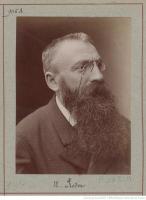

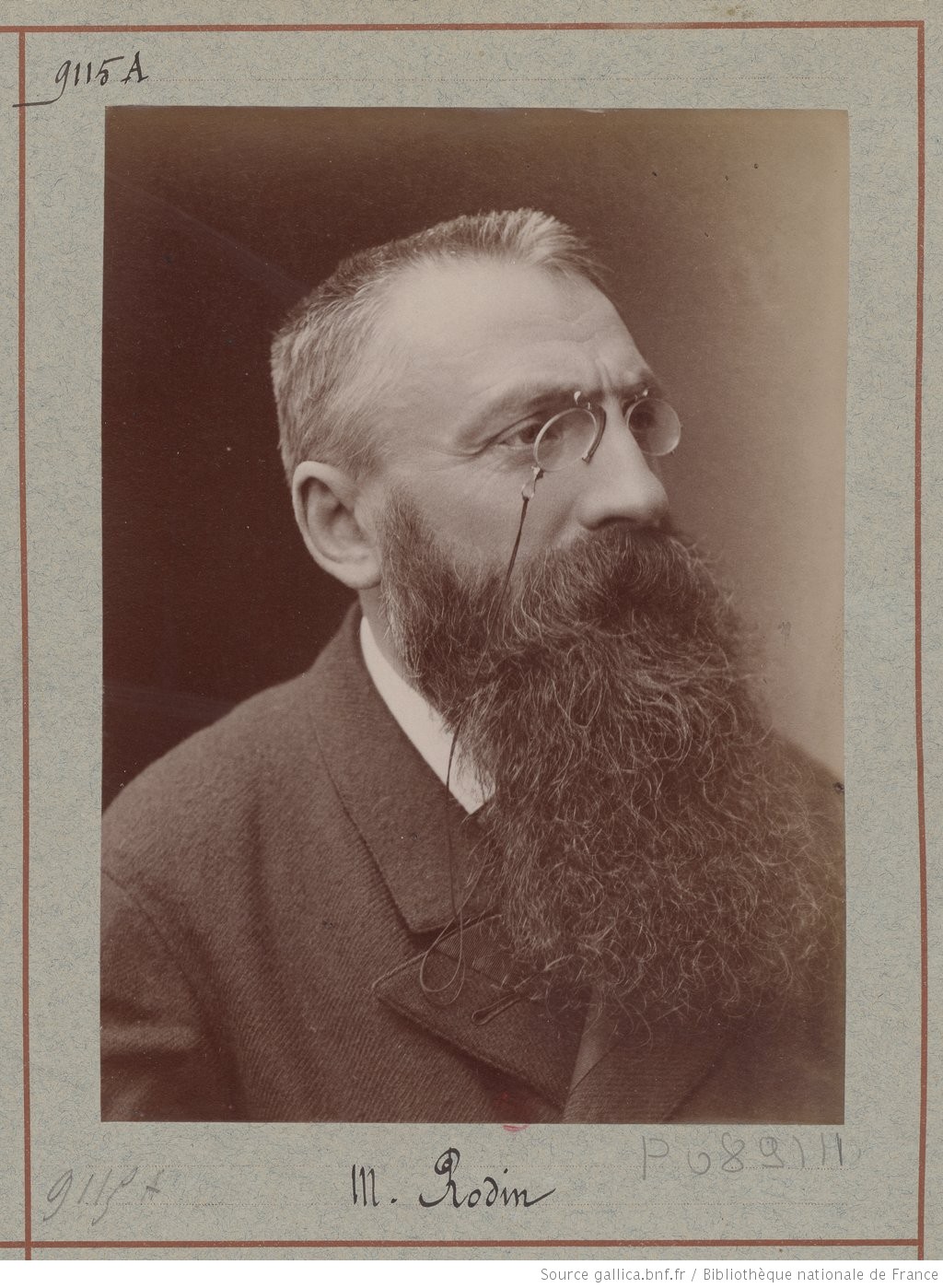

RODIN Auguste (EN)

Biographical Article

Auguste Rodin was born on November 12, 1840 in Paris. He was the son of Jean-Baptiste Rodin (1803-1883), originally from Normandy, and Marie Cheffer (1807-1871), from Lorraine. At age 14, he entered the École spéciale de dessin et de mathématiques, known as the "Petite école", located on rue de l'École de médecine, which he left in 1857. At the same time, he attended evening courses at the Manufacture des Gobelins, where he worked from the live model. He discovered sculpture in 1855 and entered a studio after receiving a bronze medal in drawing.

