LEFÈVRE Camille (EN)

Biographical article

Camille Lefèvre (1853–1933) showed an early talent for and interest in drawing and painting. After his apprenticeship with a woodcarver, he moved to Paris at the age of seventeen where he attended courses at the École des Arts Décoratifs. In 1872, he enrolled at the École des Beaux-Arts in the studio run by the sculptors Pierre-Jules Cavelier (1814–1894) and Aimé Millet (1819–1891). Here, he received a classical training inspired by antiquity and neoclassicism. The diplomas held in the Musée d’Art et d’Histoire in Belfort (MAHB, unknown) indicate that, under these teachers’ guidance and tutelage, he won the Second Grand Prix de Sculpture twice (1877 and 1878), as well as the Grande Médaille d’Émulation awarded by the École des Beaux-Arts (1877), but not the Grand Prix de Rome, the only recognition that could ensure commissions. He was awarded a third-class medal in the sculpture section at the 1994 Salon (MAHB, unknown), a second-class medal in the same section in 1888 (Catalogue Général Officiel de l’Exposition Universelle de 1889,1889, p. 86), and a silver medal in the sculpture section at the 1889 Exposition Universelle (MAHB, unknown). He is cited in a diploma dating to 1884 as a being a professor at the École de Dessin et de Modelage de la Chambre Syndicale de la Bijouterie in Paris, then in 1908 as professor at the École des Arts Décoratifs (MAHB, unknown).

At the same time, his works show that he sought major commissions—whether public or private—, and that he took part in contests to erect commemorative monuments that were run by municipalities (Guibert, C., 2003). The Third Republic pursued the major urbanisation work launched during the Second Empire and public buildings were adorned with sculptures, providing statue sculptors with numerous projects. Hence, Camille Lefèvre created two statues for the monument dedicated to the victims of the 1871 Siege of Paris (1879), the fronton of the headquarters of the Crédit Lyonnais (1881), the Guéstatue(a great success at the 1884 Salon) bought by the Mairie of Paris, and the decorative elements on the façades of the mairies of Ivry-sur-Seine and Issy-les-Moulineaux (1896).

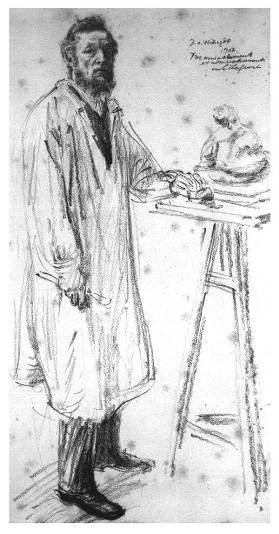

Portraits of friends

The friendship and support of Eugène Carrière (1849–1906), whose paintings are similar in many ways to the work of Lefèvre (Guibert, C., 2003, pp. 19–21), enabled him perhaps to attract the attention of public patrons. He also benefited from the support of Rodin (1840–1917): although nothing in the Musée Rodin archives confirms that Lefèvre was employed by Rodin as a practician, in contrast with the claims made by Guibert Caroline (2003), the correspondence the master received shows that the latter supported Lefèvre in many endeavours, whether it involved providing works for the raffles at Madame Lefvre’s Orphelinat des Arts in Sant-Ay (Loiret) or backing Camille Lefèvre’s attempts to obtain commissions from the French State (MR, file: LEF 3745) or a medal (MR, file: Fagel).

His friends and family often posed for portraits, a practice that was very common at the time: hence, Lefèvre created the portraits of Jules Lermina (bronze, CLS. 54), Marie Howet (bronze, CLS. 55), and Lisbeth Carrière (stone, CLS. 44), while executing commissions from private individuals in plaster, bronze, and stone (Guibert, C., 2003, pp. 22–24). An heir to the eclecticism that predominated throughout the second half of the nineteenth century, Camille Lefèvre did not restrict himself to a particular style and adopted a variety of approaches, ranging from bas-relief profiles to busts en ronde-bosse, in a realistic and vigorous style imbued with humanity and sensitivity.

