French Museums during World War II

On Sunday, September 3rd 1939, France declared war on Nazi Germany. Throughout history, from the destruction of the Jerusalem Temple in 70 C.E. to the plundering of the Bagdad museum in 2003, confiscations and large-scale lootings have existed, but none can be compared to those of the Second World War, when the threat to the French patrimony was perhaps the most dire in the history of the country, after the Revolution. A great deal of research has been done involving Rose Valland and the spoliation of Jewish property.1 Research sources and publications are also available on the history of museums – archives produced by French and German administrations2, testimonies published by the actors of the times,3 monographs,4 acts of colloquia5 and exhibit catalogs.6 This field of research is extremely timely, and includes both recent publications and an abundant “grey literature” issuing from university research.7 Unlike the First World War, French society had prepared itself for war, however much it did not want to believe in the inevitability of a new conflict. With the defeat, the Third Republic disappeared, giving Marshall Pétain free rein to lead the French state. Once the debacle was over, although the show went on in the artistic world, it was marked by antisemitism and the rejection of works deemed “degenerate” by the occupier.

Source : © Archives nationales, 20144792/250, photo 77.

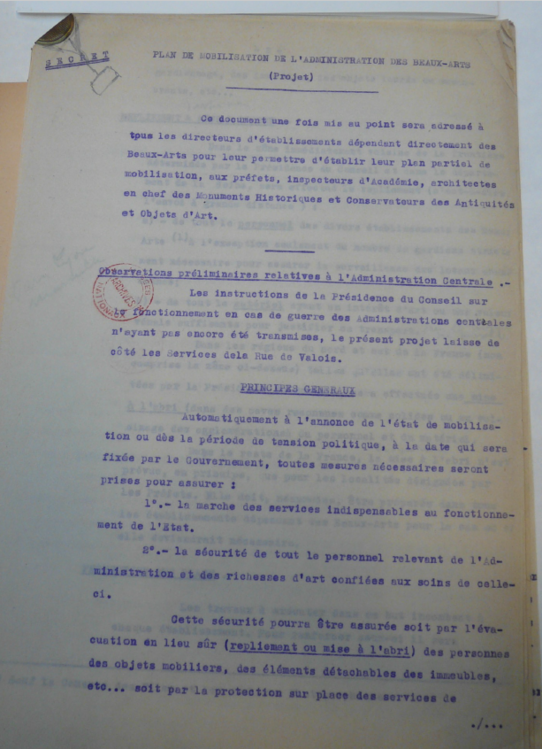

Preparing for the war

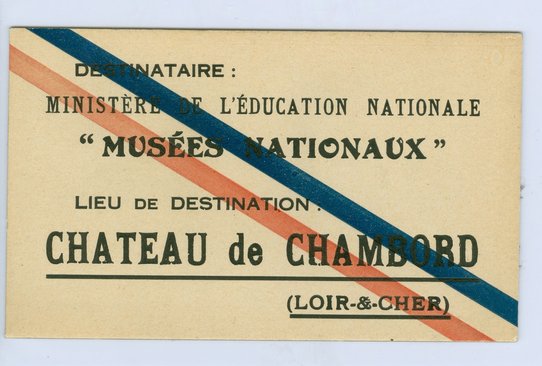

During the inter-war period, the presidency of the Museum Council was worried about preserving the patrimony in case of war. The subject of organizing another evacuation was brought up as of February 1930,1 making the 1939 evacuation the only one planned and thought out in advance and not a case of emergency, as it had been in 1870 and 1914.2 Fears soon focused on the need to protect buildings from air attacks, and the evacuation of the Prado3 during the Spanish civil war helped introduce model measures.4 In 1936, Henri Verne gave curators the task of drawing up lists of “especially important works in need of sheltering, and works with a less urgent need for protection, but that could also be evacuated.”5 At the same time, Joseph Billiet, associate curator of national museums, inspector of provincial museums, was in charge of “establishing in order of urgency the lists of artworks to be evacuated or protected in place in case of an international conflict”6 for regional museums. The planning task was immense, replacement sites had to be found for all the museums in France.7 On 19 May 1938, the château de Chambord was designated the main depot, despite its many disadvantages.8

