ROCHLITZ Gustav (EN)

Gustav Theodor Rochlitz, born 2 April 1889 in Bromberg (now Bydgoszcz in Poland) in the Prussian province of Posen (Poznań in Polish) was a German art dealer active from 1921–1972. He became very wealthy during the Occupation, particularly through numerous exchanges of peintings with the Nazi spoliation services.

Years of training and establishment in Paris

In 1908 at the age of 19, Gustav Rochlitz went to Berlin to study scenic and easel painting for three years, after which he worked as an independent painter until 1914. Due to poor health he was unfit for active duty during World War I and was assigned to auxiliary services. In 1917, he was sent to Brussels and to Ghent, where he worked as an illustrator for a German newspaper published in Belgium.1 He claimed to have been encouraged to become an art dealer by the celebrated director of Berlin museums, Welhelm von Bode, whom he met shortly after the end of the war. In 1921 he began to trade in art on a small scale and travel throughout Europe to buy paintings, mainly in Italy and Holland.

From 1924 to 1930, he had his own gallery in Berlin, at 1 Friedrichstraße, though beginning in 1925 he spent most of his time outside Germany, that same year entering his first professional association with the Weder gallery in Lucerne, Switzerland, which lasted until 1928. A partnership in Zurich with Dr Stoeri was engaged soon after, and an association with the van Diemen gallery in Berlin, directed notably by Dr Eduard Plietzsch (1886–1961). When the Stoeri gallery went bankrupt in 1931, Gustav Rochlitz evaluated his losses at 260,000 Swiss francs.2 He then opened the Muralto gallery in Zurich, which he managed for a Swiss banker, Guhl, and in 1932 organized there an exhibition of old masters well received by the press. However, the Swiss authorities refused him the right to officially administer a business in Switzerland, a priori due to his German nationality. According to Rochlitz, the success of the exhibition earned him the enmity of Theodor Fischer (1878–1957), an art dealer in Lucerne, who convinced the Swiss government to exclude him from the professional corps for reasons of “unfair competition.”3 Nonetheless, it is worth mentioning that the two dealers did business together from 1925 to 1927.4 According to reports concerning Rochlitz established in 1946, Rochlitz may have had to leave Germany in 1925, then Switzerland in 1932 due to dubious business practices.5

In 1933 Rochlitz therefore left Switzerland for Paris, where he opened a gallery in his name (registered on 24 March 19346). First in the cité Bergère in the Faubourg–Montmartre neighborhood, near rue Drouot, in 1936 he moved to 222 rue de Rivoli. He traveled less, concentrating on Belgium and Holland, with an occasional visit to Italy. On 1 August 1937, he created the SARL (Limited Liability Company) “Établissement Rochlitz” composed of Gustav Rochlitz, Wally Hackebusch, his second wife, and Édouard Weil, his accountant, who lived rue du Faubourg-Poissonnière. Between 1933–1940, Édouard Weil received from 2% to 3% of the company’s net profits, but disappeared in 1940. Rochlitz mentions having tried in vain to contact him and assumed that being Jewish, Weil had gone into hiding to escape anti-Semitic persecutions. The company was dissolved on 31 January 1941 and business was managed solely by Gustav Rochlitz until 24 April 1944, when it again became a SARL, composed of Rochlitz and Henriette Papazian (1900-1946), née Breton, who lived 12 villa Poirier in the 15th arrondissement.

Already before the war, Gustav Rochilitz had among his main supporters and friends a number of personalities in the French art world, such as Édouard Mortier, duc de Trévise (1883-1946) and the museum curators Hans Haug (1890-1965) and René Huyghe (1906–1997). He was also close to the art dealer Ernest Ascher (1888-c. 1953), established rue Jacques-Callot, the German painter and collector Richard Goetz (1874-1954), and he carried on professional relations over a long period of time with well-known figures of the Dutch art market, such as the antiques dealer Piet de Boer (1894-1974) and the art dealers D. A. Hoogendijk and Katz.7 According to a report of the Vaucher commission, Rochlitz’ connections with the French and European art market since before the war allowed him to inquire about Jewish collections in view of future requisitions.8 He asserted, however, that he came to France as a refugee and victim of political persecutions, although his second wife, whom he married in 1936, his associate and Berlin-born mistress Wally Hackebusch, “did nothing to hide her fierce pro-Hitler feelings.”9 The couple’s application for French naturalization was interrupted by the outbreak of the war. A few months previously, Rochlitz did obtain French nationality for his daughter, Sylvia, born in 1934.

