LEROI-GOURHAN André (EN)

Biographical article

Biographical commentary

André Leroi-Gourhan (1911-1986) was a French ethnologist and prehistorian. His work was based on archaeology, ethnology, technology and art history with the same goal: to study man, from the prehistoric period to the present day. To grasp all the aspects of a given human group, he relied on diffusionist then structuralist views and questioned the material production from three types of testimonies: archaeological remains, tools and craft techniques, popular and religious arts.

From the age of sixteen, Leroi-Gourhan hunted around in Parisian flea markets and built up a collection of curiosities that he documented in his notebooks. This early collection, which included “objects in metal (African weights and edged weapons) or of bone and ivory (Eskimo), stone and ceramics (Asia and the Americas), but also human and animal skulls” (Soulier P., 2018, p. 24), was testament to his interest in tools and remains that would be at the heart of his work in the following years.

A multidisciplinary education (1927-1936)

Between 1927 and 1936, Leroi-Gourhan passionately studied several disciplines of the humanities and natural sciences: anthropology, ethnology, comparative technology, religious sciences, art history, museology. To accomplish this, he took courses at various establishments such as the École d’Anthropologie de Paris, the École Nationale des Langues Orientales, the École Pratique des Hautes Études, the Collège de France and the Sorbonne. He met his mentors during these formative years: Paul Boyer (1864-1949), Marcel Mauss (1872-1950) and Marcel Granet (1884-1940). Being interested in the Slavic and Eastern worlds, he studied Chinese as well as Russian and took part in the activities of the Guimet and Cernuschi museums. He also volunteered at the Musée d'Ethnographie du Trocadéro, where he rubbed shoulders with Georges Henri Rivière (1897-1985), who introduced him to museography, and the director Paul Rivet (1876-1958), who allowed him to spend the winter of 1933-1934 in London in order to study the collections of the British museums. (Soulier P., 2018)

Some time later, Rivet invited him to contribute to the seventh volume of the Encyclopédie française entitled L'espèce humaine. Peuples et races (1936). Leroi-Gourhan was the author of the chapter L’Homme et la Nature, in which he layed the first milestones of what would become a method of studying techniques. In this work, he also wrote the notes on the native peoples of Europe, the North Pole, the Levant, the Indies and the Far East. (Comité de l’encyclopédie française, 1936).

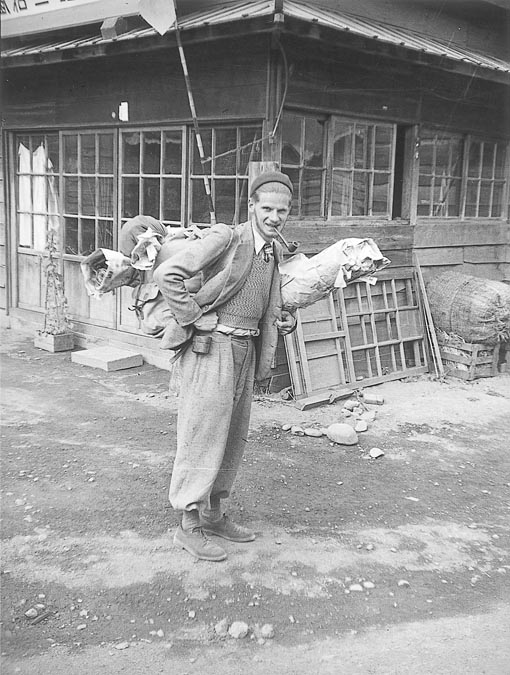

The “Mission Leroi-Gourhan” in Japan (1937-1939)

In 1937 Leroi-Gourhan was one of the first French people to benefit from a mobility grant offered by the Japanese government who was concerned about its political and cultural influence. During this two-year field experience from April 1937 to March 1939, he conducted an anthropological study of Japanese civilization and, commissioned by the Musée de l'Homme (MNHN, 2 AM 1 K59d ), he enriched the French public collections. He was welcomed by the Franco-Japanese Institute of Kansai, which provided him with accommodation on the hills of Kyoto and offered him a position as a literature professor. For two years, Leroi-Gourhan taught courses in Latin, historical grammar, modern literature, history of French literature and French civilization (MSHM, ALG17).

