NOTOVITCH Nicolas (EN)

Biographical Article

Today, the name of Nicolas Notovitch is solely associated with his work La Vie inconnue de Jésus Christ (The Unknown Life of Jesus Christ) (Notovitch N., 1894) and with his numerous descendants in "modern apocrypha" (Mayer J.-F., 2007, see also and among others, Bouchet Ch., 2004 and Prophet E., 1984). In his book, published in French in 1894 by Ollendorff and immediately translated into several languages (including Russian in 1904), the author briefly recounts his trip to India and his stay in 1887 at the monastery of Himis (Ladakh), where he collected oral accounts and a Tibetan manuscript relating to the fifteen years that Saint Issa (Jesus) is said to have spent in India and Tibet from the age of fourteen to twenty-nine (BnF, 4-impr or-1013). The rediscovered manuscript, written according to the author by Buddhist monks from the death of Jesus and thus well before the Gospels, holds Pontius Pilate solely responsible for the arrest and crucifixion of Christ and does away with the theme of the resurrection, explaining that the body had been moved by the Romans without the knowledge of the crowd finding that his tomb was empty. This publication was widely commented on in the press and often severely denounced by theosophical (Mead G., 1894), Catholic (Giovannini R., 1894), rabbinical (Deutsch G., 1896), and orientalist circles (Blind K., 1901, Douglas J. A., 1896 and Max Müller F., 1894). They had previously contradicted the declarations of Helena Petrovna Blavatsky (1831-1891) in the journal Nineteenth Century. Blavatsky was the celebrated founder of the Theosophical Society and claimed to have received revelations on primordial Buddhism from the mahatmas that had been retired to Tibet. In a letter from October 4, 1892 to Jules Simon (1814-1896), from whom he seems to have obtained political as well as literary support, the author recounts having heeded his advice and shared his discovery with Ernest Renan (1823-1892), the famous author of La Vie de Jésus (1863), who had died on October 2. The latter dissuaded him from publishing his translation of the manuscript, explaining that his own thesis was supposedly on the ground by it (AN, 87/AP/5). Notovitch, on the other hand, claims in La Vie inconnue, that Renan wished to claim for himself the expected success of the discovery, a reason that would have led him to wait for the scholar’s death before publishing his translation. Although assigned to the “rationalist" camp by his critics (Giovannini R., 1894), it seems that Notovitch sought above all to throw a stone into the Renanian pond: concealing the obvious models of his approach, he followed Renan's idea of reconstructing the "origins of Christianity" from the life of Jesus, an idea at the source of many variations (Kaempfer J., 2008). However, Notovitch’s critique relies less on a plausible philological basis (the years that Jesus would have spent with Essene communities) than on a plausible orientalist one (the historical anteriority of the doctrine of the Buddha over that of Christ whose supposed resemblances are explained by direct contact) and an epistemological shift to India and Tibet with lasting fortune in esoteric, artistic, and literary circles (Thévoz S., 2016). In so doing, Notovitch echoed a famous model (Jacolliot L., 1869) revived shortly before him by works with theosophical tendencies such as those of Saint-Patrice (1854-1898) (Harden-Hickey J., 1891; note also that several of the author's books, including his Théosophie (Harden-Hickey J., 1890), kept at the BnF, come from Renan's library). The idea had been widely relayed by the press, in particular by an interview in Le Siècle with Léon de Rosny (1837-1914), reproduced in countless newspapers in France and abroad: the scholar, a figure in Asian and Buddhist studies and respected in public opinion, presented as possible the "augmented" Essene hypothesis that Christianity was a derivative of Buddhism and that Jesus benefited from Indian revelations (Rosny L. de, 1890). In terms of Orientalism, it is clear that Notovitch's story translates the atmosphere of fin-de-siècle Paris much more clearly than any ancient Tibetan source. Regarding the mysterious manuscript at the source of the story translated by Notovitch, the most attractive and plausible hypothesis has been put forward by Norbert Klatt (Klatt N., 2011, p. 74): in Ladakh, the traveler would have seen the pamphlets on the life of Jesus translated into Tibetan by the Moravian missionaries settled in this region and would have been inspired by these authentic documents, which Ladakhi interlocutors might have presented to him and whose provenance he had not identified, in his "translation" of the account of Saint Issa's life in India and Tibet told by Buddhist witnesses.

