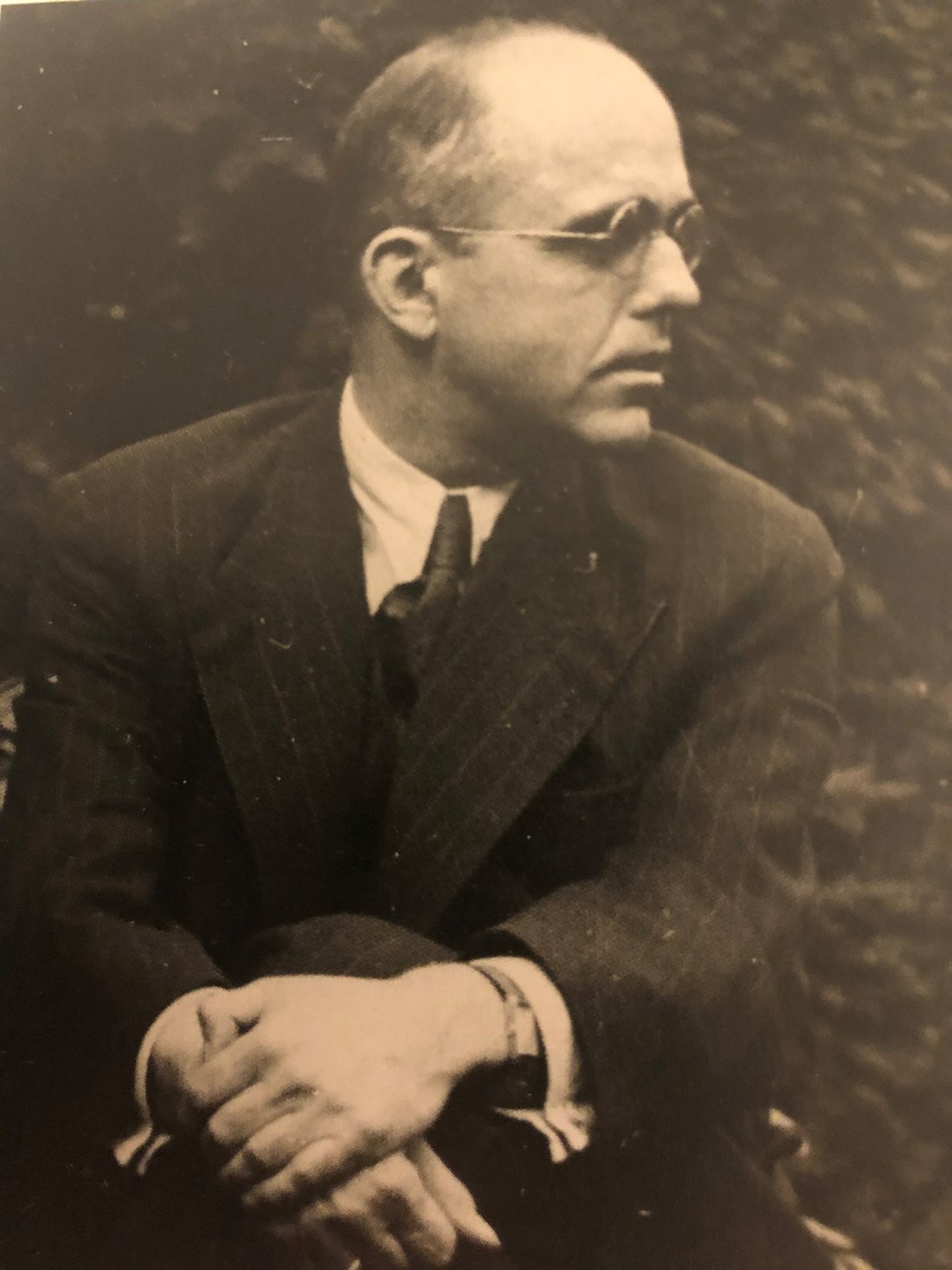

GURLITT Hildebrand (EN)

The German art historian and art dealer Hildebrand Gurlitt championed the breakthrough of modern art during the Weimar Republic and was later involved in Nazi art looting.

Origins

Born on 15 September 1895 in Dresden, Paul Theodor Ludwig Hildebrand Gurlitt came from a large, culturally influential family that included painters, musicians, art historians, gallerists, theologians, educationalists and archaeologists. Its branches extended to Japan and South America.1 There are streets in several German cities (Hamburg, Kiel, Husum, Dresden, Freital, Cuxhaven, Dortmund, Berlin) named after members of the Gurlitt family, as well as an island in Hamburg’s Outer Alster Lake. Hildebrand’s father Cornelius Gustav Gurlitt (1850–1938), an art and architectural historian, was the third of seven children born to the landscape painter Louis Gurlitt and his wife Elisabeth (née Lewald). His mother Marie Gurlitt (née Gerlach, 1859–1949) was the daughter of the royal judicial advisor for Saxony, Ferdinand Heinrich Gerlach. Hildebrand Gurlitt had two elder siblings, the musicologist Wilibald Gurlitt (1889–1963) and the painter Cornelia Gurlitt (1890–1919). From 1896, the family lived in the well-located Dresden district of Südvorstadt, in Kaitzer Straße 26. In August 1923 Hildebrand Gurlitt married the dancer Helene Hanke (1895–1968). The couple had a son, Cornelius Rolf Nikolaus (1932–2014), and a daughter, Nicoline Benita Renate (1935–2012). Hildebrand Gurlitt lived and worked in Dresden (1895–1925, 1929–1931, 1942–1945), Zwickau (1925–1929), Hamburg (1931–1942), Paris (1941–1944), Aschbach (1945–1949) and Düsseldorf (1948–1956).

