The lawsuit filed by Paul Rosenberg against Theodor Fischer and Emil Bührle in the Swiss Federal Tribunal (1946–1952)

After the Second World War, Paul Rosenberg launched his own campaign to recuperate the many paintings stolen from him. This included his gallery in Rue La Boétie and pictures that were evacuated to the provinces and looted. It required a tremendous investigative effort to locate all the objects spread throughout Europe, as these had often been sold and resold many times.

The gallerist learned about the looting in 1941 while in exile in New York. He was also kept abreast of events in France through his regular correspondence with various artists, including Picasso, in particular about the systematic nature of the spoliation of Jewish property. His two brothers, Léonce and Edmond, had stayed in France, where they managed to survive in hiding. Incidentally, Rosenberg managed to send some of his gallery’s archives to London:1 these documents were crucial for the post-war investigations. Rosenberg filed lawsuits in France, using all the legal means at his disposal. It is difficult to determine how he found out that a certain number of his pictures had been transferred to Switzerland, where they were still located in 1946. The art historian and collector Douglas Cooper, a British official responsible for the protection of cultural assets in the Monuments, Fine Arts and Archives program, seems to have been an important source of information.2 By cross-referencing the information provided by Walter Andreas Hofer, Theodor Fischer, and Emil Bührle (he met the latter in Lucerne), Rosenberg came to the conclusion that there were seventy-five works in Swiss collections that needed to be returned, and which had previously been owned by eight different collectors.3 He provided the Swiss authorities with a list through diplomatic channels. This mainly concerned works dating from the second half of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth century. On 10 December 1945, after months of pressure from the Allied representatives, the Federal Council of the Federal Assembly adopted a law that imposed the restitution of all movable items. The text relating to the law had been modified the previous day by the Federal Council’s Financial Commission.4 One week later, the board of directors of Zurich’s stock exchange sent a letter to the Federal Council in which they protested against a law that ‘has been promulgated under foreign pressure and will surely be declared invalid under Swiss civil law’.5

Indeed, the law of 10 December was aimed at the restitution of securities that had been found on the territory of the Swiss Confederation, even though in the autumn of 1945 Douglas Cooper had seen the way in which the owners of pictures interpreted the text. In total, 803 lawsuits6 were filed before the special chamber of the Federal Tribunal in Lausanne, established after the decree of 10 December.7 This ‘Chambre pour les actions en revendication de biens enlevés pendant la guerre’ (‘Chamber for the reclamation of property looted during the war’) was composed of three professional magistrates, each of whom represented one of the Confederation’s three official languages. The lawsuits were admissible for all movable items that had been looted between 1 September 1939 and 8 May 1945 in the territories occupied by the Germans. This excluded objects plundered within Germany itself, stolen from German Jews, along with all those plundered in the territories annexed by the Reich before the outbreak of the Second World War. Also, the lawsuits had to be filed before 31 December 1947, which was an important restriction. ‘Later claims [i.e. those filed after 31 December 1947] [had] to be brought before the ordinary jurisdiction in Switzerland in accordance with articles 932 et seq. of the Civil Code (…)’, ruled Article 5. In addition, a possibility of appeal had been implemented: the sellers could be liable to claims made by the buyers of the works. The plaintiffs could be represented by the diplomatic missions. And lastly, good faith purchasers could take action against the Confederation and seek compensation from the Swiss public finances.8

