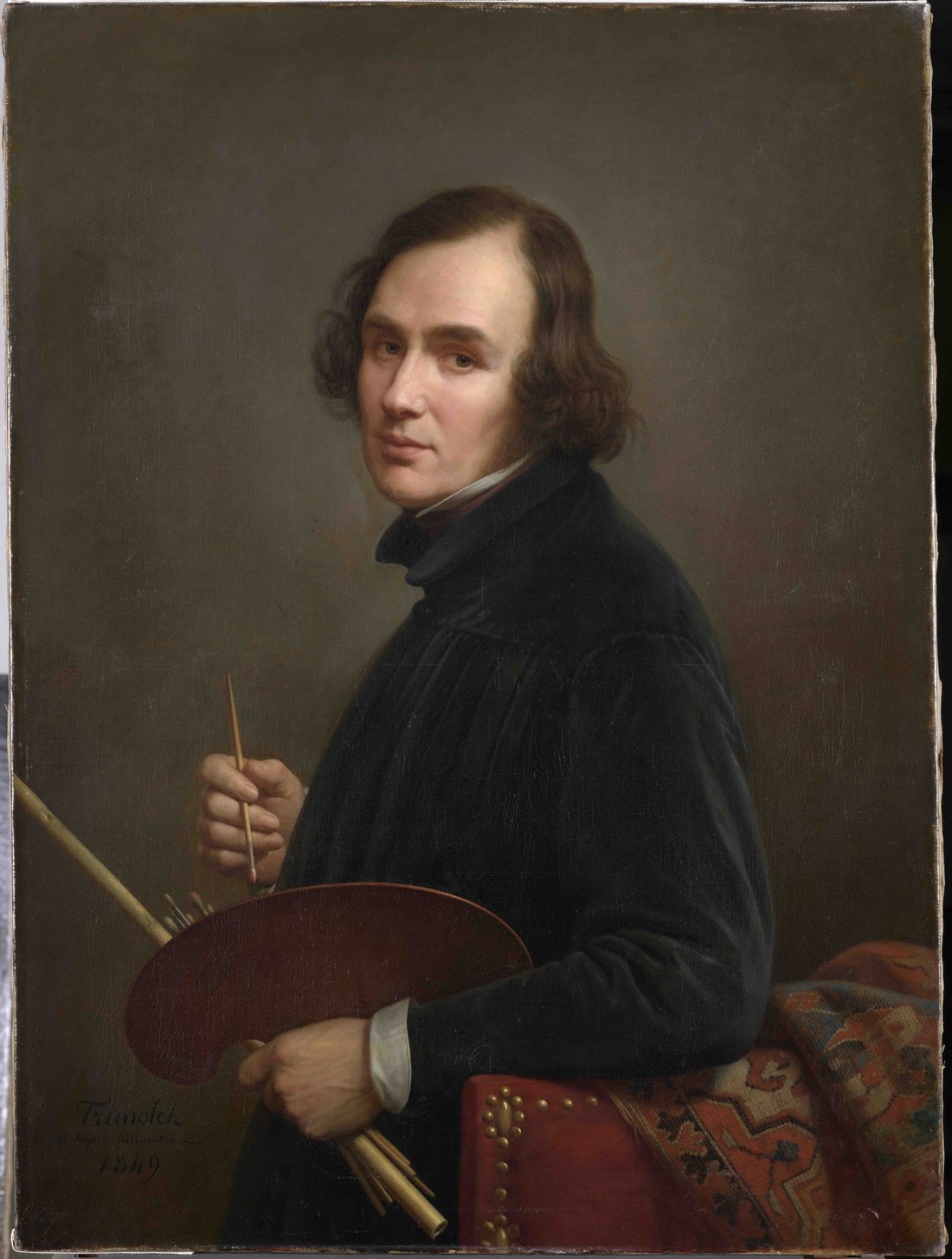

TRIMOLET Anthelme and Edma (EN)

A Painter and Engraver from Lyon

The painter and engraver Anthelme Claude Honoré Trimolet was born on May 18, 1798 (AM Lyon, registre des actes, 23/09/1797-20/09/1798, acte no 150,coté 2E/88) in Lyon, rue Raison (now rue Jean-de-Tournes, 2nd district). He died on December 17, 1866 (AM Lyon, registre des actes, 23/06/1866 – 31/12/1866, acte no 3432, coté 2E/708), also in Lyon, at the Hôtel des Princes, rue Saint-Dominique (2nd arrondissement). An autobiography published in 1850 in the Revue du Lyonnais (Trimolet, A., 1850) traces the artist’s career and also reveals his passion for collecting which earned Anthelme Trimolet the nickname of the "digger" among theart connoisseurs of Lyon.

