VARAT Charles (EN)

An inveterate traveller

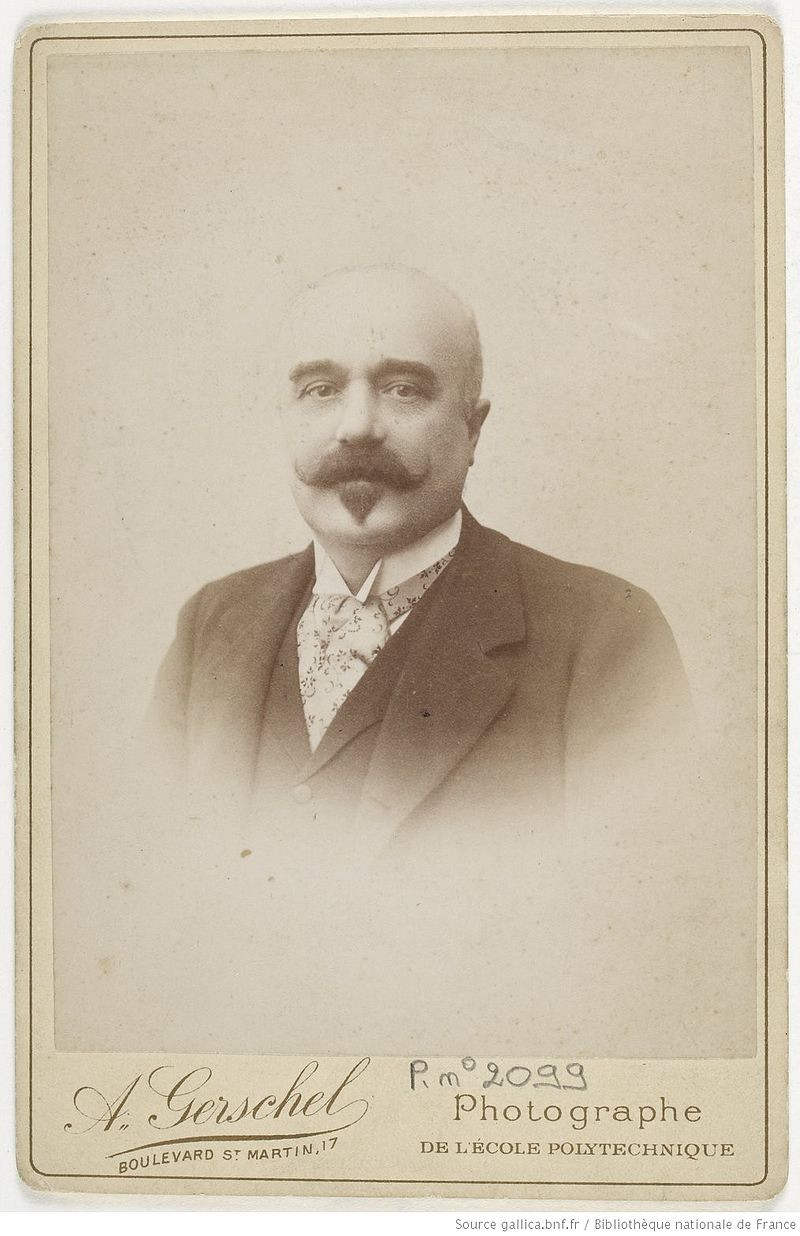

A rich Parisian industrialist, Charles Louis Varat (1842–1893) soon undertook many travels and explorations. In the context of a proliferation of ethnographic missions established by the Ministère de l’Instruction Publique et des Beaux-Arts—in context specific to the young Third Republic (1870–1940)—, and supported by a significant personal fortune, he became a professional ‘explorer’ and left France to travel around the different continents. At first, he travelled around France for leisure, and he then set off for Europe, America, North Africa, and finally Asia: his travels in India, Burma, Malaysia, Siam, Cambodia, Vietnam, China, Mongolia, Japon, Korea, and Russia all enriched and refined his knowledge of geography and ethnology. The Archives Nationales hold documentation, in particular relating to records of his expeditions in northern Russia and Siberia (1886), Korea (1888), and the Nordic countries (1891)—Holland, Sweden, and Finland. Appointed President of the Société Sinico-Japonaise in 1891, Charles Varat held conferences in the Société de Géographie as well as at the Congrès des Sociétés Savantes; he read out his thesis on L’Organisation Religieuse, Sociale et Administrative de la Corée (‘The religious, social, and administrative organisation of Korea’) in the Sorbonne in April 1893 (T’oung Pao, 1893, p. 311).