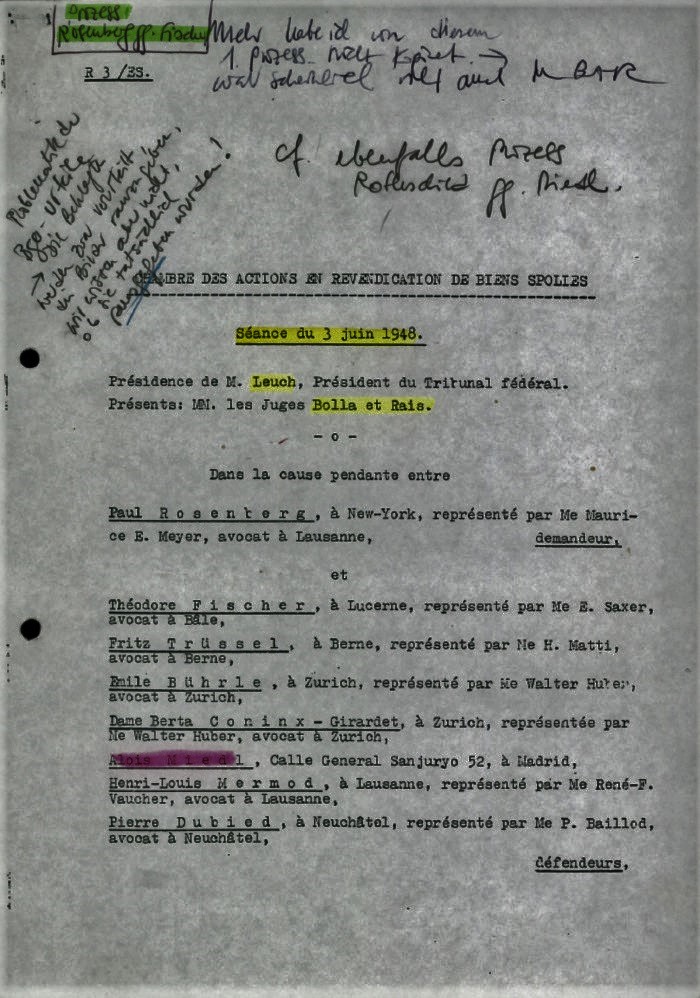

Paul Rosenberg was one of the first plaintiffs to attend a hearing at the newly established Chamber. His file bore the number 3. Acting through Maurice E. Meyer, a barrister based in Lausanne, he filed a lawsuit on 3 October 1946 against the following persons: Fischer, Fritz Trüssel, Bührle, Bertha Coninx-Girardet, Alois Miedl, Henry-Louis Mermod, and Pierre Dubied, all of whom were owners at that point of one or more of the thirty-nine pictures he was reclaiming. These included seven works by Corot, two by Daumier, two by Ingres, one by Courbet, four by Degas, one by Manet, one by Monet, four by Renoir, three by Cézanne, one by Pissarro, three by Seurat, one by Braque, one by Picasso, four by Matisse, three by Sisley, and Van Gogh’s Portrait de l’Artiste à l’Oreille Coupée. In 1940, Rosenberg had moved part of his gallery to Tours, then to the Château de Floirac in the Gironde region, and placed numerous works in a vault in the Banque Nationale du Commerce et de l’Industrie in Libourne. On 28 April 1941, the Devisenschutzkommando managed to open the vault with the help of a French locksmith. This Paris-based agency was an arm of Göring’s Vierjahresplan, or Four-Year Plan (rearmament), which operated throughout Europe confiscating hard-currencies and all sorts of securities.9 The contents of the vault were catalogued by François-Maurice Roganeau, director of the École des Beaux-Arts in Bordeaux, at the request of the Germans. On 1 August, a German civilian called Mr Braumüller, bearing a letter from the German organisation, confiscated the pictures and issued a receipt for 162 works.10 Rosenberg’s barrister based his claims on the description of the policy of looting art works implemented in France in the summer of 1940. The detailed account was based on documents published in Jean Cassou’s volume, Le pillage par les Allemands des œuvres d’art et des bibliothèques appartenant à des Juifs en France.11

Paul Rosenberg and his barrister attempted to reconstitute the itineraries of some of the works looted at Libourne (only a handful of these, as many have still not been found to this day), by revealing, in the lawsuit and in the subsequent memoranda, the information they had managed to gather. Most of the works had been acquired by Fischer, the gallerist from Lucerne, who, since 1938, had become one of the official fences for art looted by the Nazis. Hence, twenty-seven of the thirty-nine pictures reclaimed by Rosenberg had been acquired by Fischer. Fischer explained that he had obtained twenty-six of the twenty-seven works from Hofer, who was at the time the director of Hermann Göring’s collection and one of the major agents involved in the looting of works of art and their redistribution. Fischer specified that he had partly obtained these works in payment for purchases made by Hofer. In fact, these were pictures that were part of a number of exchanges of modern works—modern works Göring was only marginally interested in—for Old Master pictures. A twenty-seventh work had been bought by Fischer from Dr Hans Wendland. Hans Wendland was a German art dealer with a detestable reputation, and one of the most active dealers in plundered works. Fischer had sold five pictures to Bührle: Jockeys by Degas, a drawing titled Deux Femmes Nues by Degas, Manet’s Fleurs Dans un Vase, Port de Rouen Après la Pluie by Pissarro, and the picture Femme au Corsage Rouge by Corot. Courbet’s Femme Endormie had been sold by Fischer to Willi Raeber, who lived in Basel. Raeber had subsequently sold the picture to a certain Fritz Trüssel, a lawyer based in Bern.

