ENNERY Clémence d' (EN)

Biographical Article

Clémence d'Ennery (1823-1898), founder and donor of the Musée d'Ennery, which opened in 1908, bequeathed her collection to the French State to make a "museum accessible free of charge to the public" in 1892. This donation consists of the house she had built at 59, avenue du Bois de Boulogne in Paris to exhibit her collection of Chinese, Japanese, and Korean "chimeras" represented in different materials and shapes, as well as a generous allotment for the upkeep of the museum (AN, 20144795/29, U8 d'Ennery, will of June 29, 1894). In 1897, Robert de Montesquiou Fezensac (1855-1921) described her Japanese collection as one of the "most important" of the 19th century, comparing Madame d'Ennery to collectors Michel Manzi (1849-1915), Philippe Burty (1830-1890), Charles Gillot (1853-1903), and Louis Gonse (1846-1921) (Montesquiou R., 1897, p. 1).

Joséphine Clémence (known as Clémence or "Gisette") Lecarpentier, daughter of Armand-Louis-François Le Carpentier de Saint Amand (known as Lecarpentier) and Joséphine Cousteau de la Barrère, was born in Paris on August 29, 1823. She died in the 16th arrondissement of Paris, at 59, avenue du Bois de Boulogne (present-day avenue Foch), on September 7, 1898 (AP, V4310048) and is buried in Père-Lachaise cemetery. As the Lecarpentiers came from the lower nobility, Clémence had a well-to-do upbringing: her father, a former squadron leader, was an army pensioner, Chevalier de la Légion d’honneur, annuitant, and owned several properties. The Lecarpentier family endowed her with 95,000 Francs upon her marriage to the lawyer Charles François Xavier Desgranges (1815-1880), son of the deputy mayor of the 11th arrondissement of Paris, on May 22, 1841 (AN, MC/RE/XXX/ 822). After their marriage, the Desgranges couple lived in the Lecarpentier property at 56, rue de Bondy (in the Porte Saint-Martin Theater district). The couple proceeded to a separation of body and property on May 7, 1844 when Desgranges left for Africa to pursue a career in the colonial administration. He died in Constantine (Algeria), on July 29, 1880 (ANOM, Constantine, Algeria, July 29, 1880, act 405). His absence allowed Clémence to lead an independent life quite remarkable for a woman of the time; she took advantage of investment interest and family inheritances to develop her collection and to buy properties in Paris, Antibes, and Cabourg that she owned in her own name according to a marriage contract signed in 1880 (AN, MC/ET/XXVI /1391).

In this district of the rue de Bondy, she met her second companion, the playwright Adolphe Philippe (known as "Dennery") (1811-1899), when the latter was starting out in the theatre. They are said to have met in 1841 (some speak of an affair which caused the departure of Desgranges), or shortly thereafter. In 1845, they co-wrote the comedy Noémie (Clémence adopting the pen name "Clément") and in 1847 the drama La Duchesse de Marsan (under the name of "Mme Desgranges") (Emery E., 2019, p. 205). She accompanied Adolphe in the life of the theatre, attending castings, rehearsals, and interviews. She refined the lines of their plays and was referred to as a "collaborator" in the press (Emery E., 2020, p. 26-27). Finally, although they kept separate residences in the same neighbourhood, numerous letters and descriptions of dinner parties made by the Goncourt brothers from 1858 to 1870 show that it was "Gisette" who served as hostess for Adolphe, who called her "my wife". The Goncourts trace this bohemian life in their Journal and in their novel La Faustin where Clémence serves as a model for the character of Maria, known as "Bonne Âme" (Goncourt E. de, Goncourt J. de, 1989). Her best friends were actresses and courtesans like Lia Félix (1830-1908) and Marie-Anne Detourbay (known as "Jeanne de Tourbey", future Duchess of Loynes, 1837-1908).

