LECLÈRE André (EN)

Biographical article

André Leclère was born on January 21, 1858 in Paris, at 64, rue du Cherche-Midi. He was the son of a printer-bookseller, Henri Louis Emmanuel Leclère, and Céline Marie Hélène Gerard, without profession. He trained as an engineer and specialised in geology. Pierre Termier (1859-1930), who studied plate tectonics in the Alps, evokes the memory of a "simple", modest, kind and upright man, but also "wise", intelligent, "a hard worker who never knew how to rest", "who seemed to know everything", and whose "great quality was to know thoroughly what he knew". Of a curious nature, André Leclère was "in turn a chemist, agronomist, geologist, petrographer, micrographer, always a zealous civil servant, ready to lavish his time and his advice, with absolute disinterestedness", again according to Pierre Termier (Dougados J. and Termier P., 1916, p. 33).

Railway Opportunities

André Leclère received the title of Student Engineer of Mines after two years of studies at the École polytechnique. He continued his training at the École Supérieure des Mines starting October 1, 1880. From Ordinary Engineer of Mines 3rd class, on November 1, 1883, he rose through the ranks, moving to 2nd class on July 1, 1886, and to first class on November, 1894 , in order to finally be promoted to chief engineer 2nd class on September 16, 1899. First in Rennes, he began service in Le Mans.

After his professorship at the École des Mines de Saint-Étienne, where he taught chemistry and metallurgy, André Leclère took advantage of his post in Chalon-sur-Saône to "become familiar with the practice of coal mining" (Dougados J. and Termier P., 1916, p. 31). Havingbecome affiliated with the service du contrôle du Chemin de fer de l’Ouest in previous positions, he began working in Marseilles, where the PLM was within his remit. As Inspector General Jules Dougados (1855-?) points out in his speech at his funeral, André Leclère quickly understood the boon to his career represented by the development of the railways. Also, at his request, he was put "in the service of the Compagnie des chemins de fer économiques du Sud-Est as an engineer responsible for construction and operation" (Dougados J., 1916, p. 31). However, the engineer quickly abandoned industrial mercantilism "to return to science, towards which his tastes led him", as pointed out by the inspector (Dougados J. and Termier P., 1916, p. 31). He thus returned to Le Mans, where he worked in the service of the geological map of France.

The Mission to China: Preparatory Studies for the Construction of the Yunnan Railway (雲南)

In 1897, he became involved with the Ministry of the Colonies, having been approached by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Gabriel Hanotaux (1853-1944), for a special mission in Tonkin and China. In charge of the mission, he joined the Guillemoto technical mission for the construction of the Yunnan railway, which had already been established.

The bridge and road engineer Charles Marie Guillemoto (1857-1907) was the leader of a mission responsible for determining the route of the future Yunnan railway line, which was to link Tonkin to central China. A preliminary prospecting mission, which had been on the ground since February 1897, had made it possible to determine the various routes to be considered; its results were condensed in a "Very Succinct Note on the Lines of Penetration into southern China" addressed to the Minister of the Colonies, André Lebon (1859-1938), on June 1, 1897. Subsequently, on September 27, 1897, the colonial administration decreed the creation of the mission to be of general interest.

André Leclère represented the scientific dimension of this mission; he was more specifically responsible for sounding the ground and drawing up a geological map of the area under consideration. The aim was to study the mineral resources of southern China, in particular Yunnan and its border regions, Guangxi (廣西) and Guangdong (廣東), but also to determine the exploitability conditions of the various deposits. A study of the populations of this mining basin, whose many riches were already assumed, was also planned, with an evaluation of the work value of potential workers in the region. Leclère was ordered to remain discreet in his field investigations. His mission was confidential, to the Chinese government as well as his compatriots. Leclère’s writings thus evoke a slow and unescorted march, to avoid arousing the suspicions of the mandarins.

