Comité ouvrier de secours immédiat (COSI) (EN)

The Workers Committee for Immediate Aid (COSI) was a humanitarian body created in Paris during the Occupation that became a tool for propaganda and collaboration. Auctions organized by the COSI were a secondary source of supply for several Parisian dealers.

Photograph by André Zucca (1897-1973). Bibliothèque historique de la Ville de Paris.

Source: © André Zucca/BHVP/Roger-Viollet, 74662-28.

Photograph by André Zucca (1897-1973). Bibliothèque historique de la Ville de Paris.

Source: © André Zucca/BHVP/Roger-Viollet, 74662-30.

COSI: its creation and objectives

The Workers Committee for Immediate Aid (COSI), an entity created in Paris during the Occupation, has been perceived by several historians ambiguous in nature, given on one hand its humanitarian intent and on the other, its service as an ideological tool of collaborationist propaganda.1 Recently, the historian Jean-Pierre Le Crom deepened the origin, functioning and role of the COSI.2 Gilles Morin furthered the analysis in 2019, detailing the role and practices of COSI’s union leaders.3

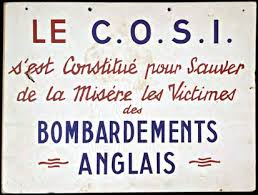

COSI was created a few days after the first allied bombing of a big French enterprise. British aviation, in its attack on the Renault plants in Boulogne-Billancourt on 3 and 4 March 1942, destroyed homes and killed and wounded hundreds among the workers population. A small group of collaborationist union leaders, closer to the German occupant than to the Vichy government and that nurtured the working-class base of collaborationist parties, took part in the initiative to create this “humanitarian” organization to aid victims.

During a meeting at the German embassy, the proposal was made by par Charles Vioud (1893-1965), editor of the anticommunist and anti-Semitic brochure Les Riches doivent payer (“The rich must pay”), René Mesnard (1902–1945), member of Marcel Déat’s Rassemblement national populaire (RNP), and Jules Teulade (1890–1974), member of Jacques Doriot’s Parti populaire français (PPF).4 COSI was supported by Ferdinand de Brinon (1885–1947), French government delegate in the occupied territories, and supervised by the representative of the German embassy, Rudolf Schleier (1899–1959). As of its creation, COSI’s action was situated on a political level, its aim being to denounce Allied destruction and to strengthen French-German collaboration. It was a propaganda and collaboration tool destined for workers milieus. It fanned out to the provinces, founding committees of victims that broadened its action and social surface.

The sums redistributed to the victims’ families, the operating expenses of COSI and its activities were financed by the fine of one billion francs imposed on Jews in the North zone,5 but not only. “Besides the billion franc fine, COSI recuperated furniture from the properties seized from Jews by the Germans and intended for distributing to victims of bombings. This furniture was stored in the Rozan factory in Montrouge. Its distribution causing difficulties, COSI then had it auctioned.”6

COSI was liquidated by Order dated 22 August 1944.7 It seems the directors were living a high life and that corruption was the rule. “We consider that over half the sums at their disposal were used fraudulently.”8 However, when it came to finding the money and punishing those responsible no real solution was found. In August 1944, its president, René Mesnard and his collaborators fled to Germany and set up COSI in Tuttlingen. Leaders and members of COSI faced justice beginning in September 1944. Mesnard was killed in March 1945 and Kléber Legay9 succeeded him as president of COSI.

Gilles Morin notes that the purge was kind to COSI’s unionists,10 the fact they belonged to COSI being considered secondary. Their humanitarian action, which was real, was more important, in the eyes of justice, than their collaborationist engagement. He feels that “at the Liberation, COSI’s exact nature was not well understood. This misestimation contributed to playing down its real role, including in historiography.”11

COSI and the art market

The role of COSI in the art market has to this day not been researched by historians. In the archives of the Récupération artistique are catalogs of sales put together in 1943 by COSI’s president, René Mesnard.1 It was thanks to the tenacity of an artist, the painter Francis Harburger, that COSI was identified in 1948 as an actor in the art market.2 The private archives of Harburger on that subject3 are stored in the Mémorial de la Shoah.4 In April 1948, Francis Harburger alerted the lawyer Robert Kiefé and Albert Henraux, president of the Commission de récuperation artistique, on the role of COSI.

