CHAVANNES Édouard (EN)

Biographical Article

Social Environment

Emmanuel-Édouard Chavannes, known as Édouard Chavannes, was born on October 5, 1865 in Lyon, into a Protestant family. Born Swiss, he became a naturalised French citizen around the age of 20. Édouard Chavannes was the second son of Frédéric-Émile Chavannes (1836-1909) and Blanche Dapples (1841-1865), who died a month after his birth. Five years later, his father married Laure Poy (1849-1900?), with whom he had eight children. Chavannes spent a few years of his childhood with his paternal grandmother in Lausanne, then returned to Lyon where he lived with his father and stepmother. (Chavannes É., 1882, p. 1-34; Cordier H., 1917, p. 114-147.)

Education and Occupation

At the age of 18, Chavannes went to Paris to pursue higher education. As a graduate of the Lycée de Lyon, he passed the baccalaureate in July 1883 and then entered the preparatory class at the Lycée Louis-le-Grand. He was admitted to the École normale supérieure in Paris with the specialty of philosophy in July 1885, and took courses there simultaneously in history and archeology. In 1886, he began studying Chinese at the École des Langues orientales vivantes and at the Collège de France. In July 1886, he obtained the license of letters and, in November, the baccalaureate of sciences. In 1888, he was received second in the aggregation of philosophy and, in November of the same year, he received a degree in Chinese language from the École des Langues orientales vivantes. At the end of 1888, Chavannes was first appointed to the lycée of Lorient, and then swiftly applied for a mission to China with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to study the Chinese language and country. At the beginning of this stay, he wrote about ten articles on China, published in the "Lettre de Chine" section in the newspaper Le Temps. He began his translation of the Shiji 史記 and carried out his first scientific mission, during which he chose to study the Han bas-reliefs of Wu Liang ci in Shandong (MAE, Archives diplomatiques, Personnel 1e sér., vol. 914, no 72 CHAVANNES Emmanuel Édouard, Lettre au Ministre des affaires étrangères, Pékin, 21 septembre 1890, Annexe). He married Alice Dor (1868-1927), daughter of an ophthalmologist from Lyon, while on leave in France in 1891. Chavannes initially wanted to become a diplomat, which would have allowed him to stay in China and continue his sinological research. But, on April 29, 1893, at the age of 28, he was appointed professor at the College de France to the chair of "Chinese Language and Literature and Tartar Manchu". At the end of this year, he began his teaching, which remained a primary occupation until the end of his life. From 1904, he co-directed the magazine T'oung Pao with Henri Cordier (1849-1925), which was his other major occupation. Between March 1907 and February 1908, he carried out his second mission in China, in Manchuria and northern China. During this time, Chavannes collected a large quantity of sources in several formats and observed the China of his time. After his return to France, he took up teaching duties in the Religious Sciences section of the École Pratique des Hautes Etudes for four years (1908-1912). On January 29, 1918, Chavannes died in Paris, from an attack of uremia, in full possession of his heightened intellectual faculties and at the promisingbrink of rich productivity.

Chavannes devoted much time to his students and trained a generation of great sinologists in France and abroad. These included his French pupils Paul Pelliot (1878-1945), Henri Maspero (1883-1945), Marcel Granet (1884-1940), and Paul Demiéville (1894-1979) as well as his Russian pupil Vassili Alekseev (1880- 1951), who played an important role in the development of Sinology.

Chavannes was a member or collaborator of several scientific institutions, such as the Société asiatique, the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, the Bibliothèque nationale de France, the École française d’Extrême-Orient, the musée Guimet, and the musée Cernuschi, as well as private organisations. He participated in their scientific research, their commissions for the publication of journals, and particularly in the purchase of Chinese books and objects.

During his life, Édouard Chavannes was very active: depending on the circumstances, he was in turn a journalist, diplomat, sinologist, scientific editor, and even protector of Chinese heritage. What stands out the most when considering the whole of his work is not only its volume, but also the variety of fields covered: history, epigraphy, archaeology, religion, art, and science. The wide range of modes of intervention should also be underlined: translation, critical study, reviews, notes, and epistolary correspondence. Chavannes published a total of 14 works, about 100 articles and more than 200 reviews between 1890 and 1917, to which can be added several posthumous publications.

