Lootings and restitutions in libraries

One day, someone will tell the story of the regrettable odyssey of these books, cubic meters of them, torn from schoolchildren, teachers, professors and booklovers all over France. The most exquisite masterpieces, the rarest editions, seized & thrown in along with detective novels and textbooks […] A book from the Bibliothèque rose with a dedication to a little French girl on her birthday and found in a castle in Germany looks up at you with more sadness, perhaps, than any other.”

Preface, Manuscrits et livres précieux retrouvés en Allemagne. Exhibit organized by the Commission de récuperation artistique, Bibliothèque nationale, 1949.

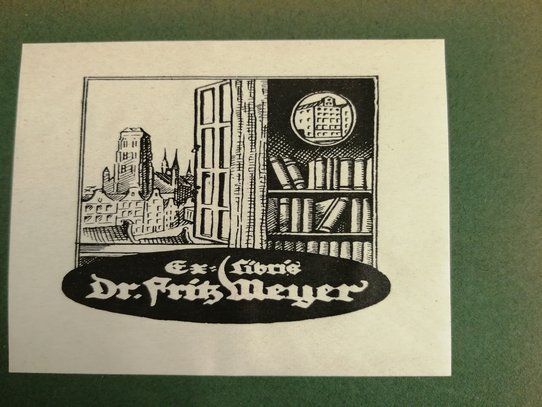

Although the Nazi looting of artworks has more or less lived on in the collective memory, the same cannot be said for the massive plundering of private libraries. And for several reasons: unlike the work of art that belongs to a single individual, books most often belong to the multiple; a book is only unique when it takes on the shape of a manuscript, an autograph, antique book or unique archive. Yet millions of books, the ordinary like the rare and precious, were seized by the Nazis in all the occupied countries, transported to Germany or abandoned in depots after continual sorting.

No one knows how many books were seized in France. In 1949, the Répertoire des archives, manuscrits et livres rares estimated the number at 20 million.1 Since this figure includes archives, we can rely on the estimations of the librarian Jenny Delsaux (1896-1977), responsible for the sub-committee of books of the Commission de récuperation artistique at the Liberation,2 according to whom the 2 million books that were found would only be “20%” of the thefts. In other words, perhaps 10 million, and with certainty, at least 5 million books were violently seized from their legitimate owners.3

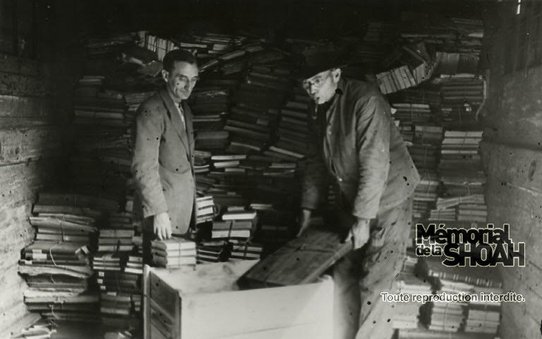

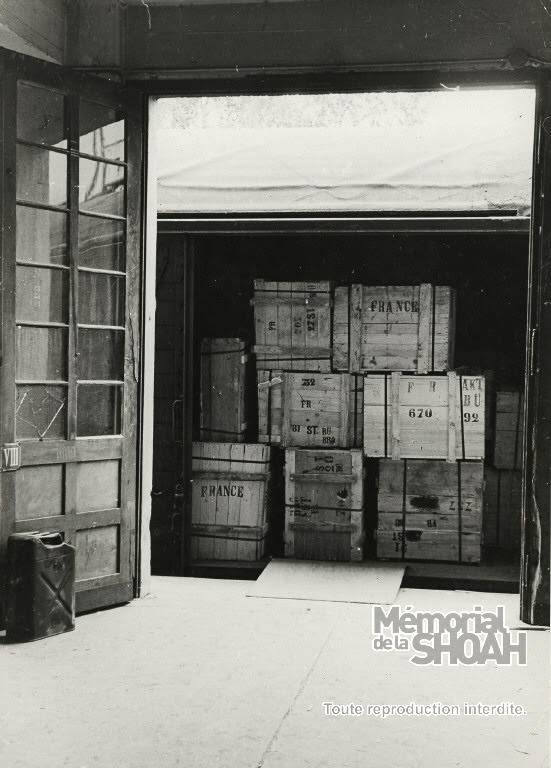

Source : Published with the consent of Archives du Mémorial de la Shoah, CIII_28_4.

