OLIJ Herman (EN)

Hermanus Olij was a Dutch businessman who worked for the Germans during the Occupation under the name Dr. Alfred Bosch. He was responsible for the transport to Germany of artworks, notably for the art dealer Hildebrand Gurlitt.

A family with National Socialist sympathies

Hermanus Cornelis (Herman) Olij was born in 1898 in Landsmeer, a small village to the north of Amsterdam.1 Olij’s family had early sympathies towards the National Socialist movement in the Netherlands. Numerous members of his family would become active for both the Nazi party and/or the fascist movement during the thirties and forties. Most notably is Herman’s brother Simon Paulus ‘Sam’ Olij (1900-75), a former Olympic boxer who was to become one of the most active members of the Ordnungspolizei (“Public Order Police”) in the Netherlands. He tracked down dozens of Jews who went into hiding after the full scale deportations started in 1942.2 During the crisis years of the early thirties, Olij joined the new Dutch fascist party, the Nationaal-Socialistische Beweging (NSB).3 He left in 1934 after being a member for only eight months. Although he didn’t rejoin any official national socialistic organization he began, soon after the invasion of May 1940, to work for the German occupation forces.

The beginnings of collaboration: a cover for the Abwehr (Defense)

This collaboration began when Olij met a man named Leo Harry Abas (1905 - missing after 1945), a Dutch-German Jew from Hamburg.1 Although Abas introduced himself as a traveling businessman, he was actually working as a German Abwehr agent since the early 30s.2 Exactly how and where the two men met remains unclear, but Abas did introduce Olij to his superiors Aike Meems (1891-1955) and Gerard A. Dierks (1895 - unknown), brother of the influential Abwehr agent Hilmar G. J. Dierks (1889-1940).3 After several meetings Olij was accepted as a new recruit and brought to Hamburg for special training in code writing, radio transmitting and performing missions in enemy territory.4

After his return from Hamburg, Olij received instructions for a mission to England.5 He was to drop off a fellow agent by boat on the English coast, but due to technical malfunctions the mission was a failure.6 After Olij’s return home he blew his cover as an Abwehr agent by telling several people about his failed trip. Having become useless for Dierks’ department, Olij was transferred to the Abwehrstelle Wilhelmshafen, run by Dr. Helmuth Meijer (1898-1945). This department focused on economic espionage and sabotage.7 Olij was given a new identity with the name of Dr. Alfred Bosch, a German philosopher and businessman, which was in line with his previous job as a traveling salesman. He also established a new company called ‘Concern. Dr. A. Bosch, Amsterdam’. It was used for general import-export but mostly functioned as a cover for Abwehr activities. It was located at his home address, the Stadionstraat no. 11. Since his new position required him to travel abroad he requested a Dutch passport in his own name and received an official German passport in the name of Dr. Alfred Bosch.8

Business flourishes, he meets Gurlitt

Olij’s surviving business records show that during the summer of 1941 he travelled extensively to Hamburg, Berlin, Brussels and Paris performing several jobs for both the Abwehrstelle Hamburg and Wilhelmshafen. He set up a new office in Brussels at the Rue Vilian XIV no. 41 called ‘Handelsonderneming A.D.O.C.’.1 It was first headed by Johannes van der Pol, a Dutchman from Naarden, later replaced by Adele Oppenrieter-Andritz (born 12.10.1908), originally from Vienna and who was to become one of Olij’s mistresses.2 Olij also claimed to have an office in Berlin, at the Einemstrasse no. 7, and offices in Krakow and Vienna but no proof of that has been found. Through his superiors and fellow agents he became acquainted with several businessmen throughout occupied Europe. One of them was the art dealer Hildebrand Gurlitt (1895-1956).