Coming from a family of craftsmen, Anthelme Trimolet was the son of Gabrielle Jourdan and Jean-Louis Trimolet, first a silk manufacturer, then an embroidery designer who ended his career as a simple "draughtsman" and tried his hand at the decorative painting of flowers on metal. Anthelme Trimolet attended the École spéciale de dessin de Lyon from the age of ten and was, in 1808, one of the first students of the École impériale des Beaux-Arts de Lyon, training under Pierre Révoil (1776-1842) and Fleury Richard (1777-1852). This apprenticeship with the great proponents of "troubadour" painting had a decisive influence on his style, steeped in 17th century Dutch painting, and his predilection for the historical genre and the portrait. Receiving several awards during his training (Hardouin-Fugier, E., 1986, p. 265), the artist received the Laurier d’Or prize in 1815, which exempted him from military service. Trimolet’s artistic education was deepened by visits to the cabinets of connoisseurs in Lyon and beyond (in Provence in the 1820s [petit carnet de notes de Trimolet et Carnet de croquis, inv. T 1513-3, Archives of the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Dijon] and in Languedoc around 1840), as well as travels to Paris in 1817 (Trimolet, A. 1850, p. 41) and Germany in 1845 (Moureau, F., 2004), where he discovered museums and the great masters, while working as a teacher of drawing at the Collège royal de Lyon as of 1820 (until 1830).

The painter was only twenty-two years old when he first exhibited at the Paris Salon: in 1819, his painting Messieurs Eynard et Brun dans l’intérieur d’un atelier de mécanicien (Lyon, Musée des Beaux-Arts, inv. A 33) was awarded a gold medal. This success opened the way to several prestigious commissions: a portrait of the Duc de Berry, never realised, and a historical scene, Les députés du Concile de Bâle présentant la tiare à Amédée VIII (1831) for the Prince of Carignan in Turin. The Lyonnais painter exhibited at the Salon of his native town from 1827 and sent works to the Paris Salon until 1853. Despite a career devoid of official orders, the list of works drawn up by the artist (AM Lyon , 65II/129) and, following him, his biographer Aimé Vingtrinier in La paresse d’un peintre lyonnais (Vingtrinier, A., 1866, p. 11-12), testifies to an abundant production, supported by a large clientele within the bourgeoisie, in Lyon and sometimes even in Paris (Hardouin-Fugier, E., 1986, p. 265).

Painting and Collecting

Throughout his life, Anthelme Trimolet kept notebooks and indulged in various beginnings of diaries (Archives du musée des Beaux-Arts de Dijon). These "Trimolet papers" show the insatiable curiosity of the painter, who compiled historical and bibliographical research, travel stories and accounts of stays, as well as small sketches or sketches from life. They also let us perceive a personality as surprising as it is endearing, the artist lacking neither bite in the description of his contemporaries, nor self-mockery about his temperament, both inhibited and inconstant, marked by the dreaded outbursts of a profound melancholy. Above all, these abundant notations often link the two comforting passions of his restless existence: painting and collecting.