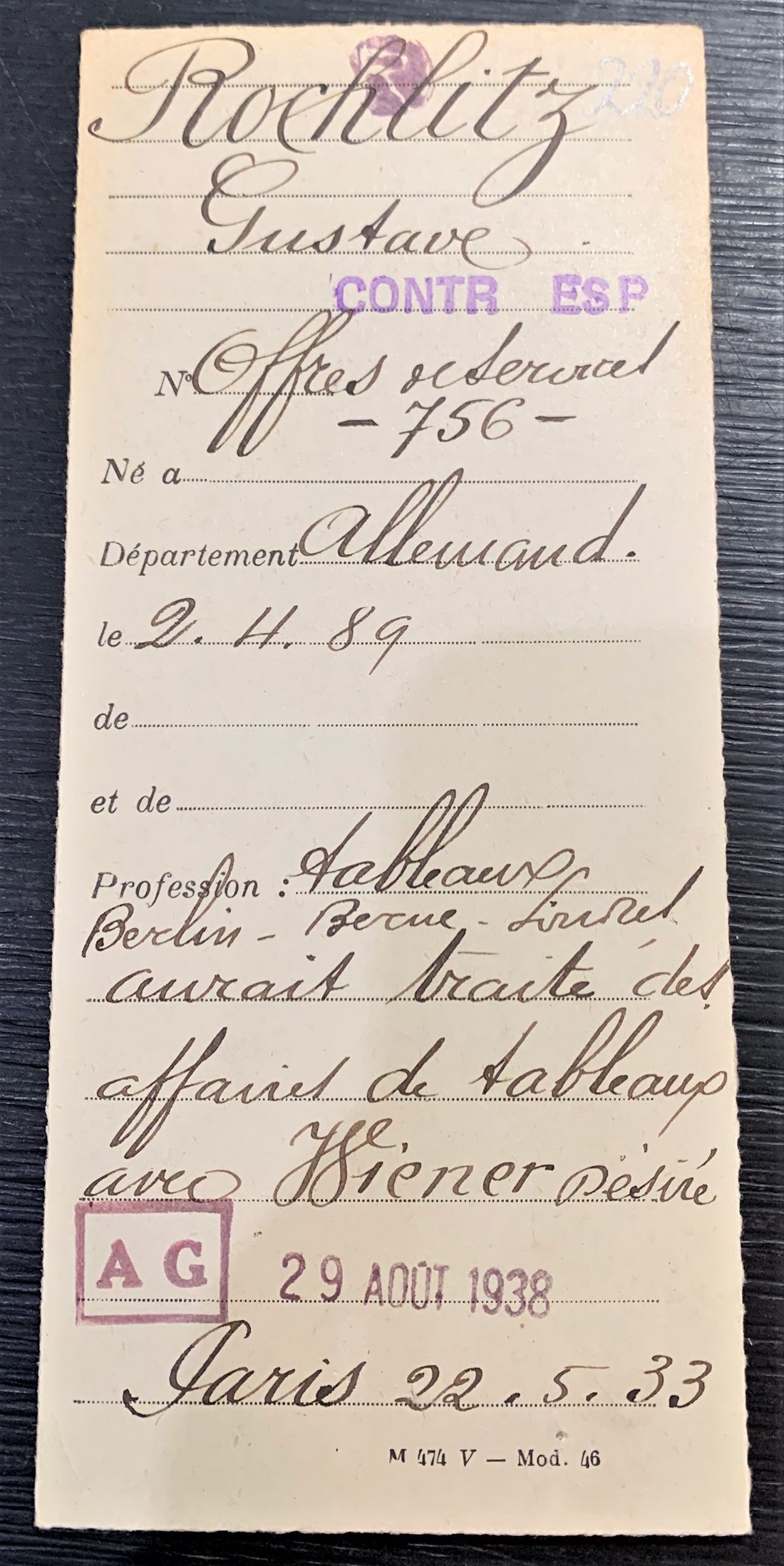

Source : Archives nationales, Ministère de l’Intérieur, Direction générale de la Sûreté nationale (fonds de Moscou), Fichier Central, 19940508/1795.

First sales at the outset of WWII

When France entered the war in September 1939, Gustav Rochlitz, considered a “national of enemy powers”1 was interned by the French government in the Colombes camp (Hauts-de-Seine), set up in the Yves-du-Manoir stadium. Thanks to his daughter’s French nationality, he was released after three weeks. Fear of a German fifth column found him in another camp in April 1940, in Bassens (Gironde). On 20 June 1940, after the German entry into Paris, Rochlitz was liberated by the NSDAP-Auslandsorganisation (NSDAP/A0, Nazi Workers Party). During is internment, his possessions were divided between a bank vault2 and his residence rue de Rivoli, where he lived from November to December 1940. Gustav Rochlitz said he had been told by friends at the time, that numerous German officials, art dealers and museum functionaries were buying massively on the Parisian art market, and that he had been advised “not to go into hiding,” but to re-open his business to take advantage of the favorable situation. On that point, he declared in June 1946: “during the Occupation, I would have preferred not to make a single sale, I went into hiding for several months, but I couldn’t remain hidden all the time.”3 After a relatively short period of inactivity, he re-opened his gallery in November 1940 and began selling to Germans on a large scale. His first transaction was arranged through the intermediary of the painter and dealer Adolf Wuester (1888–1972), acting for Dr Hans Wilhelm Hupp (1896–1943), director of the Düsseldorf Kunstmuseum, whom Rochlitz had known in Germany.4 Wuester received 20 % net profit on the sale of two 17th c. small Dutch masters.5