From 1864, Rodin collaborated with the sculptor-decorator Albert Carrier-Belleuse (1824-1887) whom he joined in Belgium in 1871; this cooperation ended the following year. However, Rodin remained in Brussels until 1877, working on various architectural decorations (Palais de la Bourse, then Palais des Académies). This stay was punctuated by two trips to Italy (May-June 1875 and end of 1875-March 1876). The plaster of The Age of Bronze (L’Âge d’airain) was exhibited in 1877 at the Cercle Artistique de Bruxelles, then in Paris; this work triggered a controversy, as Rodin was accused of moulding from life, but the scandal helped to establish his fame.

Back in France, called by Carrier-Belleuse, he entered the Manufacture de Sèvres in June 1879, where he worked more or less sporadically until 1892.

In 1880, the State gave him a commission for The Gates of Hell (La Porte de l’Enfer) in bronze, for the future Musée des Arts décoratifs. The museum was inaugurated in 1905, but without Rodin’s work, which was never completed since the commission was canceled the previous year. In 1885, the city of Calais commissioned him to build the Monument des Bourgeois de Calais, inaugurated in 1895.

In 1887, he was a member of the sub-commission of the Exposition universelle of 1889; he was also named Chevalier de la Légion d’honneur (LH//2779/35). In 1889, he was a founding member of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts and a member of the jury for the Exposition universelle. That same year, he received the commission for a Monument à Victor Hugo; the first project was refused, and the sculpture was finally installed in the garden of the Palais Royal. From 1891 until 1895, Rodin carried out two projects simultaneously, multiplying the studies and models for a seated Victor Hugo and a naked Victor Hugo intended for the Pantheon. In 1891, the Société des Gens de Lettres commissioned a Monument à Balzac from him, which was refused by the committee in 1898. He was promoted to Officier de la Légion d’honneur in 1892 (LH//2779/35).

A stone's throw from the Champ de Mars where the Universal Exhibition of 1900 took place, Rodin presented his sculpted and drawn work in a space known as the "pavillon de l'Alma". It was visited by a large public, including collectors as well as Japanese artists who discovered the work of Rodin, then unknown in Japan. This pavilion would be reassembled in Meudon the following year and became his workshop-museum; on his plans, the future Musée Rodin in Meudon would be built, inaugurated on May 29, 1948.

In 1903, he was named Commandeur de la Légion d’honneur, and Grand Officier in 1910 (LH//2779/35).

The Thinker (Le Penseur), created in 1880, was exhibited in its plaster and large format version in 1904 at the International Society in London.

In 1909, a first project of donation to the state was envisaged by Rodin, a project which would lead in 1916 to the creation of the museum dedicated to his work and integrating all of his collections. The Musée national Auguste Rodin was inaugurated in 1919.

Rodin died on November 17, 1917 in Meudon.

Japan in Rodin's Work versus Rodin and Japan

Rodin's affinities with Japanese art were of various kinds. From 1885-1890, he frequented figures of Japonisme such as Albert Kahn (1860-1940), Georges Clemenceau (1841-1929), the travellers Henri Cernuschi (1821-1896) and Félix Régamey (1844-1907), Edmond de Goncourt (1822-1896), and the regulars of the "Grenier d'Auteuil", Félix Bracquemond (1833-1914), Philippe Burty (1830-1890), Gustave Geffroy (1855-1926), and Octave Mirbeau (1848-1917). He exchanged artistically with painters and collectors of ukiyo-e prints, including Claude Monet (1840-1926), Camille Pissarro (1830-1903), Jules Bastien-Lepage, James Mc Neil Whistler (1834-1903), Frits Thaulow (1847-1906), or even Raphael Collin (1850-1916). It should be remembered that Rodin acquired, no doubt on the advice of Octave Mirbeau (1848-1917), Le Père Tanguy by Van Gogh (Paris, Musée Rodin, inv. no. P.07302).

