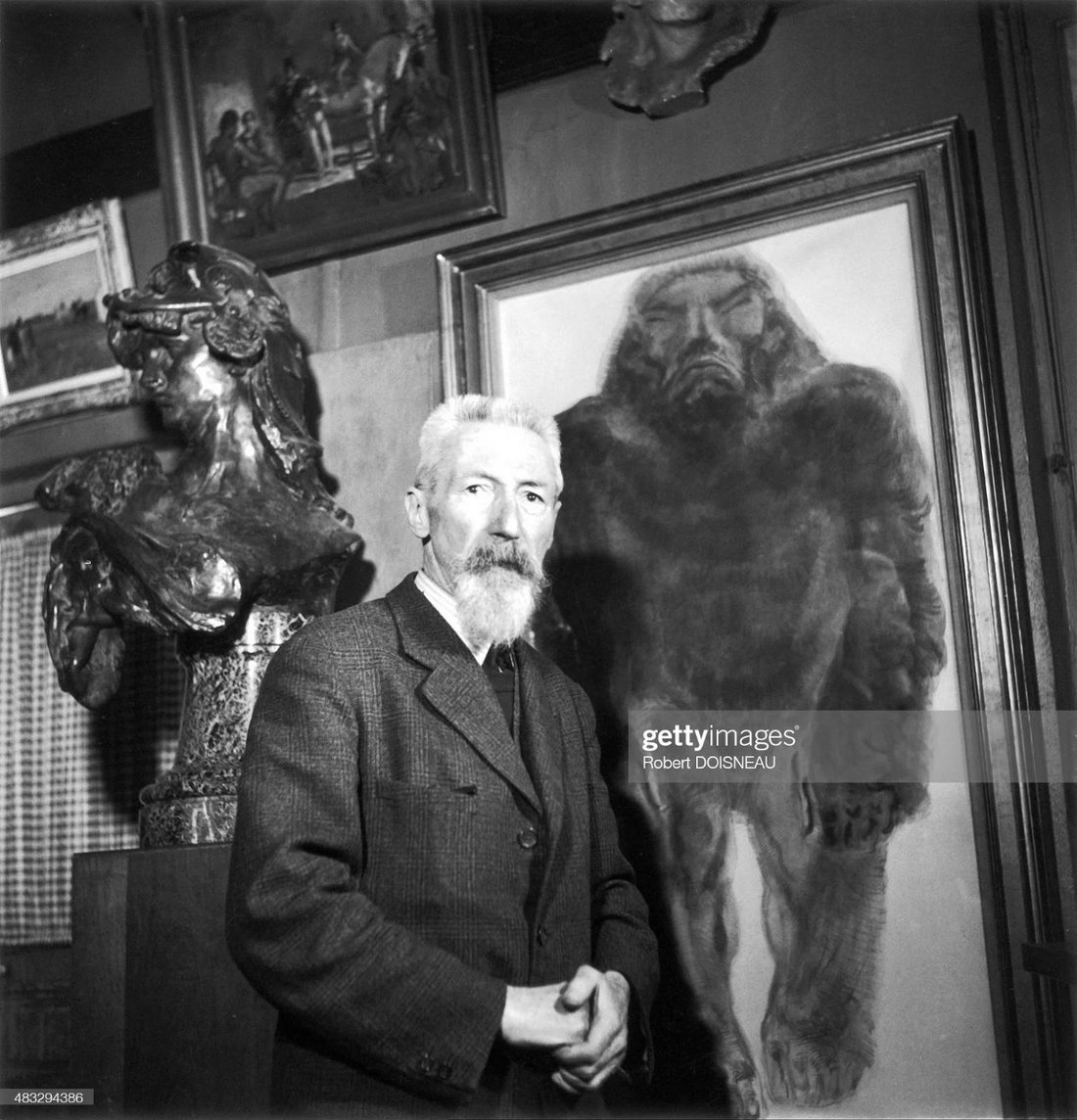

RUDIER Eugène (EN)

As of 1902, Eugène Rudier became the official caster of Rodin’s works. During the Occupation, he accepted several orders from German high officials and museums, and at the same time sold artworks, particularly bronzes from the musée Rodin. He was close to Arno Breker, but also to Franz Graf von Wolff Metternich and Hildebrand Gurlitt.

Source: Getty Images.

