Museums as actors in the French art market during the German Occupation

The dynamic development of the French art market during the German Occupation is not due solely to the collecting frenzy of the higher-ranking officials of the Nazi regime—first and foremost Hitler’s for his planned ‘Führermuseum’ in Linz1 and Göring’s for his estate, Carinhall.2 Many museums also made use of the possibilities opened up to them by the conditions under the Occupation to make extensive art acquisitions and to enrich their collections.3

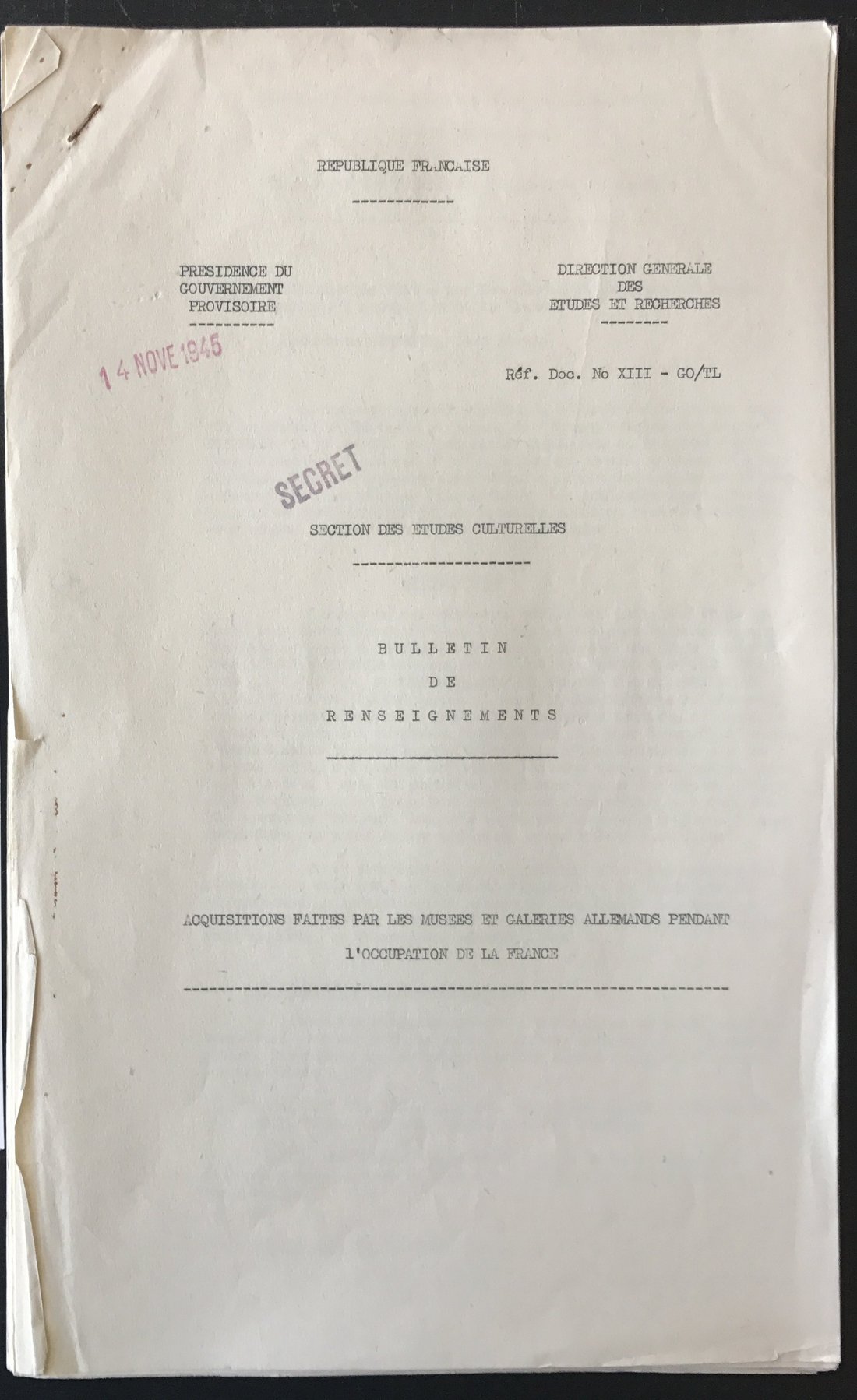

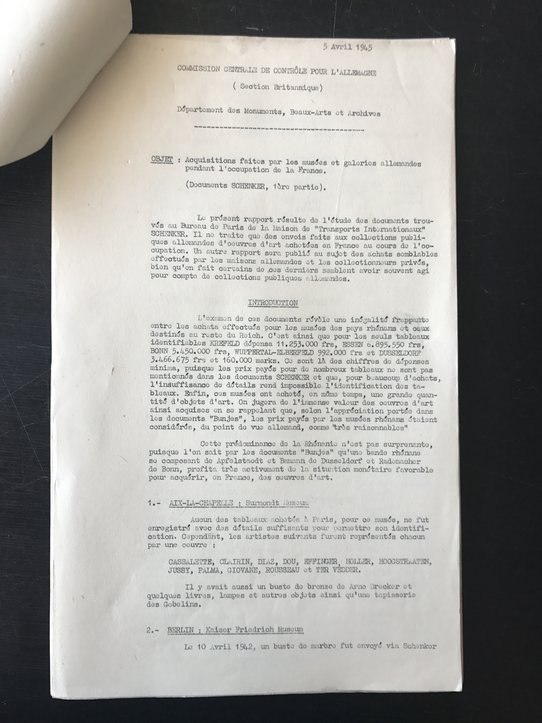

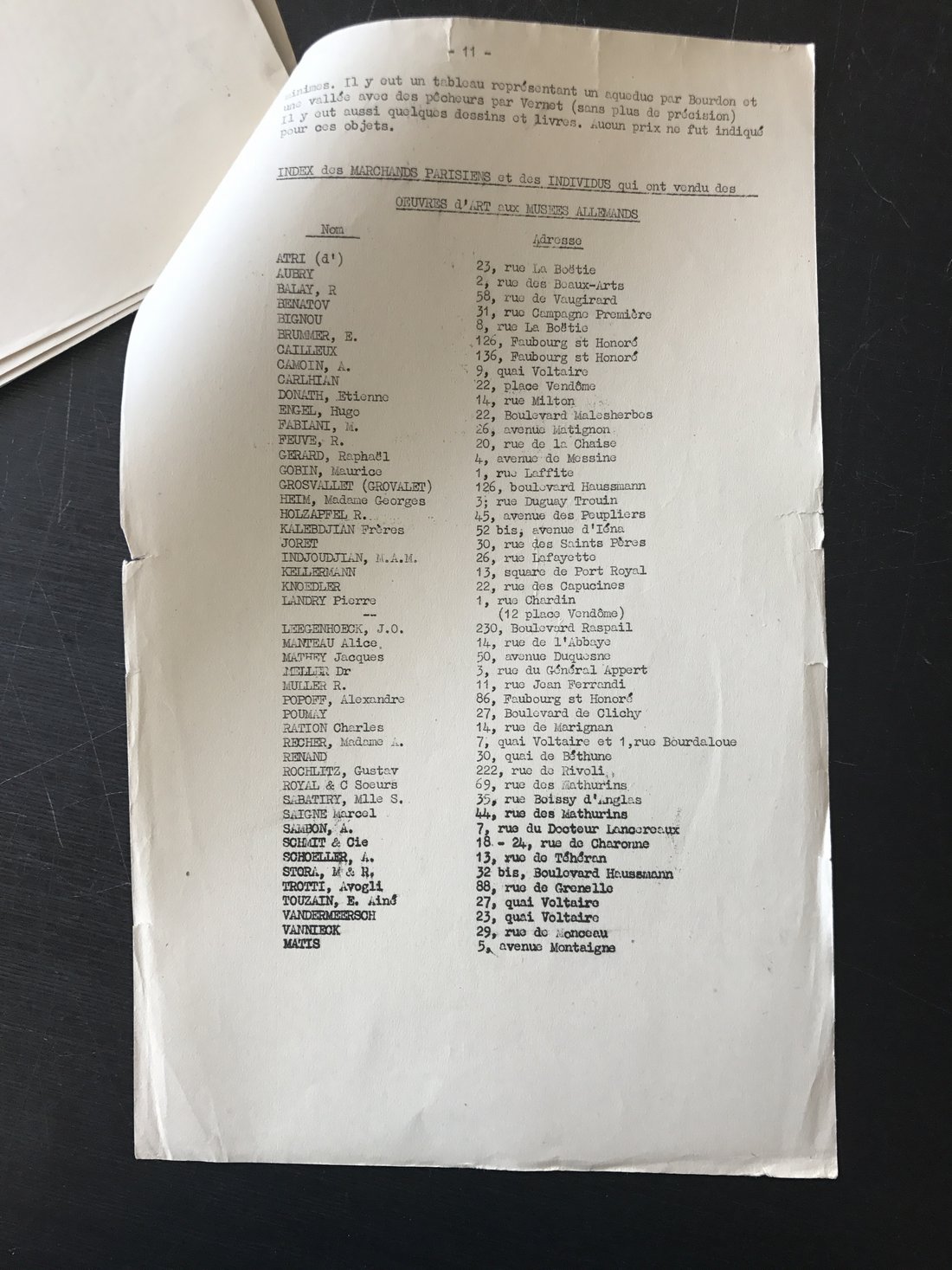

The 1945 report, ‘Accessions to German Museums, and Galleries during the Occupation of France—The Schenker Papers’,4 remains the most important source concerning the