BERTIN Henri Léonard (EN)

Biographical Article

Henri Léonard Jean-Baptiste Bertin was the twelfth child of Jean Bertin (1679-1754), advisor to the Parliament of Bordeauxsince 1711, and his wife Marie-Lucrèce de Saint-Chamans. When he was born in 1720, the acquisition of offices and titled land as well as the marriages made by successive generations enabled the Bertins, who were members of the bourgeoisie of Périgueux and owners of iron works, to attain the position of major landowners embellished with the appearances of nobility. The qualities detected in the young Henri Léonard Jean-Baptiste convinced his father to name him as the principal heir to his fortune and duties. Although it caused a tragic conflict with the family’s eldest child, who would be imprisoned from 1752 until his death in 1779, this choice would confer upon the designated child the responsibility of a clan chief. His rise was rapid: after studying law in Paris (1737-1740), he was admitted as a lawyer at the Parliament of Bordeaux in 1741, then as an advisor to the Grand Council. In 1745, his father resigned his position of Master of Requests (maître des requêtes), which he had obtained in 1724, in his favour. Benefiting from the patronage of the Maréchal de Noailles and the Marquise de Pompadour, he obtained the commission of president at the Grand Counseil in 1749 and was appointed intendant in Roussillon the following year (1750). Following a conflict with the governor of Roussillon and the local nobility, the source of which was opposition at the highest levels of state between the Count d'Argenson, Secretary of State for War, and Madame de Pompadour, Bertin was dismissed in 1753; however, he swiftly returned to higher responsibilities in 1754 as the king's steward in Lyon, where he manifested a particular interest in the development of routes, for the Givors canal project, which marked the beginning of the link between the Rhône and the Loire, as well as for the silk industry. In November 1757, the duties of lieutenant general of police brought him back to Paris. Two years later, in November 1759, with the Seven Years' War increasing the difficulty of the task, he accepted the post of Comptroller General of Finances, thus succeeding Silhouette, whose fiscal policies had led to his dismissal. While increasing taxes, Bertin planned to create a land registry (cadastre), aiming to establish a more equitable basis. He advocated for the free movement of grain, promoted the development of agricultural societies, and in 1761 brought a project into fruition to create a veterinary school in Lyon. He also took the initiative to give a historical orientation to the work of compiling legislative texts entrusted under his predecessor to the lawyer Jacob Nicolas Moreau (1717-1803), who from 1762 collected copies of French and then foreign archives within the "cabinet of history" or "cabinet of charters". Although involved in petty quarrels with Choiseul, who then controlled the levers of military and diplomatic action, Bertin was able to rely on the friendship and support of the King and Madame de Pompadour. At the end of 1762, he was promoted to Minister of State, giving him access to the high council, and made Grand Treasurer of the ordre du Saint-Esprit. A few months earlier, he acquired an old manor in Chatou, the beginning of a domain that he would gradually expand and aspired to make the site of agronomical experiments. As testimony to the favour he enjoyed, a new ministerial department was created for him, bringing together the areas of action in which he was interested, taken from among the attributions of the comptroller general of finances. This fifth Secretary of State - Bertin's detractors would speak of the "small ministry" - was mainly responsible, after its creation, for porcelain factories, certain aspects of horse farms, agricultural and veterinary matters, mines, transport by land and by water, certain aspects of lotteries, Moreau's historical cabinet, the Compagnie des Indes, and factories of painted canvas and cotton. His most notable achievements would be the renovation of agriculture, the creation of the veterinary schools of Lyon (1764) and Alfort (1766), the rationalisation of the administration of the mines, which would lead in particular, in 1783, to the creation of the École des Mines, and the rise of the cabinet of charters.

