CHARPENTIER Georges (EN)

Biographical Article

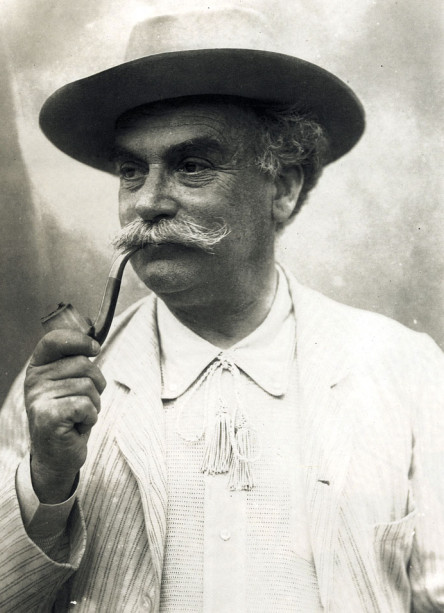

Georges Charpentier (1846-1905) was a publisher with an artistic and scholarly temperament, and was a close friend of Émile Zola (1840-1902). He was a patron of the Impressionists, a regular at premieres and salons, and he took over the family publishing house from his father Gervais Charpentier (1805-1871) in 1871, eventually selling it to his partner Eugène Fasquelle in 1896 (Serrepuy-Meyer V., 2005).

The publisher wielded a secret weapon that conferred upon him an indisputable prestige: the salon of his wife Marguerite Charpentier (1848-1904). There, a diverse range of artists and authors would rub shoulders with leaders of the republican party and Parisian society. From the literary evenings of the early 1870s around Flaubert to the meetings of the Dreyfusards, the Salon Charpentier was an essential part of Parisian social life (Meyer V., 2009; Meyer V., 2020).

Wikimedia Commons.

Surrounded by Japanese Objects

The Charpentiers were collectors and their passions were expressed in two complementary realms: Japanese art and Impressionist painting. The novelist Abel Hermant (1862-1950), who would become their son-in-law, describes his first evening spent with them, shortly after his entry into the publishing house's catalogue in 1887, offering us a view of their hôtel particulier in the rue de Grenelle: "In my publisher's salon I perceived, almost simultaneously withits bourgeois nature, another, no less unexpected: from the front door, one would have believed oneself at a painter’s home. First, at the bottom of the stairs […] was samurai armour. Then, all over to the right of the stairs […], their frames touching: drawings, watercolours, prints. Other frames and kakemonos decorated the gallery. The first room one entered from the gallery was the dining room, where a true exhibition of paintings began, with place of honour given to one of Claude Monet's most famous paintings, Les Glaçons.” (Hermant A., 1935, p. 126)

The tastes of the time were characterised by abundance: a cultivated mix, with allobjects providing a pretext for ornament, arranged in apparent accumulative disorder. A profusion of objects and paintings contributed to the rooms’ sophistication. An invitation card designed by Georges Jeanniot (Paris, musée Carnavalet) for the Salon Charpentier allows us to imagine an interior characterised by this abundance of styles: on the right we see a bronze or an antique sculpture, while the fireplace bears objects of Japanese inspiration and the top of the window appears to be ornate in the neo-18th century manner. Japanese objects are only one element of the decoration, but they take a preponderant place at the Charpentiers’ home.

This taste for Japanese objects was confirmed by Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919), whose remarkswere reported by Ambroise Vollard (1866-1939): "The reception rooms were entirely decorated with Japanese items, according to the fashion of the time” (Vollard A., 1938, p. 196). (Is a hint of irony regarding the phenomenon of fashion to be detected in the painter's words?)

The Charpentiers were close to the first collectors of Japanese art and did not fail to take inspiration from them in introducing Japanese objects into their decorative schemes. To furnish their new interiors on the rue de Grenelle, Marguerite called upon Philippe Burty (1830-1890), the collector and historian of Japanese art. On November 1, 1875, he gave him this advice: "Dear Madam, I am very proud that you thought of me regarding the Japanese apartment that you are contemplating. […]. You know better than I that the Japanese constantly stand on their knees, that the Japanese sit, without intermediary, on mats. It's too scant for us. But you could boldly take on the sofa system, with cushions as armrests. All in all, it's very practical. We could do a lot with a few dresses unstitched and resized as needed. […] Edmond de Goncourt has just made a ceiling with an actor's costume. It’s wonderful. You can steal his idea. He is quite myopic. […] For the walls, we would frame in an antique red [?] some of these paper scrolls with drawings and watercolours, which are true paintings, with flowers, birds, … Here, as a guest, are a few notes. Your Parisian instinct will tell you much more than my engravings which I will lend you” (Burty, 1875). Two days later, Edmond de Goncourt (1822-1896) in turn offered his services to the publisher: “I learned from Burty, my son in Japanesery, that Madame Charpentier was making a Japanese boudoir; if she wanted to see two rooms furnished in this style, I would be at her disposal.” (Goncourt, 1875) However, the tone quickly becomes more ironic. In his Journal, he notes on November 24, 1876: "Here is Madame Charpentier who is getting into Japanesery and buying elephants! (Goncourt, 1989).