activities of German museums in Occupied France.5 Based on the analysis of commercial documents confiscated from the transport firm Schenker in Paris, the Schenker papers' list countless acquisitions by German museums. Yet the true extent of these acquisitions only became apparent from post-war investigations conducted by the cultural heritage protection officers of the American, French and British Occupying Powers, who also examined the holdings of German museums transferred during the war at the Collecting Points. Accordingly, the French cultural heritage protection officer Rose Valland established for instance that ‘the emissaries despatched to France by the city of Cologne waged a real campaign to make acquisitions of various kinds’.6

Neither provincial museums, such as in Celle,7 nor the houses of large cities such as Hamburg8 or Nuremberg,9 had failed to take advantage of the Occupation for art acquisitions during the war and they acquired objects of various genres, regions and eras. Yet it can be established that the museums near the occupied western regions situated along the Rhine clearly carried out by far the most extensive art acquisitions.

On the basis of the London Allied Declaration issued in January 1943, which declared all commercial transactions made by German nationals in the occupied regions to be invalid,10 France demanded that the museums return the acquisitions after the end of the war.11 Accordingly, many of these acquisitions are now in the holdings of the Musées Nationaux Récupération (MNR).12

Source: Archives de Paris, Comité de confiscation des profits illicites, 110W 64, Schenker company file.