At the same time, Rochlitz sold an Annonciation,6 attributed to Maître de Messkirch by Karl Haberstock (1878–1956), Berlin art dealer particularly well introduced in top Nazi circles, accompanied by Dr Hans Posse (1879–1942). During those first months of activity, Rochlitz also did business with Maria Almas-Dietrich (1892–1971) from Munich, introduced to him by Wuester,7 as well as with Dr Franz Rademacher of the Rheinisches Landesmuseum in Bonn.8 Adolf Wuester may have been involved in these transactions.9 Rochlitz also sold to Alsatian institutions that became German, such as the Beaux-Arts museum of Strasburg, in the person of Dr Kurt Martin (1899–1975), who in 1941 acquired a canvas representing seven dignitaries of the church by a Master of drapery studies.10

Exchanges at the Jeu de Paume and prospection on the French art market

In February of the same year, Rochlitz was visited by Dr Bruno Lohse (1911–2007), member of the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg and acting for Hermann Göring. Lohse told him that Göring would soon be in Paris and asked if he had any exceptional paintings to sell him. Rochlitz proposed a Portrait d’homme attributed to Titian1 and a large Nature morte by Jan Weenix. Lohse transported them to the Jeu de Paume museum to include them in the exhibition for Göring. Eight or ten days later, Lohse returned and told Rochlitz that Göring refused the two painting because the price was excessive, but would consider acquiring them for an exchange. According to Rochlitz, Lohse warned him that he had no choice but to accept, otherwise he would have to “assume the consequences.” The transaction was thus made, and the two paintings were exchanged for eleven 19th and 20th c. French paintings,2 making it the first exchange of “degenerate art” for old masters.3