Most researchers describe Clémence d'Ennery, wrongly, as from the working class, a minor actress maintained by Adolphe. This misunderstanding was reinforced by her nickname "Gisette" (or Gizette, as d'Ennery writes). Clémence, however, was never an actress, which explains her absence from the theatre archives examined by Camille Despré (Despré C., 2016). Moreover, it was Clémence who would have promoted Adolphe's work, if not by exercising her charms with the ministers (as suggested by the Goncourts), at least by appealing to her contacts in the world of finance (the sister of Charles Desgranges married Achille Antonetti, of the Banque de France, in 1842) and politics; she wrote, for example, to the Minister of Public Instruction (and future President of the Republic) Raymond Poincaré (1860-1934) in 1895 to ask for the croix du commandeur of the Legion of Honour for her husband (BNF, Poincaré Papers , NAF 16000, fols. 4-5). In fact, in 1860, Adolphe Philippe obtained authorisation to call himself Adolphe d’Ennery; he was appointed officier (1859) then commandeur (1895) of the Légion d’honneur (AN, LH/2141/57, file Philippe d'Ennery).

Adolphe and Clémence (who had lived together since the 1850s) only married after the death of Charles Desgranges (July 29, 1880). The civil ceremony of May 30, 1881 took place in the house that Clémence had begun building in 1875, on land acquired, as shown in the purchase contract (MC, ET/XXVI/1351), with her own funds: this is the current site of the Musée d'Ennery. Until the death of Clémence in 1898, this house was a place of great sociability ; weekly dinners brought together friends and colleagues frequenting the world of theatre and the press. The couple was known for their hospitality, whether in Paris or in their villas in Cabourg, Antibes, and Villers-sur-mer.

The Origins of the Collection

In interviews given to the press in the 1890s, letters written to the Ministry of Fine Arts, wills, and inventory ledgers, Clémence d'Ennery repeats that she began her collection in the 1840s following an adolescent "love" for chimeras that never left her. Instead of buying dresses, the young Clémence saved money to buy small sculpted objects from the Far East in antique shops (Guinaudeau B., 1893, p. 1). This taste for Asian objects was possibly inspired (or shared) by other family members (we know that a Namban chest, for example, came from her mother, who died in 1862) (MNAAG, A. d' Ennery, inventory "6e mille", object 672, p. 68 ; Emery E., 2022).

As early as 1859, the Goncourt brothers spoke of her "collection of Chinese monsters" (Goncourt E. de, Goncourt J. de, 1989, June 12, 1859). Jules de Goncourt was dazzled by the exhibition of 150 chimeras that "Gisette" installed in her apartment at 14, rue de l'Échiquier with shelves and light specially designed to showcase them: "What a singular idea for a woman! When I was first told about it, I immediately thought that you were not a woman like [the] others” (Goncourt E. de, Goncourt J. de, 1989, December 29, 1859).

In 1861, when she changed apartments, the core of the future Musée d'Ennery was described by journalists as the fruit of more than ten years of work, a collection of 200 chimeras in jade, porcelain, bronze, and rock stone that was "complete" and "rare among all” (E.D., 1861). An exhibition of the collection at the Hotel Drouot in April 1861 preceding a planned auction elicited compliments, particularly concerning its "incomparable originality" ("Expedition in China", 1861, p. 7). The sale does not seem to have taken place; a few months later, the Goncourts spoke of the installation of a "Chinese museum" in d'Ennery's apartment above the foyer of the Théâtre Saint-Martin (Goncourt E. de, Goncourt J. de, 1989, November 21, 1861).

In 1866, probably after a fire in their apartments adjoining the Théâtre Saint-Martin (reported in a news item from Le Figaro; Claretie J., 1866, p. 7), Clémence moved in with Adolphe to a mansion he built at 4, avenue d'Eylau. The d’Ennery couple spent part of the year in Cabourg, Villers-sur-mer, Antibes and Uriage and Clémence continued to buy Asian objects for their various residences (MNAAG, A. d'Ennery, inventories "mille", s.c. ; Emery E., 2022). Their friend and collaborator Jules Verne (1828-1905) described the house in Antibes in 1873 as "a real museum" (Verne J., 1873, p. 219).