An investigation took place in 1948 and 1949. On 14 May 1948, Robert Kiefé5 told “senior judges”6 of his intention “to bring to court, on behalf of the C.R.I.F., the attorney-general responsible for the repression of economic collaboration.”7 He met with the examining judge on 15 October 1948. For his part, Albert Henraux questioned the employee in charge of sales and asked for “the sales records and names of the main buyers.” There followed a correspondence between the two men between the 2nd of May and 20 September 1948.8 The employee sent Henraux the sales catalogs and names of buyers. The catalogs9 revealed that between January and July 1943 there had been seven sales of paintings, engravings, drawings, pastels, etchings and watercolors. Henraux brought this information to the attention of Raymond Lindon,10 replacing the attorney-general of the Paris appeals court, on 25 September 1948.11 The government commissioner at the court of justice answered that a pre-trial investigation had been initiated concerning the affair and that an inquiry had been ordered. Albert Hernaux received the following information and documents:

- Sales were made singly or by groups (of 5 to 10 works)

- Buyers are identified. Some are present at several of these sales.

- Among the approximately one hundred identified buyers, several are known in the Paris art market,12 such as probably the gallery owner Louis Carré, Georges Aubry, Étienne Pouget, Paul Tulino, Jean Schmit and the gallery owner Georges Terrisse, as well as the auctioneers Georges Blond, Alphonse Bellier, Doctor Simon, collector, and van der Klip (?), director of the gallery Berri-Raspail.13

- Where identified, the works proposed for sale are very varied: engravings and watercolors by reputed painters, (André Lhote, Albert Lebourg, Henri Harpignies, Paul Signac, Othon Friesz, Francis Picabia, etc.), drawings by well-known artists (Jean-Louis Forain, Maximilien Luce, Théophile Alexandre Steinlen, François Boucher, Puvis de Chavanne, etc), works of Dutch masters, paintings by Ledoux, Othon Friesz, Charles Kvapil, Léon Zack, André Favory, Théodore Rousseau, Luce, Armand Guillaumin, Harpignies, Félix Ziem, etc etc.

- Prices range from 100 to 62 000 F.

Activities revealed by an artist’s investigation

Objects belonging to Francis Harburger (1905–1998) were looted in Paris in two separate places and seemingly by two different circuits:1

– In 1940 he stored about fifteen canvases (his and those of his collection) in the vault of the Alliance israélite universelle (AIU) ),2 45 rue La Bruyère – these were looted and sent to Germany by the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg (ERR) in early August 1940.3

– His atelier and apartment, located at 15, rue Hégésippe-Moreau in the 18th arrondissement, were looted at the end of 1942 (or beginning 1943), seemingly under the heading of the looting of apartments belong to Jews, by the “Möbel Aktion.”4 “COSI recuperated furniture from properties taken from Jews by the Germans.”5

On his return to the city in 1945, Francis Harburger actively searched for his stolen paintings, with no success. In February 1948, he found one of his works, Les Lavandières,6 for sale in the Vanves flea market.7 He bought the painting at the stand of a seller at the market, Mme Chevalier, and returned to Vanves several times (March 13, 14) in an effort to understand how that canvas happened to be there. He made inquiries in Vanves and in Sceaux.

He noted his findings in manuscript and transmitted them to Robert Kiefé, a lawyer, and to Albert Henraux.8 He met with flea market sellers9 and also (18 and 22 March) the employee who organized the sales. He also consulted the lists of biddings, noted the dates of eight sales, noted the presence of old masterpieces that had been sold singly, and others in lots, as well as the names of those who acquired them. He figured out that the sales had been realized in Sceaux for COSI, whose president was Mesnard.

Harburger then transmitted to Henraux the name and coordinates of the administrator in the Sceaux city hall in charge of the sales. On the basis of Harburger’s inquiry, Henraux questioned him and retrieved the sales catalogs, then informed the law court that had already examined the affair, and to this day it is unknown whether the case was closed or ended with a decision. In the light of recent research, we assume that in 1948 Francis Harburger had led provenance research as far as possible. He had identified a collaborationist and mafia-type circuit for the sale of artworks on a market parallel to the official market of auction houses. That market was known to and frequented by certain market actors, gallery owners and collectors.

Conclusion

Several questions remain unanswered today, and various research axes deserve to be deepened. It remains unknown whether the 1943 sales were exceptional or whether other sales of artworks can be attributed to COSI. Nor has recent research shown whether the sales price of artworks corresponded to their market value: beginning in 1942, both single works of art and precious cultural objects collected by the Dienststelle Westen (Service for the West) in the context of Möbel Action (Furniture Action) were given over the ERR, and since it remained competent for the “transfer” of this particular type of plunder, the links between COSI and the ERR, could be questioned, as well as the knowledge the German authorities had of such activities.1 The conclusions of the 1948 judicial inquiry should also be researched. In the end, the sales catalogs contain a wealth of information for provenance research.

Source: Private collection, Bernard Lamorlette.

Source: Private collection, Gilles Morin.

Basic data

Personne / collectivité