The Charpentiers were also among the earliest patrons of the Impressionists, particularly of Pierre-Auguste Renoir. From the mid-1870s, they sought to help him by placing several orders for portraits and landscapes. Two of his works figure prominently in the Charpentier house, a pair of wall panels embellishing the staircase and a portrait ofMadame Charpentier et ses enfants, which parallel the role of Japanese art in their lives.

In 1876, they commissioned painted panels from Renoir to decorate the stairwell of their hôtel particulier (demolished in 1926). Thesebecame part of the Otto Gerstenberg collection (1848-1935) in Berlin and were seized by Soviet troops, which explains their current presence at the Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg (Adriani G., 1999, p. 38). Presumably, Renoir's aim was to render the atmosphere of the interior and to evoke the masters of the house welcoming their guests, without however seeking an exact likeness. Edmond Renoir (1849-1944), the painter's brother, posed for the male figure and Marguerite Legrand (?-1879), Renoir's main model at that time, for his female counterpart. This stand-in for Marguerite Charpentier holds a Japanese fan. Indeed, her enthusiasm for Japanese art would be partly at the origin of her interest in the Impressionists. The painter had already used the Japanese fan as an accessory in Nature morte au bouquet in 1871 (Houston, The Museum of Fine Arts, inv. 51.7). The object plays an important role here in unifying the different elements, echoing the outline of the figure and the arabesques of the ramp, which recall the linear motifs of Japanese prints.

Three years later, it was no longer simply accessories, but the entire decor that reflected the Charpentiers’ Japanese taste. The Madame Charpentier et ses enfants was made in 1878 and exhibited at the Salon of 1879. The Japanese furnishings forming the canvas’ background (screens, kakemono) was the subject of very thorough analyses in the book by Colin B. Bailey devoted to portraits of Renoir (Bailey, Colin B., 1997). Michel Robida affirms that kakemonos decorated with falcons alternated with strips of cherry silk that had originated from Marguerite's parents' home on the place Vendôme, and had been the summer curtains in the living room of her grandmother, Isabelle Lemonnier (Robida M., 1958, p. 10). According to Théodore de Banville (1823-1891), the scene takes place in a small salon that served as a smoking room, a "little Japanese salon, where amusing trinkets burst here and there their notes of vermilion and gold" (Banville T. de, 1879). Philippe Burty, meanwhile, locates the portrait between the "amusing walls of an ornate Japanese-style boudoir" (Burty P., 1879).

Samurai armour, kakemonos, fans... contemporary sources, whether literary or artistic, clearly show a family living in a Japanese setting in the 1870s. These few testimonies remind us that the Charpentiers were close to the first “discoverers" of Japanese culture in France and that their action would largely contribute to the dissemination of this art and this culture in the years 1870-1890.

Supporting the Dissemination of Japanese Art in France

“Before 1870, Japanese art, was not unknown in France, but its works were still rare there and only appeared in the collections of a few aficionados; the public was not familiar with them, so to speak. The popularisation of Japanese art does not reach beyond 1873, and this art brought something new to the West.” Thus is the arrival of Japanese art in the West in the 1920s described by Georges Rivière (1855-1943) (Rivière G., 1921, p. 57). According to Albert Boime (1933-?), it was businessmen who were responsible for a fashion that proved an awakening for French artists. Antique dealers, ceramics manufacturers, and department stores established links that allowed creative minds to make contact with Japanese art (Boime A., 1979, p. 65). On the contrary, according to Ernest Chesneau (1833-1890), "it is actually through our painters that the taste for Japanese art took root in Paris, was communicated to art aficionados and people of the world, and consequently imposed upon the industries of art” (Chesneau E., 1878). In either case, thanks to his connections in the artistic world, Georges Charpentier was in an ideal position to discover and support this movement, in particular through the works in his catalogue.