In 1875, Clémence decided to buy land in the 16th arrondissement of Paris and to have the architect Pierre-Joseph Olive (1817-1899) build the "Villa Desgranges" (the future Musée d'Ennery), with the intent to bring together the entire collection in galleries specially designed to receive them. The Ennery collection is therefore the work of Clémence alone. All of Adolphe's friends spoke, in fact, of a "mania" of Clémence that Adolphe would have "tolerated" for a long time without sharing it (Rochefort H., 1908, p. 1). Unfortunately, like most wife-collectors who accepted a marriage contract based on communal property, the name of Clémence d'Ennery was eclipsed in the 20th century by that of her husband, thus explaining the unfortunate tendency to attribute the collection to Adolphe.

Collection Contents

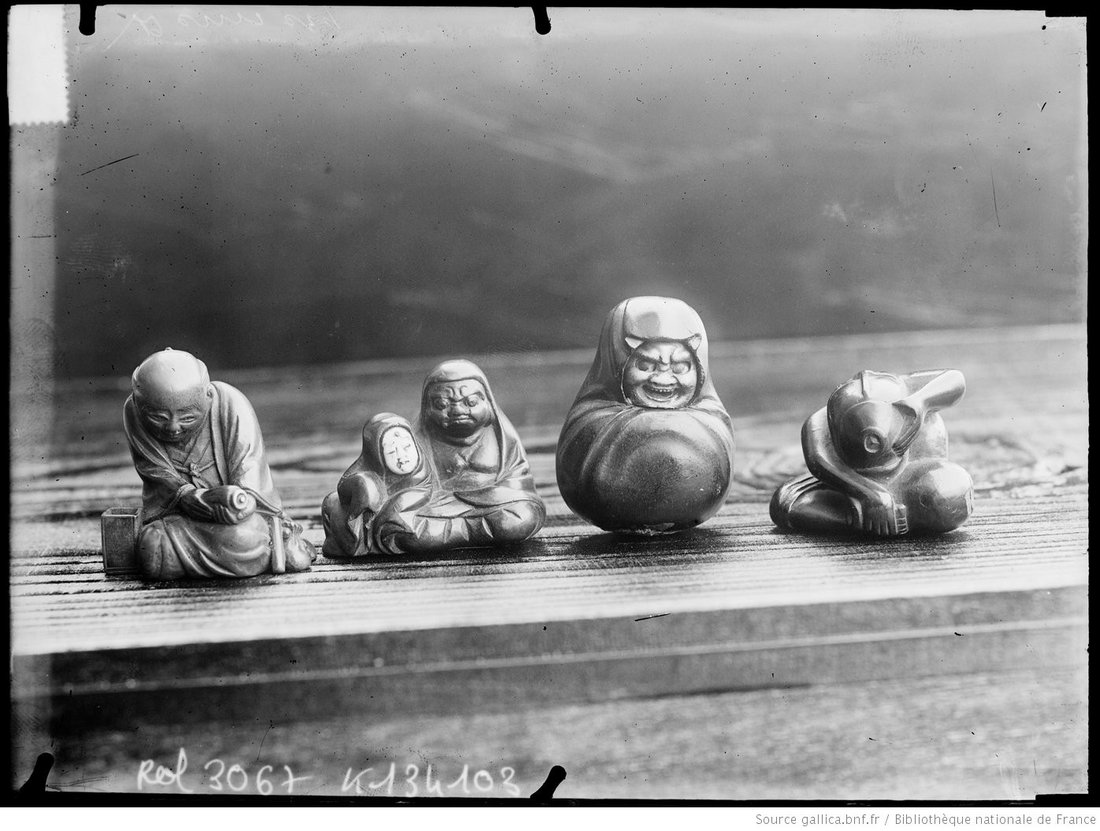

Unlike other collectors of her time, such as Ernest Grandidier (1833-1912), who favoured ceramics, Ennery had no plates and only four vases in her collection, as noted by Gaston Stiegler (1853-1931). "On the other hand," he remarks, "her house swarms in profusion with the most shimmering of the most diverse trinkets, carved wood, bronze, ivory, terracotta, mother-of-pearl, hard or soft stones, jade, onyx, rock crystal, marble, etc. In that place laughs, cries, frolics, howls, shines, and terrifies everything most bizarre, eccentric, and baroque that has been invented by the most fantastic and distorting Chinese imagination that has ever danced in the minds of men” (Stiegler G., 1895, p. 2). She was much more interested in highlighting the artistic diversity manifest in representations of "chimeras": from the material used to differing iconographic representations.