Source : Published with the consent of Archives du Mémorial de la Shoah, CIII_28_5.

Premeditated and planned operations

Thanks to their agents, sometimes to their researchers, scientists, historians, art historians and/or curators, archivists and librarians sent to France, the Nazis had long put a finger on collections and archives they considered as belonging to them. Long before 1939, they had a thorough knowledge of the great Jewish, masonic, Russian and Polish libraries in France, and during the war, added to it according to demand. They knew exactly what they wanted, and confiscation owed nothing to chance.

Seizures: three rationales, three temporalities

Even more than the seizure of artworks, the looting of libraries was the product of three rationales: war, nationalist, and anti-Semitic.

Lootings carried out on a war rationale, considering the horror of other Nazi lootings, seem “usual” in a number of wars. As of June 1940, the occupiers seized documents they considered their property because they had been stolen by France between the 15th and 20th centuries, because they concerned the history of Germany or belonged to German anti-Nazi émigrés. Archives and public documents liable to house “State secrets” were seized, such as the archives and sometimes the libraries of strategic ministries (War, Interior, Foreign Affairs,1 etc). The war rationale also justified seizures and acts of violence towards French personalities known to be anti-Nazi, towards institutions of freemasonry and individual freemasons, hated more for their commitment to the Republic and to the traditions of the Enlightenment than for the rites and secret powers often denounced.

The second rationale is in keeping with an expansionist nationalism, to which the Third Reich gave a specific meaning with its determination to eradicate cultures and populations, Germanize and Nazify them: hence the annexation of Alsace and Moselle. During the summer of 1940, community libraries created by émigrés from central Europe in the 19th century – Polish, Russian (Tourgueniev), Ukrainian (Petlioura) etc – were sent to Germany.

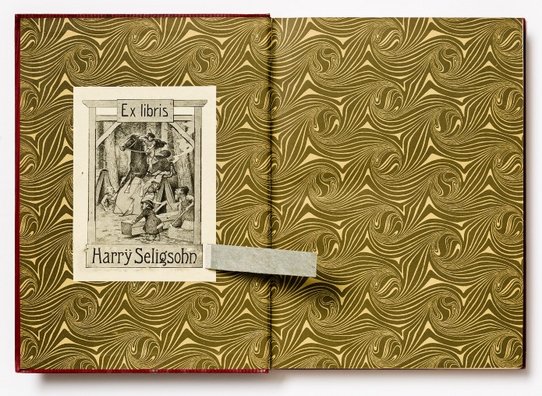

The third rationale was specific to the Nazi regime: antisemitism accounts for the major part of abuses suffered by libraries. As of the summer of 1940 again, the large Jewish community libraries were seized (Alliance israélite universelle, [Vladimir] Medem, etc), as were the art collections and libraries of well-off Jewish families – those of the Rothchilds, for example, whose three Parisian branches (Édouard, Robert, Edmond) possessed written works “patiently gathered, that included tens of thousands of antique books and precious bindings, let alone a rich Jewish library.”2 As the war went on, lootings became more systematic and more anonymous: beginning in mid-1942 they targeted the tens of thousands of hunted down, hidden, imprisoned and deported Jewish families, whose possessions were seized and often small libraries transported to Germany or abandoned in storage places in France to be continually sorted. The destruction of these thousands of libraries was not in keeping with any strategy to enrich German libraries, only with the will to destroy the very memory of a culture, to accomplish the physical elimination of persons together with the symbolic murder of the mind.

As with the looting of artworks, the actors involved in plundering libraries were numerous and sometimes in competition amongst themselves or with the Vichy regime: the embassy of Otto Abetz, the army commandos during the invasion, the Wehrmacht, the Gestapo, and above all, the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg (ERR), which rapidly became the all-powerful organizer – the Reichsleiter Alfred Rosenberg was charged by Hitler with transporting precious objects to Germany and putting them “in a safe place.” In mid-1942 the ERR became the Möbel Aktion (“Furniture operation”).