Art Nouveau at the core of his decorative principles

In the field of the decorative arts, Camille Lefèvre’s oeuvre is typically Art Nouveau in style, in which figures and ornamentation are dominated by supple and decorative lines. It is significant, as pointed out by Nicolas Surlapierre (2014) with regard to the Sculpteur of the main façade of the Mairie of Ivry (in situ; plaster model in Belfort: CLS. 101) that Lefèvre selected the image of an artist working on floral decorations to represent an allegory of his métier. In line with the partisans of Art Nouveau, he was very interested in the idea of art in everything, and contributed to the rehabilitation of domestic objects that enriched the intimate decorations of everyday life. The collection he donatedto the Musée d’Art et d’Histoire de Belfort includes many models of crockery, vases, furniture, and fireplaces, demonstrating that right to the end he had a passion for the decorative arts and a taste for the decompartmentalisation of genres.

In fact, decorative sculpture played a very important role in Lefèvre’s career at the turn of the twentieth century. The collection of sketches donated by Camille Lefèvre to the Musée d’Art et d’Histoire de Belfort reflected the artist’s interest in floral motifs, applied to models of consoles and ceramic tiles. Although Lefèvre’s role is unclear, he seemed to participate in the decoration of the shop window of Siegfried Bing (1838–1905), located on the Rue de Provence in Paris (Guibert, C., 2003, p. 110); more certain, however, was his contribution to decorating the façades of various Parisian buildings (50, Rue du Rocher, in the 8th arrondissement; 15–21, Boulevard Lannes; and 12, Rue Puvis-de-Chavannes, in the 17th arrondissement), of which certain models held in the Musée d’Art et d’Histoire de Belfort attest to his ability to adapt natural motifs to the architecture of buildings.

A consecrated … then forgotten artist

The 1900 Exposition Universelle marked a major step in his dual career as a sculptor and decorator. The Musée de Belfort archives provide a record of the many diplomas he was awarded: a silver medal as a representative of the Chambre Syndicale de la Bijouterie in the category ‘Enseignement spécial industriel et commercial’; a member of the admissions committee for ‘Joaillerie et bijouterie’; a gold medal in ‘Medal sculpture and engraving’; a Grand Prix for ‘Décoration fixe des édifices publics et des habitations’ for the Maison Poussielgue-Rusand; and a gold medal in ‘Céramique’ for the Maison Alfred Hache. He was awarded a Légion d’Honneur in 1901 (MAHB, unknown), and he also achieved a certain international recognition: he was acknowledged as a partner by the Société des Artists Hongrois in 1901, and awarded a silver medal at the 1908 Exposition Franco-Anglaise (MAHB, unknown). He was a professor at the École Nationale des Arts Décoratifs as of 1903, had his own studio between 1910 and 1918, and was one of the founding members of the Salon d’Automne in 1903, of which he was Vice-President until his death (Guibert, C, 2003, pp. 58–59). This marked the high point in his career. He became a major figure of the institutional landscape, but his creative work gradually subsided. Thanks to his collaboration with the architect Adolphe Dervaux (1871–1945), he decorated the railway stations of Biarritz (1907) and Rouen (1928), along with various funeral monuments (Vaucresson, Saint-Ay, and the Rouché monument, for example), and created interior decorations.

While the choice of certain themes linked to the world of labour (Débardeur invectivant, pencil on paper, CLD. 29) and street scenes (Dans la Rue, work destroyed), as well as certain attempts to prioritise a sensitive approach, in particular,in Le Remords (plaster, CLS. 41), which can be likened to the realistic work by Aimé Jules Dalou (1838–1902), the facture remained classical: soft and tender, and never really freeing itself from his initial training. Influenced by realism, Lefèvre achieved some success thanks to several works (Le Bonheur>/i>, marble, thermal baths of Aix-les-Bains), which were subsequently forgotten. Hence, certain commentators referred to an artist ‘torn between his classical education and the most modern of approaches that his will rather than his temperament led him to explore’ (Vitry, P., 1910, p. 64). Although he was still a member of the Salon d’Automne, his fame rapidly declined, and he only rarely featured in the Salon’s reports after the Great War; and his death in 1933 was treated with indifference (Guibert, C., 2003).