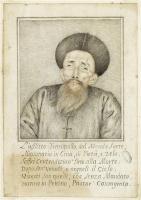

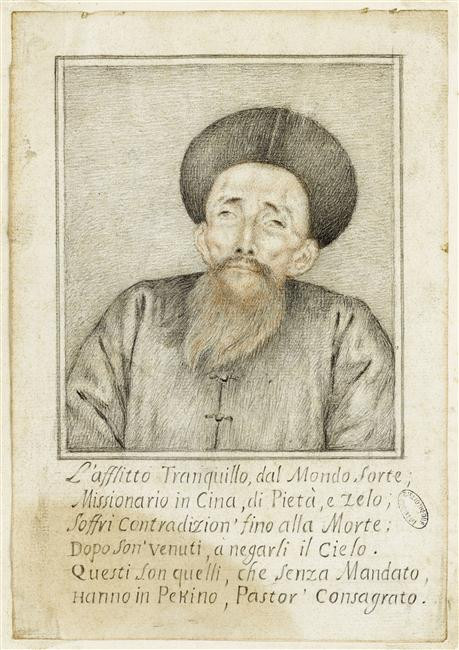

The most novel undertaking, however, was the one beginning in 1764 when Bertin welcomed two young Chinese Catholics, Louis Ko and Étienne Yang, who had been sent to France ten years earlier by Jesuit missionaries from Beijing. After studying at the Jesuit colleges of La Flèche and of Paris, after the opponents of the Society of Jesus managed to have them banned in France, Ko and Yang asked the Secretary of State for permission to book passage on a ship from the East India Company in order to return to their homeland. Bertin realised that the relations he could establish with these two young Chinese scholars, who had the patronage of the king, could provide a unique opportunity to acquire a more precise and in-depth knowledge of the Middle Empire and to borrow the principles and savoir-faire which in the eyes of enlightened circles in France marked its superiority in numerous fields, notably the political, economic, and technical. And for this knowledge to be as useful as possible in France, the two young Chinese men should gain as precise a vision as possible of their host country's state of science and technology. Thus, after encouraging them to extend their stay, Bertin had them trained in French knowledge, particularly in the fields of natural sciences, physics, chemistry, drawing, engraving, and printing, in particular by taking them to visit factories during a trip to Lyon, Saint-Étienne, and the surrounding areas. In January 1765, they finally departed, furnished with gifts and instructions defining the principles of the correspondence that they were expected to maintain from China and all the information and specimens that they needed to collect and send to their patrons. Following Ko and Yang’s arrival in Beijing, a continuous exchange of memoirs, books, objects and works of art was launched, with the two young Chinese receiving assistance in this enterprise from French missionaries in Beijing, led by Father Joseph-Marie Amiot (1718-1793). Upon its arrival in France, the documentation was analysed under the direction of scholars Abbé Charles Batteux (1713-1780) and then Louis Georges Oudard Feudrix de Bréquigny (1714-1795), commissioned by Bertin to ensure its publication. Fifteen volumes of Mémoires concernant l’histoire, les sciences, les arts, les mœurs, les usages, etc. des Chinois [...] appeared from 1776 to 1791. As for the manuscripts, prints, paintings, and all manner of objects, they largely went on to form the minister's Chinese cabinet, as exceptional for its richness as for its origins. Bertin's parallel actions in favour of the cabinet of charters and his literary and scientific correspondence with China justified his presence at the Académie des sciences, of which he was an honorary member (1761), vice-president (1763-1769), and president (1764-1770), as well as at the Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres, of which he was an honorary member from 1772 (Huard P., Wong M., 1966).

Bertin retained his ministry upon the accession of Louis XVI. As the king had chosen Vergennes, then ambassador in Stockholm, as secretary of state of foreign affairs, Bertin was given the responsibility in the interim until the arrival of the new minister. However, there was to be no question of kindling a friendship like the one he had enjoyed with Louis XV with the new king. The distrust of Necker, appointed head of finance in 1776, with regard to the "small ministry" and the discovery, in 1778, of embezzlement committed at the Sèvres factory under his authority, led to Bertin’s resignation in May 1780 and to the abolition of his role as secretary of state a few months later.

After resigning from his position as grand treasurer of theking's ordersin February 1781, Bertin nonetheless retained unrelenting responsibility for the literary and scientific correspondence with China. In April 1781, he settled permanently in Chatou, where he had entrusted Soufflot (1713-1780) with the construction of a new château. Still single, he was accompanied by a brother, Abbé de Bertin, and a sister, Mlle de Creyssac.

Alarmed by the disorders of the summer of 1789, the former secretary of state left France, probably in the summer of 1791 (Silvestre de Sacy J., 1970, p. 154) and went to stay in Aachen, where he proceeded remotely with the liquidation of his properties. A frequent visitor to the waters of Spa, he died there on September 16, 1792.