Anthelme Trimolet's artistic practice and his activity as a collector complemented and also nourished each other in various ways. Within the Trimolet cabinet, remarkable examples of ironwork (Dubuisson J., 1847) echoed the tastes of the young student from the École spéciale de dessin for "manual and mechanical work", “never happier than when [he] saw, for example, carpenters, locksmiths, tinsmiths, turners, etc, at work.” (Trimolet A., 1850, p. 40). Later, the training that he received in the studio of the painter (and prolific collector) Pierre Révoil encouraged his search for paintings and drawings from the Dutch school, and also certainly directed his curiosity towards the Middle Ages, with a predilection for furniture and silver work, which serve as models for the decoration, allegedly authentic or even realistic, of historical scenes (preparatory sketches for the paintings Henri IV, Sully et Gabrielle d’Estrées, inv. TS 1931 et Amédée VIII recevant la tiare, inv. T 496, see Hatot N., 2010). In addition, the artist's production in the field of engraving and his experimentation with techniques of great variety (Hardouin-Fugier E., 1986, p. 268) are not unrelated to the importance of his collection of prints, which already included "a suite of more than a thousand choice pieces" at the end of the 1840s (Dubuisson J., 1847, p. 332). Finally, his activity as a restorer of paintings (notably for the city of Lyon and its museum in the Palais Saint-Pierre) and his shrewd interest in pictorial technique further melded the two spheres of collecting and artistic vocation. Sitting on the Commission of the Musée de Lyon for more than four decades (until 1862, see letters from Anthelme Trimolet addressed to the President of the Commission, dated November 19 and 23, 1862, Archives du musée des Beaux-Arts de Dijon, Aa 11), he published "Réflexions sur les matières employées par les peintres" a few months before his death (Trimolet A., 1866). This exercise in restoration may have given rise to the idea that he sometimes intervened on paintings from his own collection, now kept in Dijon (Magnin J., 1914, p. 18), showing a liberal attitudetowards the authenticity of the works, which the collector did not hesitate to adjust and supply with medieval furniture, gold work, or enamelware (Jugie S., 2006 and Hatot N. 2010).

A Collecting Couple

The beginnings of the Trimolet collection date back to the mid-1820s (letter from Martin-Daussigny, curator of the Musée de Lyon, to the President of the Commission des Musées de Lyon, dated December 20, 1866, Archives du Musée des Beaux-Arts de Dijon, Aa 11). It coincided with the marriage of the artist and his pupil, the painter Louise Agathe Edma Saunier (1802-1878), on September 9, 1824 (AM Lyon, registre des actes, 15/07/1824 -29/12/1824, acte no 969, coté 2E/221). Born in Lyon on October 12, 1802 (AM Lyon, registre des actes, 23/09/1802 - 23/09/1803, acte no 138, coté 2E/104), Edma Saunier was the only daughter of Marguerite Clotilde Roccofort and Edme Saunier, wealthy landowners in Saône-et-Loire (estate of Saint-Martin-sous-Montaigu where Edma died in 1878, see AD 71, death register, 1873-1882, act no. 8, listed 5 E 459/9) and Burgundy. At the time of their marriage, Anthelme's wife had a life annuity of 6,000 francs from her father and 2,000 francs from her mother (Hardouin-Fugier, E., 1986, p. 266). Some 20 years later she inherited the fortune and property of her parents, after the deaths of her father in 1840 and of her mother in 1845. In 1866, the will of Anthelme Trimolet (Étude de Me Joannard, Lyon, November 19, 1866) gives the measure of his wife's income and leaves no doubt about its importance in the constitution of the collection: at up to approximately 6,000 francs per year (from 1858 to 1866), these revenues were “used to pay for the major part of the furniture, sculpted or not, ancient or modern, books, paintings, engravings, drawings, enamels, finally works of art of all kinds, artistic or not, which furnish the apartments.” Anthelme Trimolet took care to specify that “this task was carried out with the consent of [my] wife and to satisfy tastes that we both shared” (AM Dijon, 4R1/140, testament d’Anthelme Trimolet). These indications support testamentary provisions that gave Edma Trimolet exclusive ownership of the collection assembled by the couple and thus prevented their daughter, Agathe Anne Philomène Béatrix from having any inclination to sell the collection. Agathe was born in Lyon in 1837 and was the wife of Alfred de la Chapelle (AM Dijon, 4R1/140, marriage contract), who died in 1868, then of Jean-Jacques Cluas, whom she married in 1869. After her husband’s death, Edma Trimolet continued to buy furniture, works of art, paintings, and sculptures (posthumous inventory of Edma Saunier, veuve Trimolet, “comptes et factures relatifs à Lyon”, Archives du musée des Beaux-Arts de Dijon, Aa 11) and respected his wish to preserve their collection from dispersal: in 1878 she bequeathed to the city of Dijon a set of more than 1900 items, intended to form a museum perpetuating their names (AM Dijon, 4R1/140, testament d’Edma Trimolet, 1878).

