BING Siegfried (EN)

Biographical article

As a member of the extensive Bing family, with relatives and stores in Hamburg, Germany and Paris, France, Siegfried Bing (1838-1905) was trained early on in the making and marketing of porcelains. Whether he studied Asian art in the 1850s is not known; he did however become aware of Chinese and Japanese art works in Paris during the 1850s (Bing D., 2017, p. 135-153). By the late 1860s, during the Second Empire (1852-1870), objects secured by Bing from numerous locations were found in his Parisian shops on the rue de Provence, rue Bleue, rue de la Paix et rue Chauchat (see addresses above) to which they attracted an ever-growing clientele. Some of the objects sold by Bing were perhaps exhibited in the Musée Oriental in Paris in 1869, but none of the objects exhibited in the show came directly from Bing’s shop or his personal collection. (Jacquemart A., 1869). This exhibition was among the first to sponsor Japanese art in this city.

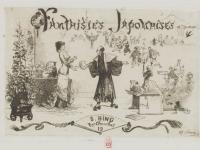

After the Paris World’s Fair of 1867, an increasing interest in Japanese art developed. (Lacambre G., 1980, pp. 43-55, 2018, pp. 43-55). But the real enthusiasm for Japanese art followed the Exposition Universelle of 1878 in Paris just when Bing was becoming the foremost promoter of Japanese art. Listed in the Didot-Bottin, Bing’s shops were found, at first, under the categories such as “Curiosités, Bing (S) articles de Chine et du Japon, Chinoiseries and Japoneries”, and at several different addresses. (Didot-Bottin 1864-1900). He also began to keep the best objects he found for himself; amassing over time a staggering collection (Collection S. Bing, 1906) which he kept in his apartment 9 rue Vézelay in Paris. It was at this location that selected connoisseurs were admitted so that they could study some of the best of Bing’s objects in the quiet of his home as well as learn from him about Japanese art and share with him their own knowledge.

During the 1870s, Japanese art objects were being sold in increasing numbers of shops in Paris, Bing as well as others found themselves in great demand. He also became the expert in many public sales. For example, in his introduction to the sale of the Burty collection, Bing wrote that “Dans la collection que sa mort nous livre, Burty apparait vivant. Parmi ces choses il n’en est pas une qui ne parle d’une sensation éprouvée, profonde, vibrante, comme en connaissent seules les natures exquisement affinées.” Writing about the increased number of works arriving from Japan which were often “singuliers mélanges, … “Burty n’était pas de ceux qui ont besoin de passer par une “école” pour savoir discerner le grain au milieu de l’ivraie.” (Bing S., 1891) This activity he continued over the next twenty-five years becoming the chief spokesman for Japanese art in Paris as he organized some of the largest sales of private collections, and many exhibitions (Goncourt Edmond 1897). In order to build his stock of Japanese art work Bing thought it necessary to travel to Japan (1880-1881) where he could first hand learn about collectors willing to sell their collections and set up trade connections with Japanese dealers who could supply him with objects for his growing business in Paris. He travelled to Japan, China, and India with his brother Auguste (1852-1918) who, after Bing returned to Paris, remained in Japan with his family to take care of the business in Japan. (Weisberg G., 1986 and 2004, and Bing D., 2017). In 1883, when Louis Gonse (1846-1921) organized a huge show in Paris on Japanese Art it was accompanied by a detailed catalogue. The Collection M.S. Bing was prominently represented with 659 works (Gonse L., 1883). Bing’s interest in all types of Japanese art work led him to promote the Salon Annuel des Peintres Japonais. (Bing S., 1883 and 1884).

Beyond all the exhibitions and auction sales Bing organized to assure his position as the key spokesman for Japanese art, Bing became the purveyor of Japanese art for many museums in Europe including the Kunst und Gewerbe in Hamburg where the Director of the Museum Justus Brinckmann (1843-1915) was a fervent supporter of Japanese art and Bing. As he did so, Bing’s position grew internationally. He sold art objects to museums throughout Europe as the demand for these objects increased. Bing sold objects to Museums in Austria such as Vienna and Graz, to several German museums beyond Hamburg such as Krefeld, Nuremburg and others. He also sold objects in Norway, in Sweden, Finland, in England to the Victoria and Albert Museum, to the United States, and to French Museums, thus establishing his place as one of the primary promoters of Japanese art in the world. He also often organized touring exhibitions of Japanese art in many cities where he sold objects in this way making more people aware of what he had in stock. This was the case for example with the Museum in Leipzig in Germany (Weisberg G., 2004, p. 60-71 and Weisberg G., 2005).

As members of the first generation of collectors of Japanese art passed away, Bing was also called upon to organize sales with catalogues that established the importance of these collections and attracted buyers in greater numbers. Many of the objects were sold not only to other collectors, but also to museums around the world, thus expanding the fame of Japanese art. One of the sales that Bing was responsible for was that of the collection of Philippe Burty (1830-1890) (Bing S., 1891). It was only one among many others for which Bing’s expertise was sought after. Another was the sale of the Goncourt collection which Bing organized and for which he prepared the catalogue (Bing S., 1897).