The Collection

While, considering his longstanding interest in China and the general enthusiasm for its culture, it seems unlikely that Bertin would not have had a few Chinese works of art in his personally possession before 1766, particularly porcelain, what should be considered as his Asian collection or collections are the objects, books, and documents sent to him by the French missionaries following Ko and Yang’s return to Beijing in 1766, including objects dispatched on behalf of Emperor Qianlong himself. These documents, objects and other specimens were frequently sent in response to specific orders from Bertin (Bienaimé C., Michel P., 2014, p. 153). As part of Bertin's official functions, they contributed to the formation of a personal collection, which the minister wished to make available to scholars and the content of which he intended to disseminate through Mémoires concernant l’histoire, les sciences, les arts, les mœurs, les usages, etc. des Chinois. Some of the shipments received by Bertin were gifts intended for his brothers and sisters or the king; the minister himself offered certain pieces, such as to Madame de Pompadour (see for example Monnet N., 2014b, p. 169). The French missionaries in Beijing thus had to double their shipments of books, either by sending two copies, or by making an additional manuscript copy, one copy being sent to Bertin and the other intended for the king's library. The finest copies were sent to the Minister (Huard P., Wong M., 1966, p. 158 and 224; Monnet N., 2014a, p. 144). The multiplicity of shipments can make it difficult to distinguish between the works specifically belonging to Bertin's collection and those that arrived in France through his relationship with the Beijing mission, without entering the minister's collection. Within the albums of accumulated prints and paintings are “ ‘authentic’ Chinese albums, unrelated to the project of the Mémoires", and albums specially made in China as part of this (Bienaimé C., Michel P., 2014, p. 153). Thus, manuscripts and printed books in French and Chinese are brought together, including xylographic editions, and an exceptional set of drawings and paintings that particularly document the fauna and flora, cultures, arts, trades and techniques, landscapes, constructions, costume, rituals, religious pantheon, and history. Focusing on the example of Chinese vases, Kee Il Choi Jr (2018) described the methods of sending albums and images and the methods by which they were classified, bound, captioned, and annotated. An overview of the objects from China that also make up the collection was provided in 1786 by Luc-Vincent Thiéry's Guide des amateurs et des étrangers voyageurs à Paris, which insisted on the collection of musical instruments, minerals, the clothing and ornaments of mandarins, lacquers and varnishes, bamboo and ivory, porcelain, coins, blocks of wax, models of plows and wheelbarrows (Thiéry L.-V., 1786-1787, t. I, p. 135-136). This list can be completed by mentioning vases, boxes, pots, figurines, pagodas, fans, screens, and mats (AN, F/17/1188 and 1231). For information on the various categories of objects, see Silvestre de Sacy J. (1970), p. 167, as well as Huard P. and Wong M. (1966), p. 166-167.

Minerals and naturalia from China also enriched the minister's cabinets of natural history and mineralogy (Huard P., Wong M., 1966, p. 142).

A compilation of the lists of objects sent from China from 1765 to 1786 is preserved in Bertin's papers in the library of the Institut (Ms. 1524, fo 126-193v)). A methodical comparison of the content of the 17 tomes of the Mémoires concernant les Chinois between 1776 and 1791, then in 1814, and source texts from China, was proposed by Father Joseph Dehergne (1983).

From the treasures received from Peking, Bertin set up a Chinese cabinet in his Parisian home, located at the corner of the boulevards and what was then the rue Neuve des Capucines, which was also the seat of the "small ministry". The existence of the firm is mentioned in a letter from Bertin to Ko and Yang dated January 18, 1774 (BIF, Ms. 1522). The most detailed description is the one provided by Thiéryin 1786.

In April 1781, Bertin, who was released from his ministerial duties, moved to Chatou (Bussière G., 1909, p. 278). His process of settling into Chatou and Montesson began in 1761, with the acquisition of an old manor; his domain continued to grow in the 1760s and 1770s, through successive acquisitions (Curmer A., 1919, p. 125-127). He entrusted Jacques Germain Soufflot (1713-1780), who was in full activity in Lyon when Bertin was the intendant there (1754-1757), with the layout of the gardens and the construction of a new chateau. Soufflot notably involved his collaborators Jean-François Chalgrin (1739-1811), Jean Rondelet (1743-1829), and Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757-1826) (Catinat J., 1974, p. 28, 38, 40-43, 70). In addition to hydrangeas, known as Chinese roses, and peony trees from Beijing (Catinat J., 1974, p. 94), the gardens were embellished with two constructions celebrating the master’s passions: a Chinese ring game and a Chinese pavilion, designed by Lequeu, and whose appearance is known from several drawings. The ring game derives from the one built by Lequeu in Monceau for the Duke of Chartres (Catinat J., 1974, p. 38-41, Rochebrune M.-L., 2014, p. 268-269).