Monsieur Trimolet's Cabinet

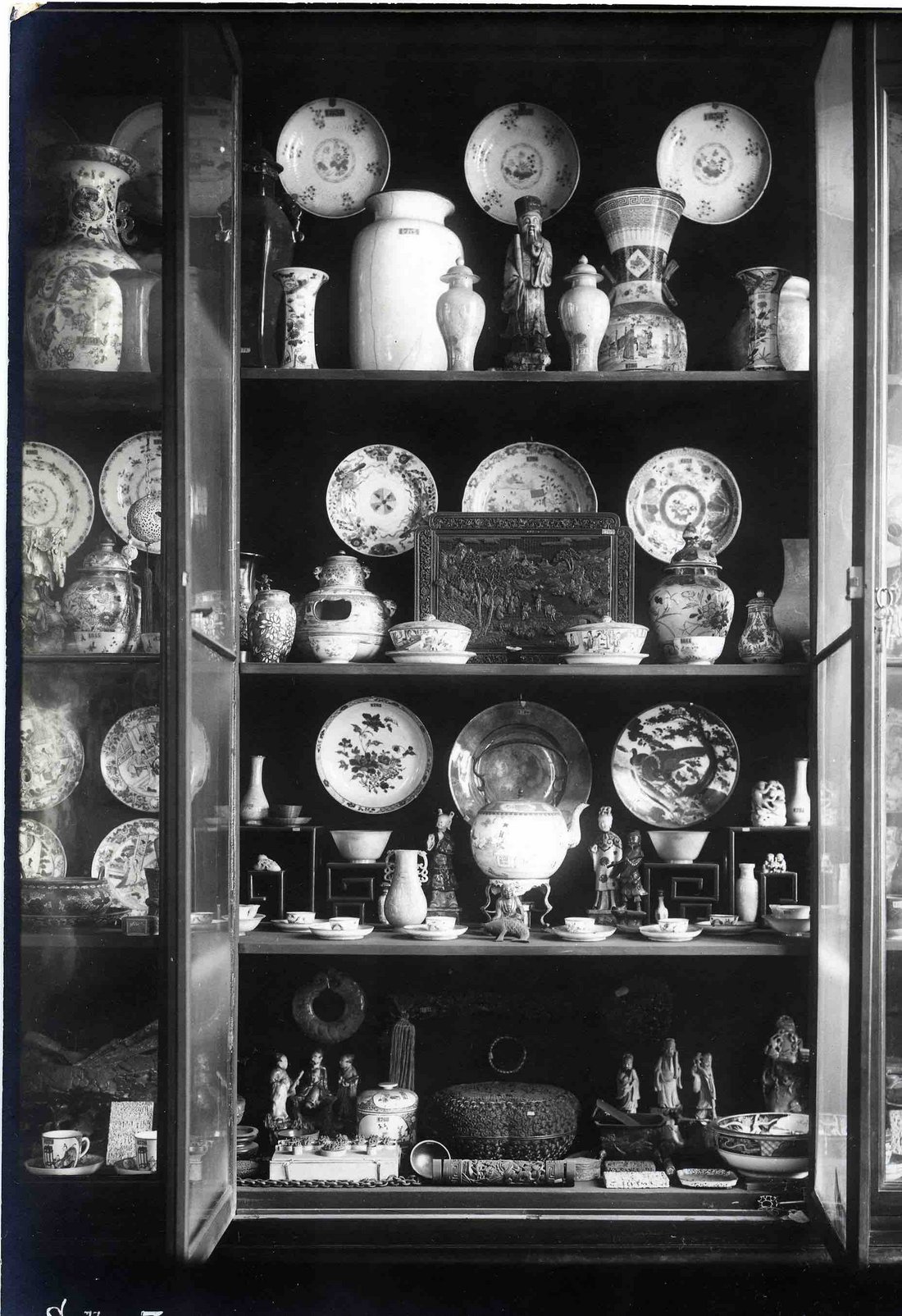

The huge collection put together by the painter Anthelme Trimolet and his wife Edma in their Lyon home in some ways perpetuates the tradition of cabinets of curiosities. Formed for the most part between the mid-1820s and Anthelme Trimolet’s death in 1866 (letter from Martin-Daussigny, curator of the Lyon museum, to the president of the Commission des musées de Lyon, dated December 20, 1866, Archives du musée des Beaux-Arts de Dijon, Aa 11), it drew both its eclecticism and didactic vocation from this model from centuries past: "Not only has Monsieur Trimolet sought to bring together all that can establish the history of art and industry in their different degrees and their different periods, from the simple forms of their earliest times to phases of the most brilliance, but he has also only allowed that which bears the stamp of perfection of his time into his collection. It is with this scrupulous care that he succeeded in forming a sort of almost complete genealogy of art” (Dubuisson J., 1847, p. 331-332). In 1847, the description in the Revue du Lyonnaisconfirmed the already remarkable extent of the "Cabinet de M. Trimolet": more than 1,000 prints (burin engravings and etchings by painters); drawings and paintings by old masters, predominantly from the Venetian and the Dutch schools; “several good pieces of sculpture”; numerous ivory diptychs; a collection of magnificent Limousin enamels (reliquaries, salt cellars and cups, caskets, pax tablets (baisers de paix), medallions); goldsmithery and jewellery, glassware from Venice, ceramics from Palissy: a representative set of ironwork (wallet clasps, knives, daggers, sword hilts, helmets and halberds, pistol grips, tobacco rasps); carved furniture (credences, cabinets, chests); and finally, some antiques.

Lyon’s Emblematic Collection of Curiosities