Caster of Rodin’s works

François Eugène Rudier was born in Paris 11 January 1879 in the 3rd arrondissement.1 His father was Alexis Rudier, caster of bronze curios since 1874, with an atelier on rue Charlot in the Marais, and as of 1880 at 45, rue de Saintonge. Eugène was the nephew of François and Victor Rudier, casters of statues and statuettes.2 Alexis died in 1897 and Eugène took over the casting enterprise with his mother, specializing in sand casting. He became the official caster of Rodin’s works as of 1902 and continued to work for the jewelers Chaumet and Boucheron. At first, Rudier signed his bronzes with the stamp “Rudier (Vve Alexis) et fils,” then “Alexis Rudier.” He established his personal address at 84 avenue Georges-Clemenceau in Vésinet, as of 1918. He died on 18 June 1952 in Malakoff. His archives were burned and his molds broken, as he had ordered in his last wishes. He is buried in the Vesinet cemetery (Yvelines), a large proof of Rodin’s La Grande Ombre on his tomb.3

In 1919, the foundry atelier was at sis 45, rue de Saintonge, abandoned in 1935. In 1919, Rudier also transferred part of his atelier to 37, rue Olivier de Serres, in buildings previously occupied by the Griffoul foundry. As of 1934, the enterprise moved to 12-16, rue Leplanquais in Malakoff, where it employed between forty and sixty workers. Close to three hundred names of artists of artists appear as clients, sculptors or ornamentalists on Rudier’s casting registers.4 The name Arno Breker appears as of March 1929, but we also find the names of the sculptors Antoine Bourdelle, Aristide Maillol (as of 1905), Charles Despiau and Paul Belmondo, who had the proofs of their sculptures made in the atelier of Eugène Rudier.5

During the 1937 World Exhibition, Eugène Rudier was at the peak of his renown: he obtained orders from the state (Despiau’s Apollon, an order never delivered on time by the artist), and became the exclusive caster for the musée Rodin, in charge of the sculptor’s copyright. In a building near his atelier in Malakoff, Rudier assembled his personal collection: sculptures, paintings and drawings that artists gave him and that he could resell. He had friendly relations with artists and took in Antoine Bourdelle at the end of his life, from the month of May until his death on the 1st of October 1929.6 He was also very active on the art market.7

Castings and sales of bronzes for German museums and high officials

Too old to be mobilized when World War II broke out, Rudier continued to cast bronze proofs. His excellent reputation and powerful friends enabled him to escape the prohibition to use bronze for anything but military production.1 He took advantage of a period that was extremely difficult for his competitors and a hegemony for himself. The records of casting orders for the Rudier enterprise are uninterrupted from 1939 to 1945 for Rodin's artworks and give a precise idea of the foundry’s activity.2 In fact, Franz Graf von Wolff Metternich arrived in Paris in August 1940 and remained there until 1942, and during that entire period, Rudiez was required for the casting of bronzes for German museums or officials.3 The agenda of Heinrich Ehmsen4 for the years 1941 and 1942, conserved in the Diplomatic Archives show the founder’s position.5 The accounts mention the name of Rudier almost daily, but also the names of those he met with at Ehmsen’s: Rudolf Wolters, Hanns Dustmann, Charles Despiau, Werner Lange, etc., and of course, Arno Breker, since it was a matter of the months preceding the exhibit of the German sculptor at the musée de Orangerie. Concerning that event, the painter noted, on 7 April 1942; “Material for Rudier by the military administration.” He was welcomed at the musée Rodin on 22 May 1942 at the reception in honor of Arno Breker.

Official caster of the musée Rodin, Rudier exhibited two works from his collection during the Monet-Rodin Centenary exhibition at the musée de l’Orangerie, 7 December 1940 to 16 March 1941.6 During the Second World War, fewer sculptors called on Rudier: Aristide Maillol, Charles Despiau, Paul Belmondo, Alfred Janniot. At Arno Breker’s request, Rudier received the order to cast the Porte de l’Enfer for Hitler’s Linz museum. He cast all the bronzes for Berker’s exhibition at the Orangerie in 1942, then a number of castings until November 1944. Among them, those destined for the beautifying of Berlin in the context of the “Germania” project led by Albert Speyer for Hitler; they were cast until November 1944.7

Rudier acted as an intermediary or art dealer for the works of Maillol and especially for Rodin castings: between October 1941 and December 1943 he acquired over fifty bronzes from the musée Rodin for German museums or private persons.8 Some of these bronzes are among the works found by the artistic recuperation, like L’Âge d’airain, Adam, Ève, La Grande Ombre, Le Baiser, monumental, L’Enfant prodigue, Saint Jean-Baptiste,9 but also L’Homme qui marche, moyen modèle and Le Penseur, moyen modèle for Arno Breker,10 Orphée, Les Bénédictions, l’Exhortation, and other less important works. Finally, he acquired the monument of the Bourgeois de Calais for the Wallraf-Richartz museum in Cologne, or obtained the order for the casting of a proof of the above-mentioned Porte de l’Enfer. Rudier made fewer purchases from the musée Rodin beginning in 1943 (three for a certain M. Ilg in Brussels) and in 1944 (seven acquisitions for a M. Romeis [sic]).11 He purchased these castings for a price corresponding to the original price of the cast iron. It was thus that castings of the late 1920s were estimated according the prices of those years, without taking into account the increase in prices during the following years.12

