MALINET Marie Antoinette (EN)

Biographical article

Marie Antoinette Schlotterer was born in Paris on November 26, 1811, to Jacques (or Jacob) Schlotterer and Victoire Catherine Gouffé (AN, MC/ET/XXVI/1427). She married Nicolas Joseph Malinet on July 20, 1830, a tailor (AP, 5Mil 2060 2945-2947). Little by little Nicolas Joseph abandoned his initial work for the sale of curiosities, and Marie Antoinette participated fully his activities. In the preface to one of the sales after the death of Nicolas Joseph Malinet, Charles Pillet described her as “a collaborator as intelligent as she is dedicated” (Pillet C., 1887, p. V).

From the 1850s, they built a collection essentially made up of Chinese porcelain and entrusted its inventory to Albert Jacquemart (1808-1875). He was a scholar and passionate amateur who, during the 1860s, would become a reference in terms Far Eastern porcelain.

We know little about the background of Marie Antoinette Malinet apart from that of her husband. The couple had a daughter, Camille, who died prematurely at the age of 9. A few years after the death of their daughter, they took in young Louise Molas-Page (1851-1892), then five years old, whom they raised as their daughter and who was adopted by Nicolas Joseph Malinet some time after Marie Antoinette’s death in 1881 (AN, MC/ET/XXVI/1427, from Abrigeon, notice Nicolas Joseph Malinet). On this date, Louise was already an adult and married to Henri Grimberghs, nephew of Nicolas Joseph Malinet and employee in his curiosity shop at 25 quai Voltaire. Marie Antoinette Malinet formed, with her husband, a solid team until death. A journalist emotionally write about the celebration of their golden wedding anniversary for their fifty years of marriage in the Church of the Trinity: “that day, […] they smiled like two newlyweds in the spring of life” (Bloche A., 1886, n.p.).

Perhaps because there little known about Marie Antoinette outside of her husband's activities, what remains would be caught up in the history of her husband’s initiate in collecting. Thus, the collection and publication of her collection of Chinese porcelain could have been interpreted as a strategy to promote her husband's commercial activities (Saint-Raymond, 2021, p. 247) even though no source allows us to verify the purchaser of the pieces during the sale. The minutes rarely indicate more than the surname. It is likely that Nicolas Joseph Malinet bought for his wife according to her indications in the same way that he would buy for customers. The preface to her collection’s catalogue presents the publication as a personal initiative of Marie Antoinette Malinet (Emery E., 2019, p. 92 n. 18). In addition, when Marie Antoinette lent her collection for the exhibition at the Oriental Museum in 1869, she was clearly identified, in the labels and in the press, as the owner of the objects presented, without any confusion being made with the activities of her husband (Burty P., 1869, n.p.). Also, if one studies the catalogue of the sale organized by Nicolas Joseph Malinet in 1863, it is clear that it does not have the scientific precision of the catalogue of porcelains that Mrs. Malinet had especially drawn up by Albert Jacquemart. While it is true that Marie Antoinette Malinet participated in her husband's activity and benefited from his social success to acquire her collection, it is possible and therefore necessary to grasp the particularities of her career as a collector (cf. commentary on the collection).

The will of Marie Antoinette Malinet provides little information to understand her life. The only provision it contains is to make her husband her universal legatee (AN, MC/ET/XXVI/1386). It was in Nicolas Joseph's will six years later that the spouses' plan to adopt Louise Molas-Page appeared.

Marie Antoinette Malinet died on February 28, 1881 at the age of sixty-nine.