Through its broadly understood technical diversity and pronounced taste for the Middle Ages, the appearance of the Trimolet cabinet in the middle of the 19th century was not dissimilar to other collections in Lyon during the same generation (those of the painter Pierre Révoil, the pharmacist and archivist Antoine Barre [1787-1850], or the architect Jean Pollet [1795-1839]), formed by connoisseurs with limited resources (for the contrast with wealthy collectors of the upper middle class, see Garmier J.-F., 2003) and often connected with the world of silk, for example Jacques-Antoine Lambert (1770-1850) or Jean-Baptiste Carrand (1792-1871). Anthelme Trimolet's correspondence, like his production of portraits (Vingtrinier A., 1866, p. 11-12 and Trimolet A., 1850, p. 123), testifies to an entourage intimately linked to the world of curiosité in Lyon, of which his teacher and friend Pierre Révoil was a central figure (letter from Révoil to Trimolet dated March 31, 1832, Archives du musée des Beaux-Arts de Dijon, Aa 11). Anthelme Trimolet’s closest friends also included the amateur Antoine Barre and the critic Alexandre-Humbert Chatelain (1778-1852), with whom he shared the "monomania" of collecting (letters from Trimolet to Chatelain, dated May 26, 1841 and August 7, 1842, Archives du musée des Beaux-Arts de Dijon, Aa 11). He painted portraits of Chatelain and of other collectors such as the draftsman and engraver Balthazar Alexis (1786-1872), the judge François-Aimé Capelin (1786-1856), the silk manufacturer Didier Petit, and even the connoisseur Jean-Marie-Henri Germain (1784-1867). These personalities and the richness of their cabinets of curiosities appeared in the catalogues of the major exhibitions of the Palais Saint-Pierre in Lyon at the end of the 1820s and 1830s, where we also find the Trimolet collection (exhibition of 1837, nos. 21, 24 , 45, 46, 47). Completing this Lyon circle, Anthelme Trimolet’scorrespondence and notebook also includes more distant and more prestigious collectors: the Count of Sommariva (1762-1826), whom he met in 1819 (Musée des Beaux-Arts de Dijon, carnet inv. 1513-1); François Sallier (1767-1831), whose collection he discovered in Aix-en-Provence before it was dispersed in 1831 (see a small notebook from 1830, Archives du musée des Beaux-Arts de Dijon); and Alexandre-Charles Sauvageot (1781-1860) whose cabinet he visited in 1852 (letter from Trimolet to Sauvageot dated May 12, 1853, Archives du musée des Beaux-Arts de Dijon, Aa 11).

