DÈCLE Alexandrine (EN)

The Donor Alexandrine Leclanché, Widow Dècle

Born August 20, 1807 in Châteaudun (AD 28, État civil de 1807, registre des naissances, acte no 87, coté 3 E 88/045), Alexandrine Leclanché (1808-1896), the Widow Dècle, was the daughter of Jean Louis Charles Leclanché (1760-1822) and Françoise Massé (1776-1850). Her father, Charles Leclanché, was “visiteur de rôles” in 1792, then “principal receiver of indirect contributions” in his native town of Châteaudun, and, according to his posthumous inventory, a landowner of significance (August 1, 1822, AD 28, 2 E 15/395).

Alexandrine's brother was the lawyer and man of letters Léopold Leclanché (1813-1871) who distinguished himself by the first complete translation into French of the Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors and Architects by Giorgio Vasari, an editorial undertaking (carried out from 1839 to 1842) that linked him to the painter and lithographer Philippe-Auguste Jeanron (1808-1877), short-lived director of the Musées Nationaux from 1848 to the end of 1849. Appointed Commissioner of the Republic in Amiens (Somme Department) in 1848 , Léopold Leclanché was dismissed in April of the same year (Leclanché L., 1848 and Leclanché L., [s. d.]) and upon the accession of Louis-Napoleon went into exile in England. There, he joined his friend Alexandre-Auguste Ledru-Rollin (1807-1874) and collaborated in the monthly event of the Comité central démocratique européen formed by the former Minister of the Interior of the provisional government of 1848. Léopold Leclanché was listed in 1850 as one of the editors of Proscrit: journal de la République universelle (Brutinel N., 1850). It was probably during this stay in Great Britain that the translator of Giorgio Vasari and Benvenuto Cellini contributed to the French translation project of the works of William Shakespeare led by François-Victor Hugo (1828-1873), between 1859 and 1866. The son of Léopold Leclanché and nephew of Alexandrine was Georges Leclanché (1838-1882), inventor of the electric battery and himself a great collector of Renaissance art (posthumous sale of 1892, in Paris: Mannheim, C., 1892).

Alexandrine Leclanché married Eléonor Dècle (or Eléonore according to the sources), born in 1796 in Amiens and deceased in 1870, was a merchant who resided at 7 rue Neuve-Saint-Eustache in Paris, on May 14, 1825 in Orléans (AM Orléans, 2E104). The couple's fortune came from the textile trade, particularly merino wool, an activity of Eléonor Dècle that was documented from 1828 to 1864 by the various directories of Paris merchants (Verstraete, N., 2016, p. 29). It also came from the couple's financial investments, mainly in the 1860s, as evidenced by the posthumous inventory of Eléonore Dècle (AN, MC/ET/XLVII/1040).

Alexandrine Leclanché, the Widow Dècle, died on October 27, 1896 in Paris (AP, 9e arrondissement, État civil de 1896, registre des décès, acte no 1090, coté V4E8832).

A Couple’s Collection and Life

As Alexandrine Leclanché, the Widow Dècle (1808-1896), specified in the version of her will of April 3, 1882 (AN, MC/ET/XCVIII/1309), the property forming the collection of the Dècle spouses “did not come from inheritance", but was brought together through Eléonor Dècle's trading activity and the couple's investments in the financial markets. No mention in the archives or the donor's correspondence make it possible to specify the precise means of acquisition of this collection, except for the very slim indication of a certain Mr. G. Fournier who was designated by Alexandrine Dècle to serve as an expert of her collection upon her death (along with Charles Mannheim) (AN, MC/ET/XCVIII/1309). As a dealer in antiquities, works of art and paintings (Verstraete, N., 2016, p. 43), the latter played an intermediary role with Sèvres when the Dècle bequest was distributed (MMMS, 4W669/ legs Dècle (1897)/correspondance).

