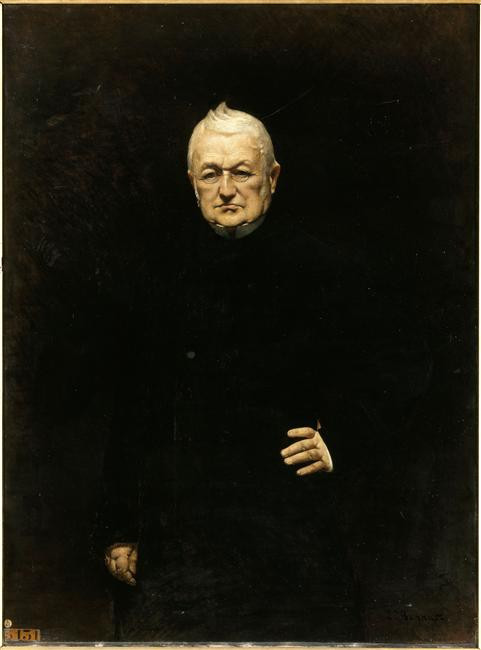

THIERS Adolphe (EN)

Biographical article

Marie-Joseph-Louis-Adolphe Thiers was born in Marseilles on April 15, 1797. He came from a bourgeois background, but his father, Pierre-Marie-Louis Thiers, had a particularly dissolute life, accustomed to shady business deals and to bankruptcy. Identified as gifted by his high school teachers, Adolphe went on to study law in Aix-en-Provence. He succeeded brilliantly in his studies and became a lawyer in 1818. In 1821 he moved to Paris with no income and no assets, yet as a gifted writer he found work at Le Constitutionnel and other newspapers. In 1830, he founded Le National and made a name for himself by writing on multiple subjects, mainly political ones. He was also interested in art, wrote about the Salons and was one of the first in 1822 to support the young Eugène Delacroix (1797-1863). He became friends with the Dosne family in 1827, who would become his adoptive family. The head of the family, Alexis Dosne (1781-1849), was a stockbroker. He was going to sell a building on credit to Thiers. This provided him with an income allowing him to be eligible in the property-based electoral system of the time. In gratitude, Thiers had him appointed receveur général in Brest then in Lille. Alexis Dosne therefore did not reside much in Paris and Thiers found himself alone with Mme Dosne mother (1794-1869) and her two daughters Élise (1818-1880) and Félicie (1823-1906). He would marry Élise in 1833.

From 1833, he resided in the family mansion on Place Saint-Georges. The satirical press suggested that he had a liaison with his mother-in-law and his sister-in-law (Valance G., 2007, p. 151-155). This same press never spared Thiers and mocked him during his very long political career, notably through caricatures (e.g. “Un parricide”, plate no. 106 of the Actualités series, Honoré Daumier, April 16, 1850, BNF, département des Estampes et Photographie, inv. Res. Dc-180b (40)-Fol.). He is mocked for his small size, his unattractive physique and his bad manners.

In essence, he wass mainly ridiculed for his ambition and his propensity to change sides. He was credited with various corrupt practices. He was hated by the left wing for his defense of the bourgeois order and his political decisions were perceived as hostile to the people (support for the suffrage censitaire), and particularly the repression of the revolt of the Canuts in Lyon in 1834 or of the Commune during the War of 1870 (Valance G., 2007).

Thiers would quickly begin a political career after having made a name for himself as a historian with the publication of the first volumes of his Histoire de la Révolution française in 1823-1824. It was a huge success, ten volumes would be launched with the last in 1827. This would earn him his election to the Académie Française in 1833. He would then write from 1845 to 1862 twenty volumes of a Histoire du Consulat et de l’Empire, which also enjoyed great success in bookstores and numerous reissues. He was elected deputy of Bouches-du-Rhône in 1830, re-elected until 1848 (Guiral P., 1986, p. 585-592). For this period, his political sensitivity can be described as Orléanist bourgeois. He was successively Sous-secrétaire d’État aux Finances from November 2, 1830 to March 13, 1831, Ministre de l’Intérieur (October 11, 1832) and Ministre de l’Agriculture et du Commerce (December 1832-April 1834), Ministre de l’Intérieur in April 1834, Président du Conseil et Ministre des Affaires étrangères in 1836 (February 22-September 6) and in 1840 (March 1) (Guiral P., 1986, p. 585-592). He left the government in 1840 and then joined the opposition. He was appointed Président du Conseil by Louis Philippe for barely a day on February 24, 1848 when the revolution broke out. Faced with his inability to restore order, he was dismissed by the King, who abdicated shortly after.

