore, numerous sources incorrectly state that the collection was Adolphe’s (friends regularly expressed surprise at how well he tolerated Clémence’s collecting “mania”), that he financed all of Clémence’s purchases, or that it was he who constructed the property at 59, avenue Foch. Notarial documents and receipts show that it was Clémence who purchased the land in 1875, built the house, and decorated it. The couple made this address their primary residence after their 1881 wedding, which transferred technical ownership of the house to Adolphe (wives were subordinate to husbands under nineteenth-century law). Because Clémence died before Adolphe, the final bequest was also in his name, even though it was her will (and her work) that laid out the parameters of the gift.

A Woman Collector

Clémence Lecarpentier Desgranges’ financial independence from 1844 to 1881 made it possible to establish the collection, whose evolution is traced in more depth in the book Reframing Japonisme, in an article for the INHA program, and in the “Collection of Clémence d’Ennery” site. Begun when she was a teenager (in the late 1830s or early 1840s) it grew over a period of more than fifty years. Jules de Goncourt, for example, was flabbergasted by this “bestiary” when he visited her apartment in 1859: it already contained some 150 of the small mythological figures found in the museum today, including Fig. 8 above and perhaps Fig. 9 below.

Both Jules and Edmond de Goncourt visited again two years later, when she had installed the collection in a small apartment above the Théâtre Saint Martin: as I have shown elsewhere, their essays on Japanese “monsters” were quite likely inspired by her collection (they had not yet actively begun their own collection of Japanese art). An 1861 exhibit at l’Hôtel Drouot further demonstrated the originality of her taste: journalists underscored the unusual and rare nature of the collection.

Thirty years later, the Ministry of Fine Arts encouraged d’Ennery to develop her collection into a stand-alone museum like the Musée Cernuschi (promised to the city of Paris in 1882, but only opened in September 1898). The result led to an expansion in acquisitions, thus profoundly transforming the scope of a collection first offered as rooms to be installed at the Musée Guimet or the Musée du Louvre (both of which already lacked space). Clémence’s initial collection, begun in the 1840s, was overwhelmed in the 1890s by the sheer volume of modern imports she was encouraged to add to increase the museum’s holdings (gifts and purchases by Clemenceau and Deshayes stemmed from this initiative). The many acquisitions of this period obscured the fact that she had once been in the avant-garde of French collectors of Far Eastern art.

Paradoxically, however, it is precisely the mixed quality of the collection that makes it so valuable for understanding the nineteenth-century circulation of East Asia art. A time capsule, it provides scholars with precious details about the objects sold by individual dealers during specific periods and a gauge of demand for these works based on prices and quality. The collection’s fifty-year time span captures different moments of the nineteenth-century interest in Chinese, Japanase and Korean art: works circulating in France since before the French Revolution; antique pieces imported in the 1860s; works produced specifically for European markets; and new nineteenth-century works (furnishings, installation, sculpture mounts and lamps) inspired by or incorporating fragments of East Asian craftsmanship.

The museum itself also constitutes a stunning work of nineteenth-century art. The house was commissioned from architect Joseph Olive and the decoration developed in consultation with d’Ennery’s longtime friends and partners, the artistic furniture makers Jean-Paul Mazaroz and Gabriel Viardot. Mazaroz was responsible for the initial installation of the home, mantelpiece, and furnishings at 59 avenue du Bois de Boulogne (now Ave. Foch) in the period from 1877 until the company’s liquidation in 1890. D’Ennery had partnered with Viardot since well before 1882. A furniture maker, but also a sculptor specialized in fantastic wooden objects, Viardot worked as her agent, buying objects from other dealers, making stands and sculpture mounts for her, repurposing fragments she salvaged from dealers, repairing broken objects, finding and selling her objects, and offering her gifts.