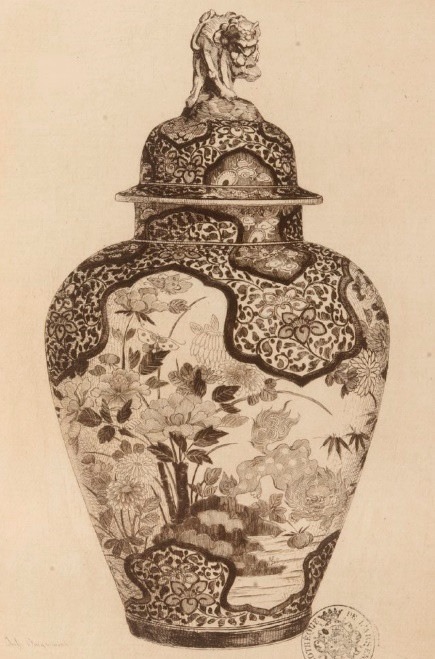

The catalogue of a specialist

Marie Antoinette Malinet’s collection is mainly composed of Chinese porcelain. We owe our knowledge of the collection to a publication in 1862 by Albert Jacquemart, who was an established expert in the field of Far Eastern porcelain. The book takes the form of a catalogue very similar to a sales catalogue, without illustrations, but rigorously classified by typology and accompanied by explanatory paragraphs for each category. The goal was to keep track of this publication. But their collaboration was not limited to the writing of the latter. Marie Antoinette Malinet made her collection (Blanc C., 1880, n.p.) available to Albert Jacquemart during the 15 long years of the writing of her first work on porcelain, co-written with her colleague Edmond Le Blant under the title, Industrial and Commercial Artistic History of Porcelain (1862, “Prospectus”, p. 2). And for good reason, the chapter dedicated to “Oriental Porcelain” makes numerous references to the collection of Marie Antoinette Malinet. A large number of works from her collection are also reproduced by Jules Jacquemart, Albert's son. If Albert Jacquemart favored the collection of Marie Antoinette Malinet to illustrate his work, it is most certainly because of the high quality of her works, their variety and their number. Marie Antoinette had, because of her husband's activity, a very significant purchasing capacity, at least much greater than that of Albert Jacquemart. He also had a collection that was essentially of small-scale works, sometimes cracked, but served as examples for his manner of classifying Chinese porcelain. It is therefore not surprising that, for the plates of his work, Albert Jacquemart referred to the collections of Marie Antoinette rather than his own.

The catalogue includes a total of 431 porcelains, the vast majority of which are Chinese. The classification is extremely detailed, and each category is explained by means of an introductory paragraph. After the so-called “historical” porcelains, that is to say inscribed (most of the time with the nianhao 年號reign mark), we find the main categories developed by Albert Jacquemart, namely: the archaic, chrysanthemo-paeonian families ( sic), green, pink, as well as exceptional productions (on this classification, see d'Abrigeon P., 2018). Added to this are categories that do not exist in the history of porcelain, such as that of “vitreous” or “imperial” porcelain (Jacquemart, 1862, p. 51-55). This last category “inspired, without a doubt, by the sight of European works, is completely different from the ornamental habits of the Orient,” says Albert Jacquemart (1862, p. 54). One might think the name of this category finds its origin in the sale of pieces from the Summer Palace, the Yuanmingyuan 圓明園, the palatial residence of the Qing emperors that was looted and then burned at the end of the Second Opium War (1860 ) by the Franco-British troops. But this is not the case for the descriptions always seem to echo export porcelain. Alongside Chinese porcelain, Albert Jacquemart also identifies Korean, Indian and Persian porcelain. However, the in-depth analysis of its classification using existing objects has shown that Indian and Persian "porcelain" was very often made in China for the Middle East or Southeast Asia, which implies a stylistic and formal difference being the base of Albert Jacquemart's error in expertise (P. d'Abrigeon, forthcoming). As for Korean porcelain, it corresponds to the kakiemon-style pieces produced in Japan for the Western market at the turn of the 18th century (d'Abrigeon P., 2020, p. 88). Finally, most of the “Japanese” famille rose porcelain are also most often Chinese.

Many provenances are noted in the catalogue which gives an idea of the timelessness in which the collection fits. It is therefore very likely that Marie Antoinette Malinet began her collection in the early 1850s. The oldest identified provenance contained in the catalogue is that of the sale of the Debruge-Duménil collection (1788-1838). Marie Antoinette Malinet probably did not make any acquisitions during the seven sales after the latter's death between 1839 and 1840 (Lugt 15279, 15324, 15586, 15640, 15701, 15963, 15994) – we find the name of her husband for a few purchases during the sales of March 10 and December 14, 1840, but nothing concerning Chinese porcelain (AP, D48E3 33, D48E3 34) – but rather during the sale of January 23 and 24, 1850 which brought together around fifty lots of Chinese and Japanese porcelain (about the sales of this collection, see Arquié-Bruley F., 1990). In 1853, during the sale of the painter Alexis Gabriel Decamps (Lugt 21350), "Malinet" - impossible to know if it is a question of sir or madam - bought a few varied objects, including "two Chinese cups with saucer" for forty francs, or “two Indian earthenware dishes” (lot 296) for thirty-eight francs (see annotated copy of the catalogue, BNF, YD-1 (1853-04-21)-8, report absent). Several pieces from the collection are still indicated as coming from the sales of the Duchess of Montebello, who had definitely directed Nicolas Joseph Malinet's trade towards objects from the Far East (d'Abrigeon P., notice Nicolas Joseph Malinet). During the large sale of works of art and paintings by Louis Fould in June 1860 (Lugt 25635) Malinet bought works of art of all kinds, including several cups, teapots, and plates in Chinese porcelain (AP , D48E3 51). Among the various origins still cited are the names of the chief inspector of the printing and bookshop Charles Henri Bailleul (sale of 1853, Lugt, 21294; AP D48E3 45), Augustin Pierre Daigremont (sale of 1861, Lugt 26072, AP D448E3 52), Hope, Humann, Madame Odiot, Poinsot (sale of 1861, Lugt, 26033), Richard, Horace de Viel-Castel. In addition, a piece comes from the old collections of Auguste le Fort (Frédéric-Auguste Ier de Saxe said, 1670-1733) kept at the Porzellansammlung in Dresden (no 234). Some pieces are also indicated as coming from the Yuanmingyuan, whose sales had started in Paris about a year before the publication of the catalogue.