Matisse’s picture Danseuse au Tambourin had been acquired by Bührle on 18 December 1942 at the Aktuaryus Gallery in Zurich. Toni Aktuaryus said that he had obtained it from a Mr Georges Schmid, who was believed to be the agent of Max Stöcklin, a Swiss living in Paris. The same Max Stöcklin had imported to Switzerland two pictures by Matisse: La Fenêtre Ouverte and Femme Dans un Fauteuil Jaune. He had sold them to the sculptor André Martin, who had pawned La Fenêtre Ouverte to the Neupert Gallery. Another picture had had an amazing itinerary before it finally reached Switzerland. Matisse’s Femme à l’Ombrelle au Balcon had been sold at the end of April 1943 by the Galerie de l’Élysée (Jean Metthey) in Paris to a certain E.-L. Bornand, a Swiss living in Paris. Bornand sold the work to Henry-Louis Mermod, an industrialist, collector, publisher, and patron from the Vaud region who was a major figure in Lausanne’s cultural milieu. Four pictures had been purchased by Alois Miedl from Walter Andreas Hofer: Van Gogh’s Portrait de l’Artiste à l’Oreille Coupée and three paintings by Cézanne, Arlequin, Nature Morte, Bouteilles, and Le Garçon au Gilet Rouge. Miedl, another notable profiteer of the Nazi spoliations of art works, was living in Madrid in 1948.

Another picture had been sold directly by Bruno Lohse, Göring’s agent in Paris,12 and had passed from one owner to another, including once again Toni Aktuaryus, who sold it to Bertha Coninx. La Petite Pêcheuse was sold by the Neupert Gallery to the Tanner Gallery (Zurich), which then sold the work to the industrialist Dubied.

In March and April 1948, Martin, Dubied, and Coninx stated to the ‘Chambre pour les actions en revendication de biens enlevés pendant la guerre’ that they were willing to hand back works they had acquired and which had originally belonged to Rosenberg. Subsequently, the lawsuit brought against them was dropped. Fischer, in contrast, attempted by all means to refuse any restitution of works and his barrister contradicted—somewhat irrationally—the two memorandums filed by Meyer. Combative from the outset, Fischer had requested via an act of 24 November 1947 that the securities he had transferred for the acquisition of the pictures should be made available. The Federal Tribunal rejected this request. In the two memorandums filed, he asserted that he considered the Decree of 10 December 1945 illegitimate, as he stated that it had been issued solely in application of special powers granted to the Federal Council in wartime. Switzerland remained a law-abiding state throughout the war and was one of the few countries in Europe to maintain its integrity, but the Federal Council had taken exorbitant decisions of common law, in particular in relation to the organisation of the economy, rationing, and national defence. This remark was thrown out, as the judges of the ‘Chambre pour les actions en revendication de biens enlevés pendant la guerre’ argued that the Decree of 10 December 1945 had been issued following a vote by the Federal Assemblies. Fischer then stated that the dispossession of French Jews had been organised by the French government in conjunction with the German occupiers and that, consequently, Rosenberg’s claim was no longer valid. Fischer affirmed again that, while he acknowledged that the pictures in question had indeed been the property of Rosenberg, the latter were not in fact plundered. Borrowing the very words of the confiscating German authorities, he claimed that the German measures were simply intended to protect works whose owners were absent. Based on a passage from Jean Cassou’s book—in a distorted interpretation—, he even stated that the objects looted from Maurice de Rothschild at 41 Rue du Faubourg-Saint-Honoré had been bought and duly paid for with a bank cheque. Lastly, Fischer claimed that the confiscations had been validated by a clause in the Franco-German Armistice Agreement of June 1940. It is interesting to note that, in an attempt to justify his fantastical assertions, Fischer produced copies of letters from two members of the ERR (the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg) in Paris, Karl Brethauer and Gerhard Utikal, both of whom had been placed in preventive detention in France at the time. He did not explain how he managed to obtain the documents, but it seems that the network of looters and dealers established in France continued to operate after 1945.