Toward the end of the 1880s, in order to establish his reputation not only as a merchant of Japanese art, but also as a true connoisseur of Japanese art, Bing decided to publish a magazine dedicated to the history Japanese art. Known as Le Japon Artistique the magazine appeared every month for three years, from 1888 to 1891, or thirty-six separate issues in French, English, and German. Articles were authored by the leading Japonistes of the day on wide ranging topics from ceramics, painting, the decorative arts, Japanese prints with many of the illustrations drawn from Bing’s own collection (or for sale in his shops). This magazine, illustrated with many color images, helped further in the popularization of Japanese art and Japonisme among a large public in Europe and America (Weisberg G., 1986, p. 6-19 and Weisberg G., 2004, p. 52-70). Not only interested in Japanese art and not content to be only a dealer of Japanese art, Bing became fascinated by the development of modern decorative art. This led him to initiate contacts with artists, painters, and those committed to design issues in the crafts (Weisberg G, 1986, 2004). Among the many French and international artists who attracted Bing’s interest was the Belgian designer Henry van de Velde (1863-1957) he gave commissions to create furniture in the 1890s. Thus, van de Velde, among other artists, collectors, writers, had the chance to study the best quality Japanese prints in Bing’s home on rue Vézelay, and to share his ideas with likeminded enthusiasts not only of Japanese prints, but also of other Japanese artistic production. In December 1895, when Bing opened his newly renovated galleries at 22 rue de Provence to modern artists in all areas, a part of his building, at rue Chauchat, had a separate entrance where a visitor could go in to see and purchase examples of Japanese art. (Weisberg G, 1986, p. 60) He maintained the distinction between the space dedicated to Japanese art and his Gallery of Art Nouveau until he had to give up the business in 1904 because of ill health. At the time of the Paris World’s Fair (1900) Bing, replacing Tadamasa Hayashi who was ill, was appointed by the government to a commission whose purpose was to assess the genuineness of the Japanese ceramics that were put on display. (Weisberg G. 1986, p. 172) This honor suggests that Bing had important contacts in the French government; furthermore, Bing was also given the right to construct his personal pavilion of art nouveau on the Fair grounds. (Weisberg G. 1986, p. 172-179)

While he carried on with the advancement of his Art Nouveau Gallery, Bing continued to hold exhibitions of Japanese art at his shop as well as amassing a monumental personal collection that was sold at public auction after his death in 1905. This sale led to the appearance of beautifully illustrated catalogues that provided an exhaustive record of what had been in Bing’s collection and what was up for sale, a large number of examples in many categories were reproduced. (Galerie Durand-Ruel, Paris, may 1906). After viewing the collection Gabriel Mourey wrote an article on Bing and the collection in Gil Blas, which was reproduced in part in L’Art Moderne, (Mourey G. 1906) He stated that: “A la suite d’une série d’opérations chirurgicales particulièrement graves, il s’était retire l’été dernier sur les hauteurs de Vaucresson, pour achever sa convalescence. J’allai le voir là; je le trouvai changé, très amaigri, enveloppé de châles, sous les arbres, malgré la chaleur, mais plein de vie, de vie spirituelle, la vraie vie. Et nous causâmes longuement, d’art, toujours, des primitifs italiens, des cathédrales gothiques, des estampes japonaises, en quelques mots de toutes les choses qui, seules, rendent l’existence supportable. Font trop brèves les journées, alors que l’on sent tant de trésors de beauté inexplorés, inconnus de soi-même, susceptibles de vous donner de si douces et si enivrantes sensations. Puis il voulut nous montrer quelques pieces reçues la veille d’Asie-Mineure. Il y avait une grande jarre couverte d’émail bleu turquoise, d’un bleu miraculeux et changeant, où se mêlaient les bleus ardents des plumes de paon aux bleus tendres des myosotis,… et Bing s’exaltait, promenait ses mains avec amour sur les amples formes du vase, … . “Est-ce délicieux, disait-il, est-ce délicieux!” Puis, après une pause: “Savez-vous que j’ai faille mourir?... Je le savais, mais la mort ne me faisait pas peur; je songeais à tous les beaux bibelots qui m’ont appartenu, que j’ai aimé, dont j’ai joui, et je trouvais que je n’avais pas le droit de me plaindre de la vie…” While many of the purchasers have not been identified, there were examples from Bing’s collection that were privately secured; many other examples ended up in the collections of various museums. Some examples of the collection remained with his family as Bing’s sole surviving son, Marcel (1875-1920), continued to monitor the collection until his death. In effect, thousands of art objects passed through Siegfried Bing’s shop during his lifetime. Charting these is not feasible. The pieces that remained with Marcel were partially listed in the document produced at the end of Marcel’s life (Dépot judiciaire du testament de M. Bing, 13 Décembre 1920, Testament de M. Lucien Marcel Bing en son vivant, célibataire majeur antiquaire, demeurant à Paris Place de Laborde no. 14, décédé le 28 Octobre 1920. Autre dépôt judiciaire de testament: Me E. Delorme notaire à Paris, rue Auber no. 11). Apparently, nothing of his collection remained intact since the Siegfried Bing family line ended with Marcel Bing.

