MALINET Nicolas Joseph (EN)

Biographical article

Nicolas Joseph Malinet was one of the most prominent figures in the sale of Far-Eastern objects in Paris. Although his career in the world of curiosities began late, he was one of the first to specialise in trading in Asian art, and throughout his long career he played an essential role in the expertise and diffusion of these objects.

From a tailor to a dealer in paintings

Nicolas Joseph Malinet was born in Paris, on 31 March 1805.The son of Nicolas François Malinet, an artisan, and Marie Reine Crèvecœur, he started out working as a tailor. According to the auctioneer Charles Pillet, who wrote one of the rare accounts about him, Malinet already had a passion for art, and readily accepted a painting as remuneration for his work as a tailor (Pillet, C., 1887, p. II). He gradually came to know experts, dealers, and collectors, and as a result of the conversations he had in these enlightened circles, he gradually enriched his knowledge of the world of the arts and curiosity. One of these initial contacts with the art world was the expert Alexis Joseph Febvre (1810–1881), the dealer in pictures and expert François, the expert in ancient pictures François Adolphe Warneck (the father of the famous collector Édouard Warneck (1834–1924), and the dealer Jean-Jacques Meffre, who introduced him to the Comte de Morny, for whom he acted as an intermediary (Emlein, R., 2008, pp. 80–81). As attested by this network, Malinet’s initial passion was for paintings.

The repertoire of Fritz Lugt’s sales mentioned several sales between 1841 and 1842, during which Nicolas Joseph Malinet started his career as an expert in pictures in the company of the auctioneers Bierfuhrer, Benou, and Devilliers (16068, 16391, 16421, and 16613); and all the sales mainly comprised pictures.

He gradually abandoned his metier as a tailor, opting instead to focus on selling pictures; and, after several years, he managed to open a curiosity shop at 25, Quai Voltaire at the age of thirty-seven. Malinet’s shop was listed under the Bottin heading ‘curiosities’ from 1854 to 1890 (Prost, L., and Valluy, C., 1975, p. 233). This choice of address was quite deliberate as he moved right into the antique dealers’ district, on ‘the quay that one might describe as the quay of curiosities and ornaments’ (Pillet, C., 1887, p. I). As his expertise increased, he won the trust of the major collectors, for whom he acted as an intermediary. He was largely responsible for enriching the collection of pictures of Lieutenant-General Hyacinthe François Joseph, Comte Despinoy (1764–1848), which was sold after the death of the latter in 1850 (Lugt 19609). 25, Quai Voltaire was soon frequented by some of the most important collectors of art and curiosities; Charles Pillet mentioned the judge Jacquinot-Godard (see the many post-death sales between 1858 and 1859: Lugt nos. 24537, 24598, 24622, 24666, 24727, and 24776), the statesman and future President of the Third Republic Adophe Thiers (1797–1877), the Duc Hubert de Cambacérès (1798–1881), a peer of France and Grand Master of Ceremonies under Napoleon III, the Baron Thibon (died in 1875?, post-death sale: Lugt 35344), Eugène Tondu (died in 1865, post-death sale: Lugt 28424, 28445, 28476, 28513) and the abbot Dufouleur (died in 1856, post-death sale: Lugt 22786 and 25853). The decorative arts had pride of place in these extensive collections: that of Adolphe Thiers, bequeathed to the Louvre, is one of the most famous examples of this (Blanc, C., 1884). To satisfy the demands of his clients, the latter increasingly focused on acquiring every kind of objet d’art. Hence, he is believed to have supplied most of the enamel objects in the collection of the Baron de Theïs (died in 1874?), which at the time of the baron’s death comprised no less than 181 Limoges, Byzantine, and Venetian enamels (Lugt 34861); Italian faience objects of the Marquis d’Azeglio (some 122 lots sold in 1868, Lugt 30333); ivory objects from the Dufouleur Collection (more than 300 carved ivory objects dating from the fifteenth to eighteenth century were sold upon the abbot’s death in 1856, Lugt 22786); miniatures by Jacquinot-Godard (around one hundred lots, Lugt 24622), as well as the whistles that belonged to Louis Clapisson, a professor at the Conservatoire de Musique and member of the Institut Louis Clapisson (1808–1866; the catalogue of his post-death sale listed more than 150 objects, Lugt 29126). This enumeration gives an idea of the diversity of the objects sought by Malinet, as it beautifully illustrates his ability to satisfy the requests of his clients with their refined taste.