The disposition of Bertin's collections after his move to Chatou is not known with absolute certainty. According to Curmer and Bussière, Bertin's library and collections did indeed join their master at Chatou, where, according to the later, the originals of the Mémoires concernant les Chinois, the written and figurative documentation, and the correspondence received from the missionaries occupied the largest room in the house (Curmer A., 1919, p. 147-148; Bussière G., 1909, p. 161, 240). It can be recalled that in 1786-1787 the Guide des amateurs et des étrangers voyageurs à Paris describes the collection in Bertin’s Parisian home. Despite Hillairet's indication (1963, t. I, p. 267) that Bertin bequeathed this hotel to his sister and niece in 1785, who in turn sold it in 1786, no source specifically testifies to the collection’s transfer to Chatou. On the other hand, some documents attest to Bertin's intentions to give his office there a particularly refined setting: memoranda intended for Father François Bourgeois, of the Beijing mission, mention Bertin's wish to build an authentically Chinese building in the gardens of Chatou and request the expertise of a Chinese architect for this purpose (BIF, Ms. 1526, fo 40-46 et Ms. 1524, fo 104-107v; INHA, Ms. 131, fo 91; see Bienaimé C., 2013, p. 142, Finlay J., 2015, p. 91, Finlay J., 2020, p. 108-109). In a letter from Father Amiot to Bertin, dated October 16, 1790, the missionary responded to the request, which had been expressed almost a year earlier by the former minister, to "lead him in the arrangement of his Chinese cabinet" in Chatou, aiming to confer on him a distribution and a decoration in full harmony with the collected objects. Said letter was accompanied by several boxes containing the elements of the Chinese decoration of the different spaces meant to form the future cabinet (BIF, Ms. 1517, fo 139, quoted by Bussière G., 1909, p. 159-161, Bienaimé C., 2013, p. 142, Bienaimé C. and Michel P., 2014, p. 156-157). Although Jacques Catinat (1974, p. 108) believed he could estimate that the Chinese cabinet was almost completed in the new château in 1790, sources are lacking to confirm that the entire collection was transferred there. The former printer and bookseller Louis François Delatour (1727-1807) probably commented on the Parisian layout of the Chinese cabinet in his Essais sur l'architecture des Chinois (1803, p. 172), when he spoke of the "lack of arrangement and order" in Bertin's "magnificent cabinet of Chinese curiosities". One of the major features of the collection, underscored by Bertin himself, was that it was generously made available to the curious, scholars, and artists, who could find specimens and models in it (see in particular Bienaimé C., 2013 , pp. 143-144 and Rochebrune, M.-L., 2014, pp. 155, 175-177, 198, 228, 230, 236).

In the summer of 1789, however, the dispersal began. Bertin, who had neither wife nor child, proceeded with the sale or donation of his land in 1790 and 1791; a large part of these transactions were conducted by his secretary and attorney François Étienne Fouillette-Desvoyes (Bussière G., 1909, pp. 279-280). The Chatou estate was sold to Anne Marie Thérèse de Pelser-Berensberg, the future Marquise de Feuquières, who settled there. In the absence of more precise sources on the collection, we must rely on Delatour's testimony, according to which the cabinet would have “passed into other hands by dispersion before 1791, or by the sale that the former minister, who was stripped of his pensions and his fortune, was obliged to make” (Delatour L. F., 1803, p. 244). After Bertin’s death (September 1792), the disappearance of his collection was full of intrigue. In December 1793, summoned before the committee of general security, Desvoyes offered his help "to, if possible, recover the remains of this cabinet that was mutilated in transport, dilapidated elsewhere, and donated by Bertin in 1790" (AN, F /17/1072, d. 5 and Tuetey L., 1912, t. I, p. 370). The search would be carried out as far as Périgord (Tuetey L., 1912, t. II, p. 170). About fifteen works were discovered in January 1794 at the home of the engraver Isidore Stanislas Helman (1743-1806?), whose interest in the Franco-Chinese artistic undertakings of Bertin was well known, and who certified that they had been left with him in 1785 and in April 1789 (AN, F/17/1231, d. 4, F/17/1269 and Tuetey L., 1912, t. I, p. 54 and 60). Desvoyes' research led to the discovery of nearly 250 articles in Paris, which had been deposited in the Muséum national on rue de Beaune, also known as the Nesle depository (dépôt de Nesle), where they were inventoried in April 1794 (AN, F/17/ 372, pp. 18-20, F/17/1072, d. 5, F/17/1188). It should be noted that when an inventory was made of the furniture in the château de Chatou in the autumn of 1794, after the execution of the Marquise de Feuquières, there was no indication that items belonged to Bertin (Curmer A., 1919, p. 184-185).

The annotations made in the registry of the Nesle depot (F/17/372) show the distribution of the remaining objects: 109 items consisting of manuscript and printed books and paintings were intended for the Bibliothèque national; 40, consisting of minerals, for the dépôt des Mines (see on this specific subject Laboulais I., 2013, p. 183); of the 161 items consisting of objects or works of art, a large part was intended for the Muséum d’histoire naturelle, the Muséum des antiquités, or the Bibliothèque nationale. Manuscripts and printed books, paintings and other figurative documents were transferred to the Bibliothèque nationale in 1794 and April 1796, where they were divided between the département des Manuscrits and the cabinet des Estampes (BnF, Estampes, Réserve, Y E-1 (1797-1808) – PET FOL, parts 397-399, 401, 402; Tuetey L., 1912, t. I, p. 87, Balayé S., 1988, p. 420, Monnet N., 2014a, p. 144, Cohen M. (online)). In September 1796, 97 objects or works of art were transferred to the cabinet or Muséum des Antiques, an ethnographic conservatory established above the cabinet des Médailles (Hamy E. T., 1890, p. 29, 83-86). (On the fate of Chinese collections, see also Finlay J., 2020, p. 148-149.)