West German museums in the regions along the Rhine

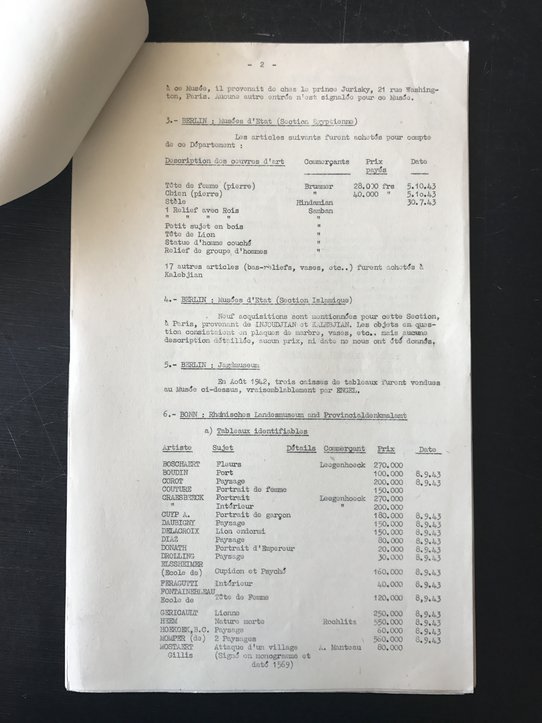

It is striking that a major proportion of the objects to be found among the MNR holdings had been acquired by museums from the northern Rhineland. It is also emphasised in the Schenker Papers that the number of acquisitions of some (Lower) Rhineland museums far exceeds those of all the others. The directors of the municipal collections in Bonn, Düsseldorf, Essen, Krefeld and Wuppertal, as well as Aachen and Cologne, travelled repeatedly to Paris, some of them together on occasion, for acquisition purposes.1 There they maintained the same contacts, in particular with Adolf Wüster,2 who among other things negotiated for them on the spot with French dealers, as well as with their colleague Felix Kuetgens, director of the Aachen Museums, who was stationed in Paris as a member of the Kunstschutz [German service for the protection of cultural heritage] and assisted with all the formalities.3 The highly ambitious head of the Rhenish culture department, Hans-Joachim Apffelstaedt,4 who wanted to establish greater prominence for the Rhineland as a cultural location, was directly responsible for the Rheinisches Landesmuseum in Bonn and a driving force in the acquisition undertakings of the museums under his authority.5 He therefore supported the directors of the Düsseldorf art collections, the Folkwang Museum in Essen and the Kaiser-Friedrich-Museum in Krefeld, who also cooperated from time to time, such as in organising the consolidated transportation of the objects acquired.6 The municipal museum in Wuppertal also took part in these activities. Only Otto Förster, director of the Wallraf-Richartz Museum in Cologne, aware of the culturally hegemonic position of the Rhineland’s metropolis, made his own way, for example acquiring art from France through Hildebrand Gurlitt.7

Based on indications from the Bonn art historian and Kunstschutz operative who was advisor to Göring in Paris, Hermann Bunjes,8 Apffelstaedt had initially nurtured hopes of being able to seize confiscated objects of Jewish ownership. Yet Hitler had other plans as to how to proceed with the confiscated art. In accordance with Göring’s instructions, it was first to be transported to Germany, after which any allocation to museums could be made,9 which never took place. No museum was given access; they had to limit themselves to buying art in the market with the—often substantial—funds granted to them by local political decision-makers.

In the Rhine–Main region, the mayor of Frankfurt, Friedrich Krebs,10 also had ambitions of securing works of Jewish ownership for his city, when he put in contact the directors of the Frankfurt museums11 and an operative of the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg (ERR) in Paris, Günther Schiedlausky.12 Krebs had declared the expansion of the municipal collections to be a focus of his cultural policy and commissioned the directors to travel into the occupied regions to acquire objects. To this end, he approved the release of substantial special funds, which benefited the Völkerkundemuseum (ethnological museum), the Städtische Galerie (municipal gallery), the Museum für heimische Vor- und Frühgeschichte (museum of local pre-history and early history), the Stadtgeschichtliche Museum (town history museum) and the Museum für Kunsthandwerk (museum of arts and crafts). The latter museum's director, Walter Mannowsky, was further entrusted with the organisation of furniture and household equipment by M-Aktion13 for the bomb-damaged city of Frankfurt. Following the annexation of the Alsace and its amalgamation along with the Baden Gau into the Baden–Alsace Gau a General Administration for the Upper Rhineland museums was established in the context of the ambitious cultural policy pursued by the Gauleiter Robert Wagner (1895–1946). This was assigned to the director of the Karlsruhe Kunsthalle Kurt Martin,14 who was also appointed as director of the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Strasbourg. In his new role, Martin made purchases above all for Strasbourg, which Wagner wanted to make the leading centre of cultural excellence in the Reich, and to an extraordinary extent art also in the occupied western regions, especially in Paris. Although Martin, an opponent of National Socialism, was at great pains not to acquire any works removed under conditions of Nazi persecution, such objects were still later identified among the acquisitions. After the war the artworks purchased in France, were brought from the Baden depot to Strasbourg, where they remained in the local collections at Martin’s behest.