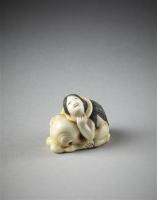

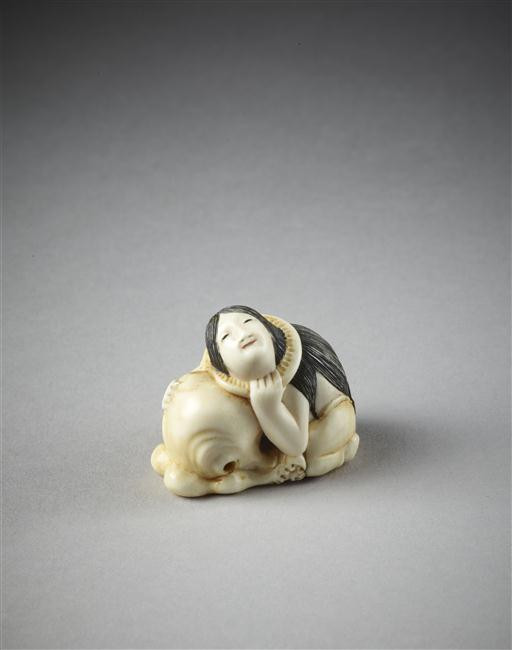

At her death, the personal inventory of Clémence d'Ennery stops in media res at 6,296 objects (MNAAG, A. d'Ennery, inventory "7e mille", n.c.). When the museum opened in 1908, Émile Deshayes, the first curator, classified objects into nine categories: 1) statuettes ("representing characters, real animals, mythical animals"); 2) netsuke; 3) dolls; 4) display cases containing various objects, including vases, goblets, incense burners, and snuffboxes; 5) “large animal statues”; 6) "inlaid, carved, gilded wooden panels"; 7) masks; 8) furniture; 9) "a collection of supports and pedestals" (Deshayes E., 1908, p. 3). A long illustrated article published by Deshayes in the journal Nature in 1898, a few months before Mme d'Ennery's death, gives an excellent idea of the seriousness given to her collection and taste by her contemporaries: while Mme d'Ennery was modest and did not want to talk about science, Deshayes stated "she knew as much about other collectors of Japanese works" (Deshayes E., 1898, p. 355).

The current collection of the Musée d'Ennery is thus doubly interesting: it represents not only a fine example of the Asian objects available on the French market in the 19th century, but also the aesthetic preferences in this field, at a time when scientific knowledge about the Japanese and Chinese art was in its infancy.