In 1811, the Parisian bookseller Antoine Nepveu published La Chine en miniature, ou choix de costumes, arts et métiers de cet empire, représentés par 74 gravures [...], by Jean-Baptiste Breton de la Martinière, a work whose preface lays out its essential material as Bertin's collection of "about 400 original drawings made in Peking, of the arts and crafts of China", "chance" having provided Nepveu with the opportunity to acquire it almost entirely, along with the correspondence between Bertin and the missionaries Ko and Yang (Breton de la Martinière J.-B., 1811, p. XXI-XXII). In this way, elements of the collection that probably disappeared during the first years of the Revolution resurfaced. A number of pieces from Bertin's collection also joined the département des Estampes through a purchase at the Delatour sale in 1810, as well as through a purchase from Nepveu (Balayé S., 1988, p. 421, n 374; Guibert J., 1926, p. 126, 236; BnF, Estampes, Réserve, Y E-1 (1797-1808) – PET FOL, parts 400-401).

During the first decades of the 19th century, parts of Bertin's collections reappeared at several public sales. The first and major one, which took place on February 1815, was mainly composed of objects (169 lots representing around 500 items). The results of this sale are unfortunately not known. According to the catalogue (Notice des articles curieux composant le cabinet chinois de feu M. Bertin. Paris: Imprimerie de Crapelet, 1815), which is certainly inaccurate on this point, the collection consisted of Bertin's entire Chinese cabinet, complemented by some Persian objects. In April 1828, a sale at the behest of Auguste Nicolas Nepveu brought together Chinese and Japanese paintings, lacquerware, porcelain, and other objects from China, notably from Bertin's cabinet. In March 1832, the sale of the Théodore Moreau collection also brought together books, manuscripts, and objects of Chinese and Japanese origin, notably from the Bertin collection. Without doubt alongside many others, Jean Huzard (1735-1838), director of the Alfort school (Huard P., Wong M., 1966, p. 142-143, n. 5, p. 158), and Chrétien Louis Joseph de Guignes (1759-1845) also owned fragments of the collection during these years.

In June 1830, Nepveu sold Bertin's correspondence with the Beijing missionaries as well as with Ko and Yang to Baron Benjamin Delessert (1773-1847). In 1874, they were bequeathed to the library of the Institut by Baron François Marie Delessert (1780-1868) [BIF, Ms. 1515-1526; Huard P., Wong M., 1966, p. 142, no. 5; Bienaimé C., Michel P., 2014, p. 164-165). The papers of Bréquigny, who was the successor to Abbé Batteux at the head of the Mémoires concernant les Chinois, were bequeathed to his collaborator La Porte du Theil. These papers entered the département des Manuscrits of the Bibliothèque nationale after the latter’s death in 1815 (see Dehergne J. [1983], who describes the dispersal of the documentation used in the Mémoires, and Silvestre de Sacy J. [1970], p. 170).

In 1880, the objects attributed to the Muséum des antiques and the Bibliothèque nationale in 1796, possibly enriched with others, were handed over to the musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro, predecessor of the musée de l’Homme (Hamy E. T., 1890, p.29); as was the case, in particular, with musical instruments (Picard F., 2006, p. 23-24). Alongside the large collections now kept in the Bibliothèque nationale and the Bibliothèque de l’Institut, a large number of objects and especially books and illustrated documents are still reported in public collections. The manuscripts and albums representing animals and plants held by the Muséum d’histoire naturelle (cited by Huard P., Wong M., 1966, p. 158, 224, 225) and the manuscripts on the manufacture of porcelain and on the Chinese vases are preserved in particular by the libraries of the manufacture nationale de Sèvres and the INHA, as noted by Huard P. and Wong M. (1966, p. 226) and Kee Il Choi Jr (2018).