In 1894, Notovitch already had a fairly long career as a journalist and writer behind him. From this perspective, the publication of La Vie inconnue is astonishing, compared with the works in Russian dedicated to patriotic and political issues (Patriotism: Poems, 1880, Biography of the Glorious Russian Hero and Commander, the Adjutant Infantry General Mikhail Dmitrievich Skobelev, 1882, The Truth about the Jews, 1889, Europe on the Eve of War, 1890) and in French dedicated essentially to the Franco-Russian rapprochement (see bibliography below). His trip in 1887 also prompted several publications in Russian (Quetta and the Military Railroad through the Bolan and Gernai Passes, 1888, Where is the Passage to India?, 1889), while an account of the trip, which is mentioned here and there, never appeared in French: thus his A travers la Perse, relation de voyage illustrée was said to be "in press" in Europe and Egypt in 1898 (Notovitch, N., 1898) and again eight years later in his last book, published in French, La Russie et l'Alliance anglaise (Notovitch N., 1906). Here the list of "to appear" is increased by "Through India". The titles of other genres of works that were probably never published also appear alongside these two travelogues: Gallia, drame historique; La Femme à travers le monde, études, observations et aphorismes; Un bâtard couronné (les aventures de l’ex-roi Milan).

Despite the controversial reputation that the author’s 1894 publication aroused, little clear biographical information is available about Nicolas Notovitch. In the Catalogue général de la librairie française, he is succinctly mentioned as "Russian journalist, writer and explorer, born in Crimea in 1858" (Lorenz O., 1891, p. 772). There follows a card in the name of the "brother of the previous", O[sip]. K. Notowitch, Marquis O'Kvitch (or O'Knitch), "Russian journalist, born in Crimea in 1847" and author of three works of philosophy translated from Russian into German and French between 1887 and 1893 (La Liberté de volonté; Un peu de philosophie, sophismes et paradoxes; L’Amour, étude psycho-philosophique) as well as editor of Nowosti (Russian press agency; according to the Revue indépendante de littérature et d’art, 1898, p. 354). Had he also settled in France? There is no proof, but the journalistic endeavours of the two brothers clearly appear linked.

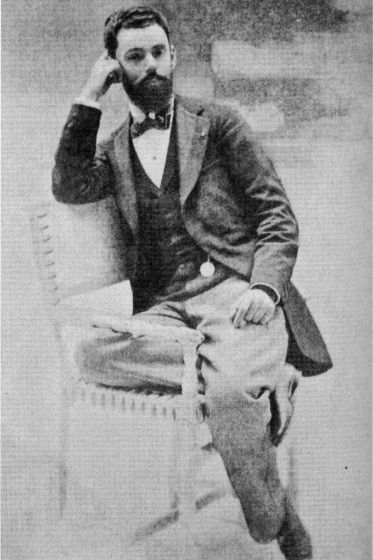

In prefaces to recent reissues of La Vie inconnue, commentators supplement these meagre data with a few biographical sketches, without always specifying their sources. Below, we reproduce the only reliable historical biographical notice on Nicolas Notovitch (possibly written himself), which appeared in the Dictionnaire national des contemporains:

“Writer and traveller, born in Kerch (Crimea) on August 13/25, 1848 [corrected: 1858]. After studies in Saint Petersburg, he served in the Russian army and participated in the campaigns of Serbia and Turkey from 1876 to 1878. Starting in the press as a correspondent for Le Nouveau Temps en Orient (1883), he then made several ethnographical voyages in Arabia, Persia, Central Asia, Afghanistan, India, Kasimir [corrected: Kachmir], and Tibet. In 1894, Mr. Nicolas Nottovich [corrected: Notovitch] published a sensational work on the Vie inconnue de Jésus-Christ, which was translated into all languages and aroused great controversy. This publication led to his being sent, by decision of the Russian Council of Ministers, to Siberia, wither he went voluntarily in 1895 and whence he returned in 1897 to settle henceforth in Paris. He was there by 1889 and had published notable articles in the Parisian press, notably political studies in the Journal, from 1892 to 1896. [Following is a list of published and forthcoming works by the author; added: Mr. Notovitch has since 1897 been directing the political and economic review Russie.] Member of the Société d’histoire diplomatique, honorary member of the "Combattants de Crimée," etc., he was named Officer of Public Instruction in 1889 for having donated valuable collections of objects brought back from India and Persia to the Musée du Trocadero. He is a grand officer and commander of orders of Russia, Bulgaria, etc.” (Curinier C.-E., 1901, p. 274).

