Nazi players and Institutions in the Context of the Spoliations in France during the Occupation

Unlike many other countries occupied by German troops during the Second World War, France was subordinate from the first day until the Liberation to a Militärbefehlshaber [military commander] whose headquarters were at the Hôtel Majestic in Paris. The legal basis for this was the Reichsverteidigungsgesetz [the law in defence of the Reich], which in the event of a war transferred executive power in occupied regions to the Oberbefehlshaber des Heeres [the army’s Commander-in-Chief]. The latter had to decide on all fundamental questions in agreement with the Beauftragter für den Vierjahresplan [Plenipotentiary for the Four-Year Plan], Hermann Göring, the Reichsinnenminister [Reich Minister of the Interior] Wilhelm Frick, and the Generalbeauftragter für die Wirtschaft [General Commissioner for Economic Affairs], Walther Funk.1 For the coordination in detail of civilian matters, the MBF (Militärbefehlshaber in Frankreich - Military Commander in France) was allocated an administrative staff in addition to his command staff. This was generally constituted of civilian officials who were appointed as Kriegsverwaltungsräte [war administrators] and wore a uniform.

In spite of all the preparations, the Oberkommando des Heeres (OKH, the army’s high command) was only inadequately prepared for the events and it soon fell behind as a result of the unexpectedly rapid advance by German troops in May 1940. When the Netherlands surrendered on 14 May, Hitler appointed Arthur Seyss-Inquart as Reichskommissar [Reich Commissar] and thereby removed the Netherlands from the OKH’s jurisdiction. It was only in Belgium, which surrendered on 28 May 1940, that the OKH was called on. General Alexander von Falkenhausen was appointed as Militärbefehlshaber with headquarters in Brussels and Eggert Reeder as head of the Militärverwaltung [German Military Administration]. However, their area of responsibility did not extend only to Belgium, but included the two Northern French departments, which at this time were already occupied by the Wehrmacht.

When the German tank divisions reached the Seine on 9 June after the end of the Battle of Dunkirk on their foray to the South, the OKH appointed Colonel-General Johannes Blaskowitz as Militärbefehlshaber of Northern France and ordered him on 13 June to form an administration for Occupied France excluding the departments of Nord and Pas-de-Calais. Blaskowitz took up headquarters at the Château des Sablons in Compiègne. Jonathan Schmid, former stell-vertretender Ministerpräsident [deputy Prime Minister] of Württemberg, became head of the Militärverwaltung. General Alfred von Vollard-Bockelberg was appointed as Stadtkommandant [Commander] of Paris, which was occupied the next day by German troops. He took up his headquarters at the Hôtel Crillon and the Ministerialdirektor [Ministerial director] Harald Turner became his head of administration.

After the Armistice with France on 22 June the Oberbefehlshaber des Heeres [the army’s Commander-in-Chief], Field Marshal Walter von Brauchitsch, took over himself for the time being the office of MBF in place of Blaskowitz. General Alfred Streccius became his deputy. Under Schmid, head of the administrative staff, Werner Best took over the administrative department and Elmar Michel the economic department. Colonel Hans Speidel was appointed head of the command staff. While von Brauchitsch resided at the OKH headquarters at Fontainebleau,2 Streccius, Speidel and Schmid took up their Paris headquarters at the Hôtel Majestic in Avenue Kléber.

After the failure of the Battle of Britain, the OKH headquarters was moved back again to Berlin. As Streccius had not proven himself, General Otto von Stülpnagel was appointed in his place on 25 October 1940 as the new MBF. Speidel and Schmid remained in office, as did the two Abteilungsleiter [Heads of department] Best and Michel.

Source: Fonds Franziskus Graf Wolff Metternich (Vereinigte Adelsarchive im Rheinland e.V.).