Even though he studied Far-Eastern art, André Leroi-Gourhan was not a specialist of Japan. To immerse himself in the visual culture of the Archipelago upon his arrival, he assiduously consulted collections of prints and illustrated works in libraries (MSHM, 137/138). He also studied Japanese archaeology, which seems to have been essential in his understanding of the way the Japanese civilization was built, from an ethnic and cultural point of view. In June 1937, he joined the team of Yawata Ichiro (八幡一郎, 1902-1987) and Akabori Eizō (赤堀英三, 1898-1986), both archaeologists at the Tokyo Institute of Anthropology, to participate in archaeological excavations at the Kamikaizuka site, in Chiba Prefecture (MNHN, 2 AM 1 K59d).

During his mission, he acquired many Japanese and English books dealing with Japanese civilization, which became part of the library of the École Française d’Extrême-Orient in 2018 (EFEO, FR EFEO A ALG). He also collected a large amount of documentation on Japan, presented in the form of files and kept since 2019 in the archives of the Maison des Sciences de l'Homme Mondes (MSHM, ALG137). These files consisted of observation notes and drawings, reproductions of objects and decorations, or bibliographic references. Their study highlights the recurrent use of the Manga by Katsushika Hokusai (葛飾北斎, 1760-1849), which gives pride of place to drawings of daily life or craftsmen at work. This is why Leroi-Gourhan saw in Hokusai the “Father of Japanese Ethnography” (Leroi-Gourhan A., 2004, p. 22). In search of Japanese authenticity, André Leroi-Gourhan sought to acquire a Japanese “eye”, immersing himself in illustrated books that depicted folk arts. This iconographic study also allowed him to identify the objects to collect.

In his correspondence (Leroi-Gourhan, A., 2004), Leroi-Gourhan explained how he wanted to describe a Japanese society free of Western influence. However he noticed during his stay, at the beginning of the Shōwa era (1926-1989), that material environment was altered by Western culture. Japan's industrialization policy, which was the focus of successive governments from the end of the shogunal regime in 1868, appeared to him as an obstacle to the study of traditional Japanese culture. This point of view is reminiscent of that defended by anthropologists such as Paul Rivet (1876-1958) and Franz Boas (1858-1942), who encouraged documenting everything cultural that was threatened by modernization through their practice of “salvage ethnography”.

Following the teachings of the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro and of Marcel Mauss (Mauss M., 2002), Leroi-Gourhan primarily collected everyday objects and handicrafts. He believed that “[folk art] is essential on a daily level: what is lived every day and by every man, in every country, is not signed, and what makes a great French, Italian or Chinese masterpiece comes from these millions of anonymous trinkets constituting the daily resources of the people” (Leroi-Gourhan A., 2004, p. 286). Folk arts are considered to be distinct from fine arts, which cater to a restricted and cultured elite. The consideration Leroi-Gourhan accorded to the arts and customs of the working classes is in line with the concerns of his time: since the middle of the 19th century in Europe, various artistic and political currents arose in reaction to the development of industry, which threatened the survival of craftsmanship, but also to defend the assertion of national and regional identities. In Japan, he discovered the “Folk Craft Movement” Mingei (民芸運動), which promoted traditional Japanese craftsmanship and whose creation was inspired by the Arts and Crafts movement from England. Leroi-Gourhan visited the Japan Folk Crafts Museum (日本民藝館, Nihon mingeikan) in Tokyo, yet qualified the Mingei as a “movement of peasant art snobbery” (Leroi-Gourhan A., 2004, p. 40). He also discovered Japanese folkloristics (民族学, minzokugaku) as well as the Attic Museum, which was both a museum and an ethnological society interested in Japanese material culture. Leroi-Gourhan acquired thirteen bulletins from the Attic Museum, published between 1934 and 1938, which allowed him to learn about the state of research in Japan. He was particularly interested in ethnographic surveys carried out in rural areas as well as “Interviews on Folk Utensils” (1937) and “Instructions for the Collectors of Folk Utensils” (1936), published in Japanese with illustrations.