Museum career

Having grown up in a liberally minded household, Hildebrand Gurlitt’s view of art was predominantly influenced by his father, who was a professor of architectural history at the Königlich Technische Hochschule (royal technical college) in Dresden and an adherent of Nietzsche’s cultural critique, primarily in the popular reactionary version put forward by Julius Langbehn, a regular visitor to the Gurlitts’ house.1 Hildebrand Gurlitt engaged with Expressionism very early, in particular with works of the artists’ group ‘Die Brücke’, whose founding members were former architecture students at his father’s university. In 1906 Hildebrand, who was only 11 years old at the time, attended one of the young painters’ earliest exhibitions in a suburb of Dresden, at which his mother who was accompanying him bought two woodcuts.2 He underwent a lasting influence from his sister Cornelia, who undertook an education from 1910 at a private art school and embarked on a promising development as an Expressionist painter but took her own life in 1919.3

Hildebrand Gurlitt’s voluntary war service took him at the end of 1919 to the press department of the Ober-Ost Military Administration, where he was appointed director of the art section.4 The poets, artists, writers and journalists deployed there (including Richard Dehmel, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, Arnold Zweig and Paul Fechter) introduced him to revolutionary ideas of a new social order through questions of modern art and literature.5 In the course of his cultural propaganda work on the ground, these ideas inspired Gurlitt with a professional wish to become politically active as the director of an art museum in accordance with the new spiritual values.6 After the end of the First World War, he resumed the art history studies that he had begun in autumn 1914 in Dresden in Berlin and Frankfurt, which he completed with a doctorate in 1923.7 During his studies Gurlitt became involved in the maelstrom of museum reform, with its objective of transforming museums from elite educational venues into national education sites. The Prussian Ministry of Education and the Arts supported the movement and encouraged building collections of contemporary modern art, in particular Expressionism, which was officially regarded as a form of expression corresponding to the German national spirit as well as a mirror of the democratic system because of its diverse nature.

During the Weimar Republic, Hildebrand Gurlitt was able to demonstrate his abilities successfully on two occasions: from 1925 to 1930 he was director of the König-Albert-Museum in Zwickau and from 1931 to 1933 he was director of the Kunstverein (association for promotion of art and an exhibition venue) in Hamburg.8 In both positions he championed modern art as the vehicle for national self-assertion. To dispel misgivings about the avant-garde, Gurlitt focused his mediation concept on Emil Nolde and Ernst Barlach, who were propagandistically attributed with being close to the people as well as connected with nature and the homeland and were thus thought to build a bridge to the revolutionary world of modern German art. Notable fellow campaigners in his cause—including Edwin Redslob (1884–1973), until 1933 Imperial Art Protector [Reichskunstwart] at the Prussian Ministry of Education and the Arts, as well as Hans Posse, head of the Dresden art collections and later the first director of the Sonderauftrag Führermuseum Linz (special commission for the Führer’s museum in Linz)—attested to his having performed excellent services in developing the German museum scene.9 The strong resistance from reactionary circles could not be assuaged, however, and ultimately cost him both posts.10 Meanwhile, among his colleagues Gurlitt rapidly progressed as a ‘martyr’ for Expressionism to become one of the best-known representatives of his subject.11

Entering the art trade

After being forced to relinquish his posts, Gurlitt made a firm decision to move into the art trade. He had already been involved in some business transactions through the selling exhibitions he had organised in Zwickau and Hamburg. In parallel with this, he had assisted private individuals by giving them advice in building their collections and acquiring artworks for them. The avant-garde photography collection of the Dresden industrialist Kurt Kirchbach (1891–1967) is one of the most prominent examples. Because of his Jewish paternal grandmother, Elisabeth Lewald, Gurlitt’s attempt to establish himself officially from 1933 in the art trade did not proceed without administrative complications.1 Immediately after the transfer of power to the Nazis, Gurlitt had to prove his descent again at the promulgation of the ‘Nuremberg race laws’ in September 1935, which designated him as a ‘Mischling 2. Grades’ (second-degree ‘hybrid’, i.e. one-quarter Jewish). Nevertheless, he managed to secure and retain membership of the Reichskammer der bildenden Künste (RdbK) [Reich Chamber of the Fine Arts] for art dealers, the formal requirement for any professional activity, on account of his service in the First World War as well as his father’s good connections with high-ranking officials and the influence of his own contacts.2

After a long preamble he therefore managed to open the ‘Kunstkabinett Dr. H. Gurlitt’, his art gallery in Hamburg, on 1 November 1935.3 His works on sale ranged from German 19th-century art to the present-day, in which he obviously tried to legitimise the latest artistic trends as part of a national line of development since Romanticism. As previously, as a museum and Kunstverein director, Gurlitt proved to be a great communicator and he made his art gallery a key part of social life through countless exhibitions, lectures and evening events. According to his account books, Gurlitt repeatedly made lucrative deals with galleries in Hamburg (Commeter, Lüders), Chemnitz (Gerstenberger), Dresden (Heinrich Kühl, Emil Richter), Düsseldorf (Pfaffrath, Alex Vömel), Cologne (Heinrich Abels), Leipzig (C. G. Boerner), Mannheim (Rudolf Probst), Munich (Günther Franke, Julius Böhler) and Stuttgart (Valentien). He made especially intensive use of his Berlin contacts (Nicolai, Hans W. Lange, Matthiesen, Victor Rheins, Dr. A. Lutz, Galerie van Diemen & Co., Paul Roemer).4 These included his cousin Wolfgang Gurlitt (1888–1965), who in his youth had taken over the gallery founded by his prematurely deceased father Fritz Gurlitt 1912 to open it for the art of Expressionism.5

