ROHAN Louis de (EN)

Cardinal Louis de Rohan: A Certain Taste for China

The fascination for China that held Europe in its sway from the end of the 17th century through the Revolution gave rise to a vogue for porcelain cabinets, ceramics adorned with inventive gilt bronze mounts, in rococo and then in neo-greco styles, rococo chinoiserie in the manner of François Boucher, and, finally, Anglo-Chinese gardens filled with pavilions and pagodas with architecture inspired by the Celestial Empire.

Château de Saverne

Cardinal Louis René Édouard de Rohan-Guémené (1734-1803) was not immune to this mania for all things Chinese. Louis-René was the grand chaplain of France since 1777, cardinal since 1778 and prince-bishop of Strasbourg since 1779, following his election as bishop coadjutor to his uncle Louis Constantin de Rohan (1696-1779) in 1759. During the revolutionary era, Louis-René was the last in line of the four prince-bishops of Rohan who had succeeded each other without interruption since 1704 at the head of the prestigious diocese of Strasbourg.

This brilliant prelate divided his time between Versailles, where he benefitted from an official apartment through the grand chaplaincy; Paris, where the first Cardinal de Rohan had built the Hotel de Rohan-Strasbourg in 1705; the Château de Coupvray, located between Meaux and Lagny; and, finally, Alsace, where hehad several residences, in Strasbourg, Saverne, Mutzig, and Benfeld.

The two most prestigious residences were undoubtedly the episcopal palace of Strasbourg, which was built, decorated, and furnished from 1732 to 1742 following the plans of Robert de Cotte, first architect of the king, at the request of Armand Gaston de Rohan-Soubise; and the sumptuous country château of the bishops of Strasbourg in Saverne. Lavishly expanded by the prince-bishops of Furstenberg, this château and its vast gardens received spectacular embellishments commissioned by their successor, Armand Gaston de Rohan. On this project R. de Cotte unleashed the full measure of his art.

The day after his accession in 1779, the new Bishop of Strasbourg witnessed a great fire at Château de Saverne, which would continue for three days. The main building, which had been refurbished by the king's first architect at the request of Armand Gaston de Rohan, was completely destroyed. Cardinal Louis René decidedto undertake its reconstruction, which he entrusted to the architect Alexandre Salins de Montfort (1753-1839). This architect provided for the replacement of the main building with an enormous building 144 metres long. From then on, the facade on the side facing the park, rather than the city, was designated as the principal facade. Before it spread an immense park of several hundred hectares crossed by a spectacular recreational canal four kilometres long, set perpendicular to the main building and forming a perspective admired unanimously by contemporaries (Ludmann J-D., 1969).

Objects from the Far East

During the same period, the cardinal assembled a spectacular collection of objects from the Far East in Saverne, some of which would not have been out of place in a royal residence.

Founded according to principles of series and monumentality, the ensemble surprisingly stands out from the collections of the time. Exceptional in terms of their rarity, size, and the principle of series connecting them, these objects do not form a personal collection so much as a set of pieces meant to be integrated into decorative schemes, in the tradition of the court or princely collections.

This category includes, for example, the Imari decorative trim (Strasbourg, musée des Beaux-Arts (MBAS), inv. 33.978.0.33, 33.978.0.34, 33.978.0.35, 33.978.0.36, 33.978.0.37), three covered jars and two cone vases, among the high-priced large-format sets that would make up the bulk of Japanese Imari exports to Europe; two large vases with a powder blue ground (MBAS, inv. 33.978.0.25, 33.978.0.26), on a mahogany base in the shape of fluted columns by the Parisian cabinetmaker Garnier, likely from the sale of the collections of the Marquis de Marigny, director of the king's buildings and brother of the Marquise de Pompadour (Paris, 1782); or the extremely rare paired pagodas (MBAS, inv. XXXVI.116, XXXVI.117), inspired by the Nanjing porcelain tower, which have no equivalent in European collections in the 18th century (Martin E., 2008-2009 , pp. 124-127).

Two paintings under glass are equally exceptional both in size and in theme, portrayingscenes that are pointedly Chinese (Hôtel de Ville de Strasbourg, without inv.). Everything indicates a respect for conventions that is truly astonishing for paintingsthat were presumably intended for export. This also raises questions about the means of supply of this type of object, which at first sight would not seem meant for commercial exchange.