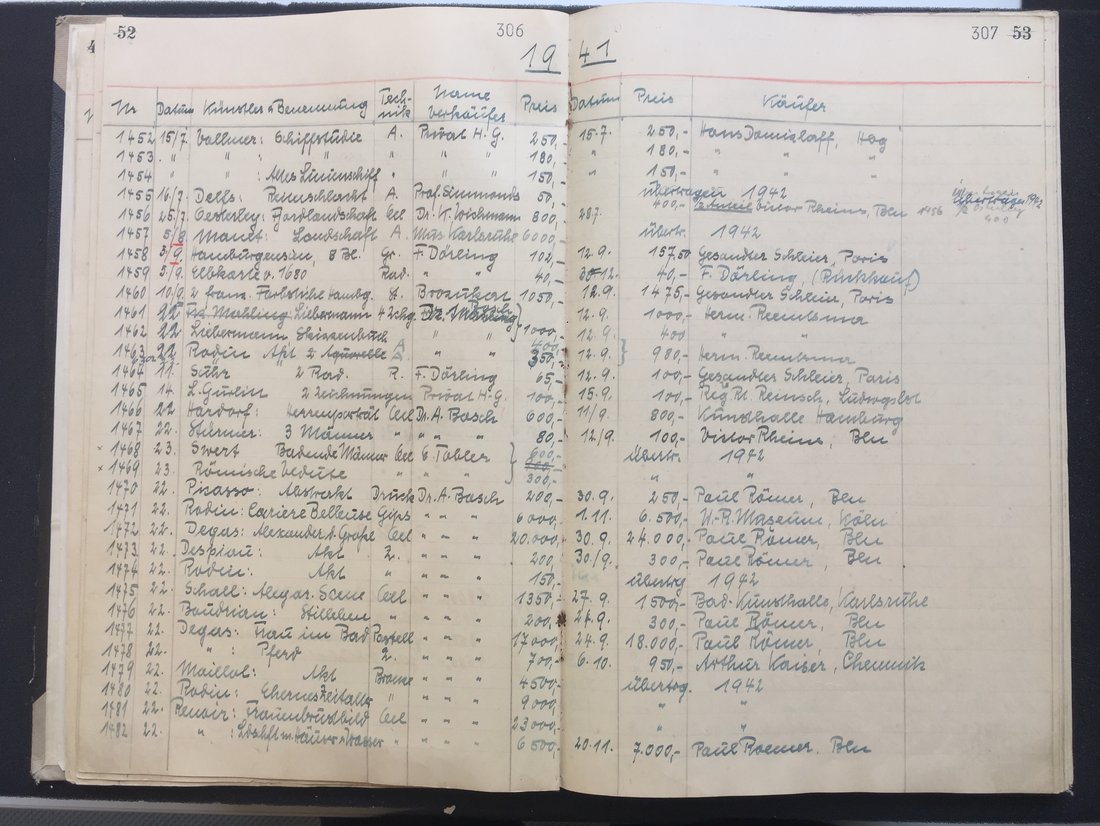

Gurlitt’s records show a transaction with one of Olij’s companies, ‘Dr. A Bosch, Amsterdam’, in September 1941.3 His business ledger records an ensemble of 45 mostly French statues, pastels, drawings and oil paintings by artists such as Rodin, Degas and Renoir that changed hands for a total amount of 164.650 RM,4 a remarkably small amount of money considering both the quantity and presumed quality of the works involved. That the description of the works is extremely minimal, that no dimensions are mentioned and the titles are very generic, makes it very difficult at present to identify individual artworks.5 Extensive research into Olij’s background showed that he had neither the money nor the connections to amass this ensemble of artworks. Consequently, we assume that by acting as the ‘owner’ of the works he helped Gurlitt with their export from France to Germany.

The French government had put into effect a series of rules and regulations that prevented, or at least complicated, the export of cultural assets abroad.6 Since Gurlitt couldn’t arrange these permits himself, he probably decided to use someone like Olij, who had experience in the import-export business, to do this work for him. Olij’s company appears only once in Gurlitt’s records, but Gurlitt made several more of these transactions, and in 1942 convinced another person, Jean Lenthal, to help him with transport. Lenthal was an Austrian Jew who worked as an art dealer in Paris, and whose real name was Hans Loewenthal (1914-1983). This time it was he who acted as the owner of 44 mostly French artworks.7 After the war, Loewenthal admitted that he only provided the necessary paperwork, since Gurlitt’s request was ‘a favor he couldn’t refuse’.8 Olij and Loewenthal together were involved in only one transaction. This was probably because Gurlitt got in contact with the Dutch art dealer Theodorus Antonius Bernardus Maria (Theo) Hermsen (1905-1944), who from then on was willing to provide Gurlitt with all the necessary paperwork.9 Gurlitt explained these transactions after the war by saying that the owners refused to sign official documents because they didn’t want to be accused of collaboration.10 It could also be that Gurlitt tried to cover up a problematic provenance involving theft or looting.

A growing number of offices, meeting places for the Abwehr

By 1942 Olij’s business was going well, since he was able to hire several ‘real’ sales agents to provide him with a steady income.1 He had relocated to a bigger office at Eerste Constantijn Huygensstraat 105 in Amsterdam.2 All his offices were to become Abwehr meeting places, where a number of agents would come to collect wages, hold meetings and drop off reports. In 1943 Olij managed to establish a new branch of his firm in Paris called Generale Machines Handels mij.3 It was set up with the help of Suzanne Bouquerot (born 8.2.1914),4 whom he had met during one of his trips to the French capital. She had worked at the cabaret Ciro in rue Daunou until she decided to start working for the Germans in 1942.5 The office was first located at her house, 14 rue du Colonel Moll, but was soon relocated to an impressive office building on the corner of rue Washington and the Champs Elysées, at no. 104.6

