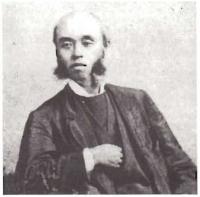

WAKAI Kenzaburō (EN)

Biographical article

Wakai Kenzaburō (若井兼三郎) was without a doubt one of the most influential figures in Japoniste circles of fin-de-siècle Paris. Yet he is an elusive character, often hidden in the footnotes of texts about more glamorous collectors. Wakai’s privacy, alongside his reliance on translators during his time in Europe probably contributed as much to his current obscurity as the fact that he chose to return to Japan permanently in the late 1880s, at a time when others in the same business reached the apex of their careers.

Wakai was born in Tokyo in 1834, shortly before the Meiji revolution would significantly alter quotidian life in Japan. It seems that his family operated a pawnshop in Asakusa at the time, and this early exposure to trade likely influenced Wakai’s membership in the Private Guild of Brokers as a curio dealer (van Dam P., 1985, p. 35).

The years of Wakai’s youth were marked by the new Meiji government’s efforts to enter a global diplomatic stage dominated by Western states, competing for supremacy at grand international exhibitions. In 1873 Wakai joined this competitive industry when he travelled to the Vienna World's Fair as part of Sano Tsunetami’s (佐野常民;1822–1902) exposition delegation. Sano urged the Japanese government to catch up with international practices by setting up trade companies specialising in the export of Japanese commodities (van Dam P., 1985, p. 36). After the end of the 1873 exhibition, the need for a specialised company dealing with export wares became particularly compelling when the Japanese government was faced with a purchasing offer of its entire exhibition pavilion by the London-based Alexandra Palace Company. In response to Sano’s reports and the offer from London, the Japanese government appointed tea merchant Matsuo Gisuke (松尾儀助; 1837-1902) and Wakai Kenzaburo to handle the offer (Guth C., 1993, p. 36f.; van Dam P., 1985, p. 36.). Under the auspices of the official Japanese exhibition bureau (Hakurankai Jimukyoku), the two men founded the Kiritsu Kōshō Kaisha (translated as “The First Japanese Manufacturing and Trading Co.”) in 1874 (Harris J., 2012, p. 155).

Wakai celebrated his first major success at the Kiritsu Kōshō Kaisha with the 1876 Centennial Exhibition held in Philadelphia. Besides the official Japanese pavilion, a handful of private French collectors and Wakai exhibited objects from their own collections. On this occasion, American industrialist and art collector William Walters (1820–1894) noticed Wakai and purchased several pieces, primarily tea wares and other ceramics, from him. It is also possible that Walters consulted Wakai, among others, regarding Japanese acquisitions from other sellers, too (Sakamoto H., 2006, p. 14).

Walters would not forget this positive experience. And at the 1878 Paris Exposition Universelle he purchased a variety of Japanese lacquers, metalwork, and a generous number of ceramics from Wakai and others (Johnston W., 1999, p. 76). Besides their lucrative trade in Japanese antiques, Wakai and the Kiritsu Kōshō Kaisha also operated workshops for contemporary Japanese artists and artisans and supported them in the exhibition and sale of their pieces (Weston V., 2019, p. 25). Suzuki Chōkichi (1848-1919), a notable example, was a member of the company himself and became famous for his bronze incense burners adorned with birds of prey. After Suzuki’s triumphs at the Philadelphia exhibition, Wakai and the Kiritsu Kōshō Kaisha began planning his next project straight away. The result was presented in Paris in 1878 to an awed audience. Today Sukuzi’s 1878 incense burner is part of the V&A’s collection of Japanese art (Weston V., 2019, p. 26).

Once again, Wakai exhibited objects from his personal collection at the Exposition Universelle, the only Japanese to do so (Imai Y., 2004, p. 11). His selection, however, did not find broad appeal. The ceramics’ sober aesthetic did not correspond to European tastes. Art critic Philippe Burty (1830–1890) even lamented that Wakai was too caught up in Japanese traditions and therefore failed to see that the irregular and indented pottery would be unpopular (Burty P., 1889, p. 210). In addition, Ernest Chesneau (1833-1890) complained that the display was a “jumple” (pêle-mêle) and that objects were inadequately labelled (Chesneau E., 1878, p. 842). On the other hand, Wakai’s expertise and knowledge of Japanese art were praised by curator Paul Gasnault (1828-1898), who noted the high quality of labels Wakai had prepared for Emile Vial’s (1833-1917) collection at the exposition (Gausnault P., 1878, p. 910f.).