A dress rehearsal took place before the Munich summit, when a first convoy left the Louvre on 27 September 1938. The artworks found their galleries, but “Chambord, too visible, already too well-known by the public, could not be retained without heavily engaging the responsibility of the Beaux-Arts administration,”9 all the more so since the press had learned about the evacuation.10 After the 1938 failures, the plan for “moving the museums of Paris and its periphery was pushed to a maximum”11 under the direction of Jacques Jaujard, Verne’s associate. The Louvre created coded lists of its works and divided up its collections between hundreds of crates.12

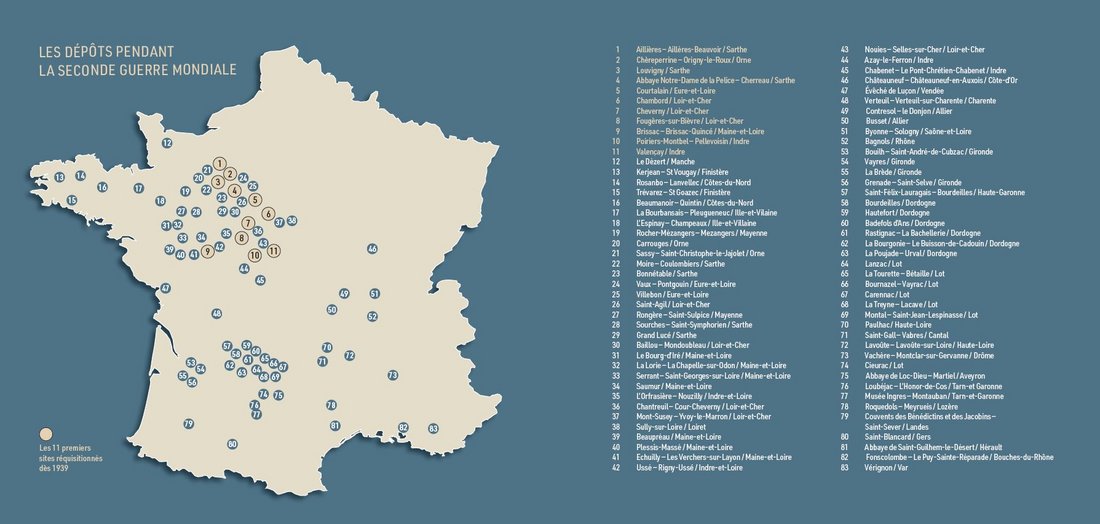

On 24 August 1939, the non-aggression pact between Germany and the Soviet Union became public and curators received the order to evacuate.13 Certain foreign countries and important collectors entrusted their most precious objets d’art to France, and the collections of 200 provincial museums were taken to 71 depots.14 In a few days, a third of French public collections was evacuated.15 Faced with German advances, another evacuation was necessary in May-June 1940.16 The Louvre’s paintings department was sent to the abbaye de Loc-Dieu in the Aveyron, but conservation conditions were unsatisfactory and for the 3,120 evacuated paintings involved, the exodus continued on to the musée Ingres in Montauban.17 In 1943, for fear of bombings, the Louvre’s paintings were displaced a last time to the châteaux of the Massif central.18

Aside from restoration campaigns and emergency evacuation exercises, their daily lives were relatively calm until the combats of the Liberation, though they were marked by German inspections supervising the presence of artworks and by the looting of collections entrusted to the museums.

February 1930.

Source : Archives nationales, Archives des musées nationaux, Série R, 20144792/18.

Source : © Archives nationales, 20144792/20.

Source : FLEURY Alexandra, Chambord 1939-1945 : "Sauver un peu de la beauté du Monde", Chambord, Domaine national de Chambord, 2021, 96 pages © Frédéric Célestin – Domaine national de Chambord.

