SAINT-SAUVEUR madame de (EN)

Biographical article

According to baptism records from Saint-Eustache in Paris, Madeleine-Suzanne Goullet de Rugy was born on 22nd July 1720 (AN, MC/ET/LXXXIV/548). As is fairly typical when researching eighteenth-century women, no documentation has been found detailing her life from when she was born until she was married on 1st March 1743 to Jean-Anne de Grégoire, later the Marquis de Saint-Sauveur, who had been resident at the Petite Écurie at Versailles since 1721 (AN, MC/ET/XCII/622). He, along with his family, had strong connections at the court of Versailles. The marriage contract drawn up on the 17th and 18th February 1743 is testament to the status of the couple and their respective families, with a dower (douaire) of 200 000 livres, and mention of the « presence et de l’agrément »of Louis XV, Queen Marie Leszczyńska, the Dauphin Louis and the Mesdames Henriette Anne and Marie Adelaide (AN, MC/ET/I/411). Amongst the witnesses at the wedding was Henri Camille, Marquis de Beringhen, an enthusiastic patron of contemporary artists, including Nicolas Lancret, François Boucher and Jean-Baptiste Oudry, listed as a friend of Jean-Anne de Grégoire. However, despite this connection, the Marquis de Saint-Sauveur appears to have shown no interest in acquiring art himself: the posthumous inventories taken in November and December 1751 following his sudden death from apoplexy mention only a few decorative paintings and prints(Luynes 1860-5, vol. 11, p. 274; AN, MC/ET/XXIX/489). Madame de Saint-Sauveur and her husband had three children: Louise Jeanne Marguerite Grégoire de Saint-Sauveur (1745-c. 1816), Jean Baptiste Amédée (1746-?) and Hyacinthe Philémon Louis (1749-1778).

Madeleine-Suzanne held a prominent position at Versailles as the third sous-gouvernante des enfants de France, to which she was appointed by Louis XV on 24 March 1751 (AN, O/1/95, fol. 75) ; LUYNES 1860-5, vol. 11, p. 89). Her retirement from this position was authorised by the King on 13 February 1768, citing poor health as preventing her from continuing her duties (AN, O/1/113, fol. 69). At some point between then and 1771, she took up residency in Paris at the convent, Dames Religieuses de Bellechasse, on the corner of Rue Bellechasse and Rue Saint Dominique (AN, MC/ET/LXXXIV/526). It was not unusual for unmarried or widowed noblewomen to live in the secular quarters of Parisian convents – Mademoiselle Julie de Lespinasse also lived at Bellechasse, and the salonnière Madame du Deffand lived at the Filles de Saint-Joseph de la Providence, also on Rue Saint-Dominique (Asse E., 1877, p. 23, p. 53). This relocation was a significant move, as it placed her in the heart of Parisian society and nearby salons which she would frequent: ‘Madame de Saint-Sauveur’ is recorded on more than one occasion in the diaries of Horace Walpole from 1775 in relation to dinners hosted by Madame du Deffand (Walpole H., ed. 1937-83, vol. 7, p. 344, p. 347, 23 August and 6 September 1775). Madeleine-Suzanne died 4th May 1777 in Paris, with her death announced in the Gazette de France and the Mercure de France, and she was buried at Saint-Sulpice in Paris (AN, MC/ET/LXXXIV/548 ; Gazette de France, Monday 19 May 1777, p. 186 ; Mercure de France, June 1777, pp. 212-3).