Source: Archives nationales, Administration du commerce et de l'industrie, Commission nationale interprofessionnelle d'épuration, Peintres, Photographes; publicistes, hommes de lettres, F12 9633, Bulletin de renseignements sur les acquisitions faites par les musées et galeries allemands pendant l'occupation de la France.

Berlin

For individual collections of the Berlin State Museums as well,1 objects were acquired in occupied France. The director of the Egyptian department, stationed in Paris in 1941 as a Wehrmacht soldier, Günther Roeder, had sought out pieces in the art trade there that he wanted to acquire for Berlin. Yet it was not until 1943 that the necessary financial means were received. The directors of the Museums' departments in particular watched with growing concern as the uncurbed purchasing by other museums, especially those in the Rhineland, seemingly with inexhaustible budgets available, reduced the offering of high-quality works. In addition to primarily smaller objects acquired by the Egyptian and Islamic department from 1943, two paintings had previously been purchased by the Nationalgalerie.2 As the Berlin acquisitions after the end of the war were on the Museum Island in the Soviet sector and therefore beyond the reach of the western Allies, almost all of them are to this day in the ownership of the State Museums.

Source: Archives nationales, Administration du commerce et de l'industrie, Commission nationale interprofessionnelle d'épuration, Peintres, Photographes; publicistes, hommes de lettres, F12 9633, Bulletin de renseignements sur les acquisitions faites par les musées et galeries allemands pendant l'occupation de la France.

Source: Archives nationales, Administration du commerce et de l'industrie, Commission nationale interprofessionnelle d'épuration, Peintres, Photographes; publicistes, hommes de lettres, F12 9633, Bulletin de renseignements sur les acquisitions faites par les musées et galeries allemands pendant l'occupation de la France.

Austria and Switzerland

For some public collections in Austria, art was also acquired in Occupied France. So representatives of the Oberdonau Gau and the director of the art history collection of the Oberösterreichische Landesmuseum in Linz, Justus Schmidt,1 acquired artworks on the French market through the Austrian art expert Antonin Juritzky,2 based in Paris from 1938. On the journeys undertaken for this purpose, acquisitions were made for Heinrich Himmler as well as bought for personal use.

The Salzburg gallerist Friedrich Welz used his good connections with high-ranking Nazi officials and with the regional leaders of the Salzburg Gau among other things to purchase under their commission in France over 300 artworks for the Salzburg Landesgalerie, founded in 1942 by the Gauleiter Gustav A. Scheel and directed by Welz until 1944. Furthermore, Welz purchased additional objects for himself and his own commercial gallery.3 There are no comparable quantities of acquisitions to be recorded in Swiss museums. But here for instance the Kunsthaus Zürich through the agency of its advisor Charles Montag made some purchases in France during the war.4

Source: Archives nationales, Administration du commerce et de l'industrie, Commission nationale interprofessionnelle d'épuration, Peintres, Photographes; publicistes, hommes de lettres, F12 9633, Bulletin de renseignements sur les acquisitions faites par les musées et galeries allemands pendant l'occupation de la France.

