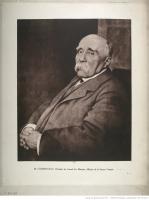

In the absence of a post-death auction and associated catalogue, the profile of Raphaël Collin as a collector can only be ascertained from rare sources. The painter, who did not travel to Asia, attributed his discovery of the Japanese civilisation to the dealer Hayashi Tadamasa (1853–1906). The latter, who came to France in 1878, specialised in the trade of Asian antiquities. Contributing to the popularity of japonisme, his Parisian gallery was frequented by collectors for twenty years as of 1884. The preface written by Collin for the posthumous sales catalogue of the Hayashi Collection provides precious information about how his own tastes developed: ‘I met Tadamasa Hayashi circa 1884 (…). He liked my outdoor nude studies, and he told me that he would like to own several of my most important paintings. In return, Hayashi initiated us, in his exquisite manner, to this unknown and wondrous world, from which he gathered the precious relics in his appartement on the Rue de la Victoire, and where each visit we made to his home was a source of pleasure and enchantment. I cannot truly describe the way he showed us fine pottery objects from Korea and Japan, beautifully modelled with the most sublime taste and the most inspiring of forms in an almost living clay […]. I visited Hayashi on many occasions and I was charmed by these fine objects that I dreamed of owning and which I now cherish’ (Illustrated Catalogue …, New York, 1913, p. 13). In his necrology of the Japanese dealer, Raymond Kœchlin (1860–1931) confirmed the role played by Hayashi Tadamasa in forming the Collin Collection: ‘We know the lacquer pieces and paintings [Hayashi] sold to Mr Vever, the sabre guards purchased by Mr Gonse, and the ceramic items acquired by Mr R. Colin [sic]’ (Kœchlin, R., Bulletin de la Société franco-japonaise, December 1906, p. 11).

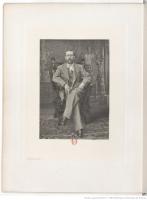

Before meeting the dealer, Collin was already interested in classical antiquities. A photograph held in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France dating from 1908 shows him in front ofa showcase in which small terracotta statuettes of the Tanagra type are lined up (Département des Estampes et de la Photographie, BNF, EI–13 (7), ref. ROL, 843). Later, his showcases housed ‘the finest netzkés, the most elegant of saké bottles (…), mizusashis, natsumés, tshavans, tchaïrés, and kogos, the many utensils required for the tea ceremony’. And in the workshop there were ‘Vases and statuettes from Bizen, faience pieces from Satsuma with fine craquelures and fine Korean stoneware (…) with embroidered foukousas (…) and vases from Seto, Shidoro, and Karatsu; unique and superb articles’ (Valet, M.–M., 1907, p. 761).

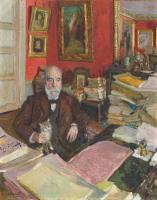

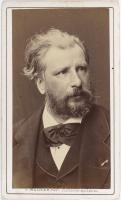

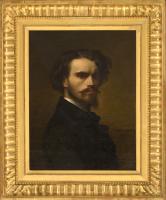

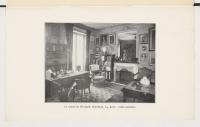

Like his contemporaries, Raphaël Collin sought ceramic wares, prints, sculptures, lacquer boxes, and tsuba (sabre guards). The objects, arranged here and there in his working space, were all around him: prints in portfolios, Noh masks on the walls, and screens that blocked off certain areas. There are rare photographs of his Parisian studio, located in the Impasse Ronsin, where most of the collection seems to have been held, amongst work that was underway and memories of his training. A photo of Edmond Bénard (1838–1907) from the series ‘Artistes chez eux’ is probably the oldest view. The painter is standing in front of a double portrait of children, probably Suzanne et Georges, exhibited in the 1886 Salon. Canvases and objects are cleverly arranged around the easels. A uchiwa type of fan can be seen on the wall and there is a screen often used by the artist in the backgrounds of his portraits. Hence, the objects in the collection were also used in his paintings. Marie-Madeleine Valet, a faithful contributor to the Bulletin de la Société Franco-Japonaise de Paris, who seems to have known the artist, explained that he used them as accessories for his models: hence, he painted the portrait of the granddaughter of Pierre Waldeck-Rousseau (1846–1904) holding a Japanese doll and the portrait of the young Maurice Gautier (1881–1965), holding a Japanese sabre with a lacquered coral scabbard. Marie-Madeleine Valet also described another unusual practice: the artist would arrange alongside his models Japanese pottery, which he used to establish complementary tonalities and, ‘in the voluptuous texture of a vase from old Satsuma, he perceived just as much beauty, finesse, and harmony as in the shadows that lay over a beautiful amber skin’ (Valet, M.-M., 1917, p. 20). The writer also explained that he would bring out of his boxes the ‘prints by the famous masters of the ukiyoyé‘, whose compositions he admired, and from which he gained much insight that he shared with his pupils’ (Valet, M.-M., 1917, p. 21). His disciples who returned home sometimes gave him Japanese objects. Raphaël Collin wrote: ‘Kume and Kuroda remained close friends. Now and again, my former pupils send me a postcard, object, or book’ (Valet, M.–M., 1913, p. 111). Hence, Kume Keiichirō said he had brought back from Japan five or six Noh masks to give to his master (Kume Keiichirō Bijutsu, 1916, p. 26). In return, Raphaël Collin no doubt gave them sketches of his pictures, which can be seen today in the Kume Museum in Tokyo and in the Municipal Museum in Kagoshima, as a result of Seiki Kuroda’s bequest to his native city.