Leroi-Gourhan worked between 1937 and 1939 on an important research paper on Japanese ethnography, Vie esthétique et sociale du Japon nouveau (Aesthetic and Social Life of Modern Japan). However, the study of folkloric objects and customs led him, around 1938, to embark on the writing of another paper, Formes populaires de l’art religieux au Japon (Popular Forms of Religious Art in Japan), which remained unfinished and will only be published posthumously Pages oubliées sur le Japon (Forgotten Pages about Japan) in 2004. In this collection, he wanted to understand Japanese folklore from the cataloging and study of patterns he had observed in popular and religious arts.

Return to France and subsequent work (1939-1986)

Back in France, he continued the various works he had begun throughout his stay and worked on an exhibition project relating to Japanese civilization. He wrote several chapters of Formes populaires de l’art religieux au Japon, the publication of which was announced by the publisher, Éditions d'Art et d'Histoire, in 1943 (Leroi-Gourhan A., 1943). Several institutional, political and methodological factors ultimately led him to abandon it. Although Leroi-Gourhan did not publish any book dealing specifically with Japanese culture, his activities of collecting tools and observing techniques would contribute to a general paper on comparative technology, entitled Evolution et Techniques (1943-1945), and also his doctoral thesis Archéologie du Pacifique Nord, which he presented in 1944. In the years that followed and throughout his teaching and research activities, Leroi-Gourhan specialized in prehistoric ethnology. He was appointed Chair of Colonial Ethnology in Lyon (1944) then to that of General Ethnology at the Sorbonne (1956) and finally, in 1969, Chair of Prehistory of the Collège de France, formerly held by the Abbot Breuil (1877-1961). (Soulier P., 2018)

His best-known work is Gesture and Speech (1964-1965). Published in two volumes, it begins with the origins of humanity, extends to modern periods, and discusses somewhat alarming prospects for the future. Leroi-Gourhan presented a global anthropological study of all his explored disciplines: anatomy, archaeology, technology, linguistics, mythology, art history, sociology or science.

André Leroi-Gourhan's work includes some 20 books in French on technology, ethnology and prehistory. These include L'homme et la Matière (1943), Milieu et Techniques (1945), Ethnologie de l'Union Française (1953), Les religions de la préhistoire (1964), The Dawn of European Art: An Introduction to Palaeolithic Cave Painting (1992), and Treasures of Prehistoric Art (1995). Some have been translated into ten languages. Added to these works are several hundred articles, numerous prefaces, contributions to collective publications, fascicles and compilations of the courses taught during his years as a professor (Bulletin de la Société Préhistorique Française, 1987). These important works illustrate mankind from the diversity of its material production in order to define universal concepts. Thus, we can grasp the character of Leroi-Gourhan as a collector of objects, patterns and experiences. Only a myriad of examples along with their comparison, throughout time and space, satisfied his quest aimed to qualify the essence of man through the study of material culture.

© archives MSHM / fonds Leroi-Gourhan

The collection

André Leroi-Gourhan's collection consists of approximately 2,500 objects sourced during his mission to Japan between 1937 and 1939. (MQB, Dossiers de collection)

Throughout his stay, he wrote notes following the standards established by the Musée de l'Homme. These notes, recorded in small notebooks (MQB, D001863/38710; MH, DT67-6), allowed him to establish "ten-point sheets" which provided lots of details for each object: vernacular name, date, place of collection, use, materials and dimensions, etc. The information recorded in the computer database of the Musée du quai Branly comes mainly from these files, which were given to the Museum along with the objects and a collection of 400 photographs. However, these represent only a small proportion of the photos and postcards that André Leroi-Gourhan collected in Japan. Professor Yamanaka Ichiro (山中一郎, 1945-2013) presents them in full in his collection Le Japon vu par André Leroi-Gourhan: 1937-1939 (2000-2007).