Hildebrand Gurlitt’s connections in museum circles, as well as in the collector scene favourable to Modernism that developed in Hamburg and Berlin, formed the basis for a firm clientele for the Hamburg art gallery. During the intensifying racist persecution, collectors of Jewish origin increasingly turned in confidence to Gurlitt to dispose of their works, as his account books and correspondence reveal. These included Elsa Helene Cohen (1874–1947), who in December 1938 sold Gurlitt some drawings by Adolph Menzel from the collection of her father Albert Martin Wolffson (1847–1913), a highly regarded Hamburg lawyer.6 Another example is the Leipzig music dealer Henri Hinrichsen (1868–1942), an acquaintance from Hildebrand’s parental home, who was murdered in 1942 at the Ausschwitz concentration camp and three years earlier had commissioned Hildebrand to sell on a part of his art collection.7 Gurlitt knew of the deliverers’ plight; he did not put forward specific details of the works’ immediate origin to potential buyers. Today these cases are undoubtedly considered to be cultural assets removed under conditions of Nazi persecution and some have been restored to their original owners.8

From 1937 Gurlitt himself came into the sights of the Nazi authorities again: after the consolidation phase of the Reichskulturkammer [Reich Chamber of Culture] and its individual chambers at the end of 1936, the measures against the avant-garde across the Reich became more radical.9 Gurlitt was increasingly being subjected to threats. In addition to initially still local Expressionists proscribed from 1933, he also showed in his Hamburg gallery artists who had already been expelled from the RdbK on the Reich’s orders (such as Emil Maetzel), or sacked from their public university posts for their views on art (such as Franz Radziwill) or were of Jewish origin (such as Anita Rée).10 When his brother Wilibald lost his professorship in musicology at Freiburg University and his family was placed under observation, he abandoned his provocative exhibition programme and signed the art gallery over to his ‘Aryan’ wife Helene.11 In this situation Hildebrand Gurlitt offered his services in October 1938 to the Reich for the ‘exploitation’ of ‘degenerate art’ in order to gain protection for himself and his family as an earner of foreign currency.12

Trade with ‘degenerate art’

From summer 1937, based on two decrees issued by the Führer, Joseph Goebbels had had over 21,000 works of modern art ‘secured’ from German museums. Some of these were sent under the ‘Entartete Kunst’ label on an exhibition tour that defamed the works on show. Others were earmarked for sale abroad in return for foreign currencies. For this the law concerning the confiscation of products of degenerate art was promulgated on 31 May 1938, by which the works were finally removed from the institutions’ assets.1 Shortly after the Berlin bookseller and art dealer Karl Buchholz, Gurlitt received the authorisation from the Fine Arts department IX of the Reichsministerium für Volksaufklärung und Propaganda (RMVP) [Reich Ministry for National Education and Propaganda] for their sale by private contract.2 Ferdinand Möller, the Berlin gallerist, and Bernhard A. Böhmer, the sculptor and former manager of the recently deceased Ernst Barlach in Güstrow, were also brought in. In comparison to his three colleagues, Hildebrand Gurlitt took on the most works from the confiscated assets: Gurlitt (3,879), Möller (848), Buchholz (883) and Böhmer (1,187).3 Gurlitt primarily traded with his Swiss contacts; however, he also paid French Francs and English pounds for his transactions into the special accounts designated for this purpose.4

The contact for the art dealers was the doctor of law and art historian Rolf Hetsch (1903–1946), who had compiled the inventory for the confiscation. Since autumn 1937 as an expert he had been responsible for ‘degenerate art’ matters first in the RdbK and later in department IX of the RMVP.5 Hetsch was a cousin of Adolf Ziegler (1892–1959), who had been appointed by Goebbels as President of the RdbK at the end of 1936 and in summer 1937 as head of the committee for the confiscation of ‘degenerate art’. Gurlitt and Hetsch had known each other before this period through their respective connections with the Kunstdienst der evangelischen Kirche [art association of the Protestant church], founded in 1928 by the book dealer Gotthold Schneider (1899–1975) in Dresden. The Kunstdienst considered what had become burning questions relating to modern church architecture and church art. Many of its members came from Hildebrand’s father Cornelius Gustav Gurlitt’s circle of acquaintances.6 As director of the Hamburg Kunstverein, Hildebrand had taken over the ‘Kult und Form’ exhibition organised by the Kunstdienst to open his winter 1931/1932 programme and for the first time published a catalogue for the exhibition.7 Together with the Kunstdienst, Gurlitt is said to have counteracted the rightward lurch proceeding from the Kampfbund für deutsche Kultur [combat league for German culture] and the outright condemnation of modern art that accompanied it.8

In 1933, having successfully organised together with Rolf Hetsch on Goebbels’ orders the German church art section at the Universal Exhibition in Chicago in 1933/1934, the Kunstdienst had been relocated to Berlin and firmly incorporated into the RdbK. Ernst Barlach and Emil Nolde, whose works featured at the Universal Exhibition, were appointed to the Kunstdienst’s honorary committee. Goebbels himself had made positive comments about both artists in the 1920s and owned two sculptures by Barlach.9 Entirely in the spirit of Gurlitt’s own ambitions, the Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Studentenbund (NSDStb) [Nazi German students’ association], which was close to Goebbels, saw both these Expressionist masters as path-finders for the new Germany. Accordingly, the Kunstdienst campaigned for Nolde’s official appointment as state artist.10 In the context of the debate about Expressionism emerging from these ranks, advocates of the style right up until 1935 were able to promote their favourite painters and sculptors through various fora.11 Alfred Rosenberg reprimanded his rival Goebbels for supporting the movement by appointing people to posts in the RdbK, ‘who are on the very closest terms with the Barlach–Nolde circle’, by which he meant the Kunstdienst.12