Japanese art began to find an audience in France from the 1860s into the 1870s. The Goncourt brothers and Philippe Burty began their collection in the 1860s; in the background of the portrait of Émile Zola by Édouard Manet (1832-1883) painted in 1868, works of Japanese art are visible. The 1867 Universal Exhibition in Paris presented thousands of objects for Japan's first participation in an international exhibition. In 1872, Philipe Burty offered a first definition of Japonisme in a series of articles published in La Renaissance littéraire et artistique from May 18, 1872 to February 8, 1873 (Basch S., 2021). In 1874, the critic Jules Claretie (1840-1913) mocked this new fashion in a work of criticism published by Charpentier: "Our Japanese Parisians […] hope that the study of trinkets from the blue countries will give them a color and a vein of new inspirations. This imitation of an art that is obviously very intriguing and very seductive is a disease, but it’s good to leave this art to the realm of intrigue; it is a fever whose first symptoms are now appearing and which, as I fear evermore, will increase. It has already been baptised with a name: Japonisme. […] Japonisme is, moreover more than a fantasy; it is a passion, a religion […]. Most of these artists […] know little about the art […] of Japan except through a few albums brought back by travellers, or through a few trinkets bought on rue Vivienne” (Claretie J., 1874, p. 272). The same article is nevertheless enthusiastic about the Cernuschi exhibition of bronzes and ceramics at the Palais de l'Industrie, this collection being the result of the trip to Asia by Henri Cernuschi (1821-1896) and Théodore Duret (1838-1927) between 1871 and 1873.

In 1874, the Charpentiers were at the heart of this Japanese vogue. On March 11, 1874, in their living room on the Quai du Louvre, the Japanese comedy La Belle Saïnara by Ernest d’Hervilly was performed. Even the invitation card was Japanese-inspired: a bamboo stalk, birds, and the silhouette of a woman in traditional costume, accompanied by Japanese characters. In March 1874, Flaubert thanked Marguerite for her "Japanese placard", in connection with his play Le Candidat, the premiere of which was postponed: “It was with great difficulty that I could get you a box.” (R. Descharmes, 1911, p. 631).

In 1876, it was Émile Guimet's turn to leave for Asia to study the religions of the Far East. In 1878, he published his Promenades japonaises illustrated by Félix Régamey (1844-1907) with Charpentier.

Enthusiasm was at its peak at the 1878 Universal Exhibition in Paris. In his article entitled "Japan in Paris", Ernest Chesneau describes the fever seizing collectors: "Enthusiasm spread to all the workshops with the speed of a flame running on a trail of powder. […] We kept abreast of new arrivals. Old ivories, cloisonné enamels, earthenware and porcelain, bronzes, lacquers, carved wood, brocaded fabrics, embroidered satins, albums, books with engravings, and toys no more than entered the merchant's shop before immediately entering artists' studios and the cabinets of men of letters. Thus, these beautiful and rapid collections were formed from this already distant date until the present moment. […] It is no longer a fad, it is infatuation, it is madness.” He cites the following names, including Charpentier and some of his relatives: the painters Édouard Manet, James Tissot (1836-1902), Henri Fantin-Latour (1836-1904), Carolus Duran (1837-1917), Claude Monet (1840-1926); the engravers Félix Bracquemond (1833-1914) and Jules Jacquemart (1837-1880); the writers Edmond and Jules de Goncourt, Champfleury (1821-1889), Philippe Burty, Émile Zola; the travellers Henri Cernuschi, Théodore Duret, Émile Guimet, and Félix Régamey. He lists the customers of the La Porte chinoise shop, located at 220, rue de Rivoli and run by Émile and Louise Desoye, a meeting place for the first Japonisants, including Georges Charpentier.

The publisher lent objects to the great Japanese exhibition hosted by the Trocadéro from May to November 1878. During the Universal Exhibition, he organised a demonstration of the Japanese watercolour technique at his home. On November 5, 1878, his wife organised a Japanese dinner described by Edmond de Goncourt the next day. The cook was a young Japanese painter, Hosui Yamamoto, who decorated the small Breton house of Judith Gautier (1845-917) with murals in the Japanese style (Bailey Colin B., 1997, p. 165).

In the early years of the review La Vie moderne, created by Georges Charpentier and Émile Bergerat in 1879, Japanese art was also present in the contents: articles on Japonisme (June 26, 1879) then on the Cernuschi collection (May 8, 1880) by the critic Louis Edmond Duranty, and illustrations by Félix Régamey in 1880, when the second volume of the Promenades japonaises was released under the title Tokio-Nikko.

In the years 1880-1890, the Charpentier catalogue continued to honour Japanese culture in different forms. In a critical work published in 1885, Théodore Duret devotes several chapters to Japanese art and Hokusai (Duret T., 1885). In 1888, La Marchande de sourires : pièce japonaise by Judith Gautier was published. Edmond de Goncourt published La Maison d’un artiste in 1881, in which he described his collections, particularly of Japanese art, then reference works on Utamaro in 1891 and Hokusai in 1896.

A Missing Collection?

From the end of the 1870s, Georges Charpentier found himself in financial difficulty. In 1883, he signed a contract with Marpon and Flammarion, which would control a growing share of the capital and lead to an association with Eugène Fasquelle (1863-1952), son-in-law of Charles Marpon (1838-1890). The couple's lavish social life continued, but in a less flourishing context, which is also reflected in their collecting activities.