Source : Bibliothèque de l'Institut national d'histoire de l'art (INHA), BCMN collections, 8 F 0147 to 8 F 0152. Documents looted during the Second World War, purchased by the Bibliothèque des musées nationaux from the Domaines in 1951.

The dispossessed

The possession of a large, specialized library, evidence of the owner’s sustained interest in a field, explains the high rate of individuals in intellectual and artistic professions claiming restitution. However, the libraries of doctors, lawyers, scientists and artisans having a professional need for books, were also among those seized. In fact, the size of a library was inversely proportional to the number of despoiled persons: the immense majority of persecuted Jewish families possessed small libraries.

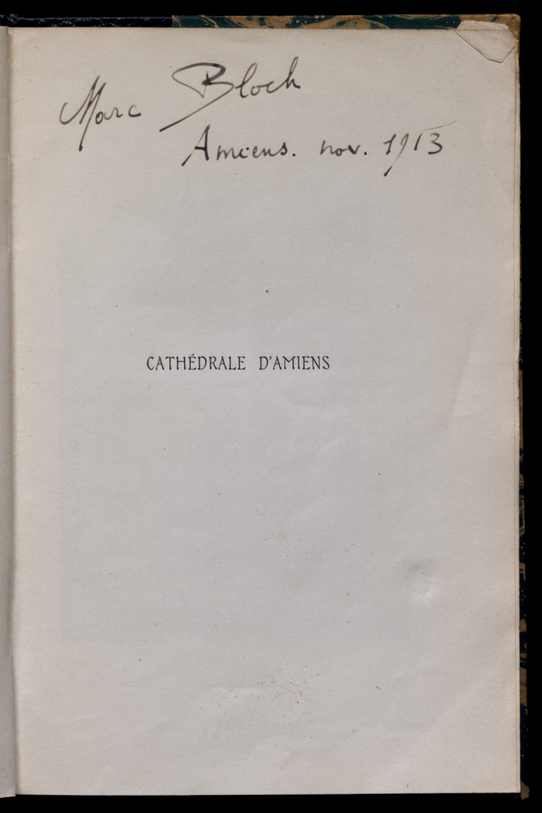

Many were university professors and administrators: Paul Léon, administrative director of the Beaux-Arts, professor of art history at the Collège de France, Maurice Halbwachs, sociologist, who died in Buchenwald, and Edmond Vermeil, professor of Indian studies; Léon Brunschvicg, Sorbonne professor who died after being pursued in 1944, Louis Halphen, whose 10,000 books were seized and Gustave Cohen, also a specialist in medieval history, who, like others, lost the manuscript of a book he was writing, and the philosopher Jean Wahl, exiled in the United States from 1941-1945. Plundered too were professors Henri Lévy-Bruhl (3,000 volumes of Roman law), Marc Bloch and Victor Basch, both assassinated by the Militia, and so many others. A number of writers, often on the Otto prohibition lists1 were despoiled: Tristan Bernard, Emmanuel Berl, André Maurois, exiled in New York, Benjamin Crémieux was dispossessed of a precious library of 8,000-10,000 books, was deported and died in Buchenwald, Jacques de Lacretelle, Pierre Klossowski, Julien Benda, etc. The publishers Gaston Calmann-Lévy, Jacques Schiffrin, founder of the Pléiade collection and others were dispossessed of their private libraries and stock.