A valuable document kept in the Departmental Archives of the Bas-Rhin (AD 67, 1 V Evêché, 3) is essential for understanding the motivations and the context in which these purchases were made. Dated April 17, 1784 in Saverne, it is entitled Etat des nouveaux objets d’ameublements qui ont été mis au Château de Saverne depuis l’avenement [sic] de Monseigneur le Cardinal Prince de Rohan à l’Evêché. On three pages, under four chapter headings, it lists objects, works of art, and furniture that entered Saverne from 1779, the year of Louis René de Rohan's accession to the episcopal throne and the fire at the château. By comparing the list of objects grouped under the Porcelaine de la Chine to the revolutionary inventory dated 1790 entitled Inventaire des meubles et effets qui se trouvent dans le Château au dit Saverne (Archives municipales de Saverne, 410. effects…, p. 255-248), the ensemble as constituted in 1784 does not seem to havebeen added to the following years.

In 1790, when the commissioners of the Revolution inventoried the furniture and effects of the Château de Saverne, which had been declared national property, they counted more than 60 objects of Far Eastern origin in the storage room of the "château carré", a wing spared by the fire of 1779 that served as a temporary residence for the prince-bishop during his stays in Saverne. Since that same year, he had in fact accumulated and stored furniture and works of art purchased to replace what had disappeared during the disastrous fire, in order to furnish the new residence as soon as it was completed. Pride of place was reserved for acquisitions of objects "from China".

The Cardinal's Plan

More than objects of curiosity or a collection, these purchases made over the relatively short period of four years should rather be seen as the development of a clearplan. The wish to place these objects within the grandiose row of park-facing rooms planned by Salins had to be abandoned; not only had the practice of distributing Far Eastern objects throughout a residence gone out of fashion, but above all, the new château de Saverne was designed to be a total work of art, such that all elements (architecture, decor, works of art, and furnishings) needed to correspond in a perfect unity of neoclassical style.

The principle of unity, this time regarding the "objects of China", can be found elsewhere, within the park itself. In the 1750s, the taste for China was renewed by the new fashion of Anglo-Chinese gardens. In 1757, after ajourney of several years in the Far East, the English architect William Chambers published Design of Chinese Buildings: Furniture, Dresses, Machines, and Utensils, which was followed by writings on the art of gardens by other theoreticians who approached the Far East from the perspective of ethnography and fascination. In France, the publisher Georges Louis Le Rouge, in particular, saw to its distribution. The picturesque effects of these landscaped gardens were embellished with "fabriques" in the shape of a mosque, an Egyptian pyramid, a ruined Gothic castle, a pavilion, and a Chinese bridge, intended to surprise the visitor and simulate travel through space and time.

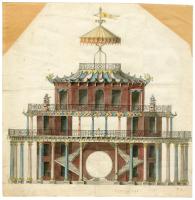

This quest for evasion found a particularly successful echo in Saverne, where at Cardinal de Rohan’s request Salins completed the château’s sumptuous project of reconstruction with a monumental Chinese pavilion. This was one of the most original creations among these extravagant "fabriques" commissioned to embellish the gardens of sovereign and aristocratic residences where the fascination for exoticism found favourable terrain. The Saverne pavilion did not appear at the bend of some path in the heart of a bucolic landscape, but constituted the visual culmination of the masterly axial perspective created by the pleasure canal and imposed itself on the view from the château itself. The edifice was established in the centre of the large circle of water, which interrupted the channel at a distance of 2.5 kilometres from its source, on a purpose-built island 75 meters in diameter (Martin E., 2008- 2009, pp. 58-77).

The pavilion, which broke ground in January 1783, was designed on an oval plan and comprised a garden level and three progressively shrinking floors, the last forming a terrace-belvedere. A portico in the form of a peristyle with 32 columns reigned over the entire circumference of the ground floor. It protected the stairs as well as the circular glazed entrances giving direct access to the oval living room. This was surrounded by four chambers. Its ceiling was pierced by an oculus giving a view of the ceiling of the first floor, with a painted decoration of light clouds among which could be distinguished "Chinese birds and particularly an eagle holding in its beak the chandelier cord".

The Chinese style of architecture was reinforced by red, celestial blue, yellow, and gold polychromy. The columns were enhanced with painted Chinese characters. Bells, dolphins, dragons, and Chinese musicians adorned the galleries and roofs. Chinese trellises, flowers, and shrubs were painted on the facades of the first and second floors.