While considering his longstanding interest in China and the general enthusiasm for its culture, it seems likely that Bertin was personally in possession of a few Chinese works of art before 1766, particularly porcelain. What should be considered as Bertin's Asian collection or collections is effectively the sum of objects, books, and documents sent to him after the return of Ko and Yang to Beijing in 1766, by the French missionaries there, and others from the Qianlong Emperor himself. These documents, objects and other specimens were frequently sent in response to specific orders from Bertin (Bienaimé C., Michel P., 2014, p. 153). As part of Bertin's official functions, they contributed to the formation of a personal collection, which the minister wished to make available to scholars and the content of which he intended to disseminate through Mémoires concernant l’histoire, les sciences, les arts, les mœurs, les usages, etc. des Chinois. Some of the shipments received by Bertin were gifts intended for his brothers and sisters or the king; the minister himself offered certain pieces, such as to Madame de Pompadour (see for example Monnet N., 2014b, p. 169). The French missionaries in Beijing thus had to double their shipments of books, either by sending two copies, or by making an additional manuscript copy, one copy being sent to Bertin and the other intended for the king's library. The finest copies were sent to the Minister (Huard P., Wong M., 1966, p. 158 and 224; Monnet N., 2014a, p. 144). The multiplicity of shipments can make it difficult to distinguish between the works specifically belonging to Bertin's collection and those that arrived in France through his relationship with the Beijing mission, without entering the minister's collection. Within the albums of accumulated prints and paintings are “ ‘authentic’ Chinese albums, unrelated to the project of the Mémoires", and albums specially made in China as part of this (Bienaimé C., Michel P., 2014, p. 153). Thus, manuscripts and printed books in French and Chinese are brought together, including xylographic editions, and an exceptional set of drawings and paintings that particularly document the fauna and flora, cultures, arts, trades and techniques, landscapes, constructions, costume, rituals, religious pantheon, and history. Focusing on the example of Chinese vases, Kee Il Choi Jr (2018) described the methods of sending albums and images and the methods by which they were classified, bound, captioned, and annotated. An overview of the objects from China that also make up the collection was provided in 1786 by Luc-Vincent Thiéry's Guide des amateurs et des étrangers voyageurs à Paris, which insisted on the collection of musical instruments, minerals, the clothing and ornaments of mandarins, lacquers and varnishes, bamboo and ivory, porcelain, coins, blocks of wax, models of plows and wheelbarrows (Thiéry L.-V., 1786-1787, t. I, p. 135-136). This list can be completed by mentioning vases, boxes, pots, figurines, pagodas, fans, screens, and mats (AN, F/17/1188 and 1231). For information on the various categories of objects, see Silvestre de Sacy J. (1970), p. 167, as well as Huard P. and Wong M. (1966), p. 166-167.

Minerals and naturalia from China also enriched the minister's cabinets of natural history and mineralogy (Huard P., Wong M., 1966, p. 142).

A compilation of the lists of objects sent from China from 1765 to 1786 is preserved in Bertin's papers in the library of the Institut (Ms. 1524, fo 126-193v)). A methodical comparison of the content of the 17 tomes of the Mémoires concernant les Chinois between 1776 and 1791, then in 1814, and source texts from China, was proposed by Father Joseph Dehergne (1983).

From the treasures received from Peking, Bertin set up a Chinese cabinet in his Parisian home, located at the corner of the boulevards and what was then the rue Neuve des Capucines, which was also the seat of the "small ministry". The existence of the firm is mentioned in a letter from Bertin to Ko and Yang dated January 18, 1774 (BIF, Ms. 1522). The most detailed description is the one provided by Thiéryin 1786.

In April 1781, Bertin, who was released from his ministerial duties, moved to Chatou (Bussière G., 1909, p. 278). His process of settling into Chatou and Montesson began in 1761, with the acquisition of an old manor; his domain continued to grow in the 1760s and 1770s, through successive acquisitions (Curmer A., 1919, p. 125-127). He entrusted Jacques Germain Soufflot (1713-1780), who was in full activity in Lyon when Bertin was the intendant there (1754-1757), with the layout of the gardens and the construction of a new chateau. Soufflot notably involved his collaborators Jean-François Chalgrin (1739-1811), Jean Rondelet (1743-1829), and Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757-1826) (Catinat J., 1974, p. 28, 38, 40-43, 70). In addition to hydrangeas, known as Chinese roses, and peony trees from Beijing (Catinat J., 1974, p. 94), the gardens were embellished with two constructions celebrating the master’s passions: a Chinese ring game and a Chinese pavilion, designed by Lequeu, and whose appearance is known from several drawings. The ring game derives from the one built by Lequeu in Monceau for the Duke of Chartres (Catinat J., 1974, p. 38-41, Rochebrune M.-L., 2014, p. 268-269).