In addition to Rolf Hetsch, Gurlitt’s personal contacts with the Kunstdienst staff can be proven in the cases of Gotthold Schneider and Stephan Hirzel (1899–1970). Hirzel was a co-founder of the Kunstdienst. Gurlitt had met him at the latest in 1925, when he included him in one of his earliest exhibitions at the König-Albert-Museum in Zwickau13. In 1931 Hirzel was promoted to be deputy director of the Kunstdienst. He also participated directly in 1933 at the Universal Exhibition in Chicago; in the same year he was assigned the executive editorship of the RdbK’s publication Die Kunstkammer, one year later the report of the Reichspressekammer (Reich Media Chamber). In that sense Gurlitt already maintained informal contacts with the Goebbels faction at this early stage. The relations intensified when in summer 1938 the Kunstdienst took the part of the ‘degenerate art’ categorised as ‘internationally exploitable’ to Schloss Schönhausen, which it was using in North Berlin, and in close consultation with Hetsch participated in the organisation of the ‘exploitation’.14 When shortly afterwards—in August 1938—Ernst Barlach died, a clandestine Estate committee to look after his art, to which Rolf Hetsch belonged, was established at his residence in Güstrow, as he was supposedly empowered by his post in the RMVP to subvert the artist’s official proscription.15

The committee’s regular meetings, some of which took place in the Berlin office of the Kunstdienst in Matthäikirchplatz, went far beyond the Barlach matters. When in early 1943 Goebbels declared ‘total war’, Hetsch and Bernhard A. Böhmer, who also belonged to the committee, organised the evacuation of the remainder of the ‘degenerate art’ to Güstrow.16 After the end of the Second World War the idea of ‘Nordic Expressionism’17 was to be revived here. The artists’ colonies in Worpswede and Fischerhude in Lower Saxony, with which Hetsch nurtured close contacts over the years, were considered to be counterparts to Güstrow.18 Amplified by Emil Nolde in Seebüll, the future vision of a cultural triangle of national revolution-minded and active artists in Northern Germany had arisen. To fulfil the plan, at the end of 1943 the Kunstdienst obtained a property there initially intended for Joseph Goebbels, which demonstrated that Gurlitt was part of a network that regarded a part of aesthetic modernity as compatible with the RMVP’s cultural ideology.

Networks in the Occupied western zones

Gurlitt’s strong connections with the RMVP also helped him in expanding his business dealings to the occupied western zones. From November 1940 at the latest he maintained trading connections with Holland and Belgium and had an interest in this for the Reich confirmed by Hetsch.1 Two months earlier Eduard Plietzsch (1886–1961) had been appointed as art expert for the Mühlmann agency in The Hague. Gurlitt and Plietzsch had known each other since the early 1920s. Initially assisting Wilhelm von Bode and Max J. Friedländer in the Berlin Museums, in 1919 Plietzsch had joined the van Diemen & Co gallery of the Markgraf-Konzern, soon afterwards taking over as director. Wilhelm von Bode’s great nephew Leopold Reidemeister (1900–1987), Gurlitt’s fellow student in Berlin and lifelong friend, had worked for Plietzsch as a student employee and introduced Gurlitt into gallery circles. Plietzsch had specialised in the Dutch painting of the 16th and 17th centuries; like Gurlitt and Reidemeister he had a predilection for Expressionist art. In Gurlitt’s account books there are provable transactions with Plietzsch between March 1938 and February 1941, mainly for works by international turn-of-century Modernists (such as Ferdinand Hodler, Édouard Manet, Edvard Munch, Auguste Renoir and Paul Signac).2

One month after his trade with ‘degenerate art’ petered out with the end of the Nazi campaign on 30 June 1941, Gurlitt made his first trip to Paris at the RMVP’s behest in order to assess the French art market and purchase works for German museums.3 Up to July 1944, he is thought to have stayed in the French capital on 31 further occasions in order to keep expanding his business and finally to work on the ‘Sonderauftrag Führermuseum Linz’. His trade in the service of the Reich, which he had entered at home for the protection of his family, thereby continued uninterrupted. His point of contact in Paris was the Deutsche Institut (DI), the cultural section of the German embassy, where he obtained his travel visa and the expert reports required to sell on the works he had acquired.4 Simultaneously Gurlitt worked on propaganda for the Institute and tried to build up ‘the greatest sympathy’ with ‘French artists’ circles’.5

The DI had been established by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Following the Occupation of France, the Reich Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop had despatched a task force of his special advisors on France to the agencies of the Military Commander [Militärbefehlshaber] in France to represent the interests of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Otto Abetz led the group that created the concept of the DI, whose members included Rudolf Schleier and Karl Epting.6 Shortly afterwards, Abetz was appointed as the German ambassador, Schleier as the envoy, and Epting became director of the DI. From the outset Goebbels had tried to orientate the new institution’s activities along the RMVP’s lines. He was also the person who most vehemently advanced the ‘retrieval’ of German cultural assets from the western federal states and furthermore secured ‘art property from Jewish and anti-German owners’7 to the benefit of German museums in compensation for destroyed assets. For this Goebbels had been commissioned by Adolf Hitler with the central management. For the preparatory stage he had brought in Adolf Ziegler and Rolf Hetsch, while the execution fell to Abetz, Epting and Schleier.8

Hildebrand Gurlitt later remembered some important works from the Rothschild collection that he thought he had seen at the German embassy: a baroque writing-desk that Abetz used, as well as some important French 18th-century drawings.9 The decree of 6 November 1940 enabled the Military Administration to put an end to these large-scale operations. However, Goebbels still managed to exert his influence through the Kunstdienst staff. Otto Abetz himself had belonged since 1937 to the Kunstdienst; later he became its chairman. Hildebrand Gurlitt’s long-standing acquaintance Stephan Hirzel organised the DI’s art and theatre programme, for which Gurlitt also submitted proposals.10 Rolf Hetsch also worked as exhibition organiser for the Kunstdienst in the DI’s propaganda work. One of the major projects was the Arno Breker retrospective organised in autumn 1942 by the Kunstdienst and the DI at the Orangerie in Paris. The artist had in fact previously joined the Kunstdienst by the mediation of Abetz.