Besides Bruno Lohse, the German art dealer Hans Bammann, a particularly active buyer in France for museums in Düsseldorf, Cologne, Aachen and Bonn, was one of Rochlitz’ priority contacts in the ERR. However, most of his affairs with the ERR were negotiated by Lohse. Rochlitz, who never met Göring personally, said he was only in contact once or twice with the person in charge of his personal collection, Walter Andreas Hofer (1893-c. 1971).4 Just the same, those few contacts allowed him to operate eighteen artistic exchanges with the ERR between 3 March 1941 and 27 November 1942, during which he received 82 confiscated paintings5 for about 35 paintings, perhaps more.6

Thanks to that apparently inexhaustible supply of looted works, Gustav Rochlitz was able to increase his transactions on the French art market. Among his clients were a number of colleagues or brokers, such as Alfred Klein, Mlle Levy, Yves Perdoux, Raphaël Gérard, Paul Cailleux, Pierre Landry, Paul Pétridès – who bought from him several paintings from the Paul Rosenberg collection – Ignacy Rosner, Jean-Paul Duthey – with whom Rochlitz exchanged a portrait of Goya from the John Jaffé collection – Hildebrand Gurlitt, buyer for the Dresden and Hamburg museums,7 and the artist Lucien Adrion, known for having worked with the Parisian Propagandastaffel. Rochlitz also had connections with the Dienststelle Mühlmann (Mühlmann Service) via the art historians Josef Mühlmann and Eduard Plietzsch.8 He was also close to count Alexandre von Frey, a Hungarian citizen living in Lucerne, who also engaged in artistic exchanges with Lohse from Switzerland.

As of 1941, Lohse obtained for Rochlitz a laissez-passer from Göring authorizing unlimited interzone movements, in exchange for which Rochlitz gave Göring first choice among the works acquired in the free zone. Rochlitz thus made about ten trips between Paris and the Côte d’Azur from 1941-1943, buying works from Thierry, an art dealer active in Paris and Nice, and renewing contact with Wiesner, a Czech intermediary “well-known” to the German buyers on the Côte d’Azur that he had met before the war.9 In Nice, he occasionally encountered dealers who were refugees, like the Hungarian Jew Sandor Donáth, the Spaniard Paolo Aflallo de Aguilar and the German Ward Holzapfel10. His artistic prospecting extended to Montpellier, and Rochlitz often corresponded with Haberstock to inform him of his discoveries.11

Named colonel at the Nice Kommandatur in 1944, Rochlitz was also active in the region on behalf of his Jewish colleagues about whom he claimed to be concerned: in fact it seems that his relations with Bruno Lohse allowed him to be informed of the massive arrests of Jews planned for the summer of 1944.12 Thus we note that Rochlitz, like Wendland, was a friend of the wife of the art historian August L. Mayer (1885–1944), who lived in Nice, then in Monte-Carlo during the war, before being arrested.13 Several times, Rochlitz transmitted to Mayer letters from his wife, who remained in Paris. In 1942, August L. Mayer had also introduced Rochlitz to Jean Dutey, a paintings expert established in Paris at 9, rue Crevaux, with whom he became friends.14 After the war, Jean Dutey testified during the trial of Rochlitz, assuring the public of his “violently anti-Nazi sentiments.”15

Links with the ERR

The confiscated paintings that Rochlitz acquired from the ERR were sold to other art market professionals, in France as well as Switzerland and Germany, thanks to the Parisian branch of the transport firm Kühne & Nagel.1 When Rochlitz was told after the war where the works he had exchanged came from, he declared “those dealers knew the origin of the paintings I sold them – in Paris, anyone having anything to do with paintings knew they were looted art works.”2

By selling to officials and high-ranking Nazis, Rochlitz also intended to position himself as a top-level actor in the German artistic circles in Paris, entertaining his guests “sumptuously”3 in his living quarters rue de Rivoli. The results of such behavior were not long in coming, for as of 16 March 1941, baron Kurt von Behr (1890-1945), head of the French branch of the ERR, attested to Rochlitz’ excellent work both for the organization and on behalf of the Reichsmarschall, and ordered that whatever was needed to facilitate the pursuit of his mission be put at his disposal.4

