AYMONIER Étienne (EN)

A Field Orientalist

Étienne Aymonier, a naval infantry officer and colonial administrator stationed in Indochina, was one of the great figures of "field" Orientalism, remembered by posterity for his systematic explorations of the Indochinese peninsula. While workingas an archaeologist, he surveyed the remains of ancient Khmer and Cham cultures. As a pioneer in epigraphic studies, he supplied Indian scholars with Khmer and Cham inscriptions, from which he brought the ancient kingdom out of the mists of the past.

He surrounded himself with many local assistants, whom he often sent upstream or on parallel routes during his exploration missions, in order to locate and cover terrain as well as possible. He trained them in the stamping (estampage) of inscriptions, as well as in taking notes, plotting itineraries with a compass, and using a stopwatch. This method made it possible to trace the routes after the fact. Aymonier readily acknowledged his debt to his local informants.

Coming from a Savoyard family of farmers, he passed the entrance examination to the École militaire de Saint-Cyr in 1866. He was assigned to the occupation corps of Cochinchina and landed in Saigon in October 1869. Upon his arrival, he became interested in local life and people. After being noticed by his superiors, he was assigned to the inspection of indigenous affairs in southern Vietnam, where a Cambodian community had longbeen settled, and he began to learn the language (BEFEO, 1929, obituary by Cœdès). In 1873, he was appointed deputy to the representative of the Protectorate of Cambodia, Jean Moura. But the College of Trainee Administrators in Saigon recruited him to teach Khmer in 1874, before appointing him director (1877-1878). For the purpose of teaching, Aymonier set about writing instructional books: vocabulary, a dictionary, and Cambodian lessons, soon followed by his main publications concerning this language, a Dictionnaire khmèr-français et des Textes khmèrs (1878).

From 1879 to 1881, he succeeded Jean Moura as representative of the Protectorate of Cambodia; he took the opportunity to embark on various tours of the country, during which he could copy and translate modern Khmer inscriptions. Published in the journal Excursions et reconnaissances, in Saigon, these inscriptions were of immediate interest toIndianists, especially by enablinganinitial, more or less reliable dating. InLe Cambodge. Le groupe d’Angkor et l’histoire (1904), Aymonier cautiously advances: "The historian, bound to verify and coordinate events, also has the higher mission of discovering and in some way resuscitating these vanished societies and their vanished institutions. But the task of making a sufficiently clear and exact historical sketch, by substituting positive facts or at least plausible hypotheses for the mirages of confused fables, is not without presenting great difficulties here. Even in the current state of science, after all the discoveries we have made or contributed to since 1880, truly historical documents only have relative value” (Aymonier É., 1904, p. 326).

In order to carry out a quality epigraphic study, the Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres decided to commission him officially to gather a large harvest of inscriptions: "The Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres heard with great interest the communication by M. Aymonier, administrator in Cochinchina, on the epigraphic documents he discovered in southern Indo-China. The academy was very struck by the importance of the results obtained and hopes that Mr. Aymonier will be able to continue his research as actively as possible. The academy unanimously expressed the wish that the Minister of Public Instruction entrust Mr. Aymonier with an epigraphic and philological mission in Cambodia and in the former Ciampa. It requests the Minister of Public Instruction to recommend to his colleague, the Minister for the Colonies, this mission which would be placed under the direction of the Governor of Cochinchina" (Comptes rendus des séances de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles Lettres, 1881, 25-4, pp. 236-237).

Aymonier was now free to devote himself fully to archaeological and epigraphic exploration, which he needed to carry out in a more scientific manner and with a better copying process than the tracings he had heretofore created throughestampage (stamping). Moulded stampings (dubbed“à la Lottin de Laval”) were followed by others in India ink, by smearing the paper applied to the stone. From 1882 to 1884, three campaigns lasting several months led him to criss-cross the whole country, Laos, part of Siam. Then he turned to southern Annam in search of the lost grandeur of the kingdom of Champa, much to the chagrin of local officials, when he decided to settle in the village of Mai-van. "It was assumed or hoped that I would land here and direct myself towards Khânh hôa, the neighbouring province, and from there towards the north. The disappointment must have been great when I announced my intention of settling for a few months among the Chams of Phanrang in order to study their language and collect their manuscripts," he explained in a letter to the governor of Cochinchina” (published in 1885 in Saigon, p. 2).

Indeed, Aymonier had developed a true passion for Champa: “I was very curious to see, for the first time, the writing of Cham epigraphic documents [...] For the size, the perfection of the layout, the good state of preservation, the inscription that I have just seen at the Phanrang tower rivals the best in Cambodia. And the natives indicate to me, a day farther west, much finer and much larger inscriptions, they say. The epigraphic riches of this country are truly considerable.

“In all likelihood, the language of the inscription on the Phanrang Tower is Sanskrit. Even if it is vulgar, I cannot approach the study of these documents before becoming master, as much as possible, of the current knowledge of the Chams.

