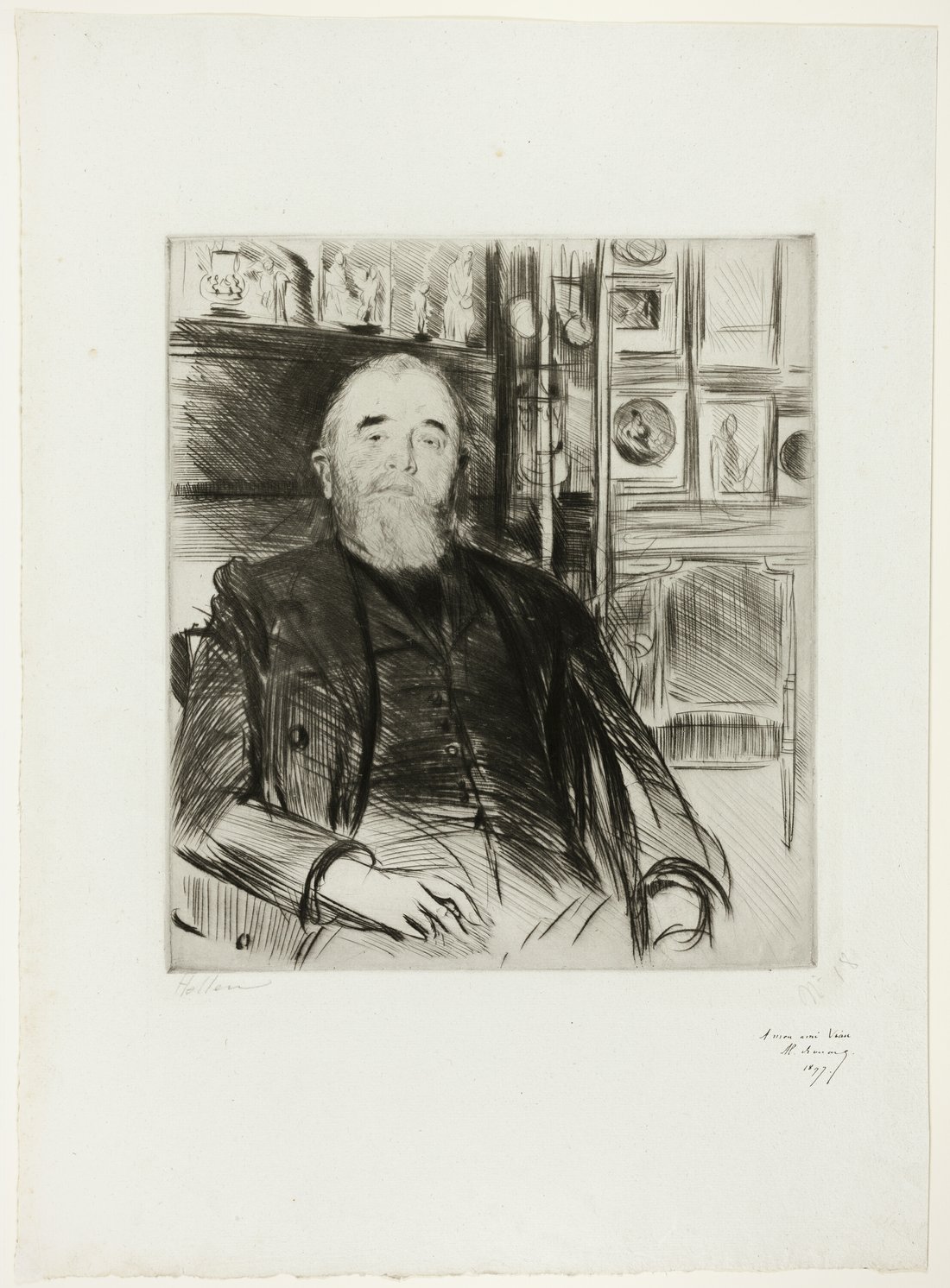

ROUART Alexis (EN)

Biographical article

Alexis-Hubert Rouart was born on March 21, 1839 in Paris, in an apartment on rue de Richelieu. His father, Alexis Stanislas Rouart, was the first of this family from Aisne to settle in Paris in 1816 (Rey J. D., 2014, p. 8). There he found a trimmer and embroiderer uncle and in turn became a trimmer specializing in army uniforms. In 1832, he married Rosalie Charpentier (1814 1889), mother of Alexis.

A rewarding engineering career

Alexis grew boarding at the Lycée Louis-le-Grand alongside his brother Henri (1833 1912). He obtained his baccalaureate there and studied law at the Faculté de Droit in Paris. He then trained as a mechanical engineer at the École Centrale and joined his brother in the company he founded in the late 1850s with Jean Baptiste Mignon. Mignon et Rouart (Rouart frères & Cie from 1885), headquartered on Boulevard Voltaire, specialized in motors and refrigeration systems. In 1866, the Rouart brothers opened a second factory, for hollow iron tubes, in Montluçon. From the 1860s to the end of the 1890s, the company received numerous prizes and medals at exhibitions in which it participated in France and abroad (Haziot D., 2001, p. 18 25). Several catalogues, memoirs or reports written by Alexis Rouart's proved his involvement in the company's innovations (Rouart A., 1889).