History of the Museum

It was after her second marriage in 1881 that Clémence d'Ennery began to systematically inventory her collection. From June 16, 1882, she numbered and tried to reconstruct the history of the various pieces in her collection, starting with the chimeras (MNAAG, A. d’Ennery, Carnet “No 1 Chimères”, s.c.). The many inventory logs made by Mme d'Ennery and her servants until her death, kept in the archives of the Musée d'Ennery at the Musée Guimet, not only record various elements of the collection but also provide a remarkably detailed assessment of the development of the trade in Asian objects in the 19th century. While the dates are not always precise (she records the origin of several thousand objects from memory), these notebooks make it possible to identify the type of objects purchased from close to 100 merchants (in Paris and in the provinces) and the price paid (or an estimation thereof). An analysis of these inventories was carried out by Chantal Valluy and Lucie Prost in 1975 using useful comparative tables of objects, merchants, and values. This study remains the most complete on the collection published to date, despite a few errors of date and attribution as well as misleading title: "Adolphe d'Ennery, Collectionneur" (Valluy C. and Prost L., 1975). A online transcription of these inventories (Emery E., 2022) should help facilitate future studies of the collection.

Elizabeth Emery establishes the genesis of the Ennery museum based on letters, newspaper articles and archive files (Emery E., 2020, ch. 4). As early as 1891, Clémence d'Ennery began to seek legal protection for her collection (probably after Adolphe suffered a serious illness). To this end, she sought advice from Émile Guimet (1836-1918), whose Parisian museum of Asian arts opened in 1889, and from Georges Clemenceau (1841-1929), a friend who frequented her salon and who helped Guimet carry out his project. Guimet visited the collection in June 1891 and June 1892. Pragmatically, she explained to him that the will might be contested. It is likely, as suggested by Matthieu Séguéla, that it was Clemenceau who explained to her that a donation to the State would be difficult to contest (Séguéla M., 2014, p. 56). D'Ennery appointed him executor in 1892 and bequeathed her collection to the Musée Guimet, stipulating that the objects be exhibited in a "Salle Madame d'Ennery" or "labelled gift of Madame d'Ennery" (AN, 20144795/29, U8 d' Ennery, Legs d'Ennery, codicil to the will of June 17, 1892).

The inventory of the collection then began to be carried out systematically (the numbering of objects in different notebooks and the application of the corresponding labels). In July 1892, she offered her collection to the Ministry of Fine Arts, Émile Guimet serving as intermediary between Clémence and the Minister of Fine Arts Eugène Spüller (1835-1898), whose visits in July and November 1893 were announced by the press. Spüller then asked the director of Fine Arts Henry Roujon (1853-1914) to help her reformulate the bequest. Much to Guimet's surprise, the newspapers announced that d'Ennery's collection would first be offered to the Musée du Louvre (which had just inaugurated a small section devoted to Asian arts) and only thereafter to the Musée Guimet (Emery E., 2020, ch. 4).

Due to a lack of space in the Louvre, Clémence proposed to Roujon, in June 1894, the "victorious solution" of leaving to the State not only her collection but also the residence where it was kept, with the aim of making it a "museum of national utility, accessible free of charge to the public", by adding an annuity of 16,000 francs, invested at 3% (535,000 in capital), to cover salaries and maintenance costs. This proposal for a house also offered an additional advantage: that of creating a job and housing for Émile Deshayes (1859-1916), a friend of Clemenceau who would be appointed curator of the future Musée d'Ennery (he had been hired by Guimet in 1888 who was impressed by his work at Pohl et Frères, a curio shop located at 25, rue d'Enghien in Paris). From 1892 to 1898, Clémence worked in collaboration with representatives of the ministry, with Clemenceau and Deshayes, and with his friend and supplier, the cabinetmaker Gabriel Viardot (1830-1904), to have new galleries built and fitted out (Emery E. , 2020, c. 4).