While Anthelme and Edma Trimolet took advantage of their trip to Bavaria in 1845 to visit a few antique dealers at various stages of their journey (see Moureau, F., 2004), most of their acquisitions were made from Lyon merchants, and more rarely at public auctions (letter from Révoil to Trimolet, dated March 31, 1832, Archives du musée des Beaux-Arts de Dijon, Aa 11), notably during the dispersal of the collections of Didier Petit in Paris in 1843 and of J.C. Sivous, silk broker, in Lyon in 1860 (Garmier, J.-F., 2000, p. 251). In the posthumous inventory of Edma Trimolet (Archives du musée des Beaux-Arts de Dijon, Aa 11), the account registers for the house in rue Saint-Joseph (from 1836 to 1877) show the extent to which the Trimolets were loyal customers of the antique dealer Sicard (quai de l'Hôpital), the curiosities dealers Botton (place Bellecour) and Verdier (quai de l'Hôpital), and even the goldsmith Grognier-Arnaud (quai Saint-Antoine), while Millet provided a "Chinese lantern", Bailly "a pair of Chinese lamps", and Gagneur (also spelled Gagneure or Gagnieur) lacquers, ivories and pieces of furniture from Asia.

A "Trimolet Museum" in Dijon

Despite this context of burgeoning curiosité in Lyon, the city nevertheless lost the Trimolet collection. Following the death of Anthelme Trimolet in 1866, the curator of the Lyon museums, Edmé-Camille Martin-Daussigny (1805-1878), endeavoured to convince the painter’s widow to consent to a donation for the benefit of his native town (letters from Martin-Daussigny to the President of the Lyon Museums Commission, dated December 19 and 20, 1866, Archives du musée des Beaux-Arts de Dijon, Aa 11). But in the end, the city of Dijon won out: Edma Trimolet chose to bequeath them her collection (estimated at a value of 750,669 francs) on the express condition that it be exhibited in a specific museum bearing the donors’ names (AM Dijon, 4R1/140, will of Edma Trimolet dated August 25, 1875). The city of Dijon officially accepted this bequest on October 10, 1878, but did not come into possession of the collection until May 1880 following a transaction which put an end to the lawsuit brought by the collectors' only daughter, Béatrix Trimolet, wife of M. Cluas (AM Dijon, 4R1/140).

Installed in four rooms on the first floor of the Dijonmuseum, the "Musée Trimolet" was finally opened to the public on October 31, 1880. The 1883 catalogue lists 1919 items ranging from Antiquity to the 19th century (Gleize, É., 1883), without however reflecting the extent of the collections of drawings (540 numbers) and engravings (2429 numbers), inventoried starting in the 1950s. The areas of predilection evoked in the description of the cabinet in 1857 were thus simultaneously consolidated and expanded (Garmier, J.F. 2000),European art objects forming, after the graphic arts, the largest part, with more than 730 entries (ivories from the 5th to the 14th century, cameos and engraved stones, enamels from the 12th to the 17th century, goldsmiths, watches, jewellery, 16th and 17th century glassware, earthenware and porcelain, caskets, arms and ironwork). This was followed by numismatics (340 coins and medals) and 130 antique objects; finally, for the rest of the European collection, paintings and miniatures (155 numbers), sculptures (35 entries), and 90 pieces of furniture (from the 16th to the 18th century). While several major pieces of Islamic art slipped into the collection of ceramics and glassware (a large enamelled and gilded glass bottle from Mamluk Egypt, inv. CA T 995), the last sections of the catalogue devoted to "works of oriental manufacture" and "various objects from Africa and Oceania" evoke more specifically these distant cultures towards which the collectors’ insatiable thirstwas also directed. Adorning in particular the living room, dining room, and "a room serving as a Chinese museum" (counting 123 objects according to the posthumous inventory) of the house in rue Saint-Joseph, Asian objects were among the 266 lots in the catalogue of 1883, and were divided according to materials and techniques of creation: jades, steatite, ivories, wood, bronzes, lacquers, enamel and goldsmithery, painting, porcelain and stoneware from China, porcelain and earthenware from Japan, and furniture. The outbreak of the Second World War, followed by the completeoverhaul of the museum’s layout, led to the dissolution of the unitary ensemble over the course of a history of European arts and typological galleries, thus putting an end to the "museum within the Museum" (Gonse, L., 1904, p. 160) and sending most of the Asian works in the Trimolet collection into storage.

Related articles

Personne / personne

Collection / collection d'une personne

Personne / personne