On account of his various tasks, Hirzel only ever spent one week a month in Paris. Nevertheless, he was also involved in the art trade on the ground, albeit only ‘semi-officially’,11 which is why the Kunstdienst activities in Paris are difficult to reconstruct and have not previously been the object of research. Through its subsequent inquiries the Monuments, Fine Arts and Archives section received some indications of a clandestine RMVP network that used an art storehouse, available to both the Wallraf-Richartz-Museum and the Cologne Kunstverein, at Burg Nideggen near the border with the occupied western zones:

‘There existed an extensive and well-knit underground network of professional artists and architects who watched, and made an effort to control, the disposition of art which was condemned, confiscated, appropriated, or which generally changed hands. Some of these men worked clandestinely in the Propagandaministerium for the express purposes of observing and ‘changing labels of art marked for disposal’.12

The people listed in the document belonged either to the Kunstdienst or to Güstrow circles: Hugo Körtzinger, Bernhard A. Böhmer, Otto Andreas Schreiber, Carl Georg Heise, Otto Bartning, Stephan Hirzel and Gotthold Schneider.13 Here the distribution routes of ‘degenerate art’ and works from France seem to intersect, with works possibly being smuggled back into the art trade under new labelling.

In 1942 Goebbels had to provide an official justification of his collaboration with the Kunstdienst. In the wake of Rosenberg’s above-described criticisms, in 1941 Reinhard Heydrich, Head of the Security Service for the surveillance of opposition movements, had criticised Goebbels for his free handling of the ‘exploitation’ of ‘degenerate art’ as an ‘extraordinarily serious sabotage of the Führer’s art policies’.14 In the investigation that ensued, the Kunstdienst was again blamed for following ‘cultural bolshevist trends’. The inclusion of unwelcome literature and politically undesirable scientists in the DI’s cultural programme was also discovered.15 Otto Abetz and his Paris staff at the DI then had to pull out of France at the end of 1942. However, Goebbels knew how to push through his interests and reposition his people in the posts that mattered to him. In February 1943 Abetz was able to return to the embassy in Paris; Epting followed somewhat later. Ultimately the events strengthened the Kunstdienst more than they damaged it. Goebbels suddenly transferred the RdbK staff directly into the Fine Arts department IX of the Propaganda Ministry. The Kunstdienst therefore drew closer together with Rolf Hetsch, who had since been appointed as the department’s senior government advisor[Oberregierungsrat] and thus could extend his powers.16

Trading partners and acquisition strategies

Gurlitt’s networks in Paris developed out of the interconnecting structures of the German embassy and the DI. Gurlitt dealt directly with Abetz and Epting. He maintained especially close contact with Rudolf Schleier. ‘By enabling me to work in Paris, you have done me a service that is decisive for my life’, Gurlitt assured the envoy in a letter of February 1942.1 Together with his friend Hans Domizlaff (1892–1971), a well-known advertising expert, who had also been staying in Paris on business since late summer 1941, he obtained Schleier’s support for the painter they admired, Marie Laurencin, who was being criticised in Germany for having helped her husband to desert during the First World War and whose works were considered ‘degenerate’ from 1937.2 Gurlitt provably delivered artworks to Schleier, as well as to Abetz and Epting.3 Later Gurlitt swore under oath that Schleier, who had to answer in the context of the Nuremberg trials for his involvement in anti-Jewish campaigns outside Germany, had saved him from forced labour by repeatedly issuing a visa. Gurlitt also confirmed Schleier’s statement that he had not bought any artworks of Jewish ownership for his own collection.4

One of the intermediaries who belonged to these networks, Adolf Wüster, played a path-breaking role for Gurlitt in Paris. According to Gurlitt, Wüster was widely known as the principal buyer, agent and advisor for German museums.5 His business deals were concentrated on Rhineland museums, in particular the Cologne institutions with which Rudolf Schleier also maintained close connections.6 Wüster’s most important Paris business partners included Hugo Engel (a Jewish-Austrian gallerist in Paris), Victor Mandl, Martin Fabiani, Raphaël Gérad, Gustav Rochlitz, Erhard Göpel, Rudolf Melander Holzapfel, George Terrisse and Theo Herrmsen. Gurlitt trod exactly the same pathways in the French art market,7 with the contact with Göpel having occurred earlier, probably through Plietzsch, who also traded with Rochlitz and Holzapfel.8 Furthermore, Gurlitt’s purchases at the Hôtel Drouot are well-known. Gurlitt maintained a direct connection with the auctioneers Etienne Ader and Fernand Lair-Dubreuil, as well as with the expert at the Hôtel Drouot, André Schoeller, a close friend of Wüster.9 Schoeller was regarded as a specialist in French 19th-century art and he operated as an important deliverer for Gurlitt. Gurlitt’s literary estate contains over one hundred expert reports issued by Schoeller.10