The museums during Vichy

After the dismissal of Georges Huisman, Louis Hautecœur, former curator of the musée du Luxembourg, was named director of the Beaux-Arts from July 1940-March 1944, followed by Georges Hilaire, close to Pierre Laval. Under the supervision of the successive Education ministers – Jérôme Carcopino, then Abel Bonnard – these men, along with Jaujard, named director of the Musées de France1 managed the lives of museums.

The Versailles, Compiègne and Fontainebleau châteaux and some galleries of the Louvre re-opened with limited collections and copies to give German soldiers the pleasure of visiting the museums.2 Various plans to reorganize the Louvre and national museums were being studied,3 but the most notable event of the period was the inauguration at the palace of Tokyo on 6 August 1942, of the Musée national d’art moderne “to avoid the Modern Art museum being requisitioned by the occupation troops.”4 655 artworks were exhibited, with the exclusion of paintings by Jews, foreigners, or political opponents. In application of the laws on the status of Jews, exclusion also struck the personnel of the museums, among them Jean Cassou, close to the communist party, married to the sister of Vladimir Jankelevitch, who briefly headed the Musée national d’art moderne before being dismissed and replaced by Pierre Ladoué, former associate of Hautecœur at the musée du Luxembourg.

While the country was occupied, museums acquired many works, facilitated by the simplification of procedures.5 Budgets were granted exceptional subsidies6 and credited with 60 million francs for the pre-emptive purchase of artworks among the collections under escrow measures.7 These conditions allowed the museums to be particularly active on an overheated art market, supplementing “public collections with works to be admired in the Louvre galleries,8 while seeking, sometimes, to “lessen the distress of persecuted collectors.9 Such was the growth of the collections, that in 1945 George Salles asked: “How did we succeed, during the storm, in acquiring so many riches?”10 If we look at the lists of acquisitions, “we can only observe troubling concomitances between the subjects chosen and the conservative ideology deeply permeating minds at the time.”11 At the Louvre, numerous purchases were made: “it is important to acquire, on one hand, great masterpieces, worthy of the our Museum’s ‘class;’ on the other hand, works that are minor, but that bear essential landmarks for the History of French Art.”12 It was thus that artworks sold in escrow, issuing from lootings and forced sales, entered the public collections – officially, “to withdraw from the occupant’s lootings works whose artistic value demands their being maintained in France”13 – the dispossession of Jewish owners seemingly not an afterthought.

Administrative reorganization was based on a draft law of 10 August 1941, published in the Journal officiel on 9 November 1941 strengthening the powers of the Musées de France and originating in a 1937 draft law on museum reform. The law created a “regime of museum common law”14 and revolved around four principles: museums other than national museums to be classified and supervised, the putting in place of a declaration for the creation of a museum, the obligation to consult the technical committee of the Réunion des musées nationaux for all acquisitions, donations or legacies, the verification of the competences of curators by means of an aptitude list and a national framework, lacking until then.15 The law was an attempt to solve some of the pre-war problems of cultural institutions, all while expressing the will to control and strengthen the central power of the Vichy regime.

Resistance grew in the national museums: Jean Cassou (dismissed, and later imprisoned), joined the shadow army as of July 1940, later it was the turn of René Huyghe and André Chamson; Jaujard was close to several networks and along with Billiet, multiplied oppositions to the ministry’s administrative demands. But there was also a real antisemitism, as can be seen in the correspondence between Germain Bazin and Huyghe,16 and part of the museum community did not hesitate to collaborate: among others, Georges Grappe, curator of the Musée Rodin,17 very active president of the Plastic Arts section of the Collaboration group and organizer of the Breker exhibition at the Orangerie.18

Source : © Martinière / Archives nationales, 20144792/250, photo 66.

Source : © Archives nationales, 20144792/250, photo 64.