All of the works were located and the Federal Tribunal had obliged their owners via an ordinance of 3 March 1947 to place them in storage in the Bern Museum of Fine Arts; this was enacted. Henceforth, the Museum was responsible for the sequestration of works of art, whose handling and conservation it was entrusted with. This procedure guaranteed the implementation of the Federal Tribunal’s decisions.

On 3 June 1948, the Chamber ordered that all the works should be returned to Rosenberg. Fischer and the other purchasers of looted pictures were ordered to pay the plaintiff’s legal fees and compensation for the expenses incurred for employing an agent and the subsequent investigations undertaken. All the pictures were returned to Rosenberg by the Bern Museum of Fine Arts. The Rosenberg/Fischer/Bührle verdict was a landmark decision for subsequent lawsuits filed to retrieve looted objects. On 15 December 1948, Fischer was ordered to return five pictures to the Lévy de Benzion estate, works which had been taken from almost a thousand others looted from the Château de la Folie in Draveil (Essonne), including Corot’s San Giorgio Maggiore;13 on 15 December 1948, a Van Gogh was returned to Alfred Lindon;14 and, on 7 July 1949, ten works were returned to the Alphonse Kann estate, including Renoir’s Forêt à Fontainebleau.15

Arguing in favour of the possibility of compensation for good faith purchasers of looted works, Fischer filed a lawsuit with the Federal Tribunal and requested reimbursement for the works he had acquired (or even exchanged). An initial hearing was held on 5 July 1950 in Lausanne in the presence of the plaintiff and his barrister Küno Müller.16 Here again, Fischer adopted a combative approach and readily put forward unconvincing arguments. While he admitted that he had met Hofer just before the war, he denied that he knew about his activities. Fischer contradicted the rumour that he had visited at least once the Jeu de Paume (repository of confiscated French Jewish collections) during one of his three trips to occupied Paris. And he stated that he had been in contact with the Jewish dealers who worked with Hofer, including Zacharie Birtschansky. As Birtschansky had taken part in these complex transactions, Fischer stated that he had considered at the time that it was a guarantee of integrity. ‘I wasn’t aware that Jewish dealers were looted’, he declared to the three judges.17 The minutes of the hearing are curious: the arguments put forward by the representative of the Confederation’s financial administration show that Fischer could not have been unaware of the provenance of the pictures, as he was entirely involved in the transactions. However, the judges decided in favour of Fischer, in the name of the preservation of the principles of Swiss civil law—that is to say property rights—, which was considered to override any other consideration. In a decision of 25 June 1952, Fischer was awarded compensation of 200,000 Swiss francs, with a complement of 5% interest as of 30 June 1948.18 Bührle then filed a lawsuit against Fischer, again bringing a claim before the Chamber. He too was awarded financial compensation.

Hence, the legal proceedings undertaken by Rosenberg in Switzerland against Fischer, Bührle, and consorts were particularly complex. They served as models for later restitution lawsuits, even though most of the work carried out by the special chamber concerned securities. The decree of 10 December 1945 was effective: all the reclaimed pictures were returned to their rightful owners. Only one item was not returned: a sixteenth-century portolan that had been the property of Alexandrine de Rothschild. The many documents relating to these cases show the extent of public awareness in the post-war years. They also attest to the state of law with regard to the restitutions: the spoliations were considered exceptional and the rights of the legitimate owners had to be recognised, but in parallel the decision was taken to inflict no financial penalties on the art dealers who had participated in the plundering of art works and benefitted from this. In fact, Switzerland was not the only country to introduce legislation in relation to looted works in occupied Europe, as Sweden introduced similar procedures.

Bührle bought one of the works that he had been obliged to return. In contradiction with what is often written, he did not come to an agreement with the rightful owners (the Alphonse Kann or Rosenberg estate) to keep the works, but had to recommence the purchasing process and buy them back. This was true of the painting by Degas titled Madame Camus au Piano.19

"Patrimoine spolié" Seminar : Le procès Paul Rosenberg contre Emil Bührle, Suisse 1946-1951

Jean-Marc Dreyfus - 19 avril 2023

Basic data

Personne / personne

Personne / personne