The Far-Eastern arts

In 1857, the post-death sales of the collections of Louise Antoinette Scholastique Guéheneux, Maréchale de Lannes, and Duchesse de Montebello (1782–1856; Lugt 23338, 23368, 23407, 23417, 23441, 23493, and 23507) marked a turning point in Nicolas Joseph Malinet’s career. This was one of the most important sales of the nineteenth century for the Far-Eastern arts: held over several days between February and April 1857, these sales comprised a total of almost 120 lots of Japanese porcelains, 372 Chinese porcelains (some of these lots exceeded one hundred objects), including eighty-six with gilt bronze mounts, several dozen items of furniture in Japanese lacquer, 219 lots of lacquered objects from China and Japan, forty-four Chinese and Japanese bronzes, jades, silk textiles, and so on. Entrusted with many acquisitions on behalf of his clients, he also acquired objects for himself. Edmond de Goncourt descried in his Journal ‘a small lacquered cabinet from the Montebello Sale, bought by Mallinet [sic]’ on behalf of Adolphe Thiers 2,700 francs (Goncourt, E., 17 October 1884, p. 1108). The record of this sale, unfortunately absent from the Paris Archives, does not give one an idea of the extent of Malinet’s acquisitions, but for Charles Pillet it was a fait accompli and ‘henceforth, Chinese objects became the main source of his business and, at the same time, his fortune’ (Pillet, C., 1887, p. V). Malinet now had an incontestable role to play in the sale of curiosities: ‘He succeeded in invigorating the trade in Far-Eastern objects, he educated his customers, and became the official supplier of all those who sought eggshell, turquoise blue, and marbled dishes; he was the heart and soul of all the sales of these kinds of objects’ (id.). The role played by Nicolas Joseph Malinet in the sales of Asian art as of 1860 was considerable. According to Léa Saint-Raymond, in his remarkable study of sales of Asian art in the nineteenth century, Malinet ‘acquired 10% of the lots in this segment, in large quantities, for a total of 336,114 francs, or 20% of the global product on the market’ (Saint-Raymond, L., 2021, p. 247).

At one point, Malinet sold the objects from his stock—or perhaps his collection, it is difficult to be sure—in a public sale held on 28 November 1863 by the auctioneer Charles Pillet (Lugt 27560). The sale comprised porcelains, lacquered objects, jades, and other objects from China and Japan. The sale was only moderately successful: the total sale price of only 10,660 francs was the equivalent of around 83 francs per lot, and few objects sold for more than several hundred francs; and many were bought by Malinet himself at the sale, who no doubt considered that the sale prices were too low (AP (Paris archives), D48E3 54). Therefore, it is difficult to interpret the role of this sale in the dealer’s career—was it a way of selling off some of the less interesting objects in his stock? In any case, it is the only public auction of Far-Eastern art attributed to him, and the rather inconclusive experience led him to focus on his shop and direct contact with the collectors.

Certain archives highlight his role as an intermediary. Hence, in Salomon de Rothschild’s book of sales held between 1862 and 1864, there were numerous mentions of the name Malinet, to whom Salomon paid the sum of 58,108.45 francs in just two years for his many acquisitions (Abrigeon, d’ P., 2019, n. 11). Charles Pillet also pointed out that ‘the Duc de Morny [Charles Auguste Louis Joseph Demorny, called Duc de Morny 1811–1865] placed his entire trust in him, and sent a princely clientele his way’ (Pillet, C., 1887, p. V).

Incidentally, it was very probably the Duc de Morny who recommended him to the Empress Eugénie in person in order to carry out an expertise of her Musée Chinois in Fontainebleau in 1863. It was indeed Malinet who was mandated to assess the value of the various ‘collections’ in the museum, that is to say the objects donated by the Embassy of Siam in June 1861, the spoils of war—almost 500 articles—brought back after the pillage of the Summer Palace (Yuanmingyuan [圓明園]) by the Franco-British troops in China in 1860 (ACF, 1C160/1 and 2). These were complemented by works the Empress Eugénie had acquired from Malinet to enrich her Musée Chinois (Droguet, V., 2018, p. 144–145), such as silk embroidered tapestries (kesi), carved wooden panels, which blended into the decor, and an ensemble of bronze vases (Granger, 2005, p. 143). And the Musée also housed objects acquired at the post-death sales of the Duc de Morny in 1865, sales for which Malinet was also assigned as an expert (Lugt, 28746). The total value attained the imposing sum of 1,808,129.50 francs, with monumental cloisonné enamels being some of the most expensive items (Thomas, G. M., 2018, p. 154).