Intermediaries and agents

Most museum directors or their colleagues travelled at least once into Occupied Paris for acquisition purposes. Yet they invariably also worked with intermediaries, mostly German dealers who had an extensive network available, tested the market, negotiated with their French colleagues, and also took over the formal transactions. Here it is important to mention above all Adolf Wüster, who was closely connected with the German embassy and probably the most important middleman for many museums along the Rhine.1 Not least through his good connections with the Occupation officials, he was able to assist in procuring the necessary export licences as well as frequently difficult foreign-currency transfers.2 Other intermediary dealers who conveyed works from France to German museums were, for instance, above all Hildebrand Gurlitt for Cologne but not exclusively,3 Rudolf Melander Holzapfel especially for Frankfurt,4 and Albert Loevenich, who worked predominantly for Nuremberg.5 The relations between museum directors and art dealers were thus interdependent, since dealers could greatly profit in the transportation of their wares to Germany as well as with foreign-currency licences and transfers from the privileges enjoyed by the museums in this regard. This sometimes led to highly complicated transactions that, partly on account of the complex network of participating actors, can today only be laboriously reconstructed and that obscure the origin of many works.6

Kunstschutz

To be able to export the acquired works, the museums’ buyers had among other things to report these to the military Kunstschutz, which was responsible for controlling the art trade as well as for protecting cultural assets from the impact of the war.1 The Kunstschutz operatives actively supported the German museums’ acquisition activities; in fact, some of them were themselves directors of collections in Germany. Thus, for instance, the above-mentioned Felix Kuetgens appointed as Oberkriegsverwaltungsrat [senior advisor to the Military Administration] at the Paris Kunstschutz was director of the Suermondt Museum in Aachen.2 In the regulation of the entry and export formalities, he was in particular an important support for his Rhineland colleagues, who for their part assisted him in the transport of the purchases he made for Aachen. Also the archaeologist Hans Möbius,3 from June 1941 Kunstschutz commissioner in Paris, was active until 1942 as curator and deputy director at the Kassel State art collections, before he was made a Professor in Würzburg and thus took over the directorship of the university’s Martin von Wagner Museum.4 For both these locations he bought predominantly but not exclusively antique art. The ambivalent dual roles of these representatives of the military Kunstschutz demonstrate how closely not least the politics of the military occupation was also connected at the personal level with the German museums’ acquisition policies.

Source: © Photo no. 432.714, Bildarchiv Foto Marburg / Photo: Beseler, Hartwig; recording date: 1940/1941.

Current state of research

Since the Washington conference in 1998, many museums in German-speaking regions have begun to examine their holdings for cultural property removed under conditions of Nazi persecution. In the context of conferences, publications, research and exhibition projects, they have shed light on their own history in National Socialism. To some extent acquisitions in Occupied France have thereby also been thematised. What can be inferred from this in the comparison across all the museums is the above-mentioned geographical focus along the Rhine, within which the museums that most actively enriched their collections through acquisitions in the Occupied Western regions are located.

Some French museums also made extensive purchases during the Occupation. National museums such as the Château of Versailles had special budgets available that clearly exceeded the financial means of the pre-War period.1 Accordingly, at many auctions French national museums exercised their traditional right of first refusal. Immediately after the war the Louvre exhibited the new acquisitions.2 In recent times the acquisitions of this period and their origin have begun to be more closely examined.3

The intensified provenance research in German museums has established that there too, now as then, are objects that originate from the French art market of the Occupation years but were not returned after the end of the war, as for instance in the above example of the Berlin museums.

So far the question of how to deal with acquisitions of this period has not been conclusively resolved. In the forthcoming reappraisal, it is important also to shed light on the way in which these objects have been dealt with in the history of the collections and on their associated discourses. Whereas in the immediate post-war period the acquisitions of German museums were predominantly considered from the perspective of unlawful enrichment, today the examination of a possible removal under conditions of persecution must be a core task. These challenges should be taken up by German and French museums as jointly as possible in transnational research exchange.

Basic data

Personne / personne

Personne / collectivité

Personne / collectivité