A number of gallery owners, antiques dealers, art dealers and collectors, most of them Jewish, were dispossessed of both their art collections and libraries. Hans Fürstenberg (Jean Fürstenberg), art dealer and collector, doubly hated as both Jew and German anti-Nazi émigré, important donor to the Bibliothèque nationale, was looted of both his artworks and library of 7,500 volumes (18th century French illustrated leather-bound books on the fine arts and their history, ancient German editions, more than 300 incunabula, numerous original editions).2 Georges Wildenstein, stripped of French nationality by Vichy, was despoiled in 1940 of his artworks and library of modern authors, containing first editions, original engravings, and a few old manuscripts.3 The art dealer and gallery owner Paul Rosenberg was dispossessed of artworks not sent abroad and of his personal library of 3,000 volumes, of which 800 artbooks marked with his initials and often dedicated, 800 professional volumes among which sales catalogs of 1938 and 1939.4 The banker David David-Weill, collector and important donor to French museums, president of the Conseil des musées de France, was despoiled of over 2,500 artworks; his rich art library, stored with a transporter, was abducted by the Germans in eight trips in June 1943.5 The gallery owner Georges Bernheim was despoiled of his artworks and his library containing several hundred annotated sales catalogs, found in Austria in 1949, and several hundred books of literature and art.6 None of the books in his art library could be restituted to Marcel Bernheim, also a gallery owner.

Justin Tannhauser, a gallery owner in Munich, Lausanne, Berlin and London, fled Germany in 1937 and exiled to New York in 1940. He was despoiled of part of his artworks and a library of 1,000 volumes on the fine arts that included luxury editions; less than 200 volumes could be restituted after the war.7 In 1929, Hugo Perls opened the Kate Perls gallery in Berlin, where he exhibited Munch, Picasso, Monet, Van Gogh and Cézanne. Exiled in France in 1931, he renounced his German nationality and exiled to the United States in 1941. His possessions, his works of art and 8,000-volume library including his catalog, were seized at the storage house he had entrusted them to by an ERR crew directed by Alfred Rosenberg’s associate, Bruno Lohse: Greek and Latin classics, literature, art history, volumes of lithographs by Vuillard, Picasso, Bonnard and Renoir. Perls suffered most from the loss of his library of philosophy and literature. Presenting himself not as an art dealer but as a writer, a specialist in Plato, he insists: “The worst for me would be the loss of the books I have collected since the age of eleven. Since I am a writer you understand, I miss them.”8 A large number of other collectors and dealers were despoiled.

Source : Bibliothèque de l'Institut national d'histoire de l'art (INHA), BCMN collections, 8 MON 56631. Document looted during the Second World War, acquired by the Bibliothèque des musées nationaux from the Domaines in 1951.

Source : Bibliothèque de l'Institut national d'histoire de l'art (INHA), BCMN collections, 8 M 0176. Document looted during the Second World War, donated to the Bibliothèque des musées nationaux by the Direction des musées nationaux in 1946.

Source : Bibliothèque de l'Institut national d'histoire de l'art (INHA), BCMN collections, 4 D 0229 (14). Document looted during the Second World War, entered the BCMN collections as a gift from the Direction des Musées Nationaux in 1946.

Source : Bibliothèque de l'Institut national d'histoire de l'art (INHA), BCMN collections, 8 H 0841. Document looted during the Second World War and donated to the Bibliothèque des Musées Nationaux by the Direction des Musées Nationaux in 1946.

The work of finding and restituting books: the sub-committee for books, at the Commission de récuperation artistique

Jenny Delsaux, librarian at the Sorbonne, accepted to organize the work of the sub-committee from June 1945 to the end of 1950, and worked tirelessly supervising tasks such as finding the storage places of looted collections dispersed in France or in the Reich Empire, having them returned, classifying and identifying them, and finally, restituting the most possible to the greatest number of looted persons. All of which had to be done with minimal budget and personnel, and despite the looming threat that the service could be shut down. Faced with the flood of books and the legitimate impatience of owners, the sub-committee was authorized to proceed to “attributions” of books without owners’ names and that corresponded the best possible to the needs of those despoiled. For Alsace-Moselle, there were two other sub-committees for the restitution of books, in Strasbourg and in Metz, where 850,000 books were found,1 but for which the restitution or attribution inventories are missing.

The sub-committee was involved in the sorting, restitution or attribution of 1,033,100 volumes when it was obliged to interrupt its activities at the end of 1949. In Paris, 260,000 books were found. After long and difficult searches in allied occupation zones, wagonloads of books in crates returned from Germany, some 773,100 volumes. In parallel, some large collections still whole, stored, for example in the Hohe Schule, were restituted directly to their owners. But the allied bombings that intensified in 1943 made it necessary to evacuate the large looted collections east of Germany, sometimes in Austria, where they would later be seized by the Red army. Millions of books and archives belonging to conquered countries went to Moscow and would then be distributed throughout the Soviet Empire. The few returns from Moscow of archives and books during the 1990s were rapidly interrupted and those seizures are still today considered legitimate “spoils of war” after the sufferings endured.