The Musée Chinois in Fontainebleau was not the only link Malinet had with the sales of the objects from the Summer Palace. As demonstrated by Léa Saint-Raymond, he was also the main purchaser at the Yuanmingyuan sales that were held in Paris in 1860–1870 (Saint-Raymond, L., 2021, pp. 232–233; Howald, C. and Saint Raymond, L., 2018, p. 15).

Nicolas Joseph Malinet and his clients

Amongst his most loyal clients, Charles Pillet mentioned the banker and former Consul General of Persia in Paris, Hermann Oppenheim (circa 1821–1876), and ‘Mr Dutuit’. The very rich Oppenheim Collection featured in the sale of a heritage held over several days between 23 and 28 April 1877. According to Charles Pillet, Malinet acquired for him Ernest Meissonnier’s Portrait du Sergent, the prime lot in this sale attributed to Lurville, for the colossal sum of 100,000 francs (AP, (Paris archives) D48E3 67). Edmond de Goncourt also bought several ‘bronze and lacquered objects (…) from Mallinet [sic]’ (Emery, E., 2020, p. 36, n. 88, see also p. 58). The notebooks of the collector of Chinese porcelain, Ernest Grandidier (1833–1912), are filled with mentions of acquisitions from Malinet, even though he was not his main supplier (AN (French national archives), 20144787/13; Chopard, 2020, p. 7, n. 30),