Prehistory

During the excavations carried out in the summer of 1937 in collaboration with researchers from the Imperial University of Tokyo, Leroi-Gourhan was given around 220 remains exhumed on site. Subsequently, on certain occasions, he was able to obtain around 60 additional archaeological objects. In total he gathered nearly 280 specimens which consist, for the most part, of prehistoric or protohistoric pottery shards. Some fragments also show the famous string pattern characteristic of terracotta production from the Jōmon period. Also found in this collection are shells, animal and human bones, and a few heads of weapons and tools.

Technology

A good part of the collection is about techniques. These include the acquisition modalities of raw materials, such as gathering or breeding, manufacturing methods (transformation of these raw materials into tools, objects, food) and product consumption methods, i.e. say their use. The objects collected date mainly from the 20th century and were chosen as common ones found in most Japanese homes at the time. However, testimonies related to modern or industrial techniques are excluded from the collection, even those having been manufactured on the Archipelago. According to André Leroi-Gourhan, this type of object did not belong to Japanese culture insofar as the production method was imported from the West less than a century ago (Leroi-Gourhan A., 2004). On the other hand, more than 90 objects were antiquated or qualified by the collector as "out of use" (MQB, inv. D001863/38710). They either had become obsolete as the activities for which they were used were disappearing or gradually replaced by newer versions. They sometimes are dated to the Taishō era (1912-1926) or Meiji (1868-1912), or even to the Edo period (1603-1868).

The collection contains objects relating to rural life such as clothing accessories used for working the fields, harnessing oxen and horses, fishing or hunting. Leroi-Gourhan specifies that the hunter's equipment gradually goes out of use as the profession dies out. A set of around 20 objects relate more broadly to armaments and more than half date from the Edo period. However, there is no saber hilt or element of samurai armor, which so appealed to Western collectors, but rather more modest accessories such as chain mail or quivers.

Leroi-Gourhan also acquired several tools and products related to crafts such as joinery-carpentry and basketry. About 50 objects relate to work with paper or textile fibers. In particular, there were seven samples of silks dating from the Edo period as well as fourteen wooden printing boards. The latter were used for printing on paper or fabric, but Leroi-Gourhan indicates that their use was disappearing in favor of plates made of zinc. Most of them display auspicious motifs including Daruma, Hotei and other deities from the Shinto-Buddhist syncretism; the treasure ship of the seven gods of good fortune; pearls; jewels; stylized animals and plants. Some of these printing plates were used for a more utilitarian production such as an account book, a medicine leaflet and a children's game.

A set of five objects illustrates the stages for the production of a figurine in the form of a "female Daruma". It consists of the used mold as well as four molding samples. The first figurine is in raw clay, as it appears when it comes out of the mold, a second in raw clay having been touched up before firing, the third one after firing and a fourth figurine in its final appearance, after applying the paint. Leroi-Gourhan details all the gestures made by the craftsman, for the molding and unmolding of these figurines, in his notebooks sent to the Musée de l'Homme.

More than 100 objects relate to everyday life. There are approximately 50 pieces of clothing and 30 toiletries including a large dressing table with drawers equipped with a mirror and make-up utensils, furniture, objects for decoration or housekeeping, games and toys, fans and several items related to trade, tobacco consumption and gifts. About ten objects relate to writing and calligraphy, including a brush in its case from the Edo period and two inkstands. The first is the model most commonly used at the time while the second corresponds to its older less used counterpart. Finally, the collection includes more than 150 objects relating to food, an area that interested Leroi-Gourhan and for which he produced a large number of notes and drawings (MSHM, ALG137/1/10). There are dishes and many kitchen utensils, as well as foodstuffs. Within this set is a group of around 60 specimens that relate to the consumption of tea.

André Leroi-Gourhan approached techniques as a subject of study in itself in his work on comparative technology, Evolution and techniques (1943-45). However, his worksheets and their classification, in the form of thematic tabs, show that he saw the study of techniques in Japan from a more global perspective by linking them to folklore. He thus establishes transversal links between certain objects and the motifs present in popular and religious art. On a sheet attached to Japanese objects and iconography, classified in a tab entitled "Techniques" (MSHM, ALG137/1/4), he associates, for example, the straw coat (of which there are two examples in the collection) to the deity Daikoku, the centipede and the plow.