Our database, accessible on the Mémorial de la Shoah site,2 lists the names of 2,250 persons and 410 institutions to whom some 555,000 books or printed periodicals, manuscripts, iconographic documents and archives have been restituted or attributed. Only part of the books looted have been found. Also, only a minority of those despoiled and having an essential need for their books, have made a claim for restitution: the majority of Jewish families, if they survived, had small family libraries and had more vital priorities at the Liberation. How many books were destroyed when they were seized or sorted at various times in France or Germany? How many were stolen, how many disappeared or are still in East European countries? No one has a precise answer.

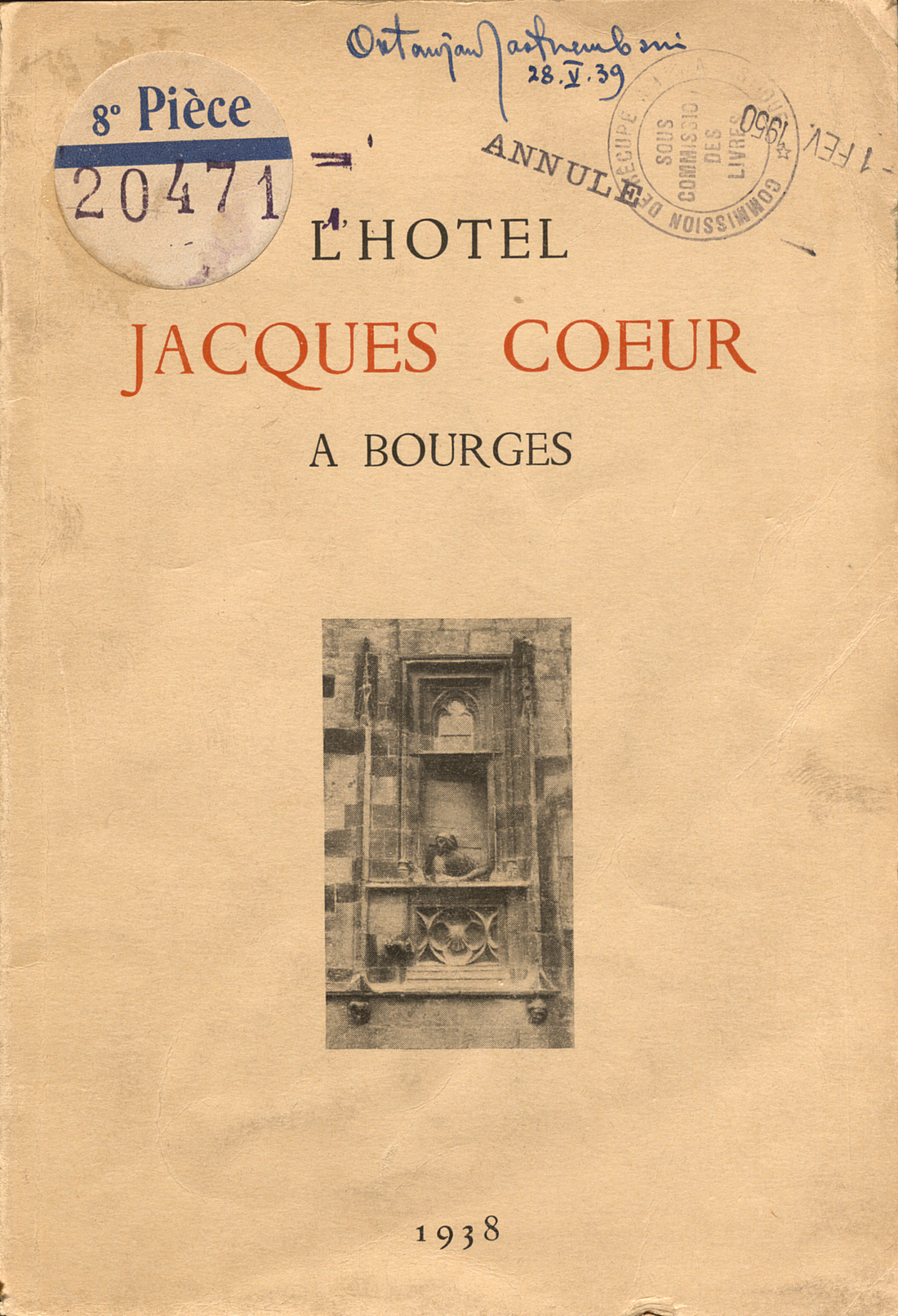

Source : Bibliothèque de l'Institut national d'histoire de l'art (INHA), 8 Piece 20471. Document looted during the Second World War, attributed to the Bibliothèque d'art et d'archéologie by the Choice Committee in 1950.

The end of restitutions and what to do with books not restituted. The Choice Committee

With some 700,000 documents remaining to be redistributed, the post-war will to forget required a legal solution. Public libraries were authorized to buy from the Domains at very low prices “ordinary” books and reviews (close to 300,000 books and periodicals), lists of which we were able to find. At the end of September 1949, a Choice Committee (Commission de choix) was established at the National Education ministry in charge of distributing among public libraries some 15,450 rare, precious or very specialized books and documents.1

The Committee met four times between 1949 and 1953. Its criteria, as we understand, a posteriori, were of two kinds: to aid libraries whose collections had been destroyed during the war; and to protect rare or precious documents by entrusting them to national libraries. In this case, it would be a matter of deposition and not attribution, wrote Julien Cain, returning, after deportation to Buchenwald, to his post as administrator of the Bibliothèque nationale and named director of the new Direction des bibliothèques et de la lecture publique at the Education Ministry. These documents went to 42 libraries: 22 research libraries and 20 public libraries. Many more were deposited in national libraries: the Bibliothèque nationale received close to 4,000 documents.