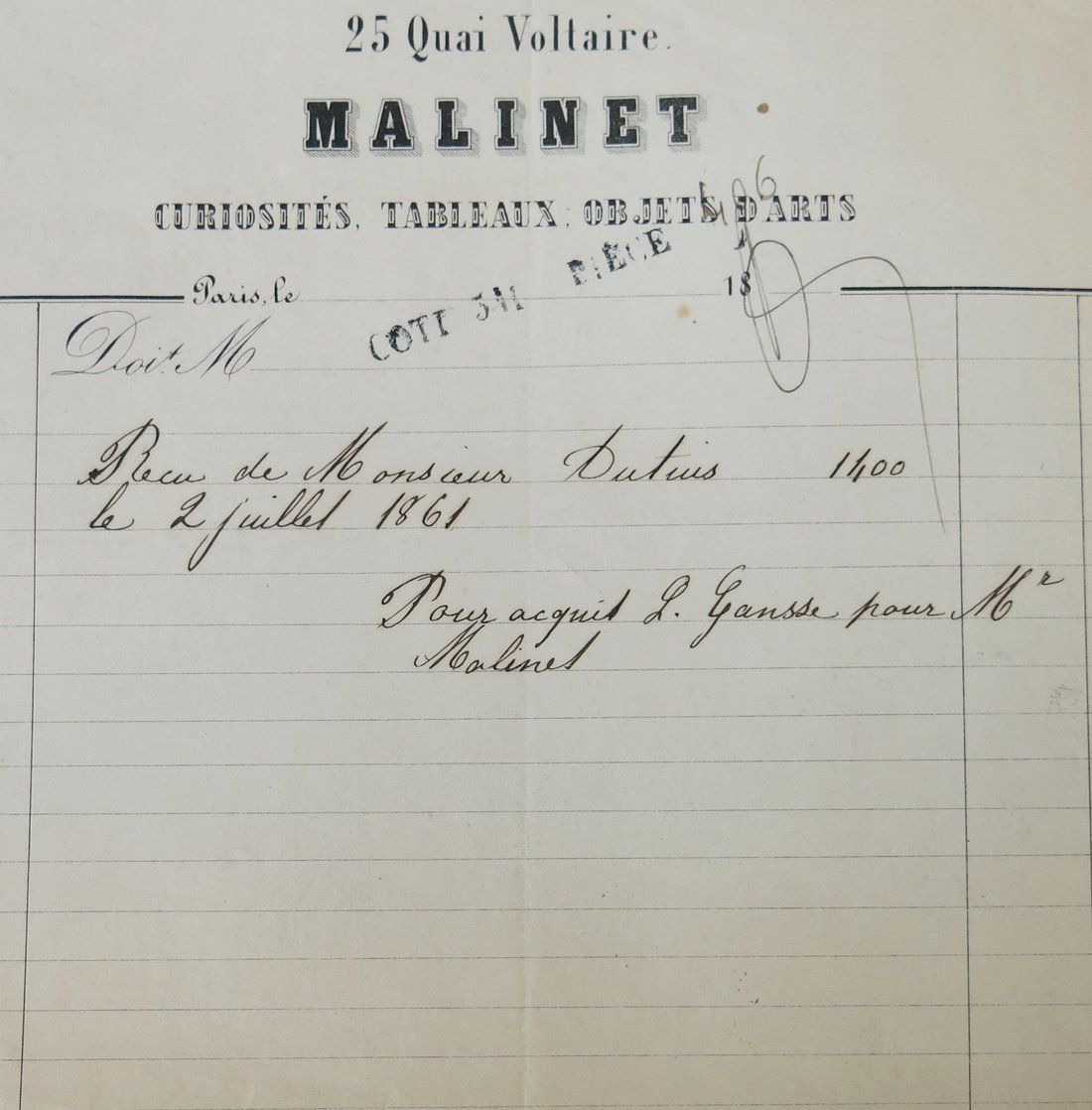

The archives of the Dutuit brothers provide the best evidence of his role as a dealer and agent. His main contact seems to have been Eugène Dutuit (1807–1886), who compiled a huge collection of art—comprising more than 18,000 objects, including a section devoted to Asian art—with his brother Auguste (1812–1902) and his sister Héloïse (1810–1874) (see the article about Dutuit, De Los Llanos, J.). Their collaboration began in 1861, as attested by a receipt for 1,400 francs dated 2 July, and the last from 1888, that is to say two years after Nicolas Joseph’s death, is a receipt for 1,000 francs signed by the nephews and heir of the latter, Henry Grimberghs (ADSM, 220 JP 2119). The correspondence of the Dutuits, held in the Seine-Maritime’s departmental archives, provides a rare insight into the relations between a dealer and his clients in the nineteenth century. Not only was Malinet commissioned to make purchases at auctions, sometimes even going to London to do so, but he also stored and looked after some of the Dutuits’ objects and packaged them for exhibitions (ADSM, 220 JP 2068). It was not unusual for the Dutuit brothers—in particular Auguste, who kept abreast of the acquisitions from Rome—to express to one another their dissatisfaction over Malinet’s purchases on their behalf at auctions: in a letter to his brother Eugène, Auguste Dutuit wrote: ‘it is a pity [therefore] that Mr Mallinet [sic] thought it better to buy a Persian object at the Larderel Sale, rather than a Hispano-Arabian one. I do believe that there were some very fine ones indeed’; later on, Auguste complained that ‘Mr Mallinet [sic] bought a robe that cost the earth and which is worth nothing, as it is a contemporary piece’ (ADSM, 220 JP 2068, transcription by José de Los Lanos). Their communications show that the commissions given to Malinet were not related to a specific type of object, but rather all kinds of works, from the high-relief works of Luca della Robbia to Louis XIV-style candelabras (ADSM, 220 JP 2068).

The list of Malinet’s numerous clients would be too long to enumerate. An obituary published in Le Gaulois on 1 April 1836 mentioned the Comte de Mniszeck, the Duc de Perigny, and Khalil-Bey LL (Bloche, A., 1886, not specified). Léa Ponchel has in fact shown that Philippe Burty had acquired miniatures from Malinet (Ponchel L., 2016, Vol. II, p.) .

Private life

On 20 July 1830, Nicolas Joseph Malinet married Marie Antoinette Schlotterer (1811–1881) (AP (Paris archives), 5Mil 2060 2945-2947). The couple had a daughter called Marie Élisa Camille, who died prematurely at the age of nine in 1851 (AN (French national archives), MC/AND/XXVI/1427). The portrait of Camille, a girl with a doll-like face, with two pigtails pinned behind her ears, is represented in a medallion on the family sepulchre in the cemetery of Montmartre (33rd division). This is the only known family portrait. During the Commune, Malinet and his wife sought refuge in Brussels, leaving the shop under the surveillance of Henry Grimberghs (Vogt, G., 2018, p. 105). The shop managed to survive undamaged (ADSM, 220 JP 2068). Shortly after his wife’s death in 1881, Nicolas Joseph Malinet adopted Louise Molas-Page (born on 26 October 1851 in Gaillard, AN (French national archives), MC/AND/XXVI/1386), who married his nephew and collaborator Henry Grimberghs (AP (Paris archives), V4E 1954). The couple lived at the same address as Malinet, at 43, Rue de la Chaussée-d’Antin. Louise was the natural daughter of Marie Molas, called Page, a single woman who lived at 40 Rue de Verneuil, and an unknown father. Her mother only acknowledged her later, on 15 February 1860. As indicated by Nicolas Joseph Malinet in his will, he and his wife saw Louise as their own daughter because they had brought her up since the age of five (AN (French national archives), MC/AND/XXVI/1427). Nicolas Joseph made her his universal legatee and bequeathed half of his inheritance to his nephew Henry. It appears that the cohabitation with his nephew was not always easy; in a letter sent to his notary dated 6 September 1882, he wrote about him as follows ‘My nephew has made life difficult for so long that I take every possible precaution to ensure those I love receive the inheritance I am leaving them’ (AN (French national archives), MC/AND/XXVI/1427).