Travels

In his sinological studies, Chavannes measured the inadequacy of the elements that can be provided by texts as sources and argued for the need to explore the archaeological aspect through surveys and direct observations in the field (Ghesquière J., 2005, p. 10-11). He carried out two scientific missions in China. As an attaché authorised to the French Legation in Beijing from 1889, he requested his first scientific mission to China during his leave in France in 1891. He carried out this mission after his return from France between November 10, 1891 and May 19, 1893 (Lettre de la Légation de la République française en Chine au ministre des Affaires étrangères, le 2 décembre 1891, Pékin, Ministère des Affaires étrangères, Archives diplomatiques, Personnel 1e sér., vol. 914, no 72, CHAVANNES Emmanuel Édouard). His second mission to China took place between April 14 and November 4, 1907, not including the days of the travel between France and China (Chavannes É., 1907, p. 561, 710). His route was determined by "archaeological considerations", in order to find important monuments of the past. During his second trip, Chavannes not only traveled routes already known to European travellers, but also tried a route never previously taken by a Westerner (Chavannes É., 1908, p. 503-504). The main sites that Chavannes visited and studied can be divided into two categories: the first have an epigraphic and artistic value, such as the Wu Liang ci 武梁祠, the funerary temples of Confucius and Mencius, the forest of steles (Beilin 碑林), Longmen Grottoes 龍門, Yungang Grottoes 雲岡and Taishan 泰山; the latter have archaeological value, such as the imperial tombs of Koguryo and the Tang dynasty or the caves of Yungang and Longmen. Chavannes sought what new observations could be made in the sites already known or visited by his predecessors, and brought fresh insight by opening epigraphic and archaeological research on them.

Involvements in the Artistic World

Chavannes contributed to the study of art and displayed great literary and artistic sensitivity from his youth. He performed plays at school and at home, visited exhibitions, especially of painting and sculpture, and often expressed his feelings and comments on works of art. He was also passionate about dance, more classical than modern. This preference for classicism was also manifested in the subjects and materials of his sinological research (Letters of Édouard Chavannes to his parents between 1883 and 1885, kept by the Chavannes family). According to Louis de La Vallée Poussin (1869-1938), a Belgian Indian scholar specialising in Buddhism, the École Normale Supérieure had instilled profound artistic and humanisticsentiments in Chavannes (1918, p. 150).

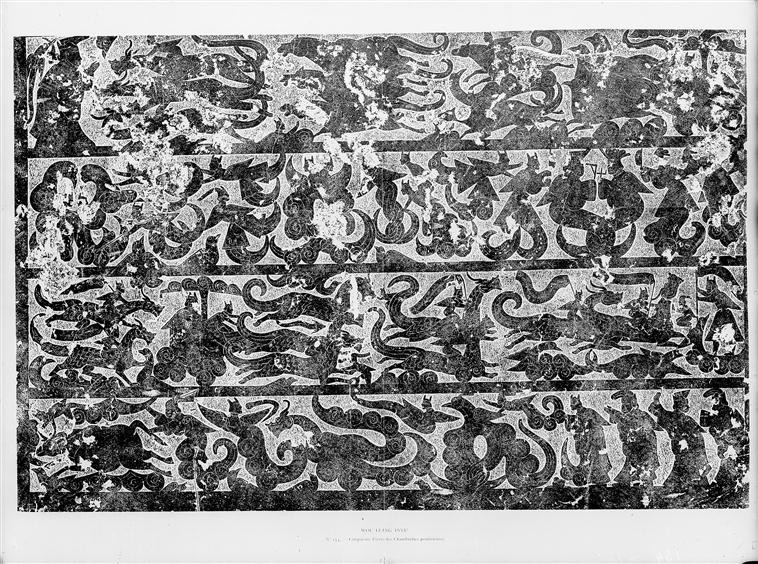

This sensitivity to art was consistent with Chavannes throughout his career. During his trip to China in 1907, he visited and photographed offering chambers in Shandong and Henan, where bas-reliefs had been carved by the Han peoples. He also reproduced them in print form. He visited and photographed the two great Buddha caves, of Yungang and Longmen, as well as the Zhaoling and Qianling imperial tombs of the Tang. The results were published in the two photo albums of Mission archéologique dans la Chine septentrionale (1909). He also collected popular Chinese New Year images (nianhua年畫) and bought books on Chinese art (1901; Eliasberg D., 1978).

In his iconographic research, Chavannes' interest was mainly in the Han bas-reliefs and the Buddhist sculptures of the Yungang and Longmen caves. He discussed the artistic aspect of these works, giving a detailed description of the monuments: size, appearance, style, scene, gesture and decoration, colour, etc. The origin, size, and content of each work were carefully noted and, even more remarkably, he explained the motifs based on ancient literature, to which he provided precise references. In so doing, he conferred a new archaeological and artistic value on the sculpted stones of ancient China (Chavanne É., 1893, 1909, 1913, 1915). He organised the first exhibition of Chinese paintings at the Musée Cernuschi from April to June 1912 in partnership with Raphaël Petrucci (1872-1917) and Henri d'Ardenne de Tizac (1877-1932), and published a book on this exhibition (Goloubew V., 1914a, 1914b). He also wrote articles on the paintings and sculptures of China presented in exhibitions and museums, providing information on the works involved (Chavannes, 1904a, 1904b, 1906, 1909, 1913). Yet Chavannes was careful to avoid expressing comments of an artistic nature, probably since he didn’t consider himself a specialist.