The disposition of Bertin's collections after his move to Chatou is not known with absolute certainty. According to Curmer and Bussière, Bertin's library and collections did indeed join their master at Chatou, where, according to the later, the originals of the Mémoires concernant les Chinois, the written and figurative documentation, and the correspondence received from the missionaries occupied the largest room in the house (Curmer A., 1919, p. 147-148; Bussière G., 1909, p. 161, 240). It can be recalled that in 1786-1787 the Guide des amateurs et des étrangers voyageurs à Paris describes the collection in Bertin’s Parisian home. Despite Hillairet's indication (1963, t. I, p. 267) that Bertin bequeathed this hotel to his sister and niece in 1785, who in turn sold it in 1786, no source specifically testifies to the collection’s transfer to Chatou. On the other hand, some documents attest to Bertin's intentions to give his office there a particularly refined setting: memoranda intended for Father François Bourgeois, of the Beijing mission, mention Bertin's wish to build an authentically Chinese building in the gardens of Chatou and request the expertise of a Chinese architect for this purpose (BIF, Ms. 1526, fo 40-46 et Ms. 1524, fo 104-107v; INHA, Ms. 131, fo 91; see Bienaimé C., 2013, p. 142, Finlay J., 2015, p. 91, Finlay J., 2020, p. 108-109). In a letter from Father Amiot to Bertin, dated October 16, 1790, the missionary responded to the request, which had been expressed almost a year earlier by the former minister, to "lead him in the arrangement of his Chinese cabinet" in Chatou, aiming to confer on him a distribution and a decoration in full harmony with the collected objects. Said letter wasaccompanied by several boxes containing the elements of the Chinese decoration of the different spaces meant to form the future cabinet (BIF, Ms. 1517, fo 139, quoted by Bussière G., 1909, p. 159-161, Bienaimé C., 2013, p. 142, Bienaimé C. and Michel P., 2014, p. 156-157). Although Jacques Catinat (1974, p. 108) believed he could estimate that the Chinese cabinet was almost completed in the new château in 1790, sources are lacking to confirm that the entire collection was transferred there. The former printer and bookseller Louis François Delatour (1727-1807) probably commented on the Parisian layout of the Chinese cabinet in his Essais sur l'architecture des Chinois (1803, p. 172), when he spoke of the "lack of arrangement and order" in Bertin's "magnificent cabinet of Chinese curiosities". One of the major features of the collection, underscored by Bertin himself, was that it was generously made available to the curious, scholars, and artists, who could find specimens and models in it (see in particular Bienaimé C., 2013 , pp. 143-144 and Rochebrune, M.-L., 2014, pp. 155, 175-177, 198, 228, 230, 236).

In the summer of 1789, however, the dispersal began. Bertin, who had neither wife nor child, proceeded with the sale or donation of his land in 1790 and 1791; a large part of these transactions were conducted by his secretary and attorney François Ėtienne Fouillette-Desvoyes (Bussière G., 1909, pp. 279-280). The Chatou estate was sold to Anne Marie Thérèse de Pelser-Berensberg, the future Marquise de Feuquières, who settled there. In the absence of more precise sources on the collection, we must rely on Delatour's testimony, according to which the cabinet would have “passed into other hands by dispersion before 1791, or by the sale that the former minister, who was stripped of his pensions and his fortune, was obliged to make” (Delatour L. F., 1803, p. 244). After Bertin’s death (September 1792), the fate collection was full of intrigue. In December 1793, summoned before the committee of general security, Desvoyes offered his help "to, if possible, recover the remains of this cabinet that was mutilated in transport, dilapidated elsewhere, and donated by Bertin in 1790" (AN, F /17/1072, d. 5 and Tuetey L., 1912, t. I, p. 370). The search would be carried out as far as Périgord (Tuetey L., 1912, t. II, p. 170). About fifteen works were discovered in January 1794 at the home of the engraver Isidore Stanislas Helman (1743-1806?), whose interest in the Franco-Chinese artistic undertakings of Bertin was well known, and who certified that they had been left with him in 1785 and in April 1789 (AN, F/17/1231, d. 4, F/17/1269 and Tuetey L., 1912, t. I, p. 54 and 60). Desvoyes' research led to the discovery of nearly 250 articles in Paris. They were then deposited at the Muséum national on rue de Beaune, also known as the Nesle depository (dépôt de Nesle), where they were inventoried in April 1794 (AN, F/17/ 372, pp. 18-20, F/17/1072, d. 5, F/17/1188). It should be noted that when an inventory was made of the furniture in the château de Chatou in the autumn of 1794, after the execution of the Marquise de Feuquières, there was no indication that items belonged to Bertin (Curmer A., 1919, p. 184-185).