By far most of Gurlitt’s trade was undertaken with Theo Hermsen. The art dealer from The Hague moved to Paris in 1939 and lived in the ninth arrondissement (Rue de la Grange-Batelière), close to the Hôtel Drouot. According to Gurlitt’s account books, Hermsen’s earliest acquisitions from Hermsen took place in August 1942. In the same month Adolf Wüster had been granted the title of consul by Hitler. For his new task as academic employee of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, to furnish the ambassador’s and envoy’s rooms with artworks, he could now operate very flexibly at the administrative level with extended decision-making powers, but he was not simultaneously allowed to act as a dealer.11 This is probably how Gurlitt will have taken Wüster’s place in his trades with Hermsen: in his very first transaction of 3 August 1942 Gurlitt took over from Hermsen at one stroke 38 works for a lump sum of 41.000 + 4.000 RM; only five days later he delivered 30 of them, shortly afterwards the remainder. All the works went to Cologne, most of them to the Kunstverein, one to the Wallraf-Richartz-Museum and six to a private collector.12 The painter Lucien Adrion,13 by whom Rolf Hetsch owned at least two paintings, was closely involved in Gurlitt’s trading with Hermsen.14

Until 1944, Hermsen remained the principal source for Gurlitt. At least 80 per cent of the objects he acquired in the occupied western zones (primarily paintings by French artists, but also tapestries), which can be reconstructed from the account books and foreign currency certificates, went on to the Dutchman’s account. Hermsen, who spoke German, and had specialised in the delivery of French works to German museums, offered as a special service the procurement of the necessary export licences from the Kunstschutz, by which some of the deliveries to Germany were organised as ‘military transport on the orders of the propaganda team in Paris’.15 Supposedly Hermsen also met the costs of this even when the trades foundered, in which case he was to have taken back the works. Hermsen is also very likely to have been the ‘Paris business friend’ who regularly paid Gurlitt’s hotel costs on account of the profitable business transactions ‘over very large sums’.16

Gurlitt was easily able to step into Wüster’s shoes. After his move into the art trade from 1933 he had continued to maintain the connections with the German museum scene, which then opened doors for him across the country. His incompletely transmitted correspondences from the 1942 to 1944 period contain discussion of offers to the museums in Breslau, Dortmund, Dresden, Düsseldorf, Erfurt, Frankfurt, Hamburg, Lübeck, Königsberg, Mannheim, Munich, Nuremberg, Oldenburg, Weimar and Wiesbaden. Like Wüster before him, Gurlitt also formed with Cologne in particular one of the most enduring commercial relationships. As a dealer in ‘degenerate art’ he was able in close consultation with Otto Förster, the director of the Wallraf-Richartz-Museum, to obtain exchange deals from the RMVP that were lucrative for both sides, although they contravened the officially established trade regulations.17 Gurlitt built on this relationship of trust. On his journeys from Hamburg or Dresden to Paris he made a stop almost every time in Cologne. Contemporary research has shown that Gurlitt delivered to the Wallraf-Richartz-Museum during the Occupation period 27 high-quality works from France, comprising 54 percent of the purchases sourced from there during this period.18

For the Wallraf-Richartz-Museum Gurlitt did not deal only with Förster. He was also in lively contact with the head of the Graphics Collection, Helmut May (1906–1993), as well as Fritz Fremersdorfer (1894–1983), curator of the Roman–Germanic department.19 By far most of the works from France delivered by Gurlitt went to the Cologne Kunstverein, as can be deduced from the above-mentioned transaction of 3 August 1942. In total 110 objects are listed in Gurlitt’s account books.20 The Cologne Kunstvereinrepresented the same trend as Hildebrand Gurlitt and in the Expressionism debate kindled in 1933 it adopted a position in favour of modern art. In the context of the exhibition series initiated for this, ‘Neue deutsche Malerei’ [new German painting], in 1934 Gurlitt was able to accommodate his own watercolour collection of works predominantly by Dresden artists.21 From early 1942 Otto Förster’s son-in-law, Toni Feldenkirchen, headed the Kunstverein. With him, Gurlitt continued his good relations with both his predecessors, Walter Klug and Hans Peters. Gurlitt’s extensive sales to the Kunstverein included works by such renowned masters as Edgar Degas, Renoir, Signac and Auguste Rodin, but also works by unknown artists such as Paraire, [Ernest-Victor ?] Hareux, Lévigne, and [Jacques Alfred ?] Brielman.22 The question remains as to how a Kunstverein—with its goal of furthering the contemporary art of its region by exhibitions and other events rather than build a collection of its own—was drawn into the trade and what happened to the remaining pictures that were withheld by the Allies.

In addition to his trades with German museums, Hildebrand Gurlitt also acquired artworks in the occupied western zones for private collectors and gallerists. His clients belonged to the circles of friends and dealers in modern art that he had established long before in his places of activity in Germany. These included the Zittau-based textiles manufacturer Carl Neumann (1896–1966), for whom he acquired the painting Vallée l’Arc et Mont St. Victoire that was thought to be by Paul Cézanne from the Viau auction at the Hôtel Drouot in December 1942, which later turned out to be a forgery.23 Most of the works were delivered by Gurlitt to Hermann F. Reemtsma (1892–1961), the Hamburg cigarette manufacturer, who on account of his affinity with Barlach was closely involved in the Kunstdienst activities in Güstrow and had maintained constant contact with Gurlitt since the early 1930s. In Cologne as well, Gurlitt had a loyal clientele for his purchases in Paris: foremost among these was the lawyer Josef Haubrich (1889–1961), to whom Gurlitt had previously sold countless ‘degenerate art’ works, which in 1946 could then be made available again to the public with his bequest to the city of Cologne.24

With regard to Gurlitt’s continued transactions with German trading partners after 1941 reference should be made to Heinrich Kühl and Paul Rusch in Dresden, Alex Vömel and the Galerie Paffrath in Düsseldorf, Galerie Commeter in Hamburg and Julius Böhler Jr. in Munich. Remarkably frequently Gurlitt served his Berlin colleagues, such as Arnold Blumenreich, Victor Rheins, Galerie Matthiesen, Friedrich August Lutz (a former colleague of Eduard Plietzsch at the Galerie van Diemen & Co) or Hans W. Lange. Hildebrand’s cousin Wolfgang was also one of his customers for French works in the Reich capital, as well as Bernhard A. Böhmer, who in addition to Güstrow had business premises at Tiergartenstraße 28 in Berlin.25 Gurlitt developed a new and almost friendly connection with Paul Römer, who previously worked in Heinrich Thannhauser’s gallery in Munich and ran a branch in Berlin with his son Justin K. Thannhauser from 1927. As a result of Justin Thannhauser’s escape to Paris, Römer took over the business on Lützowplatz in December 1937 and when because of the German Occupation Thannhauser had to emigrate in 1940 through Switzerland to the USA, Gurlitt became the most important supplier of French works for Römer.26