The name Malinet was often present in Parisian auctions until the 1880s. It featured in all the major sales of Chinese porcelains from this period, such as the sales of Octave Frémin du Sartel (1882, see article about Sartel, byAbrigeon, d’ P.), Marie Nanine Labrousse, the widow of Étienne Anne Escudier (1883, AP (Paris archives), D48E3 71), François Philibert Marquis (1883, see the article about Marquis, by Abrigeon, d’ P.), and so on. As he was over the age of seventy at the time, it was probably not Nicolas Joseph Malinet himself, but rather his nephew Henry Grimberghs who continued the business using his uncle’s name (Bloche, A., 1886, not specified). Nicolas Joseph Malinet passed away at the age of eighty-one on 27 mars 1886 at the height of his fortune, after having frequented the most famous people of his era, enriched their collections, bid for the most sought-after lots, and opened the way to a market that specialised in Far-Eastern art. His nephew, Henry Grimberghs, continued the business for a while, but moved the professional premises to 34, Rue Taitbout (ADSM, 220 JP 2119).

The collection

As a very precise post-death inventory was drawn up of the objects Malinet stored in his home and shop, it is possible—and this is somewhat unusual—to distinguish the works that were part of his dealer’s stock from those in his personal collection. The works in his private collection were sold off in part, which means that the sales catalogues can be consulted and the descriptions in these are far more detailed than those in the post-death inventory.

Nicolas Joseph Malinet’s personal collection

Part of Nicolas Joseph Malinet’s collection was sold at three sales held in the Hôtel Drouot at the auctions of Escribe and Maurice Delestre between the end of 1886 and the beginning of 1887. The first concerned the objets d’art and objetsde curiosité, which included a certain number of Far-Eastern objects (Lugt 46067); then in January 1887 the very rich collection of prints was sold (Lugt 46213), and lastly, in March 1887, more than 300 medals were sold on the art market (Lugt 46374).

The sale of objets d’art held in 1886 included a great variety of works, such as furniture, ivories, Italian and Dutch faience works, enamels from Limoges, goldsmithed objects, miniatures, and earthenware objects. The Chinese porcelains, allotted the numbers 71 to 120, seemed to be very few if one compares them to the 400 articles contained in his wife’s 1862 catalogue (see the article about Marie Antoinette Malinet, by Abrigeon, d’ P.,). Again, it is worth referring to Charles Pillet, who indicated that the ‘collection of objets de haute curiosité and Chinese objects’ was conserved by his heirs (Pillet, C., 1887, p. VII). Hence, this sale was merely a small part of the long listings contained in the post-death inventory. Nevertheless, the catalogue comprised 188 lots for a sale that totalled 16,436.50 francs.

The collection of prints mostly consisted of eighteenth-century French works, with many prints after François Boucher, Jean-Honoré Fragonard, Greuze, Nicolas Lancret, and Antoine Watteau, as well as certain prints by Chardin, Cochin, a whole series of engravings based on paintings to illustrate the tales of Jean de la Fontaine, and so on. The Renaissance was also represented by twenty prints by Albrecht Durer. The modern prints, even though they were less numerous, were also part of the collection. Malinet collected etchings—Delacroix, Barquemond, Manet, Millet, and so on—, with a majority of works by Jules Jacquemart (1827–1880). The frequent complimentary mentions in relation to the quality of a print or the presence of a margin attest to the correct management of the collection. The estimated worth of the prints and engravings when the post-death inventory was drawn up was 26,815 francs; when they were sold at auction they attained the sum of 47,559 francs (AP (Paris archives), D60E3 49).