The engineer embarked on December 5, 1897, aboard the liner Armand Béhic, named after one of the founders of the Compagnie des Couriers Maritimes. Feverish, he arrived in Hanoi on January 6, 1898, and joined Guillemoto. They both embarked on the Red River aboard a small boat belonging to the Compagnie des Correspondences Fluviales, which took them to Lao Cai, where they arrived on January 20. Leclère began his prospecting with an exploration in the Tonkin region, around Lào Cai, with Théophile Pennequin (1849-1916), commander of the military territory concerned. A second stage, carried out with the help of Lieutenant-Colonel of Marine Artillery Charles Gosselin (1852-1929), led him to cross the Sino-Annamite border at Wenlan (文瀾). They had to undergo an attack of miners of Tse-men-tong [unidentified place], which does not cause serious damage. On February 1, to visit Wenlan, André Leclère joined forces with the members of the mission - Kerler, conductor of the bridges and roads, Surcouf, second lieutenant of cavalry, and artillery captain Bourguignon, who took care of photographic views, in addition to astronomical and meteorological observations. At the end of the month, they were joined by the engineer Guillemoto. The following month, the mission worked on the development of the Wenlan-Lào Cai section. On March 11, 1898, a first report reported on the progress of the technical mission to China. On March 12, Guillemoto reported incidents caused by local rebellions, stirred up by the Chinese authorities in Yunnan, whose aim was to stop the work of the mission. On the 13th, Leclère gave his opinion on the geological situation of the area crossed so far. Finally, the Franco-Chinese treaty of April 10 granted France the land for the railway between Tonkin and Kunming (昆明). The following month, the mission thus pushed on to the capital of Yunnan, which was reached on June 6.

André Leclère surveyed the surrounding region and took leave of Guillemoto on August 10, 1898. On the 24th, he sent a new report to the ministry. The mission left Dongchuan (東川), after a visit to the copper mines, and reached the mouth of the Yalong (雅礱), via Huili (會理), in the Liang shan district (凉山), in southern Sichuan (四川). On October 12, the mission crossed the Blue River at Mongkou [unidentified town]. It then followed the Mandarin Road, passing the southern end of the Liang Shan and reaching the town of Dali (大理) on November 10, where Leclère had a chance encounter with reserve cavalry captain Bruno de Vaulserre (18?-19?), cousin and brother-in-law of one de Wendel, industrialist of the metallurgy in eastern France, associated with the Compagnie du Creusot. Bruno de Vaulserre left the Bonin mission under obscure circumstances. The explorer and diplomat Charles-Eudes Bonin (1865-1929) had been suspected of taking advantage of his position and mistreating the natives. Leclère defended de Vaulserre from any involvement and seconded his insistence that the region was in the grip of revolt. The mission thus continued in his company. The officer would deal with issues of dissemination of the knowledge acquired to the general public. The mission undertook the study of the Blue River basin, of which de Vaulserre made the topographical survey. It reached Kunming on November 29, rectifying the position of the Heijing Saltworks (黑井) along the way. On January 19, 1899, the engineer and his companion arrived in Xingyi (興義) and continued their journey through Guiyang (貴陽), Guilin (桂林), and Nanning (南寧). From there, they returned to Hanoi, where their mission ended.

This last step was an opportunity for André Leclère to explore the regions targeted by the English in their plan to penetrate China from Burma. It is important to note the climate of tension in which the mission evolved. The race for concessions between England and France, which saw the Davis mission travel through the border territory in November 1898, was tough.

Highlighting the value of the provinces of southern China, the engineer's observations aroused controversy even before their publication. As Leclère was bound to secrecy, these were certainly empirical positions stated before the start, which he would confirm further on the ground. He suffered harsh attacks from his colleagues, since he was downgraded on the promotions list. Discouraged and contemplating resignation, he opened up to Guillemoto, of whose response the archives contain no trace (ANOM, GGI 6632).

Scientific Results of the Mission and Solicitation for Commercial Expertise

André Leclère disembarked in Marseille aboard the liner Ville de la Ciotat on July 16, 1899. Having exceeded the terms of his contract, he obtained from the Ministry of the Colonies an extension for the examination of the samples (ANOM, INDO AF 42). On December 10, 1899, he completed a new report entitled "Législation des Mines en Chine au point de vue de la pénétration industrielle". He was also put in charge of several negotiations with mining organisations. Paul Doumer (1857-1932), Governor General of Indochina from 1897 to 1902, asked him to help the Yunnan Mining Syndicate, then under the chairmanship of the Count of Bondy, with a view to exploiting the deposits of the province. On March 15, 1899, the Syndicate applied to the Zongli yamen (總理衙) [a government agency then responsible for China's foreign policy] for the concession of "all the deposits of tin and coal now unexploited in the region of Ko -tiou [Gejiu (個舊)]", against the advice of André Leclère. Negotiations failed, leading to the dissolution of the syndicate on November 9. Subsequently, a request was made to Leclère to get in touch with the General Traction Company, directed by the chief engineer of the Mines Albert Olry (1847-1913), which benefited from the support of the Ministries of Foreign Affairs and Colonies. Leclère drew his attention to deposits of varying values.