The Special Commission: Sonderauftrag Führermuseum Linz

Officially Gurlitt could only buy artworks in France for private individuals until December 1942; afterwards the foreign currencies required for this were barred to him because of a new decree concerning goods traffic.1 Very soon, however, he received a far more lucrative assignment. When the Wiesbaden Museum director Hermann Voss was appointed in March 1943 by Joseph Goebbels as Hans Posse’s successor and he took over the Special Commission for the planned Führermuseum in Linz, he chose Hildebrand Gurlitt as ‘chief buyer’ in Paris. They had probably already got to know each other in the 1920s through Eduard Plietzsch, with whom Voss had worked at the Berlin Museums. The connection between Gurlitt and Voss must have been very trusting: Gurlitt later stated to the Allies that he had worked from 16 February 1943 for Voss and the Special Commission.2 Actually it was not until the evening on this date that the decisive conversation between Hitler and Voss took place that was known to only a few people other than Goebbels. Voss must then have reported this to Gurlitt without hesitation and engaged him as a dealer, before the old structures established under Posse were dissolved.

Gurlitt’s involvement in the Special Commission was almost certainly favoured by Goebbels’ reinstatement of his contacts in the German embassy and the DI at the beginning of 1943.3 He explained to officials that he would from then on be constantly resident in Paris for the German embassy and the Military Commander.4 At around this time—even before his firm collaboration under Voss—Gurlitt gained the first opportunity to work for the ‘Special Commission’. The art historian Erhard Göpel—from May 1942 posted to The Hague with the Reich Commissar Arthur Seyß-Inquart in the occupied Dutch regions in the Referat Sonderfragen, the department responsible for special questions concerning the procurement of artworks for the planned Führermuseum—had involved Gurlitt by January 1943 at the latest in these purchases.5 Göpel held Gurlitt’s connoisseurship in high esteem. He knew about his connections with Eduard Plietzsch at the Mühlmann agency and successfully campaigned for an expansion of Gurlitt’s activities in Holland and Belgium.6 Göpel himself worked for the Mühlmann agency as an external art dealer, as did Max J. Friedländer, whom Eduard Plietzsch and Hermann Voss had assisted at the Royal Prussian art collections under the general direction of Wilhelm von Bode and whom Hildebrand Gurlitt had known personally since his time in Zwickau.7 Göpel involved a remarkably large number of colleagues of Jewish origin in his services, for which he later had to answer to Seyß-Inquart.8

With his involvement in the Special Commission for the Führermuseum in Linz, Gurlitt’s income soared. He admitted to the public prosecutor for the state of Bamberg after the end of the Second World War in his de-Nazification trial having earned in his first two years in Paris 44,452 and 41,001 RM respectively.9 That would already have been over double the amount in the previous period as a dealer in ‘degenerate art’.10 In 1943 and 1944 the sum reportedly multiplied to 176,855 and 159,599 RM respectively.11 The figures given by Gurlitt are far from reliable though; he himself admitted that he had only made the statements from memory.12 According to the extant foreign currency certificates, in January and February 1944 he paid out foreign currencies amounting to 684,000 RM for his purchases from Theo Hermsen and Gustav Rochlitz13. In the four following months, from March to June, he acquired a total of 69 paintings, ten tapestries and 82 drawings to the equivalent value of 3,612,000 RM for the ‘Special Commission’. In July 1944 he was able to conclude a top-ranking deal with six tapestries and three paintings for an approximately similar high sum of 3,130,000 RM. Still in August 1944—shortly before the Allies liberated Paris—Gurlitt purchased works there for 610,000 RM, but then had to try to have these transported into the Reich via Brussels.14

Gurlitt received for his purchases five percent of the total price of the artworks as commission from the funds of the ‘Special Commission’.15 On that basis a sum of 401,800 RM can be calculated with reference to the above-mentioned purchases for January to August 1944, with the documents for this period indicating a further profit of 6,000 RM in favour of Hildebrand Gurlitt.16 After the French art market was finally barred to him, he postponed his trade journeys into Hungary that was allied with Germany and received in October 1944 foreign currencies to an equivalent value of 500,000 RM.17 Some of Gurlitt’s transactions were directly processed through the special accounts of the ‘Special Commission’. However he also ordered foreign currencies in the name of his own art dealing business. In these cases Gurlitt purchased the works directly into France and sold them on in Germany to the ‘Special Commission’. The cash flows ran through both the Wilhelm Rée bank in Hamburg, which granted him a cash loan in the amount of 200,000 RM, and the Dresdner Bank, where he had a loan account. In the Paris office of the Dresdner Bank on the Avenue de l’Opéra, the foreign currencies were made available to him.18 In this way, the profit margin between purchase and sale consisted solely in Gurlitt’s judgement and negotiating skill.19