A family environment influenced by the arts

From childhood, Alexis Rouart frequented the military painters of the time and discovered their paintings in their workshops. These painters were Charlet (1792 1845), Raffet (1804 1860), Vernet (1789 1863) or Lami (1800 1890), whom Alexis' father rubbed shoulders with and from whom he commissioned drawings to sew his trimmings. In 1847, the Henri and Alexis father commissioned Auguste Bonheur (1824 1884) to paint a portrait of his sons, now kept in Pau (MBAP n.inv. 899.10.1). During the painting of the portrait, the Rouart sons took required drawing lessons in highs chool and rubbed shoulders with the likes of Degas (1834 1917) and Caillebotte (1849 1894). Alexis’ brother Henri trained in painting with Millet (1830 1906) and Corot (1796-1875) upon leaving high school and joined the group of Impressionists as of his first exhibition. In 1865, Alexis married his first wife, Amélie Lerolle (1845 1882), niece of the painter Henry Lerolle (1848 1929). Henri Rouart married the descendant of a large family of cabinetmakers, Hélène Desmalter (1842 1886). The best friend of the family is none other than Degas (1834 1917). After losing sight of each other upon leaving high school, Alexis, Henri and Degas all found themselves assigned to Bastion 12 during the Paris Commune in 1870. This reunion marked the beginning of a great friendship between Degas, the two brothers , and the rest of the family. He wrote Alexis in 1904, speaking of the Rouarts: “you are my family” (Guérin M., 1945, letter 235, p. 238). Their shared interest in collecting as well as for art and engraving are at the heart of the correspondence between Degas and Alexis.

Henri and Alexis Rouart

Henri and Alexis were very close and share their professional and social lives, their interest in art and their interest in collecting. Alexis lived for a time in an apartment near the factory, boulevard Voltaire, then moved to the private mansion occupied by his parents, built by Degas' brother-in-law, that adjoined that of Henri. The two brothers and their friends meet every Friday evening at Henri's, and every other Tuesday evening at Alexis'. The first works by the Rouart family, which have remained particularly discreet in the art history, begin to appear at the beginning of the 21st century. But within the small family history, it is Henri and his descendants who constitute the memory of the Rouarts. Alexis Rouart, seen as "less brilliant" than his brother (Haziot D., 2001, p. 30), found it difficult to dissociate his image from that of Henri, whose professional success, talents as a painter and extensive collection were the pride of the family.

A key actor in the network in promoting artistic knowledge

Member of the Société des Amis du Louvre, the Amis de Versailles and the Art Français, Alexis took part in the artistic life of the time. He was also “one of the oldest members of the Union Centrale des Arts Décoratifs, of which his father-in-law Henry Lerolle had been one of the founders” (Lemoisne P. A., 1911, p. 13). As an honorary member of the Société des peintres‑graveurs français, he participated in organizing Parisian exhibitions that promoted the art of lithographs by 19th century artists. Alexis Rouart took part in these same networks but for Japanese art. He was invited every Sunday morning to the collector Henri Vever (1854 1942) and participated at the Japanese dinners organized every month by Siegfried Bing (1838 1905). He was elected member of the Conseil de la Société franco-japonaise of Paris on many occasions, and then worked actively to promote Japanese culture in France and in Japan. Upon his request, the Society sent French books to Japanese universities (Société franco-japonaise, September 1911, p. 30). Hayashi Tadamasa a Japanese who came to settle in Paris for the Universal Exhibition of 1878, is one of the main pillars of this circle of Japanese amateurs. He was a close friend of Alexis as seen by their correspondence (Koyama Richard B., 2001). The two men met around 1880, perhaps when Hayashi arrived in 1878, or when he opened his first art store in 1883. This encounter could be at the origin of Alexis' interest in Japanese art.

The collection

Alexis Rouart and French art

Alexis began his collection of Western art when, at the age of eighteen, he acquired his first “romantic” lithographs (Lemoisne P. A., 1911, p. 6). He fell in love with this art and this period, works that make up the vast majority of his collection of Western art. Alexis accumulated the most beautiful proofs of Géricault (1791 1824) and Delacroix (1798 1863) restricting his interest in these two artists to their graphic works. He abundantly collected the rarest and most unique prints of his friend Degas. Passed into the hands of his son Henri after the collector's death, most joined the collections of the Estampes et de la photographie la Bibliothèque Nationale. Let us mention Après le Bain (inv. RÉSERVE DC-327 (DH,7)-BOITE EC) which the artist produced around 1891, or Les Deux Danseuses, an aquatint from 1877 (inv. RÉSERVE DC-327 (DH,4) -ECU BOX). Alexis' son donated these two works to the BNF in 1932. La Sortie du Bain is in the Harvard Art Museum (Fogg Museum, M26274). Degas produced this drawing with an electric pencil at his friend Alexis' house, around 1882. It was the first time that Degas experimented with this type of pencil, and one of the first times that he depicted a woman in the bath. In painting, Alexis was attached to the art of artists to who have little mention in art history, such as the romantic artists who remained in the shadow of their leaders. He devoted a particular affection to the military painters who formed his visual culture. The works of Eugène Lami are among the most numerous in his collection. L’Entrée de son A. R. la Duchesse d’Orléans aux Tuileries painting was acquired by the Louvre Museum after the collector's death (inv. RF 1775). Surrounded by impressionist artists in his social and family life, Alexis retained the majority of works from those “discreet and ambiguous” members of the group, such as Cals (1810 1880), of which the Rouarts are the rare patrons.