Following Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte's coup in December 1851, Thiers was forced into exile first in Germany then in Belgium, England, Germany again, Switzerland and Italy for a total of eight months ( Valance G., 2007 pp. 249-263). Opposed to the Second Empire, he lived in retirement from politics until 1862 and the publication of the last volume of his Histoire du Consulat et de l’Empire (Valance G., p. 269-270). He would be elected deputy of Paris in 1863.

The war of 1870 was an opportunity for Thiers to return to business, after the defeat of Sedan and the fall of the Empire, catastrophes which he had identified and tried to prevent. He was appointed “chef du pouvoir exécutif de la République française” after an electoral victory (Valance G., 2007, p. 316). The population, weary of war, saw in him the man capable of making peace. This was obtained at the cost of the crushing of the Commune which will remain the darkest stain in his political career. During this period, the mansion on Place Saint-Georges was destroyed by the Communards (Valance G., 2007, p. 340). The current mansion was rebuilt thanks to a state subsidy (Valance G., 2007, p. 358). Thiers, who had become Président de la République, then worked to collect the war indemnity of 5.5 billion francs negotiated with the Germans in exchange for their withdrawal from the regions they occupied. He would achieve this in less than two years by state loans which earned him the title of "liberator of the territory". Removed from power in 1873, he died in 1877. His funeral brought together millions of people (Valance G., 2007, fig. 38).

Creation of the collection

Adolphe Thiers had built an important but eclectic art collection. The exact chronology of its acquisitions still remains largely unknown. Research in sales catalogs and archives has made it possible to identify a few provenances and Charles Blanc's catalog gives some of them, but for most of the objects it is likely that their origin will remain unknown (L'or du Japan, 2010, pp. 93, 95, 123, 127, 162 and 163).

Concerning the Asian part, we just know from Charles Blanc (p. X) that Thiers began to build it “well before the expedition to China” so before 1860. The relationship between Thiers and art is old. From the start of his career, as a journalist, he commented on the salons (1822 and 1824) (Thiers A., 1822; Chauddonneret M.-C., 2005). Having become a minister, he launched several large commissions, several of which were attributed to Eugène Delacroix, of whom he was one of the defenders. He supported the renovation of the École des Beaux-Arts, for which he commissioned Félix Duban (1797-1870) in 1832 (Bonnet A., 1996). Thiers has a taste for art history and believed in the regeneration of artistic studies through the study of historical references and the old masters. Through his collection, he initially intended to bring together a panorama of the history of art. He bought a few originals, but gave them up for lack of money (Blanc C., 1884 pp. IV and VI). He also commissioned the painters of his time to copy the great works preserved in Italy. Thus his collection at the end of his life includes a set of 45 copies according to old masters. This will be the main cause of the discredit that the collection received after its donation to the Louvre. This discredit of Thiers' European collection largely explains the lack of interest of his Asian collection. Since his taste is considered bad in one area, it can only be bad in another.

The eclecticism of the collection probably also played into the negative perception as a whole. It indeed includes small séries of objects without thematic, stylistic or historical coherence in most cases and two rather long séries, European bronzes and Japanese lacquers. Egyptian and Greek antiquities counted 32 pieces, Renaissance terracottas 13, bronzes 93, marbles 13, ivories 15, carved wood 25, marquetry 5, "various sculptures" 11, cameos and intaglios 3, Venetian glass 11, copies from the great masters 45, paintings 5. On the Asian side, Chinese paintings consisted 17 pieces, Chinese and Japanese bronzes 15, cloisonné enamels 15, agates, jades, Lard stones 30, carved or inlaid woods 11, ivories 23, lacquers 65 and porcelains from China and Japan 36 pieces (Blanc C., 1884).