His attraction to Japanese theatre was evident at the Exposition universelle of 1900 where he attended the show La Geisha et le Chevalier. He was seduced by the play and expression of his interpreter, the famous Japanese actress Sada Yacco (川上 貞奴) (1871-1946). As for dance, he was impressed by the gestures and expressiveness of Hanako 花子 (Ôta Hisa, 大田 ひさ, 1868-1945), encountered in Marseilles during the Exposition coloniale of 1906. From 1907-1912, she posed for a series of drawings and sculptures (58 heads and masks).

He was even more fascinated by a material long used by the Chinese and then the Japanese: ceramic stoneware. Balzac or Jean d'Aire would come to life in this material thanks to Paul Jeanneney (1860-1920).

While these links with Japanese art are easy to trace, it is more difficult to characterise this relationship with regard to the graphic and plastic design of his work.

We can attribute as a mark of a successful Japonisme, that is to say in its last stage - assimilation - his nudes drawn from memory which he defined in 1900 as "snapshots varying between Greek and Japanese", as reported by C. Judrin in his article "Le Japon et la naissance du dessin moderne de Rodin " (Rodin le rêve japonais, 2007, p. 11). The outline that defines the volumes and the rapid freehand execution that enlivens the movement evoke the mastery of the Japanese draftsman; according to his expression, it is "Japanese art with the means of a Westerner" (Judrin C., p. 13).

Even during the artist's lifetime, critics differed as to Rodin's rapprochement with Japanese aesthetics and the Japanese titles with which he bestowed or annotated several drawings - such as Beau dessin japonais (D.4526), Vase jap[onais], Psyché japonaise, Japonaise (D.4591), Théâtre japonais (D.3970) – are less iconographic or stylistic references than precise and furtive images of his constantly active mind.

At the end of the 1890s, Rodin was asked by his friend Octave Mirbeau to "illustrate" Le Jardin des supplices published in 1902 by Ambroise Vollard (1866-1939). It was not a matter of illustrating but rather of graphically transposing this novel, a mixture of voluptuousness and violence, murder and blood, pity and pain, qualities found more in the 10 drawings not integrated into the volume that in the 20 line drawings included in the book and reproduced in lithography by Auguste Clot (1858-1939). More expressive and powerful, the drawings reflect the erotic character of the work - whose action takes place in China and are entitled Supplice japonais (D.3958) and Jardin des supplices (D.4258). In these works, Rodin endeavours to represent the various tortures: either a nail driven into a foot, or female hair from which a trickle of blood flows, staining the ground red (D.3958). The latter, annotated by Rodin "low/low/low/ … (fifth act/torture/Japanese, referring to the description of a scene from Mirbeau: "I live defending the entrance..."): “An octopus, from its tentacles, embraced the body of a virgin and, with its ardent and powerful suction cups, pumped love, everything, in the mouth, in the breasts, in the belly. And I believed that I was in a place of torture and not in a house of joy and love” (p. 158-159). Fin-de-siècle literature and Japanese xylography intertwine; Mirbeau's description refers to Katsushika Hokusai's famous erotic print 葛飾 北斎 from the album Kino-e no Komatsu (c. 1814). This print also inspired Rodin for a watercolour drawing entitled The Octopus (La Pieuvre) (D.1526), just as suggestive as, but more stylised and abstract than, Japanese xylography.

"I have drawn all my life, my art rejoins that of Japan", wrote Rodin in 1910 to Arishima (1883-1974), director of the review Shirakaba.

Numata Kazumasa 沼田 一雅 (1873-1954), Nakamura Fusetsu 中村 不折 (1866-1943) and Oka Seiichi (1868-1944), painting and sculpture students who admired the sculptor, were received by the "Master" in Meudon on October 6, 1904; Rodin offered everyone a drawing. Fusetsu commends on his gift: “[…] for the contour of the face, he gets that beautiful line by drawing it in one stroke from the ear. As for the line of the shoulder and the line that starts from the scapula to the trapezoidal muscle, which the rest of us could only produce with great difficulty, going back to it 10 or 20 times, he traces them out of nowhere, a single stroke of the pencil” (Judrin C., p. 11). Is this "single pencil stroke" not reminiscent of the cursive drawings of a Hokusai in his collections of the Mangwa or the album Ippitsu gafu?