Occupants and museums

In July 1940, German ambassador Otto Abetz gave the order to seize all objets d’art, whether they belong to the state, to cities, or to Jewish owners.1 Franz von Wolff-Metternich was put in charge of protecting works of art in the Kunstschutz. Metternich did seek to protect the French patrimony; nonetheless, in the guise of safeguard, cultural objects of Germanic origin and works that could have something to do with the Reich were listed with a view to claiming them at the peace treaty.2 For interfering in the looting policy of the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg (ERR), Metternich was replaced by his associate Bernhard von Tieschowitz, who pursued his action.3 The works in the museums of Alsace-Moselle were recuperated by the German army in August 1940 and returned to their original departments, reannexed to the Reich.4

On November 1st 1940, the Jeu de Paume museum was occupied by the ERR to organize the looting of private collections belonging to French Jews. Objects were expertized, photographed, then sold, exchanged or kept for the benefit of Nazi and Reich leaders. Rose Valland, a museum employee, was retained at her post by Jaujard to spy on Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg (ERR) operations, and the data she amassed in her Carnets testify to their daily exactions.5 Among the collections plundered were those entrusted to the national museums in 1939 by the Rothschilds, Léonce Bernheim and David David-Weill, former president of the Conseil des musées de France – hoping in this way to protect them.6 Approximately 60 private collections in 500 crates were thus evacuated at the same time as public collections and placed in museum depots.7 Attempts by the National Museums directorate to protect the works of private owners became a failure as of July 1941.8 The volume of operations is staggering: several tens of thousands of artworks were seized in France between 1940-1944.

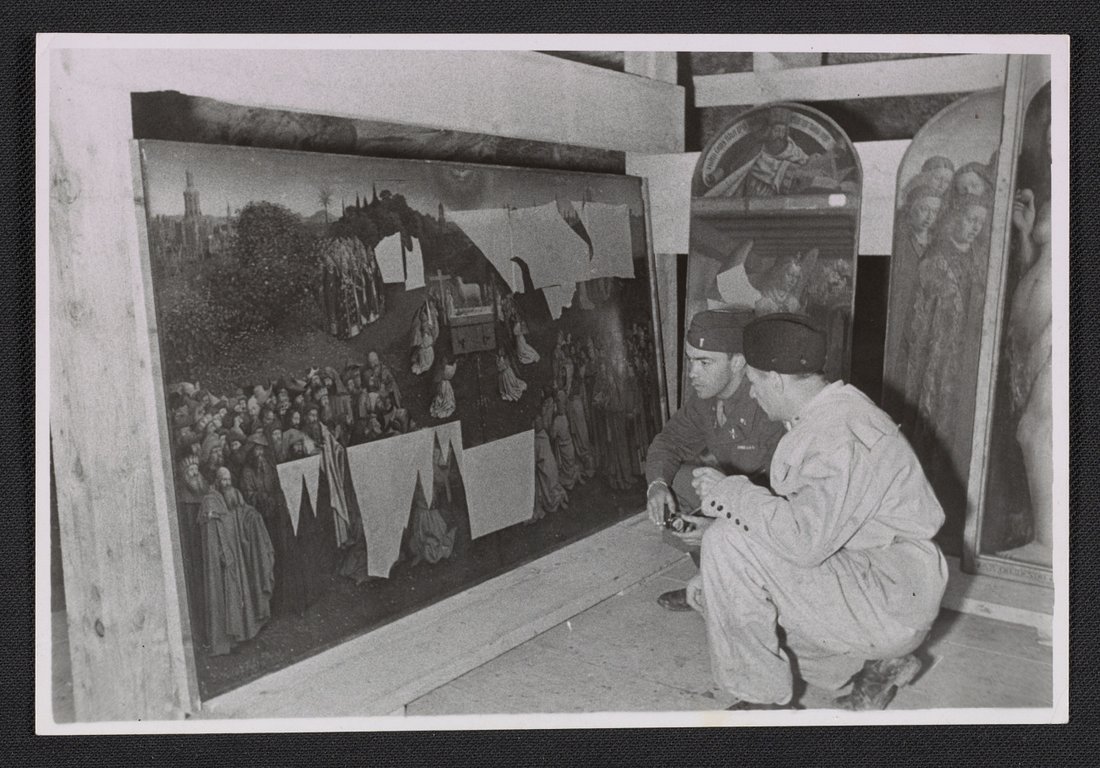

Another slap in the face suffered by the museums was the spoliation of L’Agneau mystique entrusted to France by Belgium. Despite a system of protection put in place by Jaujard, Metternich and the burgomaster of Gand,9 on 3 August 1942, the painting left for Germany following a decision by Laval.10 Jaujard protested, for which he earned a reprimand from Bonnard.11

