RIVIÈRE Henri (EN)

Biographical article

Henri Rivière was born on 11 March 1864 in Paris (2, Rue Brongniart) (AP (Paris archives), civil registry deeds). He was the son of Prosper Rivière (1830–1873), a lace dealer operating from 135, Rue de Montmartre, and Henriette Leroux (1840–1912), without a profession. His brother, Jules (1865–1912), was born fifteen months later. After a sojourn at Ax-les-Thermes with the paternal family in order to flee the events of 1870–71, the young Henri, whose father died in 1873, continued his education in a boarding school in Asnières, then in the Collège Rollin (present)-day Jacques-Decour), a period during which he discovered drawing through copying the illustrations of Gustave Doré (1832–1883) and Daniel Vierge (1851–1904), and thanks to articles about exhibitions in the journal La Vie Moderne, on the Boulevard des Italiens. Turning away from the commercial career his mother had planned for him, he was trained for a while in the studio of the academic painter Émile Bin (1825–1897). In 1881, the creation of the Cabaret du Chat Noir by Rodolphe Salis (1851–1897), which he frequented assiduously from the age of eighteen onwards, introduced him to the milieu of the bohemian world of Montmartre and opened the way for an artistic career. He participated in the establishment of the eponymous journal, intermittently holding—alongside the Editor-in-Chief, Émile Goudeau (1849–1906)—the post of editorial secretary and occasionally penning articles or making drawings. At the same time, he explored the possibilities of etching, which he practised as a painter and engraver, like Félix Buhot (1847–1898), oscillating between Impressionist landscapes and fantastical scenes.

But, his name is primarily associated with the creation of the Chat Noir’s shadow theatre and a novel theatrical aesthetic. In 1886, Salis entrusted him with its artistic and technical management. He created, in particular, La Tentation de Saint-Antoine, an enchanting show (1887), La Marche à l’étoile, a mystery in ten pictures (1890), L’Enfant prodigue (1894), and Clairs de lune, a show in six pictures (1896), whose performance took place just before the permanent closure of the Chat Noir in 1897. A final show, Le Juif errant, was performed in 1898 in the Théâtre Antoine. The popular success of Rivière’s works was complemented by the publication of books that transcribed texts and scores and reproduced the successive pictures of his shows in colour lithographs.

In 1888, Henri Rivière met Estelle Eugénie Ley (1864–1943), whom he married on 14 November 1895 (AP (Paris archives), civil registry deeds). They moved to 29 Boulevard de Clichy and spent the summer in Brittany (in Saint-Briac, then in the region of Paimpol and Tréboul). In 1895, they acquired land at Loguivy, on the cliff that overlooked the mouth of the Trieux, and had a house built there, called ‘Landiris’, in which they stayed every summer until it was sold in 1913.

Inspired by the dual influence of Japanese prints and Brittany landscapes, Henri Rivière began practising wood engraving at the beginning of the 1890s. He managed to learn the technique of Japanese engraving and carried out all the stages himself, from grinding the pigments in water to the manual printing stage. Most of the wood engraving work was contained in two series, each of which was printed in twenty copies; La Mer, études de vagues (1890–1892) and Paysages bretons (1890–1894), which he presented in the exhibitions held by the Peintres-Graveurs (Painters and engravers) between 1890 and 1893.

Having witnessed the construction of the Eiffel Tower, which he photographed when he visited the site, Henri Rivière created lithographs of the Trente-six vues de la Tour Eiffel as a tribute to Hokusai’s Trente-Six Vues du Mont Fuji. His initial idea, as attested by two plates, was an album of wood engravings. He substituted this difficult technique, which was difficult to reproduce, with lithography. The thirty-six plates were presented together, in 1902, in a book published in 500 copies.

Shifting from the book format, the lithographer took a decisive step when he undertook—in conjunction with the printer Eugène Verneau—the creation of ’decorative colour prints’ intended to adorn private and public interiors, in particular school classrooms. The limited nature of the wood engraving prints was replaced by the wider diffusion enabled by the lithographic techniques. Chromatic experiments were always very important to Rivière, who sought to reproduce the graduations of his wood engravings through lithography. The Aspects de la nature (1897–1899), a suite of sixteen large-format lithographs, printed in 1,000 copies, echoed the criteria of education through beautiful images. In 1900, the series of eight large-format lithographs entitled Landscapes parisiens provided a monumental pendant to the Trente-six vues de la Tour Eiffel. With La Féerie des heures (1901–1902), sixteen lithographs printed in 2,000 copies, Rivière tackled one of his favourite subjects: the atmospheric and meteorological changes at various times of the day and in different seasons. The plates from the series of the Beau pays de Bretagne were published between 1898 and 1917, while his last series, Au vent de Noroît, was never completed.