Japanese prints

So devoid of value in Japan, Japanese prints created enthusiasm amidst Parisian collectors from their arrival in France in the 1890s (Saint-Raymond L., 2016). After his death, his collection of Japanese prints amounted to nearly a thousand prints. These were not sold with the rest of the collection after his death in 1911, but passed into the hands of his brother Henri, who kept them, hanging them in his private mansion. They then moved into the possession of an American collector who organized their sale in New York in 1922. The Metropolitan Museum acquired several proofs that had belonged to Alexis Rouart during the sale. Tago Bay near Ejiri on Hokusai's Tōkaidō or Midnight: Sleeping Mother and Child by Utamaroare among the museum purchases.

An interest in Chinese and Japanese objets d’art

This love of Japanese prints did not prevent Alexis Rouart from taking an interest in Chinese and Japanese artwork. Japanese lacquerware, inrō, netsuké and tsuba are represented in the hundreds in the collection. His collection of tsuba is particularly recognized within the world of Japanese art lovers of that century. Its breath and quality earned it an analysis by the Marquis de Tressan (1877 1914), a great specialist, who wrote the preface to the catalog of their sale after the death of Alexis. In the 1890s, Kœchlin (1860 1931) was convinced of the "undeniable superiority of Japan" and stated his reluctance, and that of the collectors around him, of the interest in Chinese art: "nothing that was Chinese crossed the threshold of our collections". He adds that "only Alexis Rouart, Isaac de Camondo and Gonse were exceptions" (Kœchlin, p. 64). Alexis Rouart created a rich collection of bronzes, precious materials, cloisonné enamels and Chinese porcelain. His interest in extra-Western art extended to miniatures and objects from India and Persia which further enriched his collection. Following a visit to Alexis Rouart in 1908, Paul-André Lemoisne (1875 1964), who was Archivist then Conservateur Directeur Cabinet des Estampes of the BnF, published an article on the inventory of Alexis Rouart's collection and described his most exceptional pieces.

Building a collection

Accustomed to the Hôtel Drouot auction rooms, the creation of Alexis Rouart’s collection resulted, above all, from the relations he maintained with the Parisian art dealers of the time. Hector Brame or Paul Durand-Ruel (1831 1922) are among his main suppliers. In 1883, Alexis Rouart bought L’Atelier de la Modiste by Degas from Durand-Ruel for 3,000 francs which became the most beautiful piece of his collection of Western art according to Haziot (2001, p. 30). But it is in the stores selling Chinese and Japanese that Alexis Rouart spends most of his time and forges his greatest friendships. Speaking of Hayashi's shop, Kœchlin remembered that Alexis Rouart "made a detour there to get some fresh air when he left his metallurgical workshops" (Kœchlin R., 1930, p 19). He is also one of the most loyal customers and friend of Florine Langweil (1861 1958). Kœchlin describes the Chinese art objects that “almost every day he [Alexis] brought back from a visit to Mme Langweil” (Kœchlin R., 1930, p. 37).

The collection and its influence

Alexis Rouart is the "first donor" of sheet prints of the Départment des éstampes of the BNF (Lambert, 2009). In 1894, he donated seven of his Japanese prints to the Louvre Museum (AN, 20 144 787/16) and then inaugurated the museum’s collection of Japanese prints from the Edo period, accompanied by a group of Japanese art lovers. Alexis Rouart provided these institutions, as well as the Musée des Arts Décoratifs and the Musée Guimet, with donations until 1905. His second wife, Augustine Pipaud, originally from Creuse, took him to the Guéret art and archeology museum. He became one of its main benefactors and, between 1892 and the early 1900s, separated with more than a hundred pieces from his collection for the benefit of the museum. The prints, pottery and Japanese sword guards, the statuettes from China and Japan from its collection introduced Asian art to the Guéret museum. Noted as well is the large collection of chawan bowls donated to the museum by Alexis Rouart, originally used for preparing, serving and tasting tea during Japanese tea ceremonies. Some of them were made in the 17th century by the potter Ninsei Nonomura, such as the one representing a lobster (inv. B 076), a popular motif in Japanese art and a symbol of longevity. We can also mention a very beautiful little Japanese domestic altar in lacquer and gilded wood, in which is the statuette of the god Atago-Gongen (inv. 2010.0.25), or even a bronze incense burner in the shape of Qilin, all most certainly came from China (inv. B 231).

Related articles

Collection / collection d'une personne

Personne / personne