Since her marriage contract obliged Clémence to have her bequest approved by her husband, Adolphe's will of June 29, 1894 specifies, in addition, that in the event of Clémence's predecease, the objects must be presented to the public "in the organisation that they have at the time of [her] death" (AN, 20144795/29, U8 d'Ennery, Legs d'Ennery). However, it should be noted that the current Musée d'Ennery does not reflect the vision of Clémence d'Ennery alone. Between 1892 and Clémence's death in 1898, Deshayes and Clémenceau profoundly changed the collection and its presentation by buying and encouraging the purchase of a few thousand new objects and by inviting their friends to make donations to the future museum (Deshayes E., 1908, pp. 16-17; MNAAG, A du Musée d'Ennery, "mille" inventories, s.c.). Certain objects donated or purchased by Deshayes and Clemenceau (for example, masks), do not necessarily reflect the spirit of the initial collection. Furthermore, during the period from 1892 to 1898, Asian exports were designed specifically for the Western market, which diluted the first and more "rare" core of the collection made by Clémence alone (Valluy C. and Prost L., 1975, pp. 130-131, 164-168).

The museum, although largely organised at the death of Adolphe d'Ennery in 1899, did not open its doors until 1908, due to a cryptic will resulting from the sequestration of the almost nonagenarian playwright (89 years old), suffering from dementia. Adolphe had in fact never wanted to recognise his paternity of a woman who called herself his natural daughter, but the Tribunal de la Seine ended up legitimising as his heir. Her refusal to respect the terms of the will therefore further delayed the museum’s opening. Clemenceau, as testamentary executor, persisted in order for the bequest to be accepted and to persuade the heiress to provide the sums necessary for the construction of the museum (AN, F21/4469, Correspondence from the management of the Musée d'Ennery with the Ministry of Fine Arts; MNAAG, Archives du Musée d'Ennery, "Ministry" file, s.c.). The invisibility of Clémence d'Ennery as the founder of the museum (as seen above) also most likely resulted from the very strong resentment and Adolphe’s heiress felt for Clémence.

Sense of the Collection

After the deaths of the d’Ennerys, the collection was appraised first by Senator Hirayama and Guejo Masao, from the Japanese delegation, whose report was rejected by the lawyers of Adolphe d'Ennery's heiress. The latter asked (without irony) for people "whose competence in Chinese or Japanese art would be recognised" (MNAAG, A. d'Ennery, "Ministry" file, s. c., report of Dec. 11, 1902). Gaston Migeon (1861-1930), Siegfried Bing (1838-1905), and Hayashi Tadamasa (林 忠正, 1853-1906) were then chosen to check the value of the objects they had themselves sold. Mme d'Ennery had purchased neraly 500 objects from Bing and close to 100 from Hayashi (Valluy C. and Prost L., 1975, p. 152).

Today, the Musée d'Ennery is important in several respects. First, it acts as a "time capsule" documenting conservation practices at the very beginning of the 20th century. Next, it reflects the taste of a 19th century collector. It also makes it possible to study Asian objects sold on the French market from 1840 to 1898. Finally, it is rare to be able to consult such a large collection of netsukes (more than 1,000) in one place. The Musée d'Ennery archives are even more interesting because the inventories written by the hand of Clémence d'Ennery bring to light a bygone world of commerce. This is how Valluy and Prost compiled the names of merchants and identified their addresses from business directories (Valluy C. and Prost L., 1975, p. 152-159). Although often incomplete and not very scientific, Clémence d'Ennery's notes contain valuable information relating to the types of objects available on the French market, acquisition practices (by piece, by lot, broken objects, free, etc.), at the prices paid. These inventories, now available online (Emery E., 2022) therefore constitute a remarkable resource for anyone seeking to draw a geography of the Parisian trade in Asian objects from the second half of the 19th century.

Perhaps even more interestingly, this collection helps us understand the vision of a woman who sought to educate the general public – those who attended her husband's plays – and engage them in Asian arts in a free and familiar space where they would not need to read catalogues to understand the beauty and interest of the small objects on display (Emery E., 2020, chapter 4). In fact, witnesses of her time always insisted on her desire (very avant-garde) to create an alternative place to the "cold" "scientific" rooms of the Louvre and Cernuschi museums at that time.

Related articles

Personne / personne

Collection / collection d'une personne