Georges and Marguerite Charpentier were pioneers in the recognition of Japanese art, but more in its mundane and "decorative" incarnations. The name of Georges Charpentier does not appear among the exhibitors in the Catalogue de l'exposition rétrospective de l'art japonais, organised by Louis Gonse (1846-1921) in 1883.

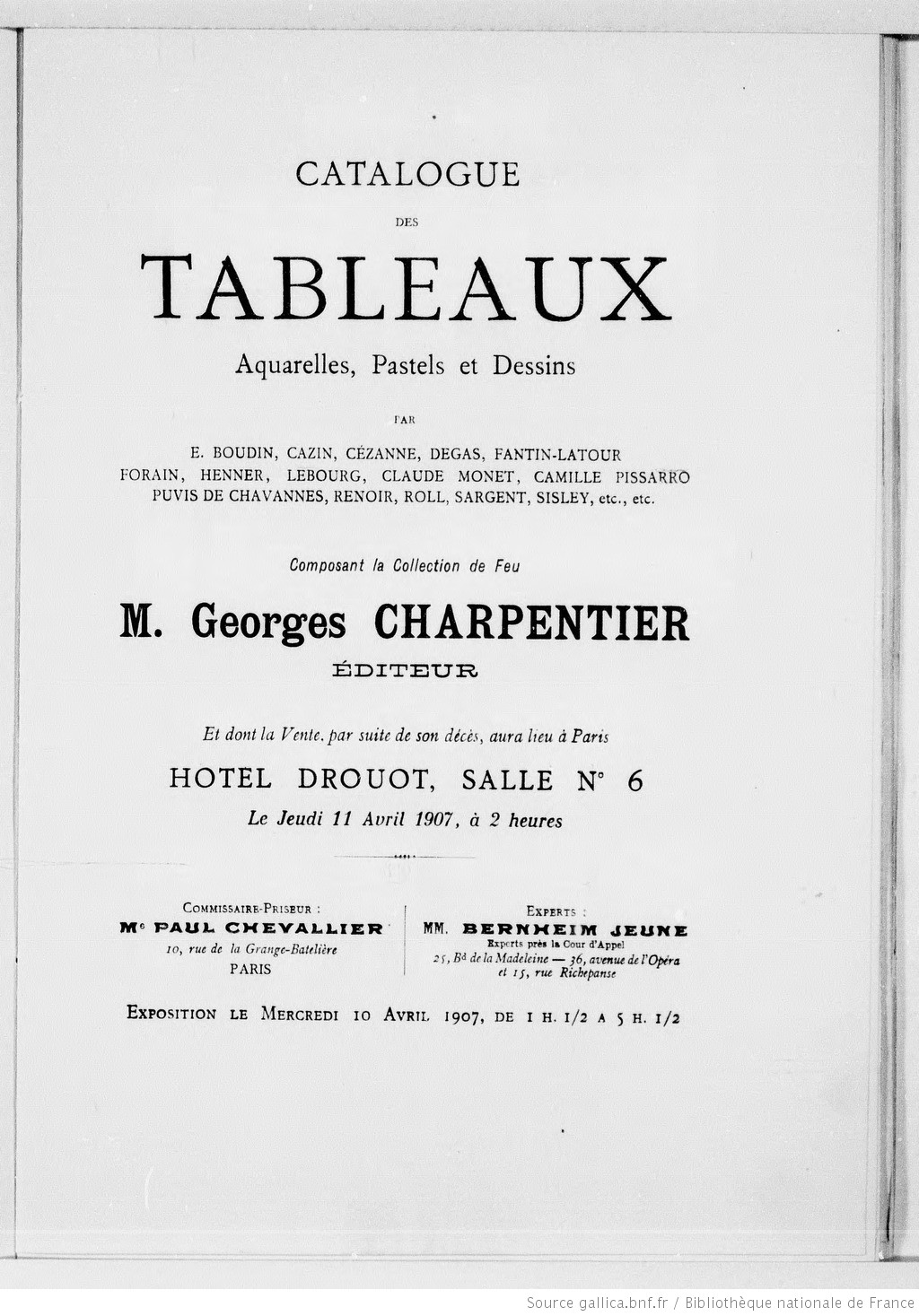

After the death of his son and his retirement from business in 1896, Georges Charpentier left the hotel particulier on rue de Grenelle and no traces remain of their Japanese objects. The sales of the library and works of art in 1907 (the Madame Charpentier et ses enfants by Renoir was sold there to the Metropolitan Museum (inv. 07.122) for a large sum) does not mention Japanese art.

Related articles

Collection / collection d'une personne

Personne / personne