The annotations made in the registry of the Nesle depot (F/17/372) show the distribution of the remaining objects: 109 items consisting of manuscript and printed books and paintings were intended for the Bibliothèque nationale; 40, consisting of minerals, for the dépôt des Mines (see on this specific subject Laboulais I., 2013, p. 183); of the 161 items consisting of objects or works of art, a large part was intended for the Muséum d’histoire naturelle, the Muséum des antiquités, or the Bibliothèque nationale. Manuscripts and printed books, paintings and other figurative documents were transferred to the Bibliothèque nationale in 1794 and April 1796, where they were divided between the département des Manuscrits and the cabinet des Estampes (BnF, Estampes, Réserve, Y E-1 (1797-1808) – PET FOL, parts 397-399, 401, 402; Tuetey L., 1912, t. I, p. 87, Balayé S., 1988, p. 420, Monnet N., 2014a, p. 144, Cohen M. (online). In September 1796, 97 objects or works of art were transferred to the cabinet or Muséum des Antiques, an ethnographic conservatory established above the cabinet des Médailles (Hamy E. T., 1890, p. 29, 83-86). (On the fate of Chinese collections, see also Finlay J., 2020, p. 148-149.)

In 1811, the Parisian bookseller Antoine Nepveu published La Chine en miniature, ou choix de costumes, arts et métiers de cet empire, représentés par 74 gravures [...], by Jean-Baptiste Breton de la Martinière, a work whose preface lays out its essential material as Bertin's collection of "about 400 original drawings made in Peking, of the arts and crafts of China", "chance" having provided Nepveu with the opportunity to acquire it almost entirely, along with the correspondence between Bertin and the missionaries Ko and Yang (Breton de la Martinière J.-B., 1811, p. XXI-XXII). In this way, elements of the collection that probably disappeared during the first years of the Revolution resurfaced. A number of pieces from Bertin's collection also joined the département des Estampes through a purchase at the Delatour sale in 1810, as well as through a purchase from Nepveu (Balayé S., 1988, p. 421, n 374; Guibert J., 1926, p. 126, 236; BnF, Estampes, Réserve, Y E-1 (1797-1808) – PET FOL, parts 400-401).

During the first decades of the 19th century, parts of Bertin's collections reappeared at several public sales. The first and major one, which took place on February 1815, was mainly composed of objects (169 lots representing around 500 items). The results of this sale are unfortunately not known. According to the catalogue (Notice des articles curieux composant le cabinet chinois de feu M. Bertin. Paris: Imprimerie de Crapelet, 1815), which is certainly inaccurate on this point, the collection consisted of Bertin's entire Chinese cabinet, complemented by some Persian objects. In April 1828, a sale at the behest of Auguste Nicolas Nepveu brought together Chinese and Japanese paintings, lacquerware, porcelain, and other objects from China, notably from Bertin's cabinet. In March 1832, the sale of the Théodore Moreau collection also brought together books, manuscripts, and objects of Chinese and Japanese origin, notably from the Bertin collection. Undoubtedly, Jean Huzard (1735-1838), director of the Alfort School (Huard P., Wong M., 1966, p. 142-143, n. 5, p. 158), and Chrétien Louis Joseph de Guignes (1759-1845), among many others, also owned fragments of the collection during these years.

In June 1830, Nepveu sold Bertin's correspondence with the Beijing missionaries as well as with Ko and Yang to Baron Benjamin Delessert (1773-1847). In 1874, they were bequeathed to the library of the Institut by Baron François Marie Delessert (1780-1868) [BIF, Ms. 1515-1526; Huard P., Wong M., 1966, p. 142, no. 5; Bienaimé C., Michel P., 2014, p. 164-165). The papers of Bréquigny, who was the successor to Abbé Batteux at the head of the Mémoires concernant les Chinois, were bequeathed to his collaborator La Porte du Theil. These papers entered the département des Manuscrits of the Bibliothèque nationale after the latter’s death in 1815 (see Dehergne J. [1983], who describes the dispersal of the documentation used in the Mémoires, and Silvestre de Sacy J. [1970], p. 170).

In 1880, objects that had been attributed to the Muséum des antiques at the Bibliothèque nationale in 1796, possibly complemented by others, were handed over to the musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro, predecessor of the musée de l’Homme (Hamy E. T., 1890, p.29). Alongside the large collections now kept in the Bibliothèque nationale and the Bibliothèque de l’Institut, a large number of objects and especially books and illustrated documents can still be found in public collections. We can note, for example, the manuscripts and albums representing animals and vegetables kept by the Muséum d’histoire naturelle (cited by Huard P., Wong M., 1966, p. 158, 224, 225), or the manuscripts on the fabrication of porcelain and on Chinese vases kept notably by the libraries of the manufacture nationale de Sèvres and of the INHA, cited by Huard P. and Wong M. (1966, p. 226) and Kee Il Choi Jr (2018).

Related articles

Personne / personne

Collection / collection d'une personne