Discovered in 1882 and abandoned in 1888, etchings reappeared in Rivière’s oeuvre in 1906 and were used until 1916. Mostly engraved on zinc, the etchings from this second period (Breton landscapes based on drawings executed outdoors) were of a different facture than the first, which combined clearly etched large-format works with the lighter lines of a soft varnish.

In the autumn of 1913, Henri Rivière went to Italy on the invitation of his painter friends, Berthe (1886–1971) and André Noufflard (1885–1968), who owned a villa near Florence. In 1916, he ended his engraving and lithographic career to devote himself solely to watercolour painting, a technique he had been practising since 1890, at first to create models for his prints and then as works in their own right. Greatly inspired by Brittany until 1916, the year he stayed there for last time, these watercolours were also executed in other regions of France, during various sojourns: Provence, where he went regularly between 1923 and 1944, the Pyrenees, Savoie, the Auvergne, Normandy, where his friends, the Noufflards, accommodated him in their houses at Fresnay-le-Long, in the Périgord, and in the Île-de-France. Shortly after the death of his wife on 24 May 1943, he painted his last watercolour at Buis-les-Baronnies, in the Drôme, where he had sought refuge in 1939. In November 1944, the onset of a sudden eye infection, which made him virtually blind, forced him to give up his art. After dictating his memoires, entitled Les Détours du chemin, he died, at the age of eighty-seven, on 24 March 1951, at Sucy-en-Brie (AD 94, civil registry deeds), in the home of Henriette Noufflard (1915-2003), the daughter of André and Berthe, his longstanding friends. He was buried in Fresnay-le-Long (Seine-Maritime) next to his friends’ property.

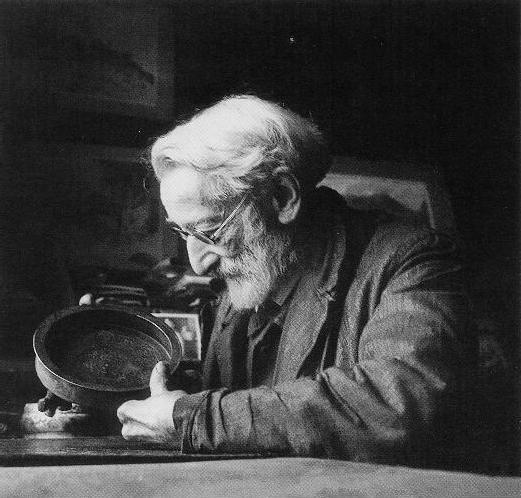

The compilation of Henri Rivière’s collection

The conditions in which Henri Rivière compiled his collection of Japanese prints are known thanks to his memoirs, Les Détours du chemin (quinoxe, 2004), in which he described how he met the three dealers who introduced him to Nippon art. At the end of the 1890s, Odon Guéneau de Mussy (1849–1931), a connoisseur of Japanese art, introduced him to the famous dealer Siegfried Bing (1838–1905), whose shop, L’Art Nouveau, was located on the Rue de Provence. Here he discovered, in the company of George Auriol (1863–1938), a friend from the Chat Noir, pottery items, bronzes, sword guards, fabrics, and, above all, prints that he found more attractive than anything else. Guéneau de Mussy took him to meet Florine Langweil and Hayashi Tadamasa. The shop run by Florine Langweil (1861–1958), specialising in the direct importation of ancient objets d’art from China and Japan, was located at the time at 4, Boulevard des Italiens; she subsequently lived in a house at 26, Place Saint-Georges (Rivière, H., 2004, pp. 87–94). Madame Langweil played a significant role in educating Rivière about Japanese art as well as in his personal life, through their friendship and his friendship with her daughter Berthe and her husband André Noufflard, both painters. Rivière spent many hours ‘rummaging through the drawers, unrolling kakemonos, caressing with eye and hand lacquered and pottery objects, and leafing through prints and books’ (Rivière, H., p. 84), and began to purchase objects and prints. Nothing is known of the number or nature of the purchases he made at Mme Langweil’s (only six prints in his collection bear the stamp of the Maison Langweil, which does not exclude the fact that there may have been others).