This early experience with negative reviews probably made Wakai aware of the importance of catering to local tastes if the Kiritsu Kōshō Kaisha was to be successful in its mission to popularise Japanese arts and crafts abroad. Yet the failing company refused to address criticism and, as a consequence, Wakai and his young colleague and interpreter Hayashi Tadamasa (林忠正; 1853–1906) finally decided to leave in 1882, and after a brief stint at the Mitsui Bussan company branch office in Paris, they went into business together for themselves (Koyama-Richard B., 1997, p. 240).

The business partners set out to establish a strong reputation in the field of Japanese art in fin-de-siècle France. In 1883 alone, Wakai was involved in two major exhibitions of Japanese art in Paris. The Exposition rétrospective de l'art japonais, organised by Louis Gonse (1846-1921), took place at the Galerie Georges Petit from April to May 1883 with contributions by Wakai and the Kiritsu Kōshō Kaisha (Gonse L., 1883). Around the same time, Wakai, together with collector and publisher of Le japon artistique, Siegfried Bing (1838-1905), and the Ryūchikai company, which promoted Japanese art abroad, co-organised the first Salon annuel des peintres japonais. A letter sent by Wakai to the Ryūchikai considers possible exhibition locations and works to be included. In early April, Wakai travelled to Japan to examine the exhibits and return them to Paris for the display (Kigi Y., 1987, p. 64). In October of the same year, the first edition of Gonse’s seminal two volume L’art japonais frequently mentioned Wakai and Hayashi and acknowledged a deep indebtedness to Wakai’s five volume work “Fouso Gouafou” – (扶桑画譜, lit. “Japanese picture book”), which Hayashi had translated, but which was never published (Gonse L., 1883 Vol. I, p. 157).

At last, in December 1883, the Société Wakai-Hayashi was founded. The company probably started trading in late 1883 or early 1884, although it only appeared in the Annuaire du commerce from 1885 (p. 714). An exhibition of Wakai’s antique kakemono in London in 1885 was one of the new company’s early projects. The following year Hayashi took the London exhibition to New York, where the press controversially referred to Wakai as “art advisor of his Imperial Majesty the Mikado” (London and China Express, 1887, p. 18; St James’s Gazette, 1885, p. 14).

It is difficult to ascertain what caused the end of Hayashi and Wakai’s joint enterprise, but it has been suggested that Hayashi might have refused to marry Wakai’s daughter around 1886, when the two split (Koyama-Richard B., 1997, p. 243). A letter sent to their customers in 1889, however, informed collectors of Wakai’s retirement, suggesting a more amicable departure (Emery E., 2022). After the break, Wakai permanently returned to Japan, where he became one of the main suppliers to collector Kawasaki Shōzō (1837–1912) in Kyoto (van Dam P., 1985, p. 37). Wakai must have continued to remain active in exhibiting Japanese art, because he appeared as an exhibitor in the official catalogue of the Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition (World's Columbian Exposition, 1893: Official Catalogue,1893, p. 103, 303).

Towards the end of his life, Wakai spent some time working in Kyoto, where wealthy industrialist Kawasaki Shōzō (川崎 正蔵;1837–1912) was among his clients (van Dam P., 1985, p. 37). Eventually he returned to his native Tokyo, where his name appeared in 1899 the records of Masuda Takashi’s (益田孝; 1848–1938) Daishi kai, an annual tea gathering founded to honour the Buddhist monk, calligrapher, and poet Kōbō Daishi (弘法大師; 774-835) (Guth C., 1993, p. 8, 112.). Industrialist and collector Masuda also purchased a 13th-century Chinse Zen painting art from Wakai around 1890 (van Dam P., 1985, p. 37).