An expedition to Korea

Fascinated by Korea, Charles Varat informed the Ministère de l’Instruction Publique et des Beaux-Arts of his wish to explore the country’s farthest corner to satisfy his thirst for discovery. Consequently, the Ministry entrusted him with a scientific mission that consisted of compiling a collection to enrich, amongst others, the showcases of the Musée d’Ethnographie in the Trocadéro. Hence, after passing through Canada and California—from where he travelled to Japan—he then embarked for Vladivostok, and headed to Manchuria and Northern China. Varat disembarked in the Korean port of Chemulpo제물포, present-day Incheon인천, from the boat that came from Chefou芝罘, or Yantai烟台, in the Chinese province of Shandong 山東省(Broc, N., 1992, p. 432). It was via this port on the western coast, and during the month of October 1888, that Varat finally reached Seoul, where the Consul General of France, Victor Collin de Plancy (1853–1924), the French Republic’s chargé d’affaires in Seoul, warmly welcomed him and helped him to prepare for his expedition. Charles Varat stayed for fifteen days in the French legation in the capital, where he carefully observed both the inhabitants and urban life, and began to compile his collection by acquiring objects from local dealers. Collin de Plancy decided to assist him in his quest as an explorer: he provided him with bills of exchange and the necessary authorisations to successfully make his acquisitions, and he worked with dealers and interpreters who helped him assess the ethnographic and artistic characteristics of the proposed goods (Brouillet, S., 2015, p. 9).Without further ado, Charles Varat set off for the southern port of Busan부산via Daegu대구and Miryang밀양시. Leading a small caravan, he penetrated into the heart of this terra incognita, which he attempted to describe in great detail. In fact, he published an account of his long journey almost four years later in the journal Tour du Monde, published in five parts between 7 May and 4 June 1892, foreshadowing a larger work that was due to be published by Éditions Hachette, but which was inadvertently cut short by his sudden death in Paris on 22 April 1893 (Varat, C., 1892, pp. 289–368). This work was intended to show the ‘results of his explorations’, snippets of which Charles Varat had already revealed in his Parisian conferences. Having reached Busan, at the end of his journey, Charles Varat returned to China and then France, after travelling through Indochina, Siam, and India; his sojourn in Korea had lasted, all in all, barely one and a half months.

An eclectic and exhaustive exhibition

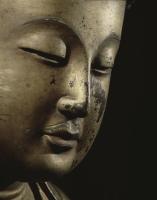

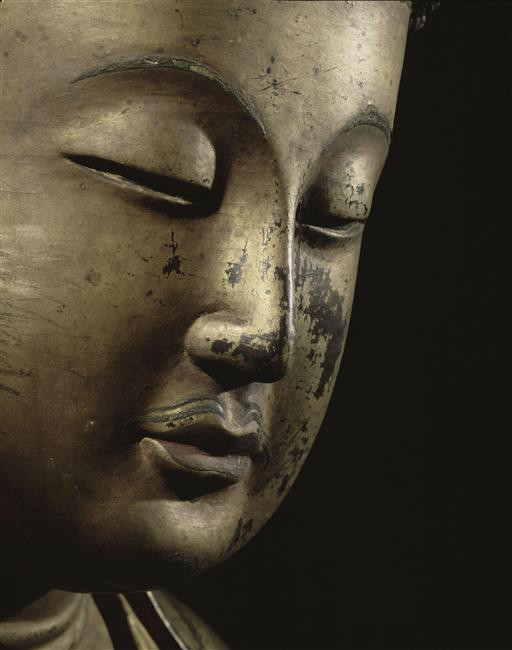

In December 1888, Charles Varat informed the Ministère de l’Instruction Publique that he was shipping fifteen crates ‘containing part of the ethnographic collection [that he had] assembled during [his] mission in Korea’ (AN, F/17/3012/1). Once the objects had been delivered, concurrently with the 1889 Exposition Universelle held in Paris, they were shown to the general public at the Palais du Trocadéro, and presented in an educational and attractive way by the explorer. According to a note drafted in the 1892 Tour du Monde, this immense collection, donated to the French State by Charles Varat, comprised ‘almost two thousand articles’ (Varat, C., 1892, p. 354). Although no list has survived of all the objects compiled by Charles Varat during his many travels, there is nevertheless a volume of photographs dating from 1889 held in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, which shed light on the way in which the collection was arranged in the Trocadéro. In addition, the collection was recorded in an inventory drawn up by the Musée Guimet in 1910, which listed some 335 articles, complemented by rare objects that Charles Varat mentioned in his Voyage en Corée. Many admired the extremely composite aspects of this vast collection, which included objects that attested to Korean craftsmanship dating from the Goryeo period 고 —시(918–1392) and the Joseon period 조 —시(1392–1910): ceramics, bronzes, and woodcarvings; it also comprised objects that illustrated more generally a Korean culture and identity—Buddhist and Shamanic costumes and masks, furniture and paintings of auspicious value, very different from the refined aesthetics specific to the court painting of scholarly officials (Brouillet, S., 2015, p. 118; Cambon P., 2015, p. 63). While the collection is more linked with ethnography than the fine arts, certain objects stand out due to their great artistic finesse; worthy of mention are the statue of Avalokitesvara à mille bras et aux mille yeux (‘Thousand-arms, Thousand-eyes Avalokiteśvara’), a truly exceptional object made from cast iron during the Goryeo dynasty and which came from the Temple of Tongbang-sa통방(MNAAG, inv. no. 15369), and the gilt bronze Bodhisattva assis sur un lotus (‘Bodhisattva sitting on a lotus’), also dating from the Goryeo period (MNAAG, inv. no. 15258). These are complemented by remarkably large collections of objects, such as the series of 170 miniatures by the painter of genre scenes Kim Chun-gun 김준근, called Kisan 기산, dating from the nineteenth century, and the collection of painted wooden masks, with their grimacing profiles, traditionally worn during popular dances and masked theatre plays, a custom deeply rooted in eighteenth-century Korean folklore.