A collection, a life

Given the Belfort origins of Marie Richon (1849– ?), whom Lefèvre married in 1882, her role as a voluntary nurse during the siege of the city in 1870–1871, and to avoid dispersion in auction houses, the couple decided in 1932 to donate the artist’s entire collection and the contents of his studio to the City of Belfort. In addition to the above-mentioned reasons, the notarial documents of the donation with reservation of the usufruct granted on 8 July 1932 (AMDB, 2L20) stipulated that the Musée should create a room in the building called ‘Monsieur et Madame Camille Lefèvre’ to house all the donated objects for fifty years, with the exclusion of any other works. The way in which the collection was compiled by the Lefèvre couple is not documented, but the desire to ensure it would not be dispersed attests to the fact that both of them were sincerely attached to it, proving perhaps that the various articles were given by or bought from friends, or that they reflected theexistence of a deliberately aesthetic approach.

This donation included all the works from a studio (sculptures and studies, both modelled and drawn), as well as a private collection comprising works acquired from his artist friends. Numerically, it included the decorative arts (90 articles, mostly ceramics by Émile Lenoble, 1875–1940), watercolours and pastels (27 articles, including several by Marie Howet, 1897–1984, and Armand Guillaumin, 1841–1927), drawings (more than 1,018 articles, in particular, from his studio, as well as works by Armand Berton, 1854–1917; Henry Lerolle, 1848–1929; Eugène Carrière and Théophile Steinlen, 1859–1923), Japanese prints (112 articles), engravings (87 articles, by Armand Berton and Auguste Danse, 1829–1929; Albrecht Dürer, 1471–1528; and Rembrandt, 1606–1669), lithographs (293 articles: Carrière and Paul Gavarni, 1804–1866, and Maximilien Luce, 1858–1941; Steinlen and Adolphe Willette, 1857–1926; Charles Émile Wattier, 1800–1868; David d’Angers, 1788–1856), paintings (44 articles: Paul Baignères, 1869–1945; Berton, Guillaumin, Howet, Lerolle, and Luce), moulds (65 articles: medals from the Italian Renaissance and Gothic objects), sculptures (28 articles, including works by Jules Dalou, Rodin, and Albert Marque, 1872–1939), books (70 articles), and several posters, coins, and medals.

It is particularly important to note, with regard to the collection of such a sculptor, that the artist was interested in the work of one of his forerunners, David d’Angers: although the collection includes no three-dimensional pieces, it does contain almost 100 lithographs that reproduce the busts, medals, portraits, and monuments executed by the Angers-born artist. The Belfort Collection also concerns a large range of three-dimensional works created by Lefèvre, which highlight his favourite themes (allegories, portraits, intimate scenes, and decorative architectural work). These works also make it possible to grasp all the stages required to create a statue, from the rough clay model to the final work in bronze or stone. The other noteworthy fact is that the sculptor worked hard on perfecting his drawing skills and left behind a great many works: portraits, preparatory studies for his sculptures that attest to his quest for the most appropriate posture and the most balanced composition, projects for domestic objects in the Art Nouveau style, and sketches of animals, landscapes, and anatomy.