End of Career at Le Mans

His mission completed, he was granted three months of convalescent leave. On May 3, 1900, he returned to his duties within the Ministry of Public Works, and on June 1, he was assigned to the Mineralogical District Service of Le Mans, where he ended his career. He became integrated into the society of this city. On March 3, 1886, he was received into the Society of Agriculture, Sciences and Arts of Sarthe as a full member, and became its vice-president in 1903.

During the first months after taking office, he persevered in the work of popularising the scientific data collected during his mission in China. He intervened within the framework of the 2nd Congress of French Geographical Societies, at the session of August 22, 1900. He thus won the esteem of his supervising minister, who supported his observations. While he had drawn a salary from the budget of the Ministry of Public Works, with which he wasaffiliated as an engineer, André Leclère had had to finance part of his mission himself. In recognition of his work, he was made a chevalier de la Légion d’honneur, by decree of January 23, 1901, on the proposal of the Minister of the Colonies Albert Decrais (1838-1915). Leclère presented his results to the Académie des Sciences and other learned societies, such as the Société de géographie de Paris. Bruno de Vaulserre communicated with readers of Le Tour du Monde. Conferences with image projections vividly presented his observations, which he was now authorised to disclose. He had taken care to request this authorisation from the authorities when he received an invitation from Prince Roland Bonaparte (1858-1924), president of the Paris Geographical Society, to give a lecture on the water geography of Upper Tonkin and China at the Congress for the Advancement of Science (ANOM, INDO AF 42). The subject had evolved in the meantime. Thus, during the 26th session of the Congress organized in 1900, André Leclère evoked his exploration in southern China and presented his observations on the region’s geological and geographical constitution (1900b and 1900c).

It should be noted that the national printing office had been requisitioned on June 26, 1901 for night work by Paul Doumer, for the printing of the "Rapport sur les ressources minières du Yunnan", in fact contravening the labor regulation law. To the Director of the Printing Office, taken aback, the Minister of Justice, Ernest Monis (1846-1929), represented the urgency of the situation, being a "printing of interest to the security of the State". This shows the sensitivity of the data presented in this book. On July 4, 1901, the director declared that he was still awaiting a formal justification that would allow him to "cover the responsibility of the national printing office" (ANOM, INDO AF 42).

André Leclère finally published his "Étude géologique et minière des provinces chinoises voisines du Tonkin" in the Annales des Mines in two installments, in October and November 1901, republished the following year by Dunod.

In Le Mans, he devoted himself to a quieter job, consisting of the analysis of samples in the city laboratory. He became interested in new areas. The discovery of fossil algae in many sediments modified "a large number of geological determinations" (Leclère A., August 1913). According to his peers, this latest research had a great impact on the Académie des sciences and was moreover a "new interpretation, unique to him" (Bulletin de la Société d'agriculture, sciences et arts de la Sarthe, 1915, p. 231). He also became interested in the genesis of granite. He is said to be the author of "scholarly communications", the "great authority" attributing to them "appreciable value" (Bulletin de la Société d'agriculture, sciences et arts de la Sarthe, 1915, p. 231). The geological mission carried out in China certainly contributed to increasing this scientific aura. He also spoke on other subjects, delivering "an overview of the economic transformations that may result from current events east of the Mediterranean" (Bulletin de la Société d'agriculture, sciences et arts de la Sarthe, 1915, p.229).

In 1913, with the support of Pierre Termier, André Leclère joined the Association Amicale des élèves de l’école des Mines. The war suspended his ongoing studies. Although his age prevented him from fighting on the front, he was mobilised to the rear and charged by the Ministry of War with preparing "the works for the supply of drinking water and the evacuation of waste water for the development of the Auveurs camp” (Dougados J., 1916, p. 32). On October 15, 1915, he died suddenly at the age of fifty-eight, an "indirect victim of the war", according to the Inspector General (Dougados J., 1916, p. 33).