The Preparation of the Bequest; the Role of Edmond du Sommerard

The many versions of Alexandrine Dècle's wills and codicils, which span from 1870 to 1896 (AN, MC/ET/XCVIII/1309), reveal plans for a bequest to benefit a museum institution from 1880, initially for the sole benefit of the Cluny Museum. The curator Edmond du Sommerard (1817-1885) then took on the task of looking for museums that were likely to receive objects that would not be retained by his institution (in particular the paintings and engravings from the collection).In 1884, he forged the first links on this subject with the musée de Dijon (MMAC, legs Dècle). Other exchanges between the representatives of the donor and the Manufacture de Sèvres are attested during the year 1890: the project then under discussion concerned a bequest of porcelain, earthenware, stained glass and enamels (as well as miniatures and objects of metalwork) and was accompanied, on the part of Alexandrine Dècle, by several anticipated donations, in particular pieces of European porcelain (MMMS, 4W669/legs Dècle (1897)/correspondance). The provisions of 1890 formalise the legacy’s new beneficiary, along with the musée des Arts décoratifs in Paris, which had just then come into existence.

The Distribution of the Bequest; the Entry of the Collection into the Public Domain

By her will of April 15 and codicil of June 7, 1892 with Maître Paul Girardin, notary in Paris (85 rue Richelieu), Alexandrine Leclanché, the Widow Dècle, ultimately bequeathed her collections to the museums of Cluny, Sèvres and the decorative arts, as well as to the museum of Dijon. The museum of Dijon received works from her library, furniture, bronzes and decorative objects, including "figures and chimeras of Japan", two world maps, and all the paintings, drawings, engravings, pastels, watercolours from her Parisian residence at 20 rue de Navarin (the total was "estimated by the experts of the Dècle family at 26,770 francs") and her country house in Yerres (estimated at 3,162 francs). In addition, 124 objects of Oriental and Western porcelain were refused by the museums of Cluny (167 numbers retained in the end) and Sèvres (entry of 95 numbers), which increased the bequest to Dijon. The latter (208 numbers) was presented in its final constitution to the Dijon museum commission of November 12, 1897 and was accepted by the municipal council of November 27, 1897, whose report specifies that "porcelain from Japan, Sèvres and Saxony, taken over by the city, in accordance with the provisions […] of the codicil of June 7, 1792” have a value “of approximately 10,353 francs”. The city council endorsed the opinion of the museum commission that "it would be appropriate to allocate a special showcase intended to expose to the public eye objects from Saxony, Sèvres, China and Japan" from this bequest. The board of directors of UCAD confirmed the receipt of the Dècle legacy (165 entries in the inventory) on October 29, 1897, although it was not until August 13, 1898 that a decree of acceptance of the bequest of Madame the Widow Décle was signed by the state.