His private collection, in the field of painting, prints, and sculpture, attests both to his artistic tastes and friendships. Camille Lefèvre managed to surround himself with many artists and literary men who supported him and sometimes used their influence to obtain commissions for him, for example Jules Lermina (1839–1915) and Léon Fagel (1851–1913), eponymous files in the Musée Rodin). His studio at 55, Rue du Cherche-Midi in Paris was open on the second and fourth Thursdays of each month from 1 January to 1 June, as attested by one of Madame Lefèvre’s calling cards (MR, LEF 3745), and it is perhaps not astonishing, consequently, that he was Vice-President of the Salon d’Automne for many years. Ever faithful to his friends, Camille Lefèvre even devoted part of his career to completing Dalou’s unfinished works, such as the Panhard Levassor monument at Porte Maillot in Paris (1903, in situ) and the monument dedicated to Gambetta in Bordeaux (Musée d’Aquitaine, 1905), but he denied that he was a follower: ‘When I had to continue the work interrupted by his death, I tried to continue in his spirit. In doing so, I was simply acting as a good friend and it would be unfair to say that I had adopted his aesthetic approach’, he wrote in a letter published by the journal Art et Décoration in April 1928.

An interest in the Far-Eastern arts

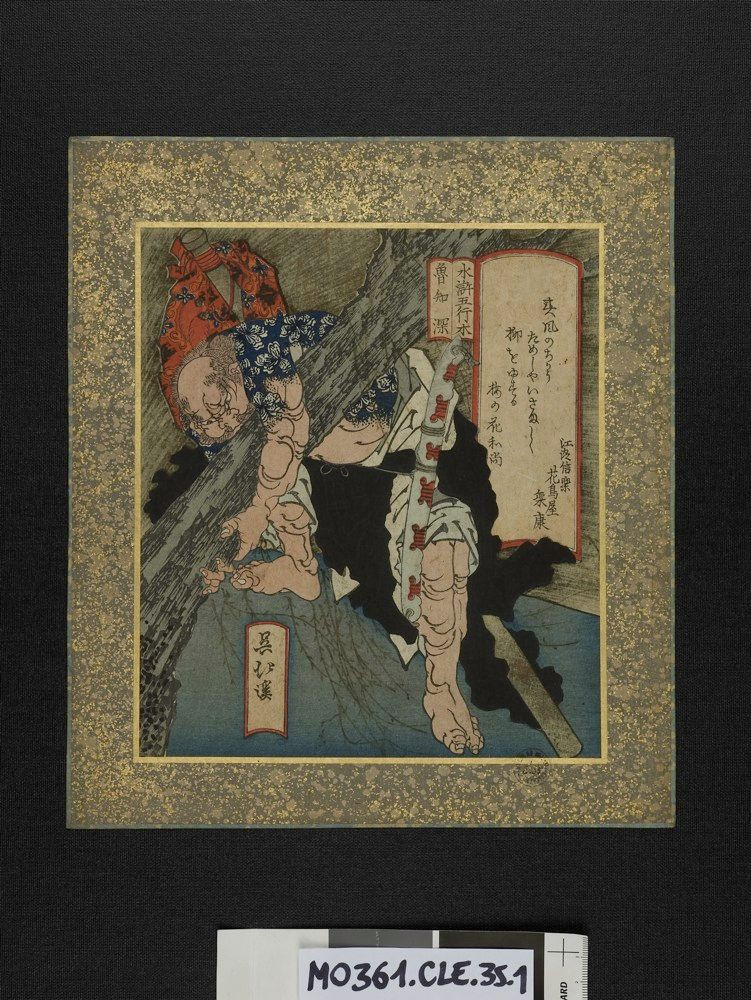

Thanks to Camille Lefèvre’s donation, the Musée d’Art et d’Histoire in Belfort has a collection of 112 Japanese prints. They are divided into several categories, in particular, landscapes, Kabuki scenes, and portraits of actors, and lastly, those of beautiful people (bijin-ga). The vast majority of the works were attributed, and the authors of these prints were amongst the most famous artists, for example fourteen pieces by Katsushika Hokusai 葛飾北斎 (1760–1849), thirteen by Utagawa Toyokuni歌川豊国 (1769–1825, and his heir Kunisada 歌川国貞, 1786–1864), twelve by Kikukawa Eizan 菊川英山 (1787–1867), six by Totoya Hokkei 魚屋北渓 (1780–1850), three by Utagawa Kuniyoshi 歌川国芳 (1797–1861, for example the Vingt-quatre Parangons de la piété filiale, CLE.2), and three by Andō Hiroshige 歌川広重 (1797–1858, in particular, the Cent Vues célèbres d’Edo, CLE.109). Amongst the most important articles, Lefèvre acquired nine of Hokusai’s Mangas—sketchbooks comprising landscapes, representations of Japanese fauna and flora, and images of daily life and imaginary worlds (CLE. 97-CLE. 103, CLE. 105 and CLE. 110).

Unfortunately, Camille Lefèvre did not reveal anything about the origin of his collection, or what he used it for. The library he bequeathed did provide come clues about the way in which it was documented. Hence, three major catalogues were highlighted: that of the sale of the Hayashi Collection (two volumes, 1903), that of the sale of the Charles Gillot Collection (1904), and that of the exhibition of Japanese engraving held in 1890 at the École des Beaux-Arts. Incidentally, Lefèvre owned the works of Ernest Francisco Fenollosa (1853–1908) (L’Art