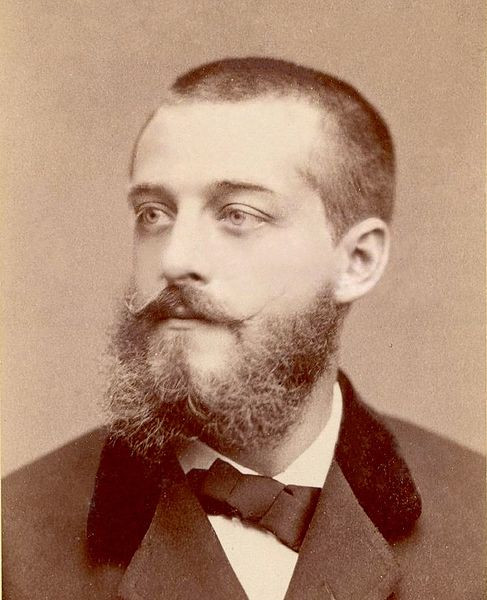

RÉGAMEY Félix (EN)

Biographical Article

Félix Régamey, neither an art dealer nor a major collector, nonetheless remains a particular figure in the history of Japonisme in France. This draftsman, caricaturist, and painter was a tireless transmitter of Japanese culture. He possessed an exaggerated enthusiasm not inclined to nuance, which helps explain why his reputation eventually fell into oblivion. This oblivion is unjustified, as he was integrated into the intellectual and artistic circles of his time, close to le groupe des Batignolles, particularly Henri Fantin-Latour (1836-1904), and a friend of Paul Verlaine (1844 -1896), whom he welcomed in London during his getaway with Arthur Rimbaud (1854-1891). Vincent Van Gogh (1853-1890) was full of praise for his engraving that appeared in the Illustrated London News, and in a letter to Anthon Van Rappard (1858-1892) in July 1883, Philippe Burty (1830-1890) lauded him as "a relentless tourist, a thoughtful draftsman, a dreamer intoxicated with logic [...] Japonisme all the way! But Japonisme interpreted, experienced, not merely copied.”

Born in Paris on August 7, 1844, Félix Elie Régamey was the second of three siblings; his brothers Guillaume and Frédéric also became designers and painters. Their father, Louis Pierre Guillaume, of Swiss origin and a printer-lithographer, introduced them to drawing, before sending them to the École spéciale de dessin et de mathématiques, where Horace Lecoq de Boisbaudran (1802-1897), author of a drawing method based on direct observation and memory, was a professor. Félix Régamey remained immensely grateful to this teacher and his attention to the individual development of his students; he honouredhis memory in a 1903 book, Horace Lecoq de Boisbaudran et ses élèves. Notes et souvenirs, published by H. Champion.

Félix Régamey published cartoons and caricatures in various newspapers and magazines, from La Vie parisienne to the Journal amusant, Le Boulevard, L’Indépendance parisienne, and Les Faits-Divers illustrés, and founded the short-lived Salut public (a single issue in September 1870). He frequented the dinners of the "Villains Bonshommes" and the Café Guerbois, a haunt of artistic Bohemians gathered around Manet and the Batignolles group (Jeancolas C., 2014).

Coming from a staunchly republican family, he joined the Légion des amis de la France pour la défense de Paris at the outbreak of the war of 1870. He sent some sketches of current events to his older brother, who was living in England because of his fragile health, and who managed to place them in the local press. Felix joined him just before the Commune and spent two years there before heading to the United States. Life was tough, the competition intense; he delivered drawings and caricatures, taught, and developed a show of publicly illustrated lectures which greatly impressed his audience. But his disconcerting ease, his speed in sketching and illustrating his remarks, in some ways did him a disservice and led him to be perceived as somewhat of a charlatan.

At this point, he joined up with Émile Guimet (1936-1918) in 1876, future founder of the eponymous museum. Guimet had been planning a long mission to Asia with the aim of studying its religions; he invited Régamey along in order to document the settings and to illustrate the places and highlights of this scientific investigation upon their return, as well as to serve as an interpreter. The first stop was Japan, which had long intrigued Régamey, who like everyone at the time was infatuated with prints. The shock of discovering this country would mark him forever: everything was admirable; everything was a pretext for pure joy. Travel notes, letters, and countless drawings taken from life reflect the fascination experiencedby the artist during the ten weeks of a journey that led from Yokohama to Kobe via Tokyo and Kyoto. Like all travellers to Japan, they went shopping: Guimet made purchases, primarily for ritual objects for the museum of the history of religions that he was planning to create, as well as for prints and albums; as did Régamey, to a lesser extent. They met an artist who was still little-known in Europe, Kawanabe Kyōsai (1831-1889); the two artists engaged in a friendly drawing competition, each sketching the other in his style. These portraits are among the many drawings that illustrate Émile Guimet’s account of their Japanese adventure, Promenades japonaises, publishedin two volumes in 1878 and 1880.