Similarly, Takamura Kotaro 高村 光太郎 (1883-1956), a sculptor who graduated from the Tokyo School of Fine Arts, wrote to his sculptor friend, Ogihara Morie 荻原 守衛 (1879-1910) - considering himself a pupil of Rodin in 1907, about the exhibition of drawings seen at the Devambez gallery in 1908: “A fine and strange line […]. Looking at the drawings, I felt like I felt the smell and warmth of human skin. No one in the art of the past has been able to express to such an extent the infinite charm of the female body through the morbidezza of her flesh” (Judrin C., p. 12). This idea was corroborated by Rodin's secretary, the poet Rainer Maria Rilke, evoking "an outline that takes your breath away from nature [...], lines that have never had such force of expression even on very rare Japanese sketches” (Rilke R. M., 1903).

The figures of Japonisme who admired the art of the "grand master" acted as ambassadors of Rodin's work in Japan. They spread his work by writing laudatory articles accompanied by reproductions in the magazine Shirakaba (白樺) and by practicing their art marked with the seal of modern western sculpture.

The Collection

Before becoming a collector, Rodin saw, observed, and admired the collections of his Japoniste contacts and friends, in particular that of Edmond de Goncourt, who invited him to discover his erotic prints, along with Félix Bracquemond. The writer notes in his Journal: “Rodin, who is rather faunish, is full of admiration before the women’s drooping heads [...]" (Journal, January 5, 1887, p. 3-4). But a few months later in October 1888, Edmond de Goncourt, mistaking the sculptor's intentions, reported "an intelligent and fine being, but completely blocked, closed, walled up". He adds that, in reaction to "Japanese prints of the greatest style, he looks at them for a moment, then closes them and walks away, as if fearfully saying that he does not want to see them any longer for fear of being impressed by them” (Journal, October 28, 1888, p. 171).

However, visiting in 1893 the Outamaro et Hiroshigé exhibition at the Durand Ruel gallery organised by Siegfried Bing (1838-1905) in the company of Claude Monet (1840-1926) and Camille Pissarro (1830-1903), Goncourt wrote to his son: “Admirable, the Japanese exhibition. Hiroshigé is a marvellous impressionist. I, Monet, and Rodin are enthusiastic about it […] these Japanese artists confirm our visual bent” (Camille Pissarro, 1950, Paris, February 3, 1893, p. 298).

State of the Art

From 1895, Rodin, who had settled in Meudon, began to collect Greek and Roman works and some Egyptian and Japanese objects with archaic forms, which he exhibited in the Villa des Brillants.

Today, more than 2,000 pieces are listed and kept in the museum of Meudon. They make up the "antiques" collection along with Egyptian (1,000 items), Greek and Roman objects as well as some from the Middle Ages, a few pieces from Mexico and India, and finally, works of Japanese and Chinese manufacture whose origin is difficult to determine, even for specialists. Production generally dates from the 19th century. Some objects disappeared after Rodin's death.

Well studied, the collection of Japanese prints, kept in the reserves of the Rodin museum in Paris, currently has 288 items (sheets of paper, collections of engravings, 112 India ink drawings from disassembled notebooks and preparatory drawings for engraving (hanshita-e), 15 stencils for printing patterns on pieces of fabric as well as illustrated books including Keisai soga (sketches by Keisai by Masayoshi) and Hokusai Gaen (collection of drawings by Hokusai). The prints date from the late Edo period (1603-1868) and early Meiji period (1868-1912) and illustrate familiar ukiyo-e subjects: actors, courtesans, landscapes, fish, erotic albums, and some scenes from the Sino-Japanese war (1894-95).

Among the most represented designers, we can mention Utagawa Kunisada 歌川 国貞 (1786-1865) i.e. 77 proofs), 44 Utagawa Kuniyoshi 歌川 国芳 (1797-1861), 35 Utagawa Hiroshige 歌川広重 (1797-1858), 13 Hashimoto 沌 孧 Sadahide (螧 孝 Sadahide 1807-1873), and some engravings by Utagawa Toyokuni 歌川豊国 (1769-1825), Utagawa Hiroshige III 歌川 広重 (1842-1894), Utagawa Yoshikazu 歌川 芳員 (active around 1850-70), and finally Utagawa Yoshiiku 歌幝 (芳幝1833-1904), not counting the gift of Shirakaba (see below).

As for China, it is represented with some 60 bronze objects (21 items), whether patinated, damascened, niello, or enamelled, in the form of pairs of vases (Co.197-1, Co.197- 2), figures representing the Buddhist pantheon: Kannon (Co.128) or The God of Longevity (Kotobuki) seated on a deer (Le Dieu de la longévité (Kotobuki) assis sur un daim) (Co.124), the latter used as an incense burner. The inventory of a dozen of these objects reveals the taste of Westerners for this type of import: incense burner in the shape of an elephant mounted by a child (Co.188) or that from the temple of Kannonji (Co.6361).