Bouquerot quickly hired several employees, there being no dearth of the latter, since the Germans were demanding more and more people for the Arbeitseinsatz (Work mission), and working for Olij exempted them from being called to Germany. In the fall of 1943 the new office had a translator, Philippe Edouard (born 27.6.1912), two bookkeepers, Jacques André Marie Luylier (b.19.9.1914) and Jean Birge/Johann Birg (Jewish), (b. 17.4.1910), two sales managers, Guy Pillet (b. 26.10.1910) and Serge Jacques Antonin Placide (b. 25.9.1915) and two secretaries Jeanne Marie Madeleine Pillet-Daupias (b. 31.12.1914) and Leonie Octavi Remy-Rosotto (b. 15.7.1895).7 Like the offices in Amsterdam and Brussels, the new French office also functioned in two ways, to provide an income for Olij and at the same time cover up German Abwehr activities. Suppliers of the firms were import and export companies with generic names like UNIGEX and SOGEX. According to Pillet they delivered their goods to a nearby company called PRIMETEX, on rue Washington and to the German organizations located in the occupied Figaro office building.8 Bouquerot’s closest German contact was a lieutenant from the SD or Gestapo called ‘Dr. Berger’.9 He also provided her with a German identity and a so-called Durchlassschei (permit) giving her the possibility to travel freely through occupied Europe.

In 1944 things started to change for Olij. Due to his extravagant lifestyle and large number of questionable deals made the previous years, Olij got into financial problems. To refinance his businesses he had printed a series of completely worthless bonds and shares for one of his companies, the ‘N.V. handels- en financierings maatschappij Holland-Duitsland.’.10 Olij sold the bonds and shares in Paris during the summer of 1944. This action solved his money problems on the short term but didn’t resolve the issues he had with his dissatisfied clients and business partners. Considering the amount of documentation involving lawsuits, settlements and complaints in his remaining business records, it was only a matter of time before Olij’s luck would run out. When he failed to deliver a large shipment of tiles to a German businessman, things got out of hand: the businessman demanded his money back, but Olij refused, physically assaulting him and, to settle the dispute, forcing him to accept a fraction of the money Olij owed him.11

The German businessman reported the incident to the police, and at the same time, Olij’s irregular presence in Paris caught the eye of the French authorities. On July 1st 1944 Olij was arrested by the Amsterdam SD (Sicherheitsdienst, Nazi Party intelligence office) for assaulting a German citizen, committing fraud and embezzling funds from the Wehrmacht.12 His Amsterdam and Paris offices were sealed by the German authorities. Olij’s wife, Jansje Veneman (1903-93), destroyed all the business records she could find in the Amsterdam offices, Suzanne Bouquerot did the same with the administration in the Paris branch.13 Adele Oppenrieder moved to Amsterdam with her infant, Monique Julia Rose Marie (born 26.1.1943), shortly before the Liberation, but soon after left for an unknown destination.14 Since Olij had kept parts of his records in a safe at a local banking firm in Amsterdam, they were out of his wife’s reach. The allied authorities later confiscated them and started their investigation into Olij’s activities. Most of his staff was arrested and questioned, but later released, and whether or not any of them were prosecuted remains unclear.

Herman Olij was eventually transferred by the SD to the Stadelheim Prison in Munich from where he was released on 19 July 1945.15 The allied forces soon arrested him again for various crimes including the betrayal of several Jewish people and the looting of their possessions.16 The Americans released Olij after two more years in the Civilian internment camp no. 74 in Ludwigsburg.17 By 1947 all of Olij’s staff, business partners and family members had been questioned by the Dutch government and his court case was prepared, the authorities only waiting for Olij’s transfer back to the Netherlands. Like thousands of others, after the war Olij was accused on a number of counts, though little could be proved beyond doubt. France could no longer provide (financial) information involving possible crimes committed during the German Occupation to foreign countries, and as a result, in his remaining records, there is no detailed information on Olij’s transactions in France. Nor is there any detailed information concerning his office in Brussels. All that remains are statements by his associates and his own business records. Olij was eventually prosecuted for (economic) collaboration with the Germans and sentenced to five years in prison, losing his voting rights for the rest of his life.18 Most of the artworks that Olij helped to export for Gurlitt to Germany were sold by the latter to his regular clients, among whom the industrialist Hermann F. Reemtsma (1892-1961).19 After the end of the war some of the artworks were located and confiscated by the allied forces, either from Gurlitt’s holdings or his clients’ collections. Since their pre-war provenance remained unclear, most of the French artworks were eventually returned to France, where the government transferred them to the Musées Nationaux Récupération (MNR) collection.20 Further research into the provenance of each of the artworks involved in Olij’s transaction will be necessary to establish their whereabouts and original owners, and rule out a problematic provenance.

Source : Base POP.

Source : Base POP.