en Chine et au Japon, 1913) and Maurice Paléologue (1859–1944) (L’Art Chinois, 1910). He also seems to have had a particular use for the Hayashi catalogues, as he added the handwritten indications of the page numbers of the illustrations in the Index: while we have been unable to investigate the means by which these prints were acquired due to a lack of time, it is certain that sale catalogues provided Camille Lefèvre with a repertoire of images, as he used books as tools for his iconographic research.

However, these hypotheses are tenuous and the only scientific study conducted to this day about this artist suffered from a lack of archive material (Guibert, C., 2003, p. 74). Unfortunately, the donation did not include archive documents and the few surviving letters do not address this aspect, in particular, the correspondence with Rodin held in the Musée Rodin. To confirm frequent professional use, a comparison needs to be made within the collection, between these prints and a vast ensemble of documents (which have not been inventoried) that bring together Lefèvre’s tracings and various press cuttings, and extracts of specialised journals he collected, for example the ‘Modèles inédits’ in the journal Arts Modernes published by Alfred Nicolas Jeune, La Décoration, and Revue de la Famille. In both fields, it is worth noting that Lefèvre was particularly interested in a very Japanese style of decorations, and he collected and traced images representing carefully observed waterlilies, flowering cherry tree branches, long serpentiform or arabesque stems, and variegated birds in natural settings. Attesting to his interest in oriental art, he also tried to place a spectacular dragon in a half-moon, in an oriental layout.

The general themes present in the collection of prints were linked to Camille Lefèvre’s centres of interest. Japanese landscapes, often linked to the ‘mountain and water’ motif, are associated with several pictures by Maximilien Luce (Landscape, CLD. 887) and Armand Guillaumin (Les Roches Rouges d’Agay, CLA. 15; Paysage, CLP. 10) in the collection, and the latter attests to the fact that Lefèvre himself, a painter and occasional draughtsman, also liked this maritime theme (Pins Maritimes, CLD. 677; Arcis-sur-Cure, CLD. 671). It is also important to note that the sumptuousness of the clothing of the courtesans or Kabuki actors matched the artist’s decorative tastes: complex or floral motifs are everywhere in these prints and perfectly matched the desire for formal renewal that characterised the epoch. Lastly, Hokusai’s Manga, with their multiples models of insects, animals, and flowers, were in the same category of sources of inspiration for the creation of novel works. It is therefore highly likely that Camille Lefèvre, prompted by his curiosity for the decorative arts, took an interest in Japanese art with the aim of compiling a collection of models that could be used for his own artistic work.

Related articles

Collection / collection d'une personne

Personne / personne