The collection

Sources for the Collection

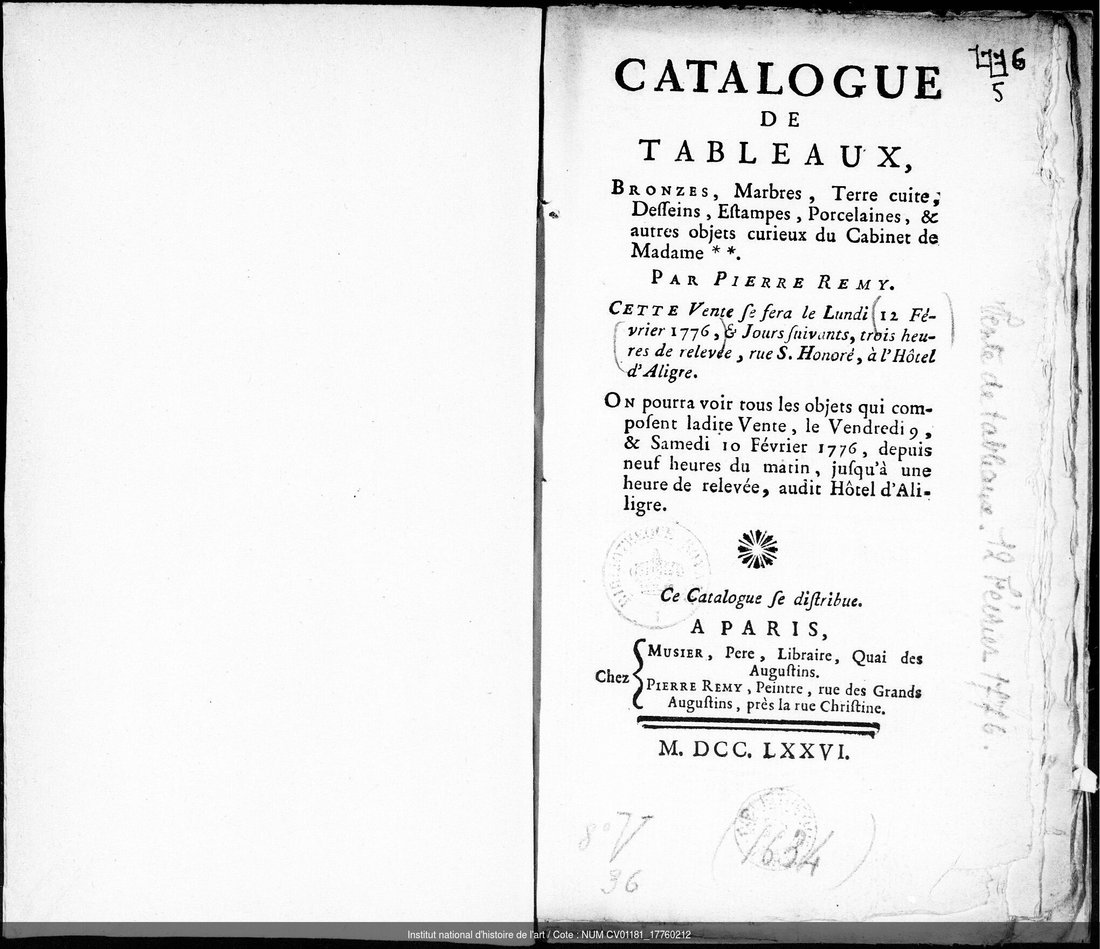

The collection of Madame de Saint-Sauveur is known primarily from the catalogue of her sale, which took place on 12th February 1776, overseen by Pierre Rémy (c. 1715-1797). Unfortunately, there was no inventory taken of Madeleine-Suzanne’s estate, a point mentioned by the commissaire in the scellés après décès taken following her death (AN, Y//14562). The scellés document mentions eight undescribed painting in gilt frames, which is perhaps evidence of a wider collection as the commissaire only documented the most valuable possessions. As the sale of Madame de Saint-Sauveur’s collection (in 1776) took place a year before the death of Madeleine-Suzanne (in 1777), this would also explain why the paintings in the scellés do not include what could be considered the highlights of the sale.