We will notice a few rare pieces from China and Japan alongside the hundreds of pieces from European manufactures in the porcelain collection, that were bequeathed by Madame Thiers. Unlike her husband, who mainly collected vases, she focused on serving porcelain, cups, plates, etc.

Legacy

Following Thiers' wishes, his collection was bequeathed after his death to the Louvre Museum (Blanc C., 1884, p. 283). The bequest was made by his widow Élise Dosne-Thiers who added her own porcelain collection to it, subject to the usufruct of her sister Félicie Dosne who, on her death, renounced the usufruct and decided to immediately deliver the completed bequest of his personal collection of snuffboxes. The Thiers bequest is therefore threefold.

Félicie Dosne added a condition to the bequest, that the objects all remain in the Louvre, not dispersed, in Thiers rooms. This explains why Asian objects from Thiers remained in the collections of the Louvre's objets d’art department during the thematic redistributions between national museums in the middle of the 20th century. The Thiers Foundation, moral heir to the Thiers bequest, subsequently accepted that certain minor pieces from the collection be placed in reserve and that important pieces, in painting, sculpture, decorative arts, be integrated into the other rooms of the museum where they could have been better positioned. Added to this are the conservation constraints of the graphic works in the collection, which cannot be exhibited permanently. Thus, the original structure of the Thiers collection is no longer seen together in the rooms of the Louvre, but the works and their legacy are shown as best as possible.

The entire bequest was cataloged by Charles Blanc in a book published in 1884 (Blanc C., 1884). The author comments on the whole collection and lists the objects that compose it. Charles Blanc had already briefly described it in the Gazette des Beaux-Arts in 1862 (Blanc C., 1862), this text having been republished in 1871 (Blanc C., 1871). The information in this catalog regarding Asia is of very limited use except in a few cases, because Blanc is unfamiliar with Asian art. The text also goes back and forth between notes relating to descriptive commentary in a sometimes grandiloquent and often apologetic style concerning the taste of Thiers. Others, yet les often, are well documented due to Blanc having had, on occasion useful sources such as a member of the Japanese embassy or information on the provenance of pieces. This reveals that Thiers collected in different ways. He received objects as gifts, for example from the Guignes family, who supplied several French ambassadors to China in the 18th and 19th centuries (Blanc C., 1884, p. XI). He also bought lone or group objects at public sales. Some come from very old collections such as the Denon collection (Blanc C., 1884, p. IX, 20 and 148). Several of his Japanese lacquers have a history dating back to the 18th century (L’or du Japon, 2010).

However, Thiers' collection continued to grow until the end of his with a few contemporary objects. He owned two cloisonné enamel vases that can be stylistically attributed to Japan in the 1870s (Paris, Musée du Louvre, inv. TH 313 and TH 314). Due to this we see that there is no logic to the Thiers collection, neither in terms of typological séries, nor in terms of technique or quality. It nevertheless conceals masterpieces or rarities of which, it seems, neither Thiers nor Charles Blanc were aware. Thiers cites some of the most mediocre quality objects in the collection as important pieces while ignoring that others are infinitely more important.

This is exemplified by the bottle inv. TH 457, which is one of the greatest masterpieces of Chinese famille rose porcelain bearing a poem and the mark of the Qianlong Emperor. The collection also includes one of the only cloisonné from the Yuan period known to date (inv. TH 310) or a cloisonné enamel brush pot also with the name of Qianlong (inv. TH 312) which is a masterpiece of this technique. The collection also includes a very important Indian jade cup inscribed with a poem by Emperor Qianlong. It belongs to a group of around a hundred jade and hard stone objects that entered the Chinese Imperial collections between 1760 and 1793 as tribal or diplomatic gifts. They aroused a real passion in the emperor who composed poems about the pieces which were later engraved on them (Xu X., 2015). The Thiers Cup is one of the only objects from this group that is not housed in the Palace Museum in Taipei or the Forbidden City in Beijing.

Related articles

Personne / personne

Collection / collection d'une personne