According to Henri Cordier, for a long time, Europeans only had vague notions of Chinese art and knew very little concerning sculpture (Cordier H., 1914, p. 671). Chavannes was the first historian of stone sculpture in China. He also distinguished himself from Chinese scholars in epigraphic study by his iconographic research. According to Michèle Pirazzoli-t'Serstevens (2010, p. 129), the Chinese scholars and collectors who had studied the inscriptions focused their attention on checking and correcting the texts, but showed little interest in other research areas.

One of Chavanne’s students, Berthold Laufer (1874-1934), an American of German origin, followed the path of his master with regard to Han funerary sculpture. Chavanne was interested in his student’s work and gave several reviews. Raphaël Petrucci, sinologist and art historian of the Far East, began to learn Chinese epigraphy under Chavannes’s direction in the 1890s. Bonded thereafter by a deep friendship, they collaborated to write La Peinture chinoise au musée Cernuschi (avril-juin 1912) (Goloubew V., 1914a).

With regard to popular Chinese New Year images, Chavannes noticed early on this particular type of print, which had become popular at the end of the Qing dynasty and published an article in 1901 (republished in the form of a brochure in 1922) entitled "De l’expression des vœux dans l’art populaire chinois". In this article, he uses folk images as sources to discuss Chinese folk art. Engraved on wood, these images were pasted on the doors of houses at New Year's time. The depicted subjects touch upon gods, opera scenes, daily life, folk legends, human activities, and political events. Alekseev, who traveled for four months in China with Chavannes, was most likely influenced by his teacher and later became passionate about this type of art. Today, the custom of nianhua has disappeared in most parts of China, and the surviving collections of Chavannes and Alekseev, as well as those of other enthusiasts or specialists, are all the more valuable for having been gathered at a time when interest in folklore among Chinese sinologists and art aficionados was rare.

The Collection

In his sinological studies, Chavannes focused on the insufficiency of the elements that texts can provide as sources and argued for the need to explore archaeological aspects through surveys and direct observation in the field (Ghesquière J., 2005, p. 10-11). He carried out two scientific missions in China, during which almost all his collections were accumulated.

The exploration of China corresponded to a trend of the time. Chinese archeology was then totally unknown to the entire world, and according to Henri Cordier, it was the French who gave it scope (1914, p. 671). At the end of the 19th century, various national committees began to organise a series of explorations in the Tarim basin, succeeding each other almost without interruption until the mid-1910s. Between 1891 and 1894, the mission of Jules Léon Dutreuil de Rhins (1846-1894) was carried out in East Turkestan (now Xinjiang) and Tibet. In 1895 and 1896, Charles-Eudes Bonin (1865-1929) traveled to Southeast Asia and Gansu as well as Mongolia (Malsagne S., 2015). Paul Pelliot, between 1906 and 1908, carried out his famous missions in northwestern China and recovered the Dunhuang manuscripts. Between 1899 and 1902, a first Swedish expedition to the Lob-nor Lake region in Xinjiang was led by Sven Hedin (1865-1952). Then, on the English side, Aurel Stein (1862-1942) went to Chinese Turkestan three times in 1900-1901, in 1906-1908, and in 1913-1915. On the Prussian side, the Museum für Völkerkunde in Berlin sent Albert Grünwedel (1856-1935) and Georg Huth in 1902-1903, Albert von Le Coq (1860-1930) in 1904-1905, Grünwedel and Le Coq in 1905-1907 and Le Coq in 1913-1914 in the northern Tarim Basin, around Turfan and Koutcha. The Japanese and Russians also carried out missions around Turkestan and Dunhuang. From 1902 to 1914, Kōzui Ōtani 大谷光瑞(1876-1948) and his disciple Tachibana Zuichō 橘瑞超(1890-1968) organised three archaeological missions in Central Asia, where they excavated, bought, and collected a large quantity of precious manuscripts, documents, and antiquities, such as ancient books and manuscripts from Dunhuang (Sang B., 1996, p. 34). P. K. Kozloff (1863-1935) and Sergei Oldenburg (1863-1934) undertook field investigations at Dunhuang in 1914. In addition to Central Asia, the number of French exploring Asia grew: we can cite the missions of Sylvain Lévi (1863-1935) in India and Japan between 1897 and 1898, then in Eastern Asia between 1921 and 1923. Others, like the mission of General Henri d'Ollone (1868-1945) in southwestern China between 1906 and 1909, aimed to study independent populations such as the Lolos, an ethnic group almost unknown to explorers and researchers. Aimé-François Legendre (1867-1951) and Captain Noiret, in the 1910s, also traveled to the regions of Yunnan and Sichuan. The missions of Victor Segalen (1878-1919) in China, accompanied by Jean Lartigue (1886-1940) and Gilbert de Voisins (1877-1939) in 1914-1917, should also be mentioned.