Organisation and jurisdiction

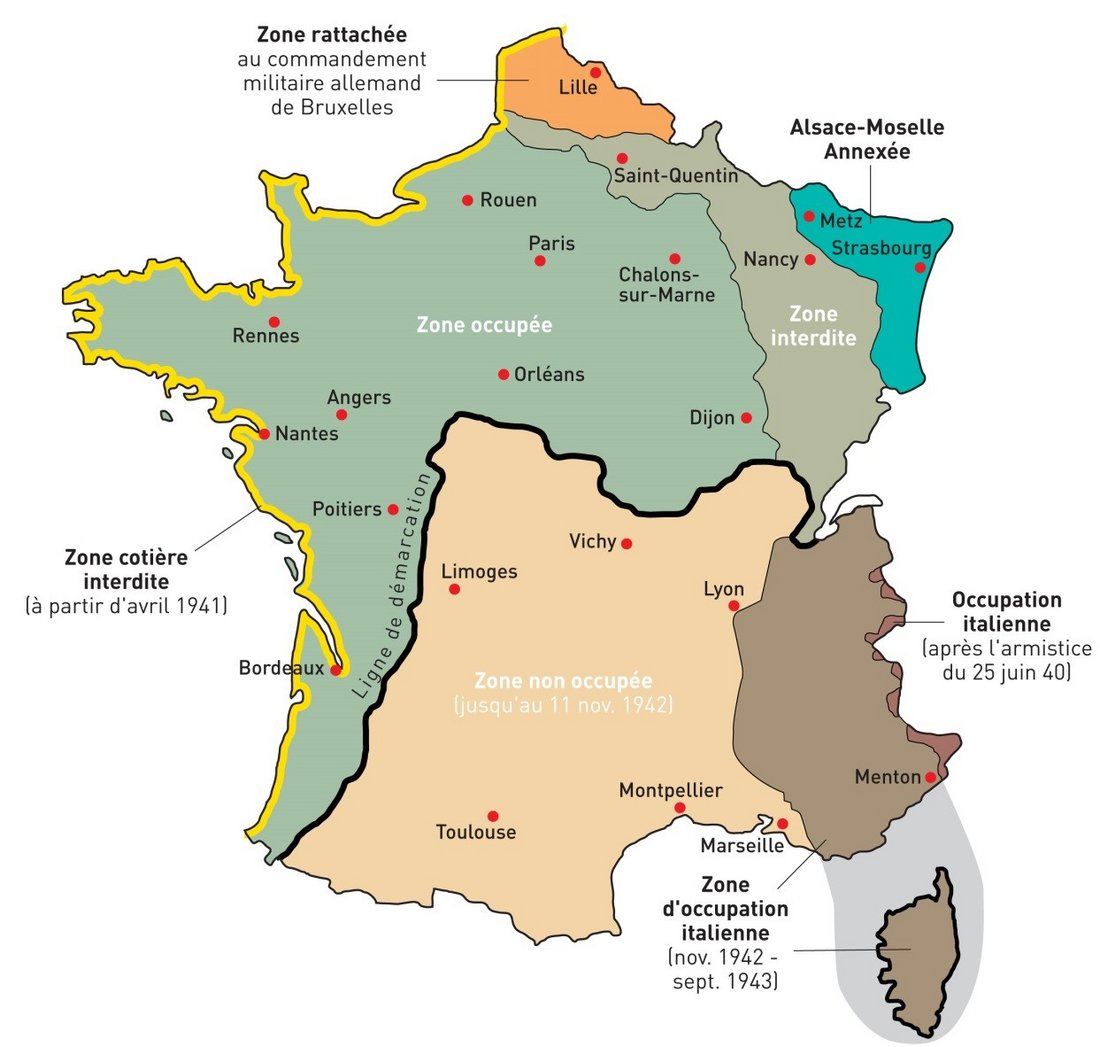

With the Armistice of 22 June 1940, the occupied part of France was divided into five military districts (North East France, North West France, South West France, Bordeaux, Paris). The departments of Nord and Pas-de-Calais meanwhile remained subordinate to the Militärbefehlshaber in Brussels. In Alsace and in Lorraine the Gauleiters Josef Bürckel and Robert Wagner were appointed heads of the Zivilverwaltung [Civil Administration] and were thus also removed from the MBF’s directional authority.

In the occupied part of the country every prefecture was allocated a Feldkommandantur [field command] and almost every subprefecture a Kreiskommandantur [district command]. In larger cities there was also an Ortskommandantur [local command]. With the Balkan Campaign in March 1941 and in particular after the invasion of the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941, this tightly woven network was gradually loosened. Of the 79 Feldkommandanturen and 152 Kreiskommandaturen some were either completely withdrawn, reduced to outposts or relocated, after the Wehrmacht’s invasion of the unoccupied zone in November 1942 and of Italy’s surrender in September 1943 respectively, moved as Hauptverbindungsstäbe [senior liaison staff] or Verbindungsstäbe [liaison staff] to Southern France.1 There, however, they were no longer subordinate to the MBF in Paris, but to the Kommandant im Heeresgebiet Südfrankreich [Commander of the Army Group Southern France], Lieutenant-General Heinrich Niehoff, whose headquarters were in Lyon.