The netsuke (Co.132, Co.13, Co.171), 12 okimono (12 numbers) in ivory, with a Buddhist subject, underscore the dexterity of Japanese craftsmen in precisely sculpting groups of figures only a few centimeters high in a detailed way (Co.131).

In porcelain, we can cite the Paire de potiches couverte by Imari (Co.151, Co.151-2), decorated with female figurines walking under flowering wisteria, or the Paire de vases hexagonaux (Co.155-1, Co.155-2), in porcelain with underglaze relief and gilt enamels on a craquelure background. These pieces were displayed in the windows of the Hôtel Biron among other antiques and works by Rodin.

Ceramic stoneware was brought back into fashion at the end of the 19th century by the artists of Art Nouveau: Rodin appreciated its raw, rough appearance with random cracks, such as Daruma with a shoe (Daruma à la chaussure) (Co.142), standing with his arms crossed under a loose garment that undeniably evokes the Balzac monumental (S.3151) in plaster. This statuette was offered to him by the sculptor John Tweed (1869-1933) in 1898 after the scandal that year with the statue sculpture, refused.

Rodin surrounded himself with expressive wooden masks, Masque de bugaku (Co.927) or Masque hilare (Co.129) in lacquered wood, with glass eyes and hair, contrasting with the Masque au visage furieux (Co.130). Let us recall its use by Rodin from The Man with the Broken Nose (L’Homme au nez cassé) (S.1431) to that of Hanako, known as Head of Death's Anguish (Tête d’angoisse de la Mort) (Japan, Nigata Museum).

Although in the minority compared to the collections of Egyptian, Greek and Roman antiquities, objects from China and Japan found their place in Meudon from 1895, as is testified by F. Lawson, Rodin's secretary, tin 1906: "On one corner is a cupboard filled with tiny statuettes of Japanese or other origin" and confirmed, the same year, by Victor Frisch (1876-1939), Rodin's assistant: "He showed me a case of Chinese objets d’art: his words laved with tender discrimination the cloisonnés, porcelains, ivories, and carved wood of the Buddhist art. And in the neighbouring case were flowers of the arts of Japan: exquise booklet, prints, pottery; disc of ivory filet, seamless ball within ball of daintily carved filigree, beyond telling how they had become ensphered there" (quoted by B. Garnier in the exhibition catalogue Rodin et le Japon, “Les japonaiseries d’Auguste Rodin”, p. 126).

Acquisitions

The invoices and receipts kept in the museum's archives make it possible to follow Rodin’s acquisitions from Parisian dealers. During the Exposition universelle, he acquired two albums from a set of 20 volumes relating to Japanese paintings "Shinbitaikan" [sic] (invoice dated October 24, 1900 on the letterhead of the dealer Kiyoshi Ganda). From 1906, 1908, and especially after 1910, his purchases accelerated.

It would be tedious to quote in detail all the acquisitions made by Rodin, an undertaking for which Bénédicte Garnier, who was in charge of the collection of "antiques" for the catalog of the exhibition Rodin et le Japon, was responsible. Regarding Japanese woodcuts, let us summarise for the year 1908: six acquisitions between February and November from the antique dealer Gaudens-Fourcadet at Japon artistique, three albums of prints for 250 francs; at Bénard: an album, 250 Francs, two albums (G.7560) and an erotic roll (G.7562), all for 356 francs. He went three times to Léon Isidore and acquired 20 prints for 800 francs, three prints for 20 Francs, and two Japanese notebooks, price not noted.

As for the objects acquired for the most part between 1910 and 1913, he went to Seris four times between February and December 1910. That same year he left Pierre-Ferdinand Monel with a bronze divinity, two masks on paintings, and a mask with hair (Co.129); on December 29, he bought two vases from Léon Isidore and a pair of white Japanese vases with light figures (Co.151-1 and Co.151-2); at Paul Terce’s, a bronze incense burner identified as the god of longevity (Co.124). For the years 1912 and 1913, the names of Joseph Brummer and Junca should also be mentioned.

However, many acquisitions remain anonymous. From 1912, purchases slowed down especially as the installation of the collections at the Hôtel Biron – occupied by Rodin in its entirety since 1911 – was completed with a view to the creation of a museum based on the idea of bringing together his works and his antiques in order to show all the influences that had nourished him.