Social and religious life

The major part of the collection focuses on social and religious life, and the objects relate to calendar festivals and popular arts. During his stay, Leroi-Gourhan approached antique dealers but he also visited many temples and sanctuaries to attend rituals (Leroi-Gourhan A., 2004). These steps allowed him to acquire some objects related to the life of the temple such as clothing and accessories worn by priests, objects of divination, talismans and ex-votos. He also collected clothing, masks and musical instruments (bells, clappers, drums, flutes, biwa) associated with sacred dances and plays performed within religious buildings.

The collection includes nearly 160 objects related to the different festivals of the religious calendar such as the New Year celebration, the feast of the dead (obon) or the setsubun feast for the expulsion of demons and calamities. The most complete lots are for the tango no sekku boy celebration and the hina matsuri doll celebration. One finds in the collection an imposing palace of dolls, exhibited in one’s house during the festival dedicated to young girls. The set consists of a scale model of a palace, 15 dolls with the effigy of an imperial court as well as five decorative elements (71.1939.97.477-497). Similarly, he collected objects Japanese families used to decorate their homes for the birthday of young sons: miniature armor represented with a bow, arrows and a saber on stands (71.1939.97.502-514), as well as a fabric carp that was hung on an outdoor pole or koinobori (71.1939.97.394-403), since it was the symbol for boys. For these two festivals celebrating children, Leroi-Gourhan also collected the offerings that are placed with the stated palace or armor. They are actually miniature objects made of paper, fabric or wood, that represent sake flasks, bouquets in vases and cakes (71.1939.97.498-501). The real cakes eaten during these festivities are also present in the collection.

Leroi-Gourhan also collected around 340 folkloric objects: several dozen ema, including three dating from the Edo period and 10 of the 12 animals of the Far Eastern zodiac, four ancient Ōtsu-e (or reproduction) and 120 omocha . This joins trinkets and toys, but also local specialties and travel souvenirs. We also find in the collection some whistles, toys, kites and 50 figurines bearing the effigy of various deities (Daikoku, Ebisu, Benzaiten, Tenjin, Daruma) or animals associated with the gods and good fortune (fox, rabbit, magpie, rooster, crane, tortoise, owl, wild boar, ox…). Finally, a collection of almost 900 religious images (ofuda) shows the many sheets collected by the faithful during pilgrimages, in particular that of the 33 temples of Kansai, as well as the illustrated talismans that are placed on the home altar or in the house.

The Japanese government as a patron?

Leroi-Gourhan collected two-thirds of the objects himself making up the collection that bears his name at the Musée de l’Homme. Around 500 specimens were selected by the Kokusai Bunka Shinkōkai (KBS, 国際文化興会) (MQB, inv. 71.1947.51). This “Center for International Cultural Relations”, which worked to promote the economic and political influence of Japan through tourism and the promotion of Japanese culture, is at the origin of the scholarship from which Leroi-Gourhan benefited (Leheny D., 2000 , Shibasaki A., 2014). The Musée de l'Homme had seized this opportunity to entrust the latter with a mission to collect ethnographic material, but had only allocated a modest budget. The purchasing budget therefore came mainly from the KBS, which wanted part of the Leroi-Gourhan collection to be a gift from Japan to France (MNHN, 2 AM 1 K59d).

Although the organization gave carte blanche to the collector in his choice of acquisitions, the stakes of this collection and its visibility was cultural as well as diplomatic for the Japanese government. Since the end of the 19th century and the Universal Exhibitions, Japan has above all wished to offer the West the highest expression of its culture and craftsmanship. The KBS proposed to finance an exhibition in Paris, composed of its vast selection of objects and photographs that showcased the decorative arts and their production. Leroi-Gourhan had ensured that the Museum kept a complete list of the elements provided by the KBS (MQB, collection files, D005326/51874) in order to guarantee his own neutrality with regard to this part of the collection. He suspected there may have been a somewhat propagandistic purpose for the exhibition (Leroi-Gourhan A., 2004, p. 84).