Unfortunately, nothing is known about Wakai’s last years, except for his date of death on 22 December 1908 and the location of his grave in Yana Cemetery, Tokyo.

Wakai’s seal: a guarantee for quality

The scarcity of historical records originating directly with Wakai himself makes it difficult to delineate his personal collection from the items he acquired for commercial purposes. However, the wealth of ukiyo-e prints that bear his characteristic red collector’s seal reading “Wakai Oyaji” (わか井をやぢ) in museum collections around the world are a testament to his significance. Although this reveals little about the person Wakai, the trader’s broad presence in valuable collections illustrates the weight his opinion and taste carried among his contemporary Japanophile scholars, amateurs, and collectors.

Around 1885 the European and American press began referring to Wakai as the “art advisor of his Imperial Majesty the Mikado” (Emery E., 2021, p. 63). Although this claim did end up at the centre of a dispute between American and European japonistes in the press and Hayashi eventually had to retract it, even this brief and tenuous association with the emperor reflected the high esteem in which global Japoniste circles held Wakai (Emery E., 2021, p. 63; Emery E., 2022.). This esteem was further reflected in the appreciation and gratitude expressed towards Wakai by a multitude of French, British, and American collectors. Gonse’s appreciation for Wakai ran like a thread through L’art japonais. (Falize, 1883, p. 208; Gonse, L. 1883 Vol. I, p. IV, 157f.). William Anderson (1842–1900), a British scholar and collector of Japanese art, too, singled out Wakai and Hayashi and thanked them for the “invaluable services” to European collecting (Anderson, W., 1886, p. VIII). And Bing had also relied on Wakai to attain his status as an expert on Japanese ceramics (Gonse L., 1883 Vol II., p. 244). We also know that the American suffragist and collector Louisine Havemeyer (1855-1929) sought out Wakai’s seal as a testament of quality (Frelinghuysen A., 1993, p. 135). Collector Ernest Hart (1835–1898) also praised Wakai as “the most accomplished Art expert in Japan” (Hart E., 1895, p. 339; Hart E., 1896).

Finding a place for Japanese art

During the fin-de-siècle the meaning and function of Japanese art was in constant flux. It could function as a tool for diplomacy or economic advancement for the new Meiji government. Appalled at the unfavourable depiction of Japan – merely a curiosity – at early international exhibitions, the Japanese government and the nation’s elites sought to enter the realm of fine art, and to escape ethnographic or anthropological classification. This endeavour proved ambivalent as the European appetite for cheap mass-produced prints initially baffled the Japanese establishment, who hoped to use exhibitions to demonstrate new and “progressive” art (Foxwell C., 2009, p.41). It was only possible for Gonse to ascertain that pieces by Kanō Tsunenobu (狩野常信; 1636-1713) and Rembrandt were equal in artistic value through the groundwork laid by Wakai and his peers (Gonse L., 1883, Vol. II, p. 228).

Yet elevating Japanese culture into the realm of fine art also carried risks. Now that Japan had become a knowable place with art to be appraised, studied, and taught by experts, a struggle over the authority to tell Japanese (art) history ensued. While Wakai stressed the importance of China’s influence in all branches of Japanese culture, ambitious (Western) scholars and pundits like the American Ernest Fenollosa (1853-1908) and Anderson increasingly turned to nationalist interpretations of Japanese art (Burty P., 1884, p. 386f.; Emery E., 2021, p. 61). Fenollosa, in particular, did not shy away from publicly denouncing Wakai and Hayashi, criticising their choice of collections and accusing them of profiting from the gullibility of their Western buyers (Emery E., 2021, p. 67; Fenollosa 1885; Kigi Y., 1987, p. 87). Ultimately, Fenollosa’s efforts to dominate the field were effective and Wakai’s name, so frequently mentioned in the first edition of Gonse’s L’art japonais no longer appeared in the 1885 edition (Kigi Y., 1987, p. 87). After his return to Japan, Wakai and his influence have increasingly been neglected, but perhaps the time to recognise his vital role in establishing Japanese art globally has finally arrived.

Related articles

Personne / personne