Supplementing this note with archival documents, Norbert Klatt (Klatt N., 2011) documented Notovitch's youth in Russia and the years up until 1916 spent between France, Great Britain, and Russia, during which Notovitch distinguished himself as much as a linchpin of Franco-Russian agreement, at the time of the "Great Game" (Hopkirk P., 1992), as of Anglo-Franco-Russian, as a curious political intriguer known to the English and German secret services (besides Klatt, see Gooch J., 1929, Schwertfeger B. 1919 and 1921). In 1916, Notovitch was editor and publisher of several St. Petersburg newspapers.

This portrait is complemented by other archival documents that were not at the disposal of Klatt, who certainly undertook the most complete and convincing of all biographical accounts. First of all, exchanges of letters with Jules Simon and with Alexandre Dumas fils (1824-1895) (BnF, NAF15666, F.515-516) testify to the insertion of Notovitch in the overlapping political and artistic circles of Paris in from 1892. Bolstered by the publicity generated by La Vie inconnue, Notovitch sought to launch L'Horizon, a “review of literature, fine arts, history, geography, science, etc.” in 1895, which was open to young authors and supported by big names, some of whom were among the prestigious signatories of his Livre d’or à la mémoire d’Alexandre III (Notovitch N., 1895). The Archives nationales also preserve the request for a scientific mission sent by Notovitch to the Ministry of Public Instruction in 1890 (AN F/17/2995). This request, filed on February 6, 1890, described the project of an "exploration of the course of the Brahmaputra and of Lake Pangong at Lassa [spelled "Zassa" by the agents of the ministry]”; the project planned to explore the ancient trade route from Tonkin to Tibet. Alleging eight years of travel experience in the Orient, during which he had "systematically studied these countries", Notovitch did not hesitate to recall that the gift of his collection in 1889 had earned him the appointment as an officer of public instruction. Despite support from the Minister of Public Instruction, Armand Fallières (1841-1931), who underscored the Russian traveler’s loyalty in the service of France, the request was nevertheless rejected after consultation with the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Alexandre Ribot (1842-1923), who had entered into an agreement with Alexander III's Russia (1845-1894) and had emphasised that Notovitch did not have French nationality. Did Notovitch subsequently apply for naturalisation? Biographers assume this on the basis of several concordant testimonies from 1893 (Klatt N., 2011, p. 22), but no formal proof has been found to date. The Archives nationales also records a national security file under the name "Nicolas Notovitch" (AN, 19949464104); yet the documents, dated 1929, concern a certain Eugenie Notovitch, born in 1882 in Saint Petersburg, whose link with our author is impossible to establish.