Interrogated after the war, Rochlitz tried to minimize his participation, declaring that it was despite himself that he had taken part in the commerce of looted art, presenting himself as a fierce opponent to the Nazi regime, hoping to become a French citizen. To clear himself, he also reported that Bruno Lohse and Robert Scholz “often spoke in almost hysterical terms of the ‘degenerate’ nature of modern French art,’5 which under no pretext could be brought to Germany and would be burned rather than returned to their owners. Rochlitz invoked the “safeguard” of modern art argument, stating that he always felt “that one day, he would find an arrangement with the legitimate owners of the confiscated paintings and return them.6

Those allegations were however discredited by Lohse and Scholz, who agreed, when interrogated after the war, that Rochlitz had engaged in dealings of his own free will and had even sought out transactions with the ERR. It was a business that allowed him to make spectacular profits, since exchanges were largely in his favor, given art market standards on the international scale. More than once, in exchange for a single painting he would get ten others, any one of which was of a higher value than the one he had given up.

Moreover, the works he came to own in this way included a number of masterpieces of French 19th c. painting that would have cost ten times more in times of peace, and that he obtained in exchange for “old masters” of questionable quality, but more sought after due to Nazi artistic policy. He visited the Jeu de Paume regularly, chose the paintings he wanted to exchange, which were sometimes delivered directly to his home or office.7

Capitalizing on his knowledge of the French art market, as well as on Nazi greed and ideology, Gustav Rochlitz was considered “one of the most ubiquitous and malodorous of the Nazi art agents” in the art market.8

Postwar legal proceedings

During the Occupation, Gustav Rochlitz profited personally and materially from ERR plundering: one of his bank accounts showed the sum of 80,000 F when he opened it in April 1940, 661,000 F the following year, and 4,056,000 F in 1943. In four years, the amount was estimated at 5,685,000 F by the Comité de confiscation des profits illicites, which added:

All the testimonies of people who had anything to do with Rochlitz […] are in agreement that the German was well positioned to carry out important transactions with numerous dealers and art lovers on the other side of the Rhine and that he took advantage of the facilities and protection granted him after the events of June 1940, both by the German Occupation authorities and by the Vichy government. His lifestyle shows he could do as he wished. Indeed, just after returning from exile [he abandoned] the 3 or 4 rooms of the apartment at 222 rue de Rivoli, used it only for business [and] moved to a 7-room hôtel particulier in Passy at 15 rue Vineuse, rented at 16,000 F, and that he decorated according to his taste, with the appropriate antique furniture and curios. Considering the price of these various items, the cost could easily be estimated at 1,000,000 francs.1

Taking into account the favorable context in which the transactions were made, Rochlitz could not have made less than a 50% profit net on sales, or 2,342,500 F2 net from 1941 to 1944. A considerable amount, when compared to his income before the war, as he declared it: “I can’t give you an exact figure for my income, but I had 30 – 40,000 francs profit each year. I mainly sold paintings I had bought.”3

Besides the considerable financial benefits, Rochlitz figured that his exchanges with high-ranking officials in the Nazi hierarchy would allow him to avoid his military obligations. He believed that Göring’s accreditation could serve that purpose, and it was with that in mind that in March 1944 he asked Dr Hermann Voss, director of the Linz Führermuseum,4 for a certificate attesting to his commercial activity with German officials. From that point of view, the Allies who interrogated him in 1945 had “the impression of a weak and cowardly person. Several sources indicating an addiction to morphine have turned out to be true. Politically, Rochlitz has no authentic convictions. Each time, he acted in his own interest, as an opportunist with no scruples.”5