D’Ennery’s inventory allows us to identify a huge number of stands and statue mounts that were crafted by Viardot and bronze specialist Eugène Hazart, often from scraps or repurposed materials. Once the childless Clémence d’Ennery had decided to “marry her daughter” (the collection) to the French nation (this needed the approval of Adolphe, who inscribed her bequest into his own will), she expanded the gallery space to house the new acquisitions. With Viardot, Clemenceau, and Deshayes, designated as future curator of the Musée d’Ennery, she designed the opulent final display spaces of the Musée d’Ennery, including the seat cushion embroideries she made herself (inspired by Indian fabrics) visible in Fig. 10 alongside Viardot’s vitrines.

Opening the Time Capsule

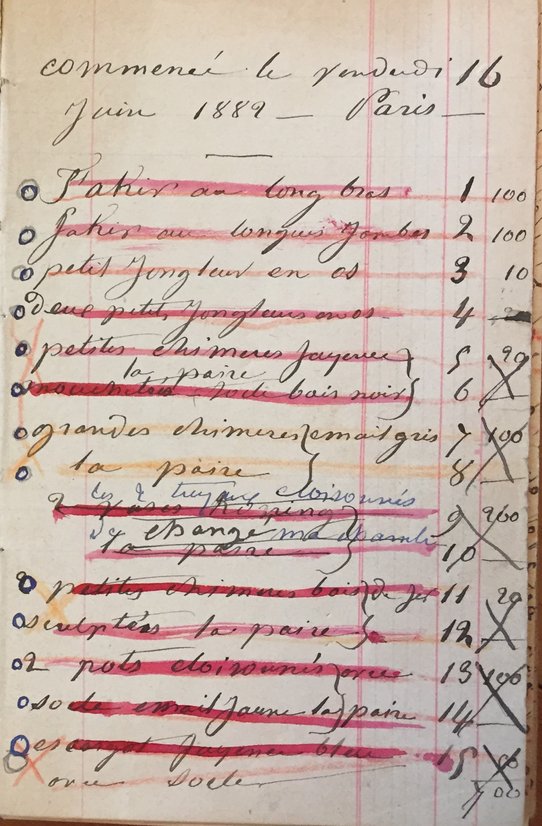

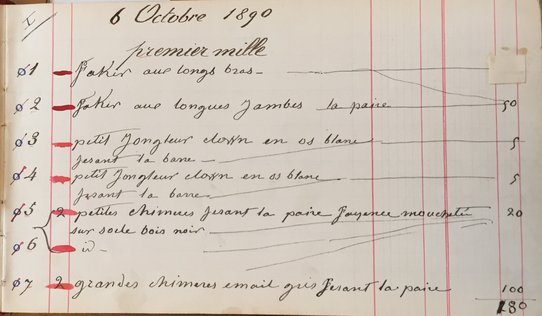

How do we know so much about Clémence d’Ennery’s networks and dedication to museum design? Because curators preserved the extensive notes she left about the objects and where and how she intended them to displayed. She began an inventory (she called it a “recensement”) in 1882, with the help of her domestic staff. They located, transported, and organized several thousand objects spread among residences in Paris, Villers-sur-Mer, and Antibes. She then added new purchases as she made them, along with periodic indications related to the dates when she stopped and restarted her notes. Photographs and details about these handwritten ledgers and the choices made in transcribing them can be consulted here. They provide valuable details about her relationship to different dealers, as well as her appreciation of the objects purchased. While an inventory rather than a technical appraisal of individual pieces, she clearly distinguishes between rare objects (acquired from antiquities dealers or from family members and friends) and “modern,” “common,” or broken objects that she bought because of their visual interest, craftsmanship, or because they were less expensive if sold as part of a group.