Provenance and Acquisition of the Collection

Like many (though by no means all) women collectors, she had benefitted financially from the deaths of her husband in 1751, and her father in 1754, as an only child and sole heir. Her Succession document valued the estate at her death at almost one million livres, and the first article listed is a large sum of cash (118,813 livres) (AN, MC/ET/LXXXIV/549). Through tracing the provenances of the identifiable works in the sales catalogue, it seems the bulk of known purchases took place in the early 1770s, which coincides with Madeleine-Suzanne’s relocation to Paris from Versailles. Several works were obtained on the secondary market, after being purchased at auction by dealers such as Vincent Donjeux (lot #10, a landscape with figures attributed to Jan van der Heyden and Adriaen van de Velde, was purchased by Vincent Donjeux at a sale on 19 July 1773 for 1105 livres). Three paintings by Louis de Boullogne – a Venus at her toilette, and two ‘Fables’ (lots #41 and #42) – were said to have come from the collection of the Comtesse de Verrue. Although Verrue was an avid collector and patron of the Boullogne brothers, there was no Venus at her Toilette included in Verrue’s sale, and due to the anonymity of works in her inventory, it is not easy to determine if this claim is correct or simply a marketing strategy by the auctioneer (see Catalogue des tableaux de feue madame la Comtesse de Verrue[…], 27 March 1737). The earliest known provenance is of a small work on bronze depicting the Rape of Europa by Il Borgognone in the style of Claude Lorrain; it was purchased from Madame Hayes’ sale on 18 December 1766 by Caulet before entering Saint-Sauveur’s collection. For some important works, such as An Elegant Couple Singing by Candlelight by Nicolas Lancret (circa 1743; private collection), and L’Abreuvoir by Jean-Honoré Fragonard (circa 1763-1765; Musée des Beaux-Arts, Lyon, inv. 2013.3.2), Madame de Saint-Sauveur is the earliest known owner, which opens the possibility that she commissioned works directly and engaged in patronage activities.

Paintings and Drawings in the Collection

Most notably in the collection of paintings listed in the catalogue is the overwhelming predominance of works from the French, Dutch and Flemish schools. From the 105 paintings, only five of the attributed works were from the Italian school, compared to thirty-eight of the Northern and thirty-four of the French schools. The vast majority of these works were genre scenes, followed by landscapes, historical depictions from the Old and New Testaments, and mythological and allegorical works. This certainly conforms to what we know of contemporary fashionable collecting tastes. One striking example which can be identified from the sale catalogue description is The Farmhouse by Jan Wijnants (circa 1655-1684, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam). Also included in the collection were 230 drawings, including several by François Boucher. Additionally, over 400 engravings were listed in the catalogue, in several cases compensating for ‘absences’ of artists popular with collectors in the 1760s and 1770s when this collection was formed, such as engravings by Flipart after Greuze’s Filial Piety and l’Accordée de Village (lots #140 and #141), as well as L’Aveugle Trompé, the work which earned Greuze a position as an agrée at the Académie in 1755, and was engraved by Laurent Cars (lot #142).

Asiatic Objects in the Collection

Although Chinese and Japanese art pieces played a comparatively minor role in the collection, what is noteworthy is that they formed the bulk of porcelain and furniture pieces included in the sale; a testament to Madame de Saint-Sauveur’s taste for chinoiserie, as well as the popularity of such works on the secondary market. Included in the collection were three lots specified as Japanese porcelain: two goblets and saucers with a craquelure finish; two bottles with reliefs; and an antique white Japanese porcelain vase adorned with gilt bronze ormolu additions, highlighting a melange between East and West. Four other bowls are not mentioned as coming from the East, but with adornments of dragons and flowers show at least a chinoiserie style. The four lots of furniture included in the sale are all of antique lacquer, two of which are specified as being antique Chinese lacquer: two desks (secrétaires) with dragons and gilt bronze, and a mantelpiece decoration (garniture de cheminée) composed of six vases of Chinese lacquer.

Related articles

Collection / collection d'une personne

Personne / personne