TISSOT James (EN)

The Artist’s Beginnings