The pieces received as donations also testify to the links maintained by Marie Antoinette Malinet with the collectors of her time. She thus received works from Tony de Berg, Barbet de Jouy (1812-1896), Baron Hippolyte Boissel de Monville (1795-1873), Baron Dejean, Paul Chevandier de Valdrôme (1817-1877, who sold his collection in 1862, Lugt, 26534, AP, D48E3 53), the Countess Tarragon and of course Albert Jacquemart.

1869: exhibition of the collection at the Oriental Museum

In 1869, the Central Union of Decorative Arts organized an exhibition entirely dedicated to the arts of the “Orient”, which brought together the private collections of a large number of collectors with the aim of providing models for industrial production. With some 312 numbers exhibited – including 297 Chinese porcelains – Marie Antoinette Malinet is one of the main lenders of this event (Saint-Raymond, 2021, p. 247). Her cases, Philippe Burty tells us, "contain the most varied and exquisite types [...] one will find in the Malinet collection almost all the shapes and all the tones, all the varieties of pastes and decorations that one can dream. This ranges from the most homogeneous and creamy "white of China" to the most original crackle, from “frog's back” green to aubergine purple, from the blue of the sky after the rain to imperial yellow and horse liver, from the cornet of 'a slender jet with a swollen vase almost like a Medici' (Burty, 1869, n.p.). Albert Jacquemart, responsible for covering the event in the Gazette des Beaux-arts, draws the reader's attention to the "great chimeras" in the color "violet-pansy", or even a vase "from the district of Tching- Ling” which he had already analyzed in his first publications (Jacquemart A. 1869, p. 484 and 486-487). The journalist Felix-Deriège in the daily Le Siècle (Oct. 25, 1869), mentions "among the most remarkable [pieces]" a "cup with blue decoration enhanced with characters and chimeras in round-bump biscuit" or even "a eggshell urn around which mandarins climb a series of mountains to make their offerings” whose “figurines and landscape are distinguished by the delicacy and perfection of the work”. The author also notices the so-called commissioned pieces made in China, the decorations of which are inspired by European engravings that are abundantly found in the collection of Marie Antoinette Malinet. It does not seem that Marie Antoinette Malinet continued to enhance her collection after this date, and it is even difficult to find traces of this collection in the inventory after her husband's death, as the descriptions are lacking (AN, MC/ET/XXVI/1427).

On the other hand, we find later descriptions of the collection by Edmond de Goncourt in the House of an Artist. He lovingly depicts a “plate whose rim has been cut off, representing a Chinese woman seated on a porcelain stool, one hand falling on a closed album, one hand carrying a fragrant flower to her nose with two children seated nearby. This small tray is of the finest quality of enamel, with its tender tones, its faded pink complexions similar to the first Saxony porcelain, with its fabric design which are, so to speak, colored only in the deeply etched billowing [sic] folds. This tray bears the number 150 of Mrs. Mallinet collection [sic], where this piece, a perfect Chinese piece, was classified by Mr. Jacquemart in the Japanese “pink family” (Goncourt E., 1881, vol. 2 p. 235). In addition to highlighting the progress made in the expertise of the works, this testimony indicates that during this period Marie Antoinette’s porcelain collection were put up for sale, most certainly at the shop at 25, quai Voltaire.

Unlike her husband, who owned a relatively heterogeneous collection, with contemporary paintings, medals, Far Eastern art objects and prints, Marie Antoinette Malinet assembled a collection essentially dedicated to Chinese porcelain. It was made know to the public by publishing it in the hand of the most recognized expert of his time and by exhibiting it masterfully on the occasion of one of the most important meetings of the Central Union of Decorative Arts.

I address my sincere thanks to Elizabeth Emery, who encouraged the writing of this notice, and enriched it with her precious proofreading.

Related articles

Personne / collectivité

Personne / personne