The painter probably attended the major sales that dispersed the collections of the first generation of collectors. Two ceramic wares in his collection still have the labels of Parisian dealers stuck on their bases, including that of Léon and Marie-Madeleine Wannieck, the owners since 1909 of a gallery that specialised in directly imported Chinese art, on the Rue Saint-Georges in Paris (inv. nos. E 554–417 and E 554–103). In 1894, the artist had assembled a sufficiently rich and varied collection to be able to give an affirmative response to Gaston Migeon (1861–1930): thanks to the help of the pioneering connoisseurs of Japanese art—such as Siegfried Bing (1838–1905), Charles Gillot (1853–1903), Michel Manzi (1849–1915), Louis Gonse (1846–1921), and Philippe Burty (1830–1890)—, the curator was able to compile of a collection of high-quality Asian art intended for the Musée du Louvre. Collin donated five ceramic items: a raku bowl, a sixteenth-century Korean dish, another ‘decorated with a flower. Kenzan style decorations. Eighteenth century’, a pulpit attributed at the time to the ‘Outzi workshop from the end of the seventeenth century’, and ‘a kogo from the Ōhi workshop from the eighteenth century’, as well as a seventeenth-century bronze tortoise, and an eighteenth-century ‘white lacquered wood mask, with a calm expression’ . These objects are now held in the collections of the Musée National des Arts Asiatiques – Guimet with the inventory numbers ranging from EO 127 to EO 133. When, in 1905 Gaston Migeon published Chefs-d’œuvre d’art japonais, he reserved a special place for the Collin collection, including no less than thirty-eight objects that belonged to the painter, most of which were reproductions.

Collin’s support for the first public exhibitions of Japanese art means that we now have exhibition catalogues, which, without reproducing all of them, mention the objects entrusted by him. The artist was one of the loaners to the major exhibitions devoted to Japanese prints by the Musée des Arts Décoratifs between 1910 and 1914. We are aware, via Kume Keiichirō, that he had a particular liking for the works of Harunobu (circa 1725–1770), Kiyonaga (1752–1815) and Hokusai (1760–1849) (Kume Keiichirō, 1916, p. 89). The artist, who also took part in exhibitions of sabre guards in the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in 1910 and 1911, was also as a major collector of tsuba. Between 1910 and 1912, the Marquis de Tressan (1877–1914) wrote for the Bulletin de la Société Franco-Japonaise de Paris an article about the development of sabre guards in Japan, which was published in four parts (Tressan, G., 1910–1912). The pieces that illustrated the theme mainly belonged to the author, but, for the issues of June 1910 and June 1911, some were provided by Raphaël Collin. In 1913, alongside the main collectors of Asian art, such as Raymond Kœchlin, Henri Vever (1854–1942), Alphonse Kann (1870–1948), Madame Langweil (1861–1958), Georges Marteau (1851–1916), and Jacques Doucet (1853–1929), Collin loaned—for the fourth exhibition of Asian arts in the Musée Cernuschi devoted to Buddhist art¾two paintings on silk, two masks, three tsuba, five sculptures, and forty one ceramic articles associated with the tea ceremony. Initiated by Hayashi into the chanoyu spirit, the art of tea, and sadō, the path of tea, the artist does indeed seem to have been seduced by the very essence of the wabi-sabi aesthetic, its chawan (tea bowls) and mizusashi (recipients for cold water), whose rustic forms were the embodiment of Zen Buddhism’s quest for simplicity (Goloubew, V. and d’Ardenne de Tizac, H., 1913). ‘What attracted my master, Collin, amongst the Japanese things, was, aside from the polychrome prints, the more sober works of art, that is to say the ancient ceramic wares from Seto and tea bowls in the Korean style; he mainly enjoyed collecting objects with simple forms, without motifs, and in strange colours’ (Kume Keiichirō, 1916, p. 26). Collin frequented the collectors during public sales and the dealers Tadamasa and Bing, in particular during the famous Japanese dinners held by the latter. ‘He recalled the superb soirées that were once held in Gillot’s or Bing’s home, those unforgettable parties where one met up with one’s friends: Montefiore, Duret, Gonse, Clemenceau, Vever, and Kœchlin, all of whom were enchanted by this newly revealed art, all sharing in the same cult of japonisme’ (Valet, M.-M., 1917, pp. 21–22). Between 1907 and 1912, period during which Ichiro Motonō (1862–1918) was the ambassador of Japan in France, Collin also attended the diners held by the diplomat and his wife, who would wear ‘Japanese clothing’ for the occasion. The painter described these parties in letters he sent to his pupil Kume, who had returned to Tokyo. In one of them, he described a ‘Japanese style diner at the house of the Japanese minister in Paris, Mr Motono, with other friends of the arts of Japan and Hayashi’, after which ‘we looked at the objects’ (letter dated 8 July 1904 published in Kofu, Issue 1, May 1906). In 1910, as a member of the managing board, Collin joined the Société Franco-Japonaise de Paris, the other social hub for all the collectors. The same year, he went with the delegation to London to visit the ‘Japan-British Exhibition’, in which several of his Japanese pupils were exhibiting their works.