Exhibition of the Dècle Collection

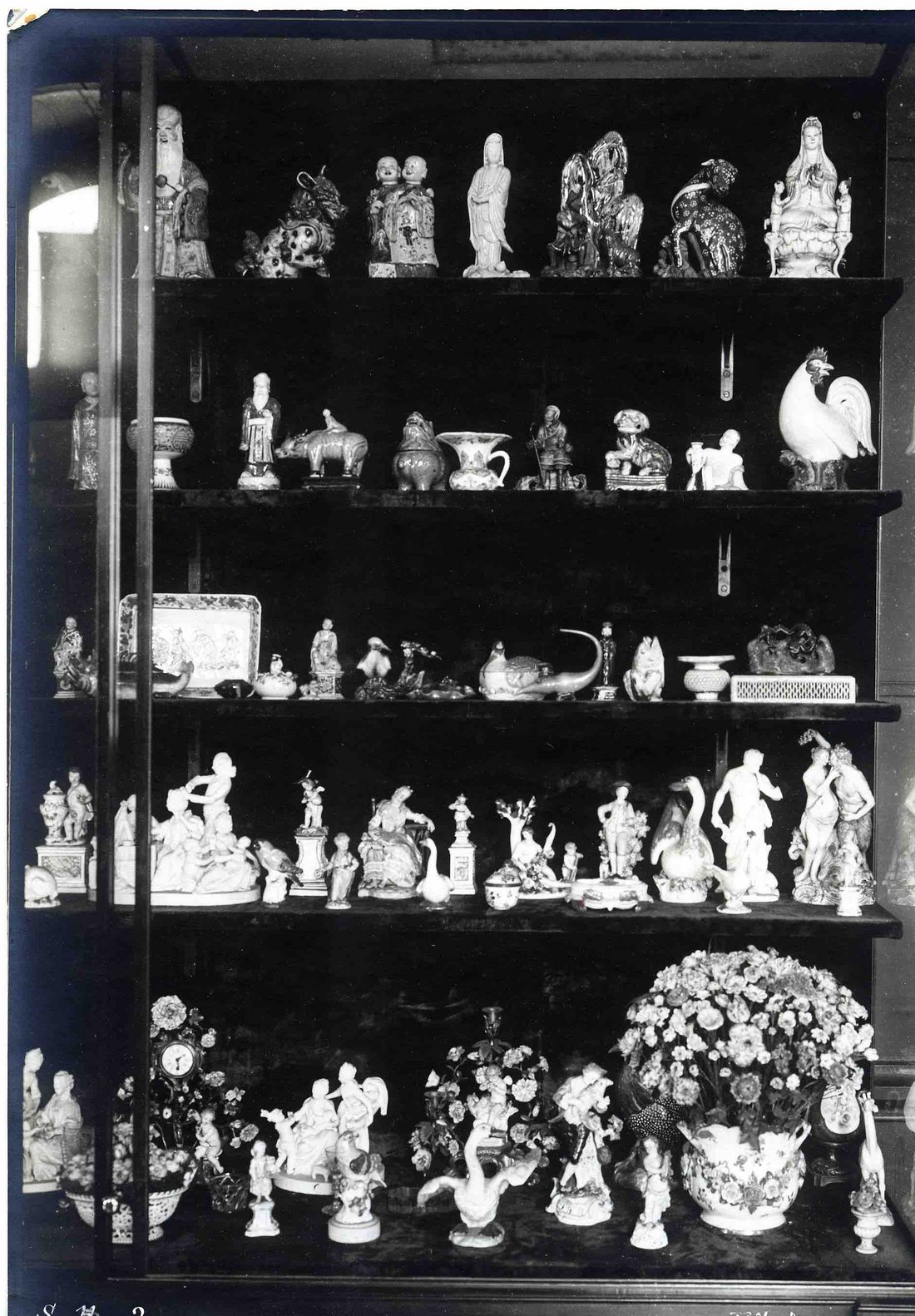

At the time of the bequest or even from the negotiations prior to it, the presentation of works from the Dècle collection was envisaged in the form of an exhibition room specific to the Manufacture de Sèvres (in the museum or in the library, for study purposes for artists) and the musée de Dijon. In May 1900, a new room in the latter - taken from the rooms forming the “musée Trimolet" - was dedicated to the Dècle collection, in the building’s 19th-century wing. Excepting certain pieces of furniture and "trinkets of luxury rather than of art", which were "reserved for the cabinet of M. le Conservateur" (Chabeuf, H., 1900), this presentation consisted of the paintings from the bequest and a large showcase of more than a hundred ceramics (two photographs of the showcase are preserved in the documentation of the museum). The collection of art objects (140 pieces) from the Dècle bequest in Dijon shows a predominance of statuettes and small ceramic groups in which European and Asian porcelains (mainly China, Japan, and Korea) are represented separately in comparable proportion (65 entries under an Asian origin). The set of 67 paintings stands out for its coherence and unity: paintings from the 17th and 18th centuries, with a few forays into the 19th century, by French, Flemish, German and Italian masters; mostly of small format, with the exception of the paintings by Trinquesse (L’Offrande à Vénus, inv. DE 22 and Le Serment à l’amour, inv. DE 23), they are always finely painted, have a deliberately porcelain style, and depict mythological or gallant subjects, genre scenes, and landscapes.

Related articles

Collection / collection d'une personne

Personne / personne