The German fighting units stationed in France were subordinate not to the MBF but to the Oberbefehlshaber West [Military Commander for the West], Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt, whose headquarters were in Saint-Germain-en-Laye. The MBF only had a few Landesschützenbataillone [land defence batallions] as security troops and the Zollgrenzschutz [customs border guards], which from the end of 1940, in addition to protecting the coasts, took over from the Wehrmacht the surveillance of the demarcation line of the unoccupied part of France and the borders with Switzerland and Spain.

With the Balkan Campaign and above all with the invasion of the USSR in 1941, most of the German fighting units, with the exception of the Armeeoberkommando 7 (AOK, Army High Command) in Le Mans and the AOK 16 and, later on, the AOK 15 in Tourcoing and Roubaix were withdrawn from France. The focus of the German military presence in France shifted to the Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine. After the construction of the air-fields in northern France, Organisation Todt then took over the construction of the U-boat bases in Brest, Lorient, La Rochelle, Saint-Nazaire and Bordeaux. It was not until the end of 1942, after the British landing raid in Dieppe in August, that France moved again more strongly into the foreground for Hitler. After his order to build the Atlantic Wall, new fighting units were moved to France to resist an allied landing. In 1944 they numbered just one million men.

Power and powerlessness of the Militärverwaltung

This brief overview shows how limited was the room for manoeuvre in which the Militärverwaltung in France operated from the very beginning. Whereas in the early weeks, in consequence of the flight of over eight million people south, the main focus was initially on restoring everyday life, it very soon shifted to maintaining public order against the burgeoning resistance and in parallel with this the economic exploitation of the country.

In accordance with Article 3 of the Armistice of 22 June 1940, the Militärverwaltung exercised ‘In the occupied parts of France … all rights of an occupying power. The French Government obligates itself to support with every means the regulations resulting from the exercise of these rights and to carry them out with the aid of French administration’.1 However, there were no similarly clear instructions for the MBF also to implement the claim to sole exercise of executive power in France towards the German Dienststellen [agencies].

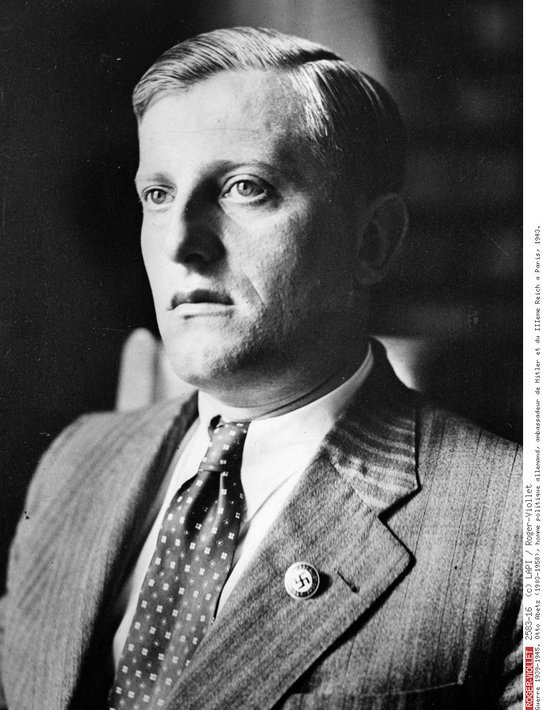

The OKH had obviously underestimated the desires that the crushing victory over France had triggered. When on 14 June 1940 German troops marched into Paris, hurriedly abandoned by a large part of its population, they were followed almost on their heels by the first representatives of a whole series of Reich ministries and Parteidienststellen [Party agencies].2 The very next morning, 15 June, Otto Abetz, later the German ambassador, arrived with his staff in Paris. It was no coincidence that in the search for a representative of the Reichsauβenminister [Reich Foreign Minister] Joachim von Ribbentrop to the MBF, the choice of all people had fallen on him. Abetz was no trained diplomat, but was considered for this as an established expert on France and he had the reputation that 'waiting for directives... was not his thing.’3