The 1889 Korean exhibition

It was on the afternoon of 18 September 1889 that the ‘Exposition Coréenne’ was inaugurated; after returning from his latest expedition, Charles Varat held the event in the Palais du Trocadéro’s exhibition gallery, arousing the curiosity of the Parisian public. In the midst of a mass of ‘exotic’ objects, the exhibition presented in an educational way and via various ethnographic reconstitutions, the everyday life of the country that Westerners called at the time the ‘Land of the Morning Calm’ (Chaillé-Long-Bey C., 1894), or the ‘Hermit kingdom’, a land that Europeans were relatively unfamiliar with until that point. This highly ambitious project provided a comprehensive overview of Korean culture dating from the end of the Joseon period (1392–1910), by presenting to a neophyte public a multitude of ethnographic objects of all kinds, brought together in a vast eclectic collection ‘connected with the arts, sciences, agriculture, industry, and commerce’ (Le Monde Illustré, 1890, p. 106). The event was immediately covered and relayed by the contemporary press, which highlighted the favourable reception of the exhibition, and its great success with regard to the number of visitors and revenues generated.

The attribution of the collection to the Musée Guimet

Once the temporary exhibition came to an end, in December 1889, Charles Varat expressed a wish to prolong the presentation of his collection to enable the general public to have permanent access to it. Determined to find a museum that had enough rooms to exhibit such a large collection of objects, he used the article published in Le Monde Illustré on 15 February 1890 to enhance the multifaceted characteristics of his collection, whose finest objects were highlighted by engravings created from photographs taken during the exhibition. Emphasising the significant interest of the Varat Collection ‘from the perspective of the History of Religions’ (MNAAG archives, ‘Charles Varat’ file, (inv. no. unknown)), the Ministère de l’Instruction Publique et des Beaux-Arts attributed it to the recently created Musée Guimet—which opened in 1889, on the corner of the Avenue d’Iéna and the Rue Boissière—, where the objects were transferred in 1891. In the Musée Guimet, the collection was entrusted to the care of the Korean aristocrat Hong Jong-u (1851–1913), assigned to the Musée by Émile Guimet, on the recommendation of Félix Régamey (1844–1907) as a ‘foreign collaborator’ for one year. He and Charles Varat worked together on classifying and drawing up an inventory of the collection, in order to arrange it in the museum’s rooms and write the object descriptions—written in French and translated into Hangeul한—with French transcriptions. For two years, the gallery of the ‘Korean religion and ethnography’ (Musée National des Arts Asiatiques – Guimet, 1996, p. 202) gradually took shape and was eventually inaugurated on 11 April 1893, on the second floor of the museum, where it occupied seven rooms, providing a curious Parisian public with an exhaustive ethnographic overview of Korea via the Varat, Collin de Plancy, and Steenackers collections—the latter collections came from transfers and donations that aimed to complement the ensemble compiled by Varat. The arrangement of the mannequins and objects was largely based on the layout of the Trocadéro exhibition, using a method that set out to reconstitute, amongst others, the various spheres that structured life in Korea: the exhibited figures embodied all the ages and stages of life, from childhood and marriage to funerals, using a clever mixture of objects complemented by a decidedly ethnological approach.

The dispersion of the Varat Collection

In 1895, the transfer—based on a decision taken by the French Ministry of Public Instruction—of the Korean weapons that featured in the Varat Collection to the Musée de l’Armée opened the way for the dispersion of this vast ensemble, which had gradually expanded over several years as a result of various permanent loans. Indeed, no longer able to exhibit or conserve the entire collection—and focusing more on works relating to archaeology and the fine arts—, the Musée Guimet began a policy of transferring objects it considered of lesser interest, and which it entrusted, amongst others, to provincial ethnographic museums. Hence, a large portion of this vast ensemble was broken up as a result of permanent loans made to the museums of Bordeaux (1904), Le Havre (1915), and the Trocadéro (1930, 1943, and 1962), which explains the collection’s current dispersion.

Related articles

Personne / personne

Collection / collection d'une personne