Jaujard was nonetheless able to refuse the demands of certain Nazi leaders. Ribbentrop wanted the Diane sortant du bain of Boucher, Himmler, the Bayeux Tapestry, and Göring, the Antependium of the Basel cathedral. Jaujard managed to slow down the process thanks to an exchange principle refused by the German curators.12 However, a number of works from national collections were carried off to Germany, such as objects from the military collections of the Invalides, considered “spoils of war” and La Madeleine of Gregor Erhart.13 Although exchanges with Germany did not take place, one with Franco’s Spain was successful: Murillo’s L’Immaculée Conception left the Louvre for the Prado, along with six of the nine visigothic crowns of Guarrazar and the Dame d’Elche. In exchange, France received a Portrait de Covarrubias by El Greco and L’Infante Marianna, then attributed to Velasquez.14

Source : © Aufnahme-Nr. 432.714, Bildarchiv Foto Marburg / Photo : Beseler, Hartwig; Aufn.-Date : 1940/1941.

The perilous road towards the Liberation

In 1944, the Occupation authorities attempted to repatriate the depots towards Paris. Jaujard stalled the process, pointing to the increase in bombings in the Paris region,1 and citing the example of the Sèvres museum hit by bombs in March 1942.2 The depots finally remained in place, joined by additional crates following the evacuation of the museums in the North, Northwest and coastal regions.3 To protect them, Jaujard informed the allied staff of their position through the intermediary of Spain.4 As the territory was liberated, the depots were visited by officers of the Art Looting Investigation Unit, who placed them under the protection of the allied forces.5 There was no damage to the Louvre, despite the proximity of the combats, when the Free French Forces marched up the rue de Rivoli toward the hôtel Meurice, headquarters of the German military staff.

Destruction and lootings did however take place. In Metz, where combats were particularly violent, museum collections were severely damaged. The Liberation revealed what the Aryanization of the collection actually meant in the annexed regions. Edmund Hausen, director of the Metz museums beginning in 19406 reported on the “degenerate vision of history to be seen in the Metz museums, totally opposed to the German character of the country and the population of the Lorraine.”7 The Überleitungsstelle für das volks- und reichsfeindliche Vermögen (entity in charge of the managements of the goods of the enemies of the Reich) set up business inside the museum.8 The several thousands of spoliated items were brought in, listed and photographed,9 then either sold or put at the disposal of the “colonists” replacing the expelled Mosellians.10 After return to France,11 escrow and the complexity of the formalities for the return of works prevented the reopening of the museum and led the conservation department to request the departure of looted objects, supposedly according to the instructions received from the directorate of the Musées de France.12

Jaujard, named director of the Beaux-Arts, was followed by Billiet, then Georges Salles at the new directorate of the Musées de France. They immediately requested reports on the state of French museums,13 gradually opening with the return of collections.14 Functionaries of the Beaux-Arts were hardly troubled during the purge.15 Only Bonnard was condemned to death, but in absentia, having fled to Spain. Hilaire was condemned, also in absentia, to five years in prison, Grappe was discharged from his function. Symbolically, the Commission de récupération artistique installed its offices in the Jeu de Paume on 24 November 1944. Rose Valland continued her action there, tracking down and recovering works that had disappeared in Germany.16 Thus began the long road to their restitution and to the compensation of those dispossessed.

Basic data

Personne / personne

Personne / collectivité

Personne / personne