Following the painter’s death in 1916, the collection was dispersed. The only ensemble put up for auction, the tsuba were sold in Paris during the two auctions conducted by the firm Lair-Dubreuil on 12 and 13 May 1922, the sales catalogue comprising a total of 520 lots (Lair-Dubreuil F., Flagel L., Portier A., Hôtel Drouot, Paris, 1922). Blanche Collin (1854–1917) approached the Louvre with regard to her brother’s collection of Greek art. She recalled that she donated a gagaku mask (Musée Guimet, inv. EO 2426) and a two-leaf screen that belonged to him, a piece dating from the middle of the Edo epoch produced by the Rinpa School (Musée Guimet, inv. EO 2430). These objects were added to the core of the Japanese collections begun by Gaston Migeon, who was familiar with the screen as he had published an article about it some years earlier. As they were about to receive the Georges Marteau bequest, the painter Ernest Laurent (1859–1929) and the Louvre curator Paul Jamot (1863–1939) notified Henri Focillon (1881–1943), who was the director of the Musée de Lyon at that time, about the availability of the collection of Far-Eastern ceramics assembled by the painter. Focillon immediately went to Paris to assess the collection and, once there, drew up a short inventory of more than four hundred items, after consulting certain select figures, including the Danish painter and collector Charles Madvig (1874–1940). He quickly concluded that it was necessary to convince the mayor of Lyon to take the opportunity to acquire the objects. In the rapport he sent to the museum commission, he wrote: ‘He [Raphaël Collin] began assembling his collection about forty years ago, when collectors generally acquired prints, paintings, and bronzes. He constantly reviewed his acquisitions, to refine them. I believe that he primarily acquired his objects in London, but he also attended the major French sales that enabled him to purchase famous works. This is how the Collin Collection has attained the level of richness and maturity that it possesses today’ (AM Lyon, 1400 WP 007). The ceramic wares were bought by the Musée de Lyon for the sum of 60,000 francs. The art historian, who embarked on the study of Asian art, was fully aware of the significance of this acquisition, comprising in the nineteenth century more than four hundred articles dating from the sixteenth century, mostly from Japan and its different regions: Seto, Karatsu, Bizen, Hagi, Shigaraki, and Satsuma. The Japanese ceramic wares, mainly rustic stoneware associated with the tea ceremony, eighty-two Korean objects, and fifty-three Chinese pottery articles, including two mingqi statuettes, were donated to the museum over the summer of 1917. Focillon also took from Collin’s showcases, to add them to the lot, an Egyptian painted wooden sparrowhawk, ceramic pieces by Jean Carriès (1855–1894), three articles from William Lee (1860–1915), a small Etruscan bucchero vase, and nine antique iridescent glasses from Syria. The latter ensemble attests to the diversity of the Collin collection, which is as rich as it is unknown.

Article by Salima Hellal (translated by Jonathan & David Michaelson)