He indicated that he personally chose only 23 objects from what the Japanese government offered, in particular some kitchen utensils from rural areas. Indeed, Leroi-Gourhan observed at the beginning of his stay that "the Japanese peasant is unknown here and [that he himself] already has here, among the officials, the reputation of the phenomenon that descends into the rice field" (Leroi-Gourhan A., 2004, p. 48). The “two collections” in the collection highlight the differences between the vision of an ethnologist, who values the everyday and the ordinary, and that of Japanese officials, who intend to illustrate their culture through activities deemed more noble or refined.

Within the objects chosen by the Kokusai Bunka Shinkōkai, there are several sets linked to the excellence of Japanese craftsmanship: carpentry, basketwork, weaving of brocade fabrics, papermaking and printing, making umbrellas and fans, making cast iron teapots, production of lacquer and lacquered objects. The collection includes specimens ranging from untreated raw materials to finished products, as well as the tools used for production. Photographs enrich the documentation on these skills, with the help of images of craftsmen at work or of objects arranged according to the stages of their manufacture. Japanese aesthetics and etiquette are illustrated by a large selection of objects relating to flower arrangement, decoration, furniture or the tea ceremony. To represent spiritual life, the KBS included in its selection a bow with arrows and quiver, used for ritual ceremonies, as well as all objects that make up a domestic altar or kamidana (71.1947.51.212-224 and 71.1947.51.351-354).

The collection in France (1939-1998)

Initially entered into the collections of the Musée de l'Homme in several successive installments, the objects currently are kept at the Musée du Quai Branly under the following inventory numbers: 71.1939.97 (667 objects); 71.1939.99 (23 objects); D 71.1947.14 (47 items); 71.1947.51 (519 items); 71.1950.43 (134 items); 71.1953.94 (34 items). Only the archaeological collection remains today at the Musée de l'Homme, under the collection number 39.98 (281 objects).

The first installments were made in 1939 and bear the mention “Mission Leroi-Gourhan”. They bring together archaeological remains and almost 700 ethnographic objects. These include tools and samples for papermaking, basketry, textiles and woodworking, kitchen utensils and foodstuffs, clothing, weapons, household objects and leisure objects linked to rural life, objects linked to rituals and calendar festivals, popular and folk art objects and musical instruments.

In 1947, Leroi-Gourhan entrusted the Museum with a donation of 47 objects relating mainly to the graphic arts. This set includes an ema, fifteen religious images, three Ōtsu-e, two textile prints, a rack and a lacquered meal tray. A second installment also was made in 1947 and included objects chosen by the Kokusai Bunka Shinkōkai, which the Musée de l'Homme probably was unable to accept during the war.

Leroi-Gourhan had considered, towards the end of his mission, how to present his collection. In particular, he envisaged a temporary exhibition centered on Japanese popular arts for the Guimet Museum (Leroi-Gourhan A., 2004). This finally was held in 1947 at the Musée de l'Homme and included 43 objects collected by Leroi-Gourhan, as well as 18 objects from the KBS donation recently acquired by the Museum. Archive photographs show that approximately 110 objects from the collection gradually were placed on permanent display at the Musée de l'Homme, in showcases devoted to Asia. They remained there until the beginning of the 1980s. But the complete collection from Leroi-Gourhan’s mission has never been exhibited in its entirety.

In 1950, Leroi-Gourhan increased the Museum's collection to more than 130 religious prints and images. In 1951, he lent 16 objects (essentially masks and ema) which were finally donated to the museum in 1953, together with those from the first donation in 1947.

Some of the objects collected in Japan remain in the family collection, including pieces relating to the Ainu people. During the summer of 1938, the Leroi-Gourhan and his wife did indeed undertake a trip to Hokkaido to observe this ethnic group. In 1989, some time after the death of her husband, Arlette Leroi-Gourhan (1913-2005) published Un Voyage Chez les Aïnous: Hokkaido, 1938 (1989) about their stay. Finally, in 1998, she offered the Ethnography Museum in Geneva nearly 750 ofuda and printed plates collected by her husband in the years 1937-1939.

© Musée du quai Branly / Laboratoire photographique du Musée de l’Homme

Related articles

Personne / personne

Collection / collection d'une personne