Rivière owed most of his collection to a competitor located at 65, Rue de la Victoire, Hayashi Tadamasa (1853–1906), whom he probably met circa 1900, at the point when the latter was organising the Japanese pavilion at the Exposition Universelle (Rivière, H., 2044, p. 95). Given Rivière’s limited funds, the richness of his collection is extraordinary: it owed much to his friendship with Hayashi. In 1902, the Japanese dealer commissioned mural paintings from him to decorate the dining room of a house built for him in Tokyo. To remunerate him for this he suggested that he select items from his personal collection: prints, illustrated books, lacquer objects, and items of pottery. Although they were brought to Japan in 1906, Rivière’s canvases were never installed, as Hayashi had passed away that year (Rivière, H., 2004, p. 96).

The characteristics of Henri Rivière’s collection

While part of Rivière’s Japanese collection was sold at auction shortly after his death in 1953 (sale at the Hôtel Drouot, Paris, 26–28 October 1953), the largest part was kept by Henriette and Geneviève Noufflard, the daughters of his friends Berthe and André Noufflard; it was then acquired by dation by the Bibliothèque Nationale de France’s Département des Estampes et de la Photographie, in 2007, at the same time as all of the contents of the artist’s studio. This collection, quantitatively exceptional due to the number and quality of its prints, without equivalence amongst the artist collectors of his times, comprised 800 objects, including 749 prints, forty-nine illustrated books, and two stencils. The chronological limits of the collection (between 1765 and 1865), correspond to the golden century of Japanese prints, that is to say the second half of the Edo epoch (1603–1868). These were wood engravings that came from the Ukiyo-e School. From this School, Rivière’s collection mostly consisted of landscapes (550 articles). In order of importance, the other genres represented were female beauty (93 articles), actors (30), and flowers and birds (27). As for the artists, two names stand out: that of Utagawa Hiroshige (1797–1858), whose works make up almost two thirds of the collection, consisting of 450 articles, and that of Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849), represented by 130 articles. Alongside thee engravings of the two artists, who were for Rivière a source of recurrent inspiration, featured the works of Kitagawa Utamaro (1753–1806) represented by thirty-seven objects , Suzuki Harunobu (1725–1770) with thirteen articles, and Ikeda Eisen (1790–1848), Utagawa Toyokuni III (12), Koryusai (9), Shunsho (6), and Kiyonaga (4), whose prints, selected with discernment, attest to his desire to avoid limiting his collection solely to objects relevant to his own artistic work, and extend it to other representatives of the art of the ukiyo-e (‘Floating world’).

With regard to Hokusai, Rivière owned the eight sheets of the Tour des chutes d’eau des différentes provinces, the three sheets of Setsugekka (Snow, moon, and flowers), forty sheets of the Cinquante-trois relais du Tōkaidō,and, above all, the entire series of the Trente-six vues du Mont Fuji, including twenty-five from the first edition with blue contours.

The prints in Rivière’s collection were, for the most part, glued around the edges on strong cardboard wider than the print, so that they could be grouped into series with made-to-measure pieces of paperboard covered with a paper created by George Auriol and with a leather back adorned with the series titles in gilt letters.

Rivière’s collection of Far-Eastern art was not limited to Japanese prints. Many objects such as paravents, lacquered objects, inrō (box-like seal holders attached to a cloth sash), writing desks, and ceramics from various eras also featured in his collection, some of which were added via bequest to the Musée Guimet in 1952. Other objects in his collection were bequeathed to the Musée des Arts Décoratifs (bequest registered in 1954), including a significant collection of Chinese clasps dating from the period of the ‘Fighting Kingdoms’, the imperial Qin and Han Dynasties.

As a complement to his artistic activities, Rivière was involved in an editorial activity that enabled him to diffuse the knowledge he acquired as he compiled his collection. Between 1913 and 1925, of the five editorial projects he was working on, one concerned Far-Eastern ceramics (Rivière, H., 1923), and another the collection of Chinese art owned by his friend Osvald Sirèn, curator at the National Museum in Stockholm (Rivière, H., 1925). As attested by a previously unseen typescript (BNF, Estampes et Photographies), a project to publish his collection of Chinese clasps did not materialise. For these publications, Rivière relied on an international network of private collectors and institutions. The quality of the reproductions of the works, which he was particularly careful about, means that these works can be used for research purposes. It is a shame that despite Rivière’s talents as an art publisher he did not publish the masterpieces from his Japanese collection.

Related articles

Collection / collection d'une personne

Personne / personne