Crushed glass sprinkled on the columns, roofs, and decorative elements allowed the pavilion to "sparkle" in the sun or during night illuminations.

"The Pleasures of the Enchanted Island"

The essence of Cardinal de Rohan’s plan can thus be grasped. The construction of the new château and the pavilionwerecarried out simultaneously, as were the purchases or the creation of furnishings according to the drawings of Salins, all stored in the old “château carré" while awaiting their designated placements at the appropriate time.

The motivations driving the cardinal, who took care to acquire objects often unknown in France, or whose decorations evoked scenes of Chinese life, even objects opposite to the dominant European taste, reveal a clear desire to elicit surprise and to give an authentic Chinese character to the pavilion and its furnishings. The "archaeological" concerns of Salins de Montfort, seeking to translate the architecture of the Celestial Empire as much by form, polychromy, and ornamentation as by the materials of construction (mainly wood and metal), bestow upon the building a tangible presence of the yet-distant Orient. What is more, the island of Grand Rond could be reached by boat or Chinese gondola via the canal from the château.

The patron and the architect combined their imaginations to go beyond the real. The cardinal's guests, led by the Duke of Northumberland, must have had an uncanny sensation of traveling into the unknown and, upon setting foot on the island and encountering the monumental pavilion with its bells tinkling in the wind, to have arrived in the land of the rising sun. Crossing the threshold of the ground-floor doors, the magic would continue. The pagodas and vases with monumental lids, the series of large balustrade vases, four in number, the large jars with blue and white decoration, the pair of large fish basins, the series of bottle vases with graviatabases, the three baluster vases embellished with Chinese scenes and figurines, the impressive "Outdoor Scenes" in painted and tinned glass, and the large porcelain statuettes and birds were among the most impressive objects in this set.

This edifice, at the centre of the architectural device, perfected thesensations of the unknown, novelty, discovery, and escape into a distant world which became physical through the intermediary of illusion so cherished at the time: the faraway residing at the very heart of the familiar.

Epilogue

The episcopal estate of Saverne, declared national property at the time of the Revolution, was quickly subjected to acts of vandalism and looting. Furthermore, the director of the national management of domains proposed the sale of the pavilion to the departmental administrators before the copper and the lead covering it could be stolen. It was finally decided to completely remove the pavilion to remove the lead, copper, and iron for the benefit of the national store of metallic materials in Strasbourg, which would be carried out during the summer of 1794. No less than 23 wagons wererequired for the transport of the lead.

The huge park quickly turned into wasteland and was gradually subdivided; the canal was filled in the 19th century. Only the Grand Rond has survived, deprived of its island, and has been under protection since 1923.

The only memory remaining of the ephemeral existence of this pure, monumental jewel (about ten years) lies in the ensemble of Far Eastern objects. Indeed, with the approach of the sale of the prince-bishop's property in Saverne, announced for March 18, 1793, the directoire du Bas-Rhin considered on February 12 "that it is important to ensure the execution of the law of September 16, 1792 which orders that statues, paintings, etc., worthy of being kept for the instruction and the glory of the arts (…) shall be sorted”. The fascination generated by these objects was at work once again and they were all transferred to the Museum départemental révolutionnaire in Strasbourg. The report accompanying the transfer, dated July 4, 1793, gives a complete and detailed list of the Saverne “collection”.

A number of pieces wouldlater be inadvertently removed due to accidents or disappearances linked to the turbulent historical events of the 19th century. From the Museum, the collection was transferred to the apartments of Napoleon I and Josephine at the Palais Rohan, which became imperial in 1806; there it remained under the Restoration and the July Monarchy. In 1852, the collections were transferred to Strasbourg city hall, at Place Broglie. From the 1930s, they gradually returned to the Palais Rohan, which became the Musée des arts décoratifs in 1919. Extraordinarily, for more than two centuries, the objects brought together by Louis René de Rohan experienced varying fortunes without ever leaving Alsace and without being dispersed. Their journey ended with their gradual inclusion, from 1936, in the inventory register of the Musée des arts décoratifs in Strasbourg.

Today, the exceptional collection of Far Eastern objects is distributed through the rooms of the Palais Rohan, the former imperial and royal palace in Strasbourg. The collection perpetuates the memory of this enthusiasm for China, which infatuated Enlightenment Europe and to which Louis René de Rohan managed to give shape in such an original way with the help of Alexandre Salins de Montfort.

Related articles

Collection / collection d'une personne

Personne / personne