When Abetz arrived at the German embassy in Rue de Lille with his colleagues Carltheo Zeitschel, Ernst Achenbach, Karl Epting and Friedrich Grimm, they met Eberhard Freiherr von Künsberg with his staff, whom von Ribbentrop had ordered to search for French Files and Records.4 Künsberg, who shortly afterwards ducked into the building of the Polish Embassy, had not only searched offices but also a series of private homes belonging to leading politicians whereby he discovered, as Abetz described it, countless art objects and furniture. Abetz, who was ‘deeply convinced of the war guilt of the Jews, which in his view exposed them to harsh punishment’,5 derived from this the demand that vacant flats, in particular those of Jewish owners, be subjected to systematic inspection and that any art object found there should be 'secured'. Künsberg’s commando was too poorly staffed, however, to turn this thought into action. Abetz therefore turned for help to Helmut Knochen, who had been appointed by Heinrich Himmler on 20 June as Beauftragter der Sicherheitspolizei und des SD [Plenipotentiary for the security police and the security service of the SS] in France and made subordinate to the MBF.6

Otto Abetz and Franziskus Graf Wolff Metternich

Abetz took advantage of the fact that his powers as representative of the Reichsauβenminister with the MBF were not clearly defined.1 After the 1907 Hague Land Warfare Convention, the confiscation of private property without a prior peace treaty was banned, yet ‘the Franco–German Armistice agreement did not include a single word about art possession in France’.2 When the Beauftragte für Kunstschutz (Plenipotentiary for the protection of cultural heritage) in the occupied regions, Franziskus Graf von Wolff Metternich, who arrived in Paris a few days later, expressed doubts concerning the confiscations since carried out by Abetz, yet the latter explained that the Chef des Oberkommandos der Wehrmacht [Chief of the German high command], Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel, had on 5 July informed von Brauchitsch that Hitler had granted Alfred Rosenberg’s wish to search ‘state libraries and archives for documents of value for Germany’ in the occupied countries as well as ‘offices of the higher church authorities and lodges for political activities directed against us’. Reinhard Heydrich, the head of the security police, would ‘make contact with the appropriate Militärbefehlshaber [Military Commanders] for the purpose of carrying out the commission’.3

Certainly on 15 July 1940 the MBF issued a directive concerning the protection of artworks in Occupied France4 stating that seizing, removing or even changing the location of movable art treasures without written permission from the Militärverwaltung was a punishable offence. Yet Abetz was not deterred by this. When he was received by Hitler on 3 August at Obersalzberg, he took the opportunity and justified his high-handed actions on the basis of guilt incurred by the Jews as warmongers.5 After his return to Paris, Abetz - since 15 August now officially German Ambassador in Paris - insisted to Wolff Metternich that he had been commissioned with ‘securing the public and private, and in particular the Jewish art property in France’. The objects that he had stored in the embassy included artworks ‘that are not to become an object of the peace treaty but are to be transferred more or less immediately into the Reich’s possession as advance payments on reparation.6 Shortly afterwards, he also demanded access to the artworks from the Paris museums stored in the châteaux on the Loire.

With support from Best, the head of the administrative department, Wolff Metternich, certainly succeeded in bringing Abetz finally to relent on 28 September 1940. Yet Abetz’s explicit assurance ‘that confiscations of art property are now essentially ceasing and are only now to be undertaken by the Militärverwaltung or on the Führer’s written orders’7 in no way put an end to the dispute. For firstly the Militärverwaltung had thus strictly speaking abandoned its firm resistance to the theft of cultural assets.8 And, secondly, Wolff Metternich was now, in the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg (ERR), confronted with a new and even more powerful opponent.9

Source: © LAPI/Roger-Viollet, 2583-16.

Source: © Bildarchiv Foto Marburg.

Alfred Rosenberg and Hermann Göring

On 5 September 1940 Rosenberg reported to Best that in their search for written materials in France his staff members had ‘identified valuable cultural property in various locations. These are objects that are exclusively currently ownerless Jewish property. To protect these valuable cultural assets from theft, destruction or damage, I will transport these objects to Germany and have them secured there’.1 And before Best could point out to him the current legal position, Keitel explained to him that Rosenberg had received ‘clear instructions personally from the Führer with regard to the right to confiscate’ and that he was authorised to ‘dispatch cultural assets that he considered valuable to Germany and secure them here. As concerns their use, the Führer has reserved the decision for himself’.2

The tactics of the Militärverwaltung—instead of firmly opposing the wishes of the German Dienststellen [agencies] to seek solutions by means of negotiation—initially proved successful. The artworks stored by Abetz in the embassy were handed over at the beginning of October into the Einsatzstab’s custody and stored at the Jeu de Paume.3 As the ERR did not have the necessary transport capacities available and the Militärverwaltung did not provide any, the danger of a removal to Germany thus initially seemed to have been averted. Yet now with Hermann Göring a further opponent appeared on the scene.