These missions are as successful as they are contested when it comes to a large collection of precious objects built by the explorers, such as those of Aurel Stein and Paul Pelliot. According to Michèle Pirazzoli-t’Serstevens, many of the expeditions of the time were only for traditional scholarship or treasure hunting (2010, p. 126). In this sense, Chavannes was not a collector but rather a protector of ancient remains. He respectedruins and preferred leaving them in place to better preserve them. In comparison with the other explorers of his time, who sought to obtain as many precious objects as possible, Chavannes preferred to bring back to France objects that were little appreciated by collectors but endowed with scientific or archaeological value, whether they were authentic or, for the most part, simple copies, having kept their original shape and colour. Chavannes can thus be considered a pioneer of Chinese archaeology. He collected more than 1,300 estampages, or stampings, of bas-reliefs and inscriptions, made about 1,700 photographs, and collected 238 popular Chinese New Year images as well as many ancient and modern Chinese art books and various objects. He collected original works of art, although in small numbers and at low prices, which were easy to acquire on the market. They are preserved today in museums, libraries, and among the family’s descendants. At the same time, his wish was above all not to call into question the conservation of these precious objects on site, at a time when there were no local measures for the heritage protection (He M., 2019, vol. 1, pp. 200, 377).

Stampings

The Chavannes collection contains stampings of two types: bas-reliefs and inscriptions. The former were collected primarily from the offering chambers of Wu Liang ci and Xiaotangshan 孝堂山, and also of Shandong and Henan. The stampings of inscriptions that Chavannes collected relate mainly to the inscriptions of Mount Taishan, the Longmen Grottoes, and the aforementioned offering chambers.

With the exception of the Taishan stampings, which were published and studied in the monograph Le T'ai chan (1910), all the others were mainly published in La Sculpture sur pierre en Chine aux temps des deux dynasties des Han (1893) and in Mission archéologique dans la Chine septentrionale (1909, 1913, 1915). The stampings were scattered between the Société Asiatique, theMusée Guimet, the Bibliothèque nationale de France, and the Musée Cernuschi, without any coherent distribution. The Musée Guimet, including its library, conserves about 630 pieces, the Société Asiatique about 610, the Department of Manuscripts of the Bibliothèque nationale de France (Richelieu Site) 71, the Institut des Hautes Études chinoises probably one, and the Musée Cernuschi 14, of whichten are kept in the reserve and four have disappeared. With the exception of those in the Cernuschi museum, all of these stampings have been cataloged and digitised under the direction of Jean-Pierre Drège, who has identified a total of approximately 1,313 pieces in the database (2002, 2004, 2005).

Photographs

Chavannes was the first to systematically photograph monuments in China for purely scientific purposes. These photographs (except the stampings), of a total of 704, were published for the most part (669) in the two volumes of plates of the Mission archéologique dans la Chine septentrionale (1909), and 35 in the monograph Le T’ai chan (1910). Chavannes was the first to make a complete series of photographs of the caves by publishing 78 photos on those of Yungang and 121 photos on those of Longmen in the two volumes of plates. In addition, he added 18 pictures of Cave Temples (Shikusi 石窟寺) in Gongxian 鞏縣 in Henan, and two images of Thousand Buddha Mountain in Jinan 濟南. In addition to photographs of Buddhist sculpture from the 5th to the 8th century AD, he published 30 images of T'ang and Song imperial burials, as well as 401 images of scenic views. The photographic collection of this mission was first kept at the bibliothèque Jacques Doucet, before being transferred to the Musée Guimet in 1918 (Ghesquière J., 2005, p. 17). Today, all the pictures of the Chavannes mission of 1907, i.e. around 1,700 glass plates, are in the reserves of the Guimet.