The rest of the trip, from China and on to India via Sri Lanka, was carried out in haste, as time was running short. After his over flow of delicate emotions in Japan, Régamey despised China, rediscovered his caustic spirit in India, but continued to make sketches, despite the often suspicious hostility of the Chinese crowds or the crafty nonchalance of certain Indian interlocutors. Back in Paris after their ten-month journey, the two men devoted themselves to their great work: Guimet established his museum of the history of religions, and Régamey created some 40 imposing paintings based on his travel notes and sketches. Above all, he revealed himself to be a tireless pilgrim of Japan and its culture, while professing a maniacal Sinophobia. Any pretext was enough to exalt the "real" Japan, from a scathing response to Pierre Loti (1850-1923), whose superficiality he deplored in his Madame Chrysanthème, to an illustrated edition of a translated work by Kyokutei Bakin (1776- 1848), which he called Okoma, published in 1883.

But he was still taunted by the travel bug; in 1879 and again in 1881, he returned to the United States for official missions; the first regarding the teaching of drawing in that country, the second as part of the delegation on the centenary of the battle of Yorktown. The artist collaborated with a number of periodicals, gave a series of illustrated conferences, painted portraits, even provided the subject for an issue of the magazine Les hommes d’aujourd’hui, ‘art does not feed the man’. He then decided to apply for a professorship at the École des arts décoratifs and at the École d’architecture, then for inspector of drawing education for the city of Paris in 1881. Japan inspired him endlessly, in Japon pratique (1891) then, thanks to an official mission, Le dessin et son enseignement dans les écoles de Tokio (1899), and finally in 1903 Le Japon en images (1891).

Sociable, and curious about everything, Régamey belonged to many societies, the sequence of which can be difficult to follow: the Société des amis des monuments parisiens; the Société historique du 5e arrondissement de Paris; the Société franco-japonaise de Paris, where he was secretary general since its foundation; the Société des traditions populaires, for which he sometimes illustrated the invitations to the dinners of "Ma Mère l’Oye"; and even the Société d’hypnologie et de psychologie, which inspired him to take a course on the psycho-sociology of art. Yet his incessant activity seems to have concealed a certain disarray. Relations with Émile Guimet became considerably strained, and collaborations with the museum - such as the illustration of the Fêtes annuellement célébrées à Emoui by Jan Jakob de Groot (1854-1921), or the lecture by Émile Guimet on Le théâtre au Japon (1886) - became less frequent. A Buddhist ceremony held at the Musée Guimet in 1898 provided the occasion for a final work, a delicate pastel representing the Buryat monk Agvan Dorjiev (1853-1938) before an assembly of gentlemen in dark suits enhanced by ladies in feathered hats and ribbons. Meanwhile, the museum archives reveal some rather pathetic letters from Régamey to Guimet, then to the curator of the museum Léon de Milloué. It was a matter of canvases that the artist did not know where to store, of which he then demanded the list. Another stumbling block, an arguably ill-considered marriage, ended in divorce after three years of deep disagreement. But the root cause of the disenchantment was certainly that Japonisme had died out, gone out of fashion. He set up a reclusive cabin in a courtyard between two buildings in the 5th arrondissement that was nestled in a tiny garden with plenty of lanterns, toriis and shrubs, where he devolved in a jumble of trinkets, prints, and albums.

Régamey's last years were both frenetic and lonely. He was very involved in his classes, the Société franco-japonaise de Paris, and various social reform projects, and he still found time to create the costumes for a Madame Butterfly by Puccini in the French version that was given at the Opéra-Comique in 1906, inspired, ironically, by the work of Pierre Loti (Ducor J., 2016). His already failing health deteriorated in the winter; he hoped to improve it in the mild air of Provence, but on May 5, 1907 he died in Juan-les-Pins. His studio was sold, his collections of prints, albums and objects dispersed; their excessively brief inventory does not allow the value to be properly assessed. This artist of sensitive sensitivity, the merry bohemian companion, the "madman of Japan drunk on colours" gradually disappeared from memory; only a few paintings and hundreds of sketches remain in the Musée national des arts asiatiques – Guimet, or scattered in museums.

The Collection

Félix Régamey's personal collection was dispersed shortly after his death. The sale catalogue does not provide precise information on the artist’s objects, albums, or prints.

From Félix Régamey’s production, some of the oil paintings executed for the Musée Guimet are still kept there; about 20 to date have been found and restored out of the roughly 40 that existed. These were published in the catalogue of the exhibition Enquêtes vagabondes in 2017. Most of them illustrate Guimet and Régamey's trip to Japan, with views of temples, such as Le Temple de Kiyomizu à Kyoto, rituals, such as La Tonsure des séminaristes dans le temple de Honganji à Kyoto, Prédications et offrandes dans le temple de Tenmangu à Kyoto, and Vêpres bouddhiques à Nikko. Several hundred drawings sketched on the go during the trip allow us to follow the genesis of the images. These drawings and some watercolours are also preserved in the museum, as well as the engravings published in the publications of travel stories from China and India. There are also three paintings dedicated to the part of the trip to the United States that were also published in the aforementioned exhibition catalogue.

Related articles

Collection / collection d'une personne

Personne / personne