The main recipients of those acquisitions were the Städtische Galerie (Städel museum) in Francfort-sur-le-Main, the Landesgalerie in Salzburg,13 the Düsseldorf museum, the Wallraf-Richartz museum of Cologne and the Linz museum.14 The other works were sold to private persons, often unknown to this day. Hildebrand Gurlitt and Friedrich Welz bought works from him that were sometimes recovered at the end of the war.15 Diplomatic and/or American archives possess documents attesting to Rudier’s activity during the Second World War: bills for sales of bronzes to museums, to private persons.16 In that way, we learn that Rudier was aided by the German authorities to obtain the material needed for the purchases of the Städtische Galerie of Francfort-sur-le-Main, which Ehmsen’s agenda already told us.17

Post-war pursuits

Rudier’s activities were signaled as of August 1944, as shown by the August 1944 letter of the foundry’s personnel and the dossier “Affaire Rudier, classée sans suite, mars 1945-février 1946” (Rudier affair, closed as a non-case, March 1945– February 1946)” conserved in the Archives diplomatiques.1 Rudier was called up by the Comité de confiscation des profits illicites on 9 December 1944,2 and as of January 1945, the second Comité de confiscation des profits illicites examined both his activity as a caster and that of art dealer.

The rapporteur Flaujac pointed to Rudier’s motivations in dealing with the Occupant.3 He then looked more closely into the company’s careless accounting: irregularity of accounts, cash sales, incomplete declarations of profit to the tax authorities, black market purchases of metals,4 metal stocks badly evaluated, complicity between the professional activity of a caster (known as “industrial income”) and the private activity of a collector (“business income”), gifts of artworks as a way of paying artists for their casting orders, those works being later integrated into Rudier’s personal collection without being entered into the foundry’s stock as financial input, Rudier’s lies.5 Finally, the rapporteur concluded:

“outside his activity as a caster of artworks, M. Rudier is a collector and dealer in artworks. He admits that this side activity is much more lucrative than his official activity (…) should profits of that kind, in theory, escape schedular taxes and confiscation (being non declared)? We do not think so. M. Rudier’s two orders of activity are too closely linked, whatever he may claim, to be dissociated (…) the results shown by the accounting, for previously mentioned reasons, are to be simply discarded (…) The estimation of these profits can only be made in terms of an overall appreciation (…) Only detailed and complete inventories of works possessed on 1/9/1939 and on 31/12/1944 with the indication of all the purchases and all the intermediary sales, including the names and addresses of dealers and buyers, could allow a precise estimation. These inventories do not exist, or if they do, have not been found. The insurance policies contain no detail of the goods insured.”6

The result was a confiscation proposal of 4,300,000 F and a fine of 2,150,000 F. On 13 February 1945 the Comité decided on a confiscation amount of 4 300,000 F and a fine of 3,000,000 F.7 Provisional measures were decided in March 1945.8

Rudier initiated an appeal as of the first of March, which was rejected by the Comité on 13 February 1946.9 He then appealed, on 30 March 1946, to the Conseil supérieur de confiscation des profits illicites, formulated two requests for extensions in May and in July 1946, which were accepted in June and September of the same year.10 Meanwhile, the rapporteur, Faujac, wrote a supplementary report in answer to Rudier’s appeal.11 That report, of 11 July 1946, proposes separating the industrial income (foundry) from the business income (sales of artworks), and lowering the confiscation amount to 1,800,000 and the fine to 1,000,000. This proposal was taken up by the Comité de confiscation des profits illicites during its 18 December 1946 session.12 The decision was enacted on 15 January 1947, and Rudier withdrew his appeal “purely,” as specified in the 29 April 1947 decision of the Comité.13

The affair was considered closed, as attested by a response of the Comité de confiscation des profits illicites to the Office des biens et intérêts privés (OBIP, Office for Personal Property and Interests) on 6 February 1950, concerning a monumental fountain cast by Rudier and found in Germany.14 However, Rudier’s days of glory were over: Jacques Jaujard and Marcel Aubert demanded the recuperation of all plaster casts remaining in his atelier, increased surveillance of metal stocks, the follow-up of orders, and finally, a detailed accounting on the part of the musée Rodin during the postwar period.15

In conclusion, Rudier managed to overcome obstacles thanks to his relations with powerful figures: Breker, but also Metternich and Gurlitt, who remained untouchable after the war. He proved to be an extremely efficient and cynical art dealer, not hesitating to acquire casts from the musée Rodin at totally outdated prices, to get round the royalties of certain sculptors, Maillol in particular, to believe himself “above the law” where taxes were concerned, lying shamelessly, with contempt for the activities of the Comité de confiscation des profits illicites investigators, unable at the time to state the volume of sales of artworks in Nazi Germany, since the inventories of the Salzburg Landesgalerie and the Linz museum were not yet known. Furthermore, the lists of purchases of artworks during the Occupation by German museums could not yet be consulted, as is rightly noted by the rapporteur, Flaujac, in his 20 January 1945 report. Rudier thus succeeded, in quasi-impunity, in amassing a personal collection thanks to payment in kind to his enterprise, and in acquiring works at low prices and selling them without being penalized.

Basic data

Personne / personne