A memory lost and recovered

The libraries with a tendency to respect (too) scrupulously the terms of the deposit of documents, conserved them in crates, then classified them, unaware of their origin, and often in the 1960s, integrated them in their collections. The memory of these deposits of looted books was completely lost in the professional conscience: they became the “MNR (Musées nationaux Récupération) of the libraries.” On the discovery of these attributions, of which the French National Archives had fortunately kept lists,1 in 2015 we asked these libraries to find those documents. That task, almost completed today, sometimes gave rise to new discoveries of looted books having arrived on their shelves, no one knows how. Only rarely can they entail restitutions, since most books do not bear the name of an owner. Nonetheless, they have been at the origin of discoveries for the history of libraries, of the Occupation and the Shoah, and confirm the unfortunately eminent and multiple importance of written works in the processes of Nazi domination.

The history of the plundering of libraries during the Second World War still contains its share of grey zones. Millions of books never returned from their forced exile. In the words of Patricia Kennedy Grimsted, great specialist of these European wanderings, a very large number remain “far away from home.”2 Although specialists sent after the war to Germany, Austria and Poland estimated that German public libraries had not been attributed looted books, they now find many in their collections and make an effort to return them to their legitimate owners.

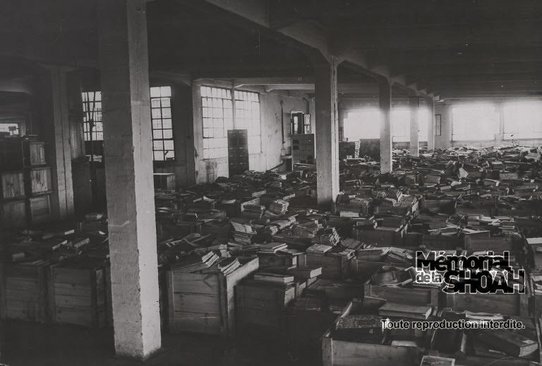

Source : Published with the consent of Archives du Mémorial de la Shoah, CIII_28_3.

Basic data

Personne / personne

Personne / personne