Leclère, André. « Étude géologique et minière des provinces chinoises voisines du Tonkin ». Annales des Mines. 20, octobre 1901, pl. X, fig. 5.

The collection

The explorer traveled more than 6,000 km from Tonkin to China. His field investigation was thus based on several working materials, to be analysed later, upon his return to mainland France.

Collecting Raw Research Materials

The collection of mineralogical samples represents an important part of the sources considered by the geologist, who also relied on oral testimonies, collected from local mandarins, as well as on photography. The latter was part of the process of research and information gathering. While we understand the method of processing soil and rock specimens, it is more difficult to trace the genesis of the photographic practice.

Processing Raw Materials

During the mission, samples were regularly sent to Guillemoto, who kept them in his residence in Hanoi. The boxes were then handed over to the Ministry of the Colonies, through the Governor General of Indochina. Six boxes were opened on August 23, 1899, under supervision of members of the mission - André Leclère, Bruno de Vaulserre, and Guillaume-Henri Monod (1875-1946), deputy head of the Geological Service of Indochina, who for a time participated in the expedition (late 1898 – early 1899) – accompanied by a scientific delegation, made up of Tannière, delegate of the Magasin central and Antony, delegate of the Service géographique des missions. Seventeen other crates were set aside and transported to the Pavillon de Flore, at the Louvre, for examination and cataloguing, with the prospect of an exhibition at the Société de géographie de Paris y (ANOM, INDO AF 42).

The correspondence remains elusive on the methods of conservation and packaging of the photographs. However, on reading the published articles, and in particular the report published in the Annales des Mines, photography played an important role in the argument, considered as demonstrative of the facts stated. A hundred images illustrate the articles.

Photographic Practice within the Guillemoto Mission

The function of photographer was certainly an integral part of Guillemoto's technical mission, with the role played by Bourguignon and Roques, named soldier-photographer (ANOM, GGI 24722). On the other hand, the practice is avoided in the archives. We do not know the number of cameras carried by the mission. No doubt there were several, if only to equip the two constituent branches.

The device belongs to the Service géographique of the ministère des Colonies, while the plates were provided by the mission (ANOM, GGI 6632). The shooting was a collective process, Bruno de Vaulserre contributing, especially in his solitary expedition on the banks of the Blue River. André Leclère took care of developing the negatives, but could notshoulder the cost of printing the positive prints on paper alone. For these manipulations, he asked for a credit of 250 francs from the head of the geographical service of the ministry, which was granted on October 7, 1899 (ANOM, INDO AF 42).

Differential Analysis of Materials

The aim was to fix the age of the deposits observed and to draw up a new geological map of the Yunnan region and its bordering regions. However, André Leclère claimed independent expertise, wishing to "provide the French Administration with bases for independent assessment of industrial competitions" (ANOM, INDO AF 43 / 116). Also, to guarantee the authenticity and viability of the results, and to ward off any criticism, the consequences of which it had to suffer in spite of everything, he entrusted the samples to two separate laboratories: the testingoffice of the Ecole Supérieure des Mines and the laboratory of the Compagnie des Mines de Nœux, acting blindly, without knowledge of the origins. The results were then discussed by a group of scientists and presented in the form of four notes to the Académie des sciences.

Photographs were foreign to this process. While they respected a logic of deduction, they did not conform to this standard of work ethic. These were taken care of by the geologist himself.

The Contributions of Photography to Geology

In the natural sciences, photography has clear applications. The botanist and photographer Eugène Trutat (1840-1910), author of a manual on La Photographie appliquée à l’histoire naturelle, was convinced of this. Photography is there judged as an "indisputable authority", endowed with "mathematical precision" (Trutat E., 1884, p. VI). Geology is a field science. It aims to reconstruct, through the study of rocks, the formation of the landscape. In this, stratigraphy is a major component. Photography responds logically to this interest granted to the visible. Photography thus constitutes an additional analysis tool, in addition to maps, plans and landscape profiles.