A last file of letters helps complete our knowledge of Nicolas Notovitch’s path. In three letters from 1935 and 1936 addressed to Gabriel Hanotaux (1853-1944), with whom Notovitch had already been in contact in 1898, as a "modest Russian man of letters", when Hanotaux was Minister of Foreign Affairs, Notovitch discusses his literary activities and the founding of the Franco-American Commercial League. Included is a letter of recommendation (April 3, 1933), signed by Marshal Philippe Pétain (1856-1951) and Georges Leygues (1857-1933), regarding the promotion of Notovitch, who had already been decorated with the Croix d’officier de la Légion d’Honneur, "in recognition of his persistent action in the service of France". The letter points out that “after the misfortune that struck his homeland, Russia [in 1917], Mr. Notovitch settled in France, which he considers his second homeland. He devoted his forces and his political and economic experience to France.” Above all, the letter provides information on Nicolas Notovitch’s former activities in the entourage of Tsar Alexander III and as secretary of the League of Russian Patriots, which worked directly for the rapprochement of France and Russia. Notovitch also established copyright in Russia on the French model. It was Notovitch who is said to have convinced Tsar Nicolas II to award the Cross of Saint-Georges to the city of Verdun in 1916. After the end of the war, Notovitch distinguished himself above all in the context of commercial agreements between France and the United States, through the creation of the Franco-American Commercial League devoted to the promotion of French luxury products, wines, and spirits, as well as the promotion of French culture through the organisation of artistic exhibitions, conferences, and international student exchanges. The League, based in New York and Paris, published a journal, L'Horizon franco-américain littéraire et économique. Accompanying his letters, Notovitch sent copies of his last three books to Hanotaux, dating respectively from 1898, 1899, and 1906, with the justification: “I see that the events of today have a psychological analogy with the events of in the old days."

The Collection

Considering the rejection of his request for a scientific mission filed in 1890 with the Ministry of Public Instruction and Fine Arts, the only collection of Asian art known to have been assembled by Nicolas Notovitch must have been carried out during his 1887 trip to India and Ladakh, apparently at his own expense, before any established relationship with France. The collection nevertheless testifies that this trip was decisive in the French turn of Notovitch's trajectory and in this respect sheds important light on the famous publication in French of La Vie inconnue de Jésus Christ (Notovitch N., 1894). Likely written in the second half of 1892 (Klatt 2011, p. 65; AN, 87/AP/5), this account adds an unexpected literary lineage to the collection, seven years later. Unknown to modern readers of La Vie inconnue, whether skeptics or apologists, this collection thus stands out as the only tangible testimony of Notovitch's journey to the borders of northern India and western Tibet.

The collection primarily includes everyday household objects and musical instruments from Ladakh, Kashmir, Punjab, Sind, Afghanistan, Nepal, and Indochina, supplemented by a few cult objects from Tibet. Details on the collection methods are not known. There is neither the famous Tibetan manuscript found and copied at Hémis, nor the stone bearing the engraved inscription “Om mani padme hum” mentioned in La Vie inconnue (Klatt 2011, p. 48).

Without any explanation as to reasons, Notovitch's intention was initially to offer his collection to a French museum through the French consul in Bombay. Consulted by the Ministry of Fine Arts in February 1888, the secretary of the Société de géographie, Charles Maunoir (1830-1901), asked Gabriel Bonvalot (1853-1933), an explorer who was already famous for his travels in Africa and Central Asia, to appraise the three collections. To this end, Bonvalot indicated the Musée ethnographique du Trocadéro and recommended awaiting the arrival of Notovitch, who was then in Persia, before opening the boxes, as the Russian traveler would certainly bring back further interesting items. Although anticipated, this addition to the donation was not documented. It should be noted that, no doubt after this first indirect exchange, Notovitch mentioned Bonvalot as a friend in La Vie inconnue de Jésus Christ.

Overwhelmed by the mass of objects deposited within its walls, the Trocadéro museum gave away many Asian collections in 1900, which it intended for the Musée Guimet. But from this set Émile Guimet (1836-1918) retained only a few objects: like other collections (those, for example, of Charles-Eude Bonin (1865-1929), Charles de Ujfalvy (1842-1904), Henri d'Orléans (1867-1901), and Léon Dutreuil de Rhins (1846-1894), that of Notovitch was thus deposited in the Musée ethnographique de Bordeaux (collection "Ethnographie du Petit-Tibet") and can currently be found in the Musée du Quai Branly.

In 1889, Notovitch was recognised for this gift with academic honours as an Officer of Public Instruction. In the various letters from the author that we have been able to locate and in his mission application file, Notovitch, in the absence of French nationality, allowed himself through this gift and the decoration that he thereby earned to establish his loyalty to the "beautiful Gallia". The diplomatic motivations for the donation of the collection of a Russian Francophile writer-journalist, whose official and unofficial activities were to have a lasting impact on the artistic and political circles of the French capital, are thus revealed.

Related articles

Collection / collection d'une personne

Personne / personne