Also in the context of the ‘Special Commission’, Gurlitt bought by far the most works for German museums, albeit only 168 works in total specifically for the Führermuseum in Linz, which alone would scarcely have merited his status as ‘Chief Dealer’.20 The furtherance of German museums by the ‘Special Commission’ was expressly intended and gained importance above all under Voss’s direction, as it was also in Goebbels’ interest. Gurlitt therefore had no difficulties at all obtaining foreign currencies in a large quantity. The certificates first had to be approved by the RdbK, after which the documents were issued by the Reichsstelle für Papier.21 Gurlitt repeatedly gave Rolf Hetsch’s name as a person of reference. This connection is probably the explanation for Gurlitt’s statement to Rudolf Schleier: ‘I was able to achieve a number of things for Cologne and other museums’.22

According to Michel Martin, the Louvre curator responsible for export licences, Gurlitt bought artworks in Paris for a total of ‘400 to 500 million francs’.23 Just half of this amount he used for purchases in the context of the ‘Special Commission’ for the Führermuseum in Linz and other German museums. Approximately 350 of these works remained in Gurlitt’s possession and resurfaced in 2012 with the ‘Schwabinger Kunstfund’24. Exactly how many works Gurlitt acquired in France is however almost impossible to calculate. Gurlitt admitted to the Allies only a fraction of the works that he actually delivered.25 Many transactions are undocumented. A further difficulty is that Gurlitt made his foreign currency account available to third parties such as Erhard Göpel26 and the trade contacts of the Roman–Germanic department at the Wallraf-Richartz-Museum.27 Moreover, the statements in the various archive documents do not tally with those in Gurlitt’s correspondences and account books. The origin of the works is equally difficult to reconstruct because of the intermediary dealers. Furthermore, Gurlitt had some false receipts issued to disguise the actual sellers, as with the Vienna restorer Jean (Hans Wilhelm) Lenthal for his purchase of 41 paintings by French artists on 20 June 1942.28

Arrest in Aschbach and de-Nazification

The heavy air raids on Dresden from 13 to 15 February 1945 destroyed Hildebrand Gurlitt’s parental home, into which he had moved back with his family at the beginning of 1942, after an aircraft bomb had seriously damaged the building of his flat in Hamburg. In March 1945 he fled with this wife and the two children from Dresden to Baron Gerhard Freiherr von Pölnitz’s estate in Aschbach in the state of Bamberg, which was considered a safe haven from bombing. In May that year Karl Haberstock and his wife also found refuge there. Von Pölnitz, a Luftwaffe officer stationed in Paris during the Occupation, organised transport possibilities for the removal of works acquired in France. Also, he had appeared as a representative for Hugo Engel’s gallery in Germany and had concluded trade deals mainly with Haberstock and occasionally with Gurlitt.1

On 10 June 1945 Gurlitt was interrogated by First Lieutenant Dwight McKay, Judge Advocate Section, Third U.S. Army, and placed under arrest along with his family at Schloss Aschbach.2 On 3 October that year the second interrogation ensued by the staff of the Art Looting Investigation Unit (ALIU) concerning his involvement in the Führermuseum Linz Special Commission.3 During his escape Gurlitt had delivered several crates with parts of his art collection to Aschbach. For the verification of the works, the crates of pictures were brought in December 1945 to the Central Collecting Point at Wiesbaden. Further individual works and packages of graphic works that Gurlitt also declared as his own collection remained secured in Aschbach.4 In the following two years, intensive interrogations took place concerning Gurlitt’s trade contacts, the origin of the works and prices paid. In addition to this, Gurlitt had to compile a list of the works he had sold to German museums and private collectors from the occupied regions as well as deliver to Munich the Max Liebermann works still stored in Aschbach that he had purchased from Hermsen in Paris.

In parallel with this, the Bamberg state Spruchkammer (de-Nazification chamber) began investigations into Gurlitt’s relations with the Nazi party and the extent of his profiteering from the Nazi system. On account of his advocacy of the art condemned by the Nazis as ‘degenerate’, as well as above all on account of the discrimination as a ‘Vierteljude’ (one-quarter Jew), Gurlitt was able to present himself convincingly as a victim of the Nazi regime.5 He said he had worked for the ‘Special Commission’ to protect himself from persecution and arrest in Germany by the repeated absences that were necessary for the journeys.6 He had never been a party member,7 (although this would not have been possible on account of his descent). Accordingly, Gurlitt emerged from the trial in July 1947 as an ‘Entlasteter’ (an exonerated person).8 It turned out, however, from further enquiries to the relevant Finance Office that Gurlitt had stated far too low a figure for his annual income from 1941 to 1945. Spurred on by the denunciation of a former colleague at the Hamburg art gallery, the public prosecutor resumed the proceedings and accused Gurlitt of profiteering from the Nazi system [Nutznießerschaft].9

Although Gurlitt’s income had far exceeded the permissible level of 36,000 RM per annum, he was able to avoid a sentence on this occasion as well.10 With the submission of numerous character references, the Spruchkammer accepted Gurlitt’s argument that he had obtained the increase in his income solely on the basis of his knowledge of art and high professional skill.11 He had not thereby profited from the political system, according to the Spruchkammer in its second judgement of 12 January 1948,12 and although his statements over the course of time concerning the origin of the secured works displayed considerable discrepancies, in December 1950 his collection was made available in Wiesbaden.13 Meanwhile at the beginning of 1948 Gurlitt had been appointed director of the Kunstverein for the Rhineland and Westphalia and had moved with his family to Düsseldorf.14 Otto Förster of the Wallraf-Richartz-Museum had recommended him for the post. Gurlitt’s long-standing friend Leopold Reidemeister took over the direction in 1946, and in 1954 the general management of the Städtische Kölner Museen. With Joseph Haubrich’s bequest of his collection of predominantly Expressionist works, Cologne advanced to become the capital of the formerly proscribed art, whereas other cities had to complain for a long time later about the gaps caused by the confiscation. Thus Gurlitt was easily able through his old networks to reconnect with his endeavours of the Weimar period.

Hildebrand Gurlitt died on 9 November 1956 in Oberhausen.