“Their manuscripts are numerous. They claim to use nine kinds of writing, which would make ten with that of the Chams of Cambodia that I already know. It is probable, however, that these numerous varieties of writing will be reduced to three or four in the end if one disregards the embellishments that do not affect the body of the typeface. These Chams do not decipher the inscriptions of their ancestors.

"So there is a lot to do here. I have brought with me five Chams from Cambodia, who are at present indispensable to me in order to relate to their shy and fearful brethren" (ibid. p. 6).

The Comptes rendu des séances de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles Lettres setail the progress of the work. “M. Bergaigne communicates a letter he received from M. Aymonier. This letter is dated Quin-hon, July 21. Despite the difficulties created for him by the troubled situation in Annam, M. Aymonier visited several provinces and noted a certain number of new inscriptions, some Sanskrit, others Cham. One of the Sanskrit inscriptions is Buddhist. M. Aymonier also continues his studies on the Cham race, whose domination preceded that of the Annamese on part of the eastern coast of Indo-China” (1885, 29-3 p. 231).

Unfortunately, the mission was cut short when a movement resistant to colonisation broke out after the capture of Huê by French troops. Aymonier had to give up pursuing it, but his notes, added to those of his assistants, helped him to publish various works on Champa, including a grammar and a Dictionnaire cham-français, along with Antoine Cabaton (1863-1942), one of the first members of the Archaeological Mission of Indochina. Returning to France in 1888 as delegate of Annam-Tonkin at the Exposition universelle of 1889, he was appointed director of the newly created École coloniale where he also taught Khmer until his retirement in 1905. Made a Chevalier de la Légion d’honneur in 1883, he was appointed member of the Conseil supérieur des colonies in 1910.

However, neither the "field" scientist nor the administrator enjoyed unanimous support whether in academic circles or the hierarchy. While he contributed to bringing the future École française d’Extrême-Orient to the baptismal font, a bitter controversy over Founan pitted him against Paul Pelliot (1878-1945) who reproached him for his dangerous individualism in scientific matters. His self-taught side bothered scholars: his candidacy as a free member of the Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres, which had once praised him, was refused twice. He developed some resentment. In addition, his character, sometimes described as "rough", his independence of mind, and the proposals for reform of the colonial administration, expressed in a rather abrupt way, ended up doing him a disservice.

Étienne Aymonier today remains an essential reference in Khmer and Cham studies, however largely shunned, or, to use the ambiguous formulation of George Cœdès (1886-1969) in his obituary published in the Bulletin de l'École française d'Extrême-Orient in 1929: "When the progress of studies will have relegated his work to the number of works which have no more than a bibliographical interest, the work accomplished during his mission of 1882-1885 which founded Khmer epigraphy on a solid and resuscitated the Chams ignored before him, this work will remain as a testimony of his labor and his devotion to science, and will suffice to assure his name an eminent place in the history of Indochinese studies" (BEFEO, 1929, p. 542-548).

The collection

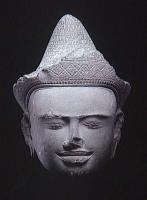

In addition to hundreds of stampings, Aymonier collected stelae and statues during his missions. Their identification, however, later proved to be complex: “The statues brought back by Monsieur Aymonier were first deposited in the Musée d’Ethnographie, where they do not seem to have ever been cataloged or labeled seriously. When they moved from there to the Musée Guimet, they unfortunately neglected to draw up even a simple list of them, and nothing provides the authorisation to affirm that the collection of the Musée Guimet corresponds entirely to the old collection of the Musée d’Ethnographie. In fact, I have not been able to find a certain number of pieces that M. Aymonier, in his works, mentions as "definitely" at the Musée Guimet; on the other hand, I do not know the exact provenance of three-quarters of this collection, no one having taken care to take note of it in good time", complained Georges Cœdès in 1910, in his Catalogue des pièces originales de sculpture khmèrekept in the Musée Indochinois du Trocadéro and at the Musée Guimet. About twenty years later, in the Catalogue des collections indochinoises established by Pierre Dupont (1934), Jeannine Auboyer (1912-1990) recalls the grouping of Khmer sculptures in the entrance rotunda on the initiative of the curator, Joseph Hackin, in 1921. "This first grouping consisted mainly of the Aymonier collection: the two most remarkable pieces were the Harihara of Maha-Rošei and a very beautiful Buddhist head […]. Let us not forget that, from his missions, Aymonier had also brought back a large number of stampings taken from inscribed stelae, and even a few of these stelae. The stampings were deposited in the Bibliothèque nationale and the Société asiatique; the stelae, twelve in number, are kept at the Musée Guimet. They bear inscriptions dating, for some, from the 7th century AD and giving the names of the first known Khmer kings […], others from the 11th century and more particularly from the reign of Sūryavarman I" (Dupont P., 1934, p. 19 and 21).

Related articles

Collection / collection d'une personne

Personne / personne