Donations

Collectors who admired of the great sculptor sent him gifts as thanks, such as Doctor Linde of Lübeck who, having acquired sculptures for his park after the 1900 exhibition, offered him two prints by Kitagawa Utamaro 喜多川 歌麿 (1753-1806) in 1902. His letter of June 12 comments: "I don't know if the Japanese master is from the circle of your artist friends. […] I have said to myself that you, mon cher maître, must love this art […].”

The painter Morie Ogihara, who became a sculptor after seeing The Thinker (Le Penseur), offered him two prints by Harunobu in 1907: “[…] choosing the paintings of Suzuki Harunobu – Japan's greatest artist for the expression of intimate beauty of a woman - we thought it was especially suitable for the artist.” This missive - written in the studio of art historian, painter, and essayist Walter Pach (1883-1958) - is co-signed Morie Ogihara/Walter Pach. These prints are listed under the numbers G.7453 and G.7456.

Sometimes these were less gifts than solicitations equivalent to bargaining chips. In February 1912, Mr. Mizuochi, antique dealer in Osaka, sent him this letter: “I take the liberty, Master, of offering you 20 old prints and two volumes of drawings. A small drawing drawn by your hand or a simple word of answer coming from you, would be the height of my happiness. Let me hope that you deign to acquiesce to my request.” Rodin responded by sending him a drawing.

The collection of Japanese prints is enriched significantly in terms of importance thanks to the donation of the members of the review Shirakaba, a monthly literary and artistic review published between 1910 and 1923. To pay tribute to the great sculptor on the occasion of his 70th birthday, they published a special issue in November 191l and offered him a set of nishiki-e prints. Mushakōji recalls their choice: "Naturally we don't have enough money to buy extraordinary ones. We had nevertheless acquired a little more than 20 of good quality and, around August, we finally sent them to Rodin, with some prints preciously preserved and offered on this occasion by certain members of Shirakaba, i.e. a total of 30 works. Ikuma Arishima 有島 生馬 (1882-1974), director of the magazine lists them: six Utagawa Toyokuni, four Utagawa Hiroshige, three Eisen 渓斎英泉 (1790-1848), one Taigaku 美術 (1805-1825), one Shôtei Hokuju 昇亭北寿 (1763-1824), a Katsushika Hokusai, a Toyokuni II (1777-1835). The print by Kitagawa Utamaro on a yellow background, Toji zensei, bijinzoroi Tamaya-nai Komurasaki (The Beauties of the Day), and that by Utagawa Toyokuni, Yakasha butai no Sugata-e Hamamuraya (Image of an actor on stage, Hamamuraya), stand out from the set for the excellent state of preservation and for the illustration of classical themes: the high-ranking courtesan or the famous actor.

Touched by their attention, Rodin responded by praising art based on the deep observation of nature: "I have looked at them for a long time and at various times, some are perfect masterpieces of grace, simplicity, and strength. And, to show them his esteem, ask them to accept three small bronzes (° Une petite ombre, 2° Tête de gavroche parisien, 3° Buste de Mme Rodin) (cat. Japon, F. B., p. 197). He offered them an exhibition of his graphic work in Tokyo in 1913, considering Japan to be the country of drawing; the project was never realised.

Conclusion

Rodin's Far Eastern collection, which he started late, at the end of the 19th century when quality objects were already becoming scarce, is characterised by its variety and diversity of media. It appealed to his imagination beyond objective reality and translated the two focal points of his creation, sculpture and drawing, independently of one other. From the perspective of working material and sources of inspiration, Japanese and Chinese art share clear affinities with Rodin’s work.

Rodin’s collections of antiques were the subject of his fourth and last donation (October 25, 1916), accepted with difficulty by the French State, as it was considered to be of lesser quality. In 1899, the critic Arsène Alexandre defined the status of these objects "which a great museum would perhaps disdainfully reject, but which suffice as a pretext for his imagination, whose beauty he knows how to share with you, and which is complemented in an unexpected and charming way by his naive eloquence" (Garnier B., p. 51).

The collections contributed to the creation of an encyclopaedic and educational museum at the service of young artists with a view to their training and education. As a testament, Rodin declared: "You who seek to be officiants of beauty, perhaps you will find here the product of a long experience" (Rodin A., 1924, p. VII).

Related articles

Collection / collection d'une personne

Personne / personne