Systematisation of the Gaze

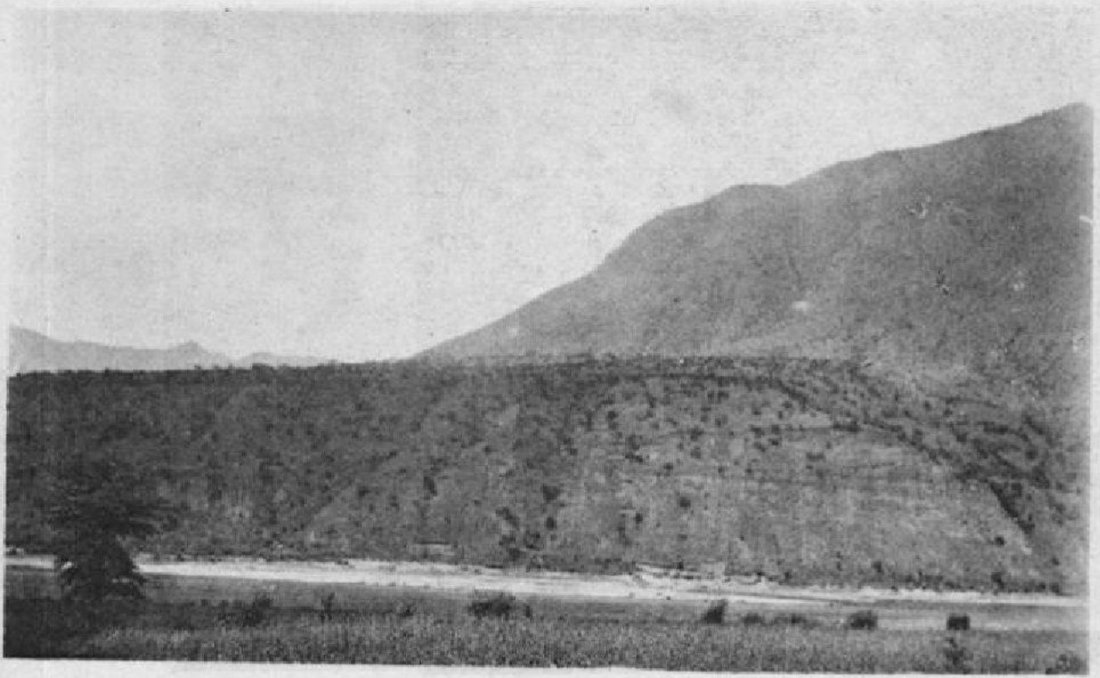

André Leclère dissected the landscape that unfolds before his eyes and set up different approaches: landscapes, close-ups, frontal views, bird's-eye views. The photographs are presented as geological surveys, close to schematic geological cross-sections. Likewise, the gaze seems to conform to a certain number of codes. It is thus possible to identify a systematisation of the observation, highlighting the horizontality of the landscape, composed of its different strata, the photographer seeking to gain distance, and therefore height, while striving to vary the points of view. The construction remains rigorous and meets the needs of the geology.

A Depopulated Landscape

André Leclère meticulously observed the the peaks encountered on the road to Xinyi (信宜), in Guangdong, and crossed the karst region, from which he retained the image of raw rocks. These rocks were sculpted naturally in the vicinity of Lufu (鹿阜), the province of Yunnan, district of Kunming, a remarkable geological phenomenon also visible in Guizhou (貴州), Guangxi, and the region of Chongqing (重慶). He noted the topography of the Heijing salt deposits in Yunnan, located on the banks of the Longchuan jiang (龍川江). He was also interested in the coal deposits, marking the landscape in the places of production – the forges, blast furnaces, and ovens. The photographs of these mining basins turn out to be strangely empty, in the absence of the workers who would bring them to life. The confidential nature of the mission and the resulting precautions certainly explain this deserted aspect. The accent is placed rather on the landscape, its configuration, and its modelling. The photographs give us an overview in fragments. The study of this iconographic set must take into account the framing given in the publications, endorsed by a publisher, which undoubtedly differs from the original framing, chosen by the photographer.

The Issue of Original Photographs

While the documents brought back from the mission are the property of the ministry that commissioned them, the photographs should in principle have been placed in the archives. However, this was rarely the case; they remained rather in the possession of their author. After showing them at the Indochina pavilion at the Universal Exhibition of 1900 in Paris, along with the topographical surveys and mineralogical samples, mistakenly classified in the category "Samples of Tonkin wood", André Leclère asked:“What to do with the photographs?" There is probably no longer any question of any public exhibition. To whom should I give them?” (ANOM, INDO AF 42).

Related articles

Personne / personne

Collection / collection d'une personne