Fig. 11 provides a sense of the utilitarian nature of this project: the verification marks make the notebook nearly illegible. The master color-coded ledger into which the information from Fig. 11 was later transcribed (Fig. 12) contains references to lost numbers (“numéro manque”), to missing objects (“perdu”), to objects that initially escaped numbering, or to numbers to which labels had fallen off and were later renumbered (“annulé”). Some have been lost in transit, others stolen by employees, others unable to found (or later found!). If d’Ennery had lived to finish her inventory, which poignantly ends with a long list of unfilled numbers, she might have produced a final, cleaner copy.

When examining the data related to number of objects sold or given by the members of Clémence d’Ennery’s networks, it is thus important to keep in mind their context and function which complicates the counting of names and numbers. To give just one example, she often lists a salesperson’s name (like Hayashi, Bing, Worch, or “Mr Ibrahim”); all were involved with different stores over the years. In the absence of more specific detail, I have respected d’Ennery’s tendency to attribute objects to a person rather than a store, but this also means that the total number per store may be much higher than suggested by the charts. There are also duplicates in her records (the labels she affixed kept falling off and she had to renumber them), but it is not always possible to tell whether the entry is a duplicate or a similar object. The graphs presented here seek to identify trends rather than to provide definitive numbers. The Ledgers of Clémence d’Ennery (Le Musée d’Ennery), Part I project contains much more information about methods, data collection, and rationale behind interpretation of this data. The charts here, drawn from The Ledgers of Clémence d’Ennery (Le Musée d’Ennery), Part 2, are intended to provide a sense of how even rough data about d’Ennery’s networks of friends and dealers help understand the market for Far Eastern art from 1840-1898.

The use of names rather than stores proves even more problematic for women, because nineteenth-century social conventions did not always recognize their work (“Mlle Marie,” the daughter of Henri Ibrahim, was identified from a receipt). Married women are more easily traced than daughters (“Madame Desoye,” “Madame Doucet,” “Madame Guérin,” “Madame Winternitz,” “Madame Hatty,” and “Madame Langweil,” among others), but some, like “Madame Méault” or “Madame Nanty,” perhaps employees in larger stores, remain elusive. Nonetheless, the many references to women in d’Ennery’s networks provide valuable insights into the active presence of women in the East Asian art trade. At a time when legal documentation tended to list working married women as having “no profession,” d’Ennery provides valuable proof of their contributions alongside other family members.

D’Ennery’s ledgers provide an abundance of detail about the collecting practices of an independent woman whose taste remained largely constant over a period of fifty years: she loved small sculpted and ceramic representations of mythological creatures and sought out bargains throughout Paris. Above all, she wanted to share these treasures with the world. Clémence d’Ennery’s work with the Ministry of Fine Arts to transform her private home into a “warm” and inviting museum that would be free and open to the public explains why figures like Gustave Geoffroy, who argued for the importance of evening hours for the working classes (what we now call “nocturnes”), praised d’Ennery’s installation in the press. Like Emile Guimet and Henri Cernuschi, she wanted others to appreciate the remarkable technical dexterity, variety of materials, and variations on mythological themes that characterized the East Asian decorative works arriving in France during the nineteenth century. Thanks to her generosity, a visit to the Musée d’Ennery allows visitors to rediscover objects that passed through the hands of an extraordinary number of the figures chronicled in the INHA program “Collectionneurs, collecteurs et marchands d'art asiatique en France 1700-1939.”

Acknowledgments: Pauline d’Abrigeon, Lucie Baumel, Antoine Chatelain, Cristina Cramerotti, Peter Emero, Emeline Frix, Michèle Galdemar, Pauline Guyot, Melanie Hawthorne, Kazuko Akimichi, Jade Norindr, Chloé Pochon, Léa Ponchel, Juliette Trey, Nolwenn Voleon, the Documentation Department of the Musée national d'art asiatique - Guimet, The National Endowment for the Humanities.

Further information : Fascinant Extrême-Orient ! Déambulation au musée d’Ennery [Fascinating Far East! A stroll through the Ennery museum], podcast in French.

Notices liées

Personne / personne

Collection / collection d'une personne