In the end, the certificates signed by Göring and de Voss didn’t have the expected effect and Rochlitz was called up for military duty in Paris on 14 July 1944. He did a two-week training period in Sicherungs-Regiment 1 (Volkssturm militia for the defense of Paris), after which he obtained a medical dispense on 16 August 1944 and left Paris on 20 August 1944, having sent all the artworks remaining at his home rue Vineuse to Switzerland, and joined his wife and daughter in Hohenschwangau (Füssen), on the Austro-Bavarian border, its château used as a repository by the ERR. The majority of his acquisitions were then in Germany, and divided between Hohenschwangau (Füssen), Aufhofen (Egling, Bavière), Mühlhofen6 and Ravensburg7 (on the Lake of Constance, in Bade-Wurtemberg), Lörrach,8 Fribourg, with Schaffer & Co, and the château of Adolfsburg9 (in Oberhundem, in North Rhine Westphalia). From Füssen, Rochlitz occasionally traveled to Baden-Baden and Fribourg to set up business. Beginning in June 1943, he rented an apartment for himself and his family in Baden-Baden at the home of a Mme Jordan, at 5, Wilhelmstraße – a place he also used to stock artworks.

On that subject, it is important to note the number of depots used by Gustav Rochlitz, between France, Switzerland and Germany. During the war, he even shared one with Maria Almas-Dietrich in Oberammergau (Upper Bavaria), from where he evacuated by mistake a medieval sculpture belonging to Dietrich.10 This sculpture was previously in the collection of Harry Fuld (1879-1932) and Dietrich acquired it from Hans W. Lange at the sale of the Fuld collection between January 27th and 29th 194311. Repatriated to France after the war, the work is still part of the National Museums' recovery assigned to the Louvre12. These multiple depots illustrate how Rochlitz distributed, then redistributed in Germany the artworks acquired in France with the aid of a network of local agents, most of them still little known. The scattering of his collection in different places doubtless allowed him after the war to cover up his tracks and hide the existence of certain depots; in that sense, the information supplied by the ALIU reports (Art Looting Investigation Unit) is not conclusive, since certain artworks declared lost by Rochlitz during transfers via Baden-Baden, in reality resurfaced during the discovery of the Lörrach depot in 1949.13

At the Liberation, seals were placed on 222 rue de Rivoli, where there remained a few paintings and a large number of frames.13 Rochlitz fled in August 1944 to Germany where he was arrested on December 13. During the period from July 15th to August 1st, 194514, he was interrogated by the American army in a special interrogation center in Austria. While imprisoned in Germany, three decisions concerning him were made by the 2nd Comité de confiscations des profits illicites de la Seine, which ordered the overall sequestration of his property15 and several financial confiscations accompanied by fines, each fixed at the maximum laid down by the law. In all, the accumulated confiscations and penalties amounted to 13,420,000 F.16 Transferred to the French authorities between end 1945 and beginning of 1946, Rochlitz was then interned with other collaborators in a guarded center in Sorgues, in the Vaucluse department. Interrogated by examining judge Marcel Frapier on 6 January 1946 in Paris, he was detained in the prison of Fresnes, charged and brought to court, then sentenced on 28 March 1947 by the Seine Court of Justice to three years imprisonment, 60,000 F fine, lifelong indignité nationale (forfeiture of civil rights) and the general confiscation of his possessions for economic collaboration.17 He is thus one of the few Germans to be tried before the Court of Justice of the Seine. As of 1946, the Art Looting Investigation Unit of the OSS (Office of Strategic Services) put him on its list of “Red Flag Names” his exchanges with the ERR being cited at the Nuremberg trials to describe the extent and variety of the forms of artistic spoliations.18 Reputed to be “one of the most notoriously crooked German art dealers”19 to have compromised himself with the ERR, Rochlitz is among the persons most severely sanctioned by the French courts at the Liberation.

Rochlitz left the Fresnes prison on 10 July 1948.20 By decree of 22 November 1950, the president of the Republic granted him a remission of the penalty of lifelong indignité and general confiscation. Rochlitz then sought to recuperate his possessions and, with the petition dated 20 January 1956, requested the revision of the decisions of the Comité de confiscation des profits illicites de la Seine. Considered admissible by law, his request was rejected on the basis of principle and payment of the financial penalty was confirmed.21 He continued his activity as an art dealer in Füssen and Cologne until his death in 1972, at the age of 83.22