Already in the run-up to the Western Campaign, Göring as Beauftragter für den Vierjahresplan had demanded that in the event of a victory France should be plundered and totally cleared out.4 This demand primarily concerned raw materials, armaments and industrial facilities, but also gold, precious metals and foreign currencies. Under his orders the advancing German troops followed hard on the heels of the Devisenschutzkommando [the foreign exchange protection commando]. They were under orders systematically to open safe deposit boxes and safes and to seize their contents in the name of the Reich. In addition to gold and securities, they also regularly got their hands on artworks and artefacts.5 As the Devisenschutzkommando was subordinate to the MBF, these were then handed over to the ERR for safekeeping.6

The Einsatzstab’s search for artworks and artefacts was in no way limited to the Paris region. When ERR staff members in Normandy wanted to search the Château de Reux, which belonged to Baron Édouard Alphonse James de Rothschild, they had to ascertain that the chateau—like many others in Occupied France7—had been seized by the Luftwaffe. When the ERR men demanded the handover of the artworks and artefacts that were in the Château, ‘this had an unforeseen side effect’,8 since Göring thereby obviously learnt of the Einsatzstab’s activity. With a keen sense of the opportunity opening up to him here, the ‘Third Reich’s second-in-command’ contacted Rosenberg’s representative in Paris, Kurt von Behr, and announced his visit to the Jeu de Paume on 3 November 1940. Two days later, he decreed on his own authority the future distribution of the works of art.9 Once Rosenberg had taken the precaution of checking back again with Hitler, a proper division of labour ensued: while the ERR took into custody all cultural goods seized by Abetz and the Devisenschutzkommando and continued to search systematically for Jewish art property, Göring decided on their distribution and organised the transport for their removal to Germany. ‘From top to bottom the Einsatzstab became a Göring show under the Rosenberg flag’.10

Until his dismissal as Beauftragter für den Kunstschutz in the occupied regions, Wolff Metternich then had to look on helplessly as Göring came regularly to Paris to view, accompanied by his advisor Hermann Bunjes, the cultural property seized by the ERR at the Jeu de Paume. Some of this was then transported to southern Germany and stored there for the planned ‘Führer Museum’ in Linz;11 the remainder was packed up into Göring’s Special Train and incorporated into the Reich Marshal’s art collection at his country estate Carinhall near Berlin.12

Source: © Ullstein Bild/Roger-Viollet, 87407-8.

Source: MEAE, Diplomatic Archives, 209SUP/992.

Conclusion

With Otto von Stülpnagel’s resignation as MBF on 15 February 1942 and Carl-Albrecht Oberg’s appointment as Höherer SS- und Polizeiführer [Higher SS- and police leader] in May 1942, the SS took over from the Militärverwaltung control of the police and the judiciary in France. Previously in March, Hans Speidel, head of the command staff, had been redeployed to the Eastern Front. In July 1942 the director of the administrative department, Werner Best, himself a high-ranking SS officer, moved from Paris to Denmark.1 Shortly afterwards, in August 1942, Wolff Metternich was suspended for ‘having displayed a distinctly Francophile attitude that is incompatible with the interests of the Reich’.2

Under the new MBF, Carl Heinrich von Stülpnagel, Elmar Michel was made head of the Militärverwaltung as Jonathan Schmid’s successor. At the Hôtel Majestic, the focus from then on was on the economic exploitation of the country, while Oberg and Knochen, in cooperation with the French Minister of Police René Bousquet, reacted to the growing resistance in the country with increasingly harsh repressive measures. With Julius Ritter’s appointment as Beauftragter des Generalbevollmächtigten für den Arbeitseinsatz [Representative of the Plenipotentiary General for the Deployment of Labour], Fritz Sauckel the Militärverwaltung one year later lost the responsibility in this domain as well, but at the same he time took charge of the organisation of the transports of French forced labourers to Germany as well as the deportation of Jews and members of the resistance—a division of labour that functioned smoothly right until the final days of the German Occupation.

Basic data

Personne / personne

Personne / collectivité

Personne / personne