The Various Objects at the Musée Guimet

Chavannes donated various objects he had collected during his 1907 mission in China to the Musée Guimet. These include bronze mirrors and plaster casts, brass amulets, coins, and bits of Koguryo tiles and architectural elements, as well as terracotta grave goods of a tomb in Henan (discovered during construction work on the Bianluo 汴洛railway line, between Kaifeng and Luoyang, in July 1907). The only authentic archaeological excavation artefacts are from the tomb of the official Liu Tingxun 劉庭訓 of the Tang Dynasty (Huo H., 2017, p. 49); among these are a horse, two seated winged lions, two statuettes, two vases, three slabs, and a statue of a camel. Photos of these objects are published in Mission archéologique dans la Chine septentrionale (1909, Plates, vol. II, n° 525-537). The objects themselves are kept today in the Guimet museum’s reserves. Other objects were exhibited in the Galerie de l'Indochine of the Musée Guimet from May 27 to July 31, 1908 (De Milloué et al., 1908, p. 4). These were fragments of inscribed bricks and tiles from the tombs of the princes of Koguryo, and 28 casts of ancient Chinese metal mirrors kept in the imperial palace of Mukden, exhibited in two display cases. Today, in room 605 of the permanent exhibition on Korea at the Musée Guimet, the following objects are exhibited: an architectural element with an inscription (MG, MG 14320), a tile end cap decorated with a mask of a monster (kwimyon) (MG 14351) and a polylobe bronze mirror from the Koryo period (MG, MG 14282).

After the death of Chavannes, thanks to a donation from Alice Dor, the Musée Guimet installed a room on the first floor dedicated to him, which was inaugurated in 1921 and contained the photographs, stampings, and archaeological monuments as well as all the photos of the 1907 mission that he had brought from China. For the installation of this room, Alice had also borne part of the costs of fitting out the former room reserved for jades and the office dedicated to the photographic department (Musée Guimet, 1928, p. 12). Today, this room no longer exists; it was given to various uses during the development of the museum.

Popular Chinese New Year Images

Chavannes collected a total of 238 popular Chinese New Year images during his 1907 trip to China, to which many duplicate and triplicate copies must be added. Among these images, most bear a religious character, and 87 stampings are of theatrical or literary inspiration (Eliasberg D., 1978, p. 9). Today these images are kept at the Société Asiatique.

Carpets

Two carpets from Chinese Turkestan (Xinjiang) dated between the 16th and 17th centuries were donated by Chavannes on October 23, 1911 to the Musée Cernuschi (inv. MC 05249-MC 05250).

Chinese Drawing Books

In the Chavannes collection of works of art, there are also two Chinese drawing books from the Qing dynasty, now kept in the library of the Institut national d’histoire de l’art. These are the book Wu Yue suojian shuhua lu 吳越所見書畫錄 by Lu Shihua 陸時化(19th century) and the book Zhide zhi 至德誌 by Wu Dingke 吳鼎科 (1762).

Chavannes was also in charge of acquiring Chinese books for the art and archeology library of Jacques Doucet (1853-1929), a major fashion designer and collector, who planned to add a Chinese art library to the large collection that he had built at the beginning of the 20th century. This figure had resorted to Chavannes, who bought Chinese books in bookstores in Japan, such as the Bunkyûdô 文求堂shop in Tokyo, as well as in China, or through the missionary study center in Zikawei, or through sinologists sent on a mission organised and financed by Doucet. Thus, ona mission in 1914, Victor Segalen bought all the works indicated by Chavannes for Doucet. The list of works, identified as having been bought on the advice of Chavannes by a short notice inserted inside the books, constitutes the heart of the Chinese collection of the Doucet library belonging today to the National Institute of Art History. This collection sheds light on Chavannes' choices, linked on the one hand to his own research and, on the other, to what he considered to be essential books for sinological study. Thus it favoured epigraphy and calligraphy, followed by archeology and painting (Pirazzoli-t’Serstevens M., Laurent C., 2007, p. 109-127).

Chavannes’s personal oriental library is kept at the Société Asiatique in the Chavannes collection (Sénart E., 1918, p. 190) and part of this collection is characterised by catalogues and studies of Chinese epigraphy, such as the Jinshi suo 金石索(The Sequence of Metal and Stone Objects) and the Jinshi cuibian 金石萃編(General Collection of Metal and Stone Inscriptions).

Auction

In March 2017, an auction was organized by Millionasium concerning the collection of Doctor Pierre Thierrart (1918-2016), collector of Asian works of art. In this collection were several books by Chavannes, such as the four volumes of the A Mission archéologique, La Sculpture sur pierre en Chine, Les Six Monuments de la sculpture chinoise, and Le T’ai chan, Les Mémoires historiques de Se-ma Ts’ien. All were sold at very high prices.

Related articles

Collection / collection d'une personne

Personne / personne