Like his collection of prints, the collection of medals was typical of the second half of the nineteenth century, with a strong interest in Renaissance medals (Legé, A. S., 2019). The geographical provenances were varied: Germany, England, Denmark, Spain, France, Hungary, Italy, Malta, the Netherlands, Sweden, and Switzerland. While most of the lots were medals, the end of the catalogue also listed several plaques (lots 207–300) and coins (lots 301–304). The author of the preface in the sale catalogue emphasised the unique nature of this collection of medals ‘magnificently displayed in a fine piece of Louis XV furniture, on the Rue de la Chaussée-d’Antin, [where] few persons were allowed to view them’ (Lugt 46374, not specified). The collection of medals sold for a total of 14,741 francs (AP (Paris archives), D60E3 49).

However, these sales did not reveal Nicolas Malinet’s large collections of pictures. His apartment housed a remarkable collection of paintings, some of which were executed by the most popular artists of his day. One of them was the Realist painter Ernest Meissonier (1815–1891), whose works, which were often sold at auction, attained record prices (Saint-Raymond, L., 2021, pp. 280–281), as well as the painter Constant Troyon (1810–1865), another ‘safe bet’ on the market at that time (Idem, p. 278). Malinet was particularly interested in the work of still life painters such as Victor Leclaire (1830–1885), Antoine Vollon (1833–1900), Jules Félix Ragot (dates unknown), and Alexis Kreyder (1839–1912), whom he seemed to hold in high regard. He also owned many works by John-Lewis Brown (1829–1890), an English painter, engraver, and lithographer who was born in Bordeaux. His collection also included several works by Orientalist painters such as Narcisse Berchère (1819–1891), Félix Ziem (1821–1911), and Édouard Frédéric Wilhem Richter (1844–1913), as well as painters from the Barbizon School such as Narcisse Díaz de la Peña (1807–1876), Théodore Rousseau (1812–1867), Charles Jacque (1813–1894), Charles-François Daubigny (1817–1878), and Léon Germain Pelouse (1838–1891). Landscapes and seascapes were largely present in the collection, in particular those by Eugène Isabey (1803–1886), Antoine Émile Plassan (1817–1903), Eugène Boudin (1824–1898), Pierre-Eugène Grandsire (1825–1905), Stanislas Victor Edmond Lépine (1835–1892), Étienne Prosper Berne-Bellecour (1838–1910), Paul Clays (1817–1900), and so on. Realism was also well represented by the works of Théodule Ribot (1823–1891), Amand Gautier (1825–1894), Gustave Courbet (1819–1877), and so on.

Nicolas Joseph Malinet had also acquired works by less well-known painters such as Jean-Baptiste Fauvelet (1819–1883), Henri René Gaume (born in 1834), Joseph Urbain Melin (1814–1886), as well as works by young artists such as Karl Daubigny (1846–1886), the son of Charles-François. Amongst the precursors of Impressionism was Johan Barthold Jongking (1819–1891); he owned four of his works. The eighteenth century was also represented in his collection with works by Jean-Baptiste Greuze (1725–1805), François Boucher, Jean-François Hue (1751–1823), and Pierre-Paul Prud’hon (1758–1823).

The post-death inventory reveals that Malinet had family portraits executed by the painters of his times, for example that of his daughter painted by Alexis Joseph Pérignon (1886–1882).

A dealer’s inventory in 1886

The Malinet shop at 25, Quai Voltaire consisted of a ground floor, two salons, a shop and a back room, a mezzanine, a ‘storeroom at the back’ (it is difficult to know whether this was a storeroom at the back of a courtyard or whether it continued on from the other rooms) (AN MC/AND/XXVII/1427). It is interesting to note that Malinet’s personal collection and the objects sold in his shop were extremely similar. In each room, the Chinese and Japanese works were complemented by porcelains from Saxony, medals, French and Dutch paintings, and Indian miniatures, all housed in eighteenth-century-style furniture. A brief scan of the inventory indicates that extra-European objects accounted for approximately half of the valuable objects and consisted predominantly of Chinese porcelains (more than 200). With regard to painting, most of the works were by French nineteenth-century painters, with works of Alexis Kreyder at the top of the list.

I would like to thank Monsieur José de Los Llanos, Curator in Chief at the Musée Carnavalet—for generously sending me the Dutuit archives connected with the activity of Nicolas Joseph Malinet—, Antoine Chatelain, and Ludovic Jouvet for their input about the collections of prints and medals, and, last but not least, Elizabeth Emery, for her invaluable rereading.

Related articles

Collection / collection d'une personne

Personne / personne