The collection

Unlike the collections of connoisseurs who nurtured a collection of objects to keep the best ones for themselves until it was disposed of after their death or until they gave it to a museum, the situation with Bing’s collection was different. While Bing also kept some of the best pieces for himself, as a major promoter of Japanese art, as a dealer, he added to his collection, but also sold objects through his various galleries in order to promote the taste for Japanese art among a public eager to form collections themselves. A large part of the collection was evidently housed in his private apartment on rue Vézelay - the location where artists, writers, collectors, museum curators and close friends came to admire what he loved “Ce matin, rue Vézelay, chez Bing qui m’a convoqué ayant reçu du Japon quelques beaux kakémonos et paravents. Ils sont, en effet, très intéressants – Un Kôrin admirable deux échassiers largement peints en blanc, or, et rose d’une simplicité d’une liberté de dessin admirable – Dès que je l’aperçois je reçois le coup de foudre et me dis, in petto, c’est pour moi ! – Un autre kaké de Matabei (3 000) 3 personnages accroupis, très beau, intéressant, mais ne m’emballe pas – un charmant Hokusaï 2 oiseaux s’échappant de dessous une large feuille – etc. – […] Un très grand kaké de […] représentant une courtisane grandeur nature. Il est dans un état de conservation parfait, on le croirait peint d’hier. Mais il me laisse froid malgré ses qualités. Ce serait un beau panneau décoratif pour un musée. Bing en demande 6 000 frs. Quelques beaux paravents dont un à fond d’or éteint, par Yetokou (fin du XVIe), sur lequel sont dessinés des cerfs et biches auprès d’une cascade, sous des arbres aux feuilles roussies. C’est un superbe décor (3 000 fr). C’est une pièce qui me tente, mais il faut être raisonnable… je n’emporte donc que le Kôrin épatant pour 2 500 frs – Impossible d’obtenir la moindre diminution de prix – La collection de Bing est encore bien belle et surtout parfaitement arrangée, il y a cette statue en bronze, extraordinaire, d’une attitude si imprévue si étrange qui nous produisit à tous tant d’effet certains soirs il y a quelques années – nous voulions tous l’acheter à l’insu les uns des autres et c’était comique de nous voir prendre Bing à part dans un coin de son salon et lui dire : n’est-ce pas, ne la vendez pas sans me prévenir – Il prétendait, depuis, en avoir refusé plus de cent mille francs – ce serait à vérifier… Enfin la statue est toujours là, la tête inclinée sur sa main, rêveuse et faisant rêver ! – mais que de vides dans les vitrines et dans toutes les séries – Ce doit être bien dur pour un homme comme Bing que d’être obligé de se séparer de ses plus belle pièces – Les affaires sont dure et l’ « Art nouveau » est dans le marasme et lui mange beaucoup d’argent. Pauvre homme, je le plains sincèrement, et on a été trop souvent injuste pour lui (il a un superbe bol plat Coréen – 2 000 – tout rapiécé). » Journal du 24 janvier 1898 (Silverman W., 2018, p. 109-110).

. A number of these objects (Japanese prints, lacquers, ceramics, sculpture, etc.) were sold in 1906 after Bing’s death in 1905 (Galerie Durand-Ruel, Paris, 1906). The elaborate catalogue divided into sections containing bronzes, paintings, lacquers, sculptures, listed 957 numbers. This, however, is not the sum of what he possessed or secured. Bing held many sales of objects at different moments in his career as a dealer and collector such as the sale of Chinese porcelains, jades, bronzes, etc., in New York at the Moore’s Art Galleries in 1887 (Moore’s Art Galleries, New York, 1887) or the sale of Japanese prints in 1894 also in New York at the American Art Galleries that comprised 290 individual prints and albums (American Art Galleries, New York, February 1894). He also made sure that objects he possessed were exhibited at various museums over the course of his life helping in the promotion of Japan throughout Europe. The best that can be said about Bing as a collector, is that his collection was never stationary. It was always changing, subject to sales, changes in taste, and availability. Bing’s collection was vast, and what it included can never be completely documented because of its changeability. As a dealer of Japanese and Chinese art, and the promoter of a new decorative style under the name of Art Nouveau, Bing often needed funds to support his activities. This changeability makes his collection a type of living organism.Those who were able to see what he possessed could seldom be sure that what he owned would still be around if they visited him a second or third time at different moments. In this way, Bing’s collection was also a tool, an educational gathering of often disparate objects, that drew collectors to him while advancing the cause of Japonisme around the world.

Related articles

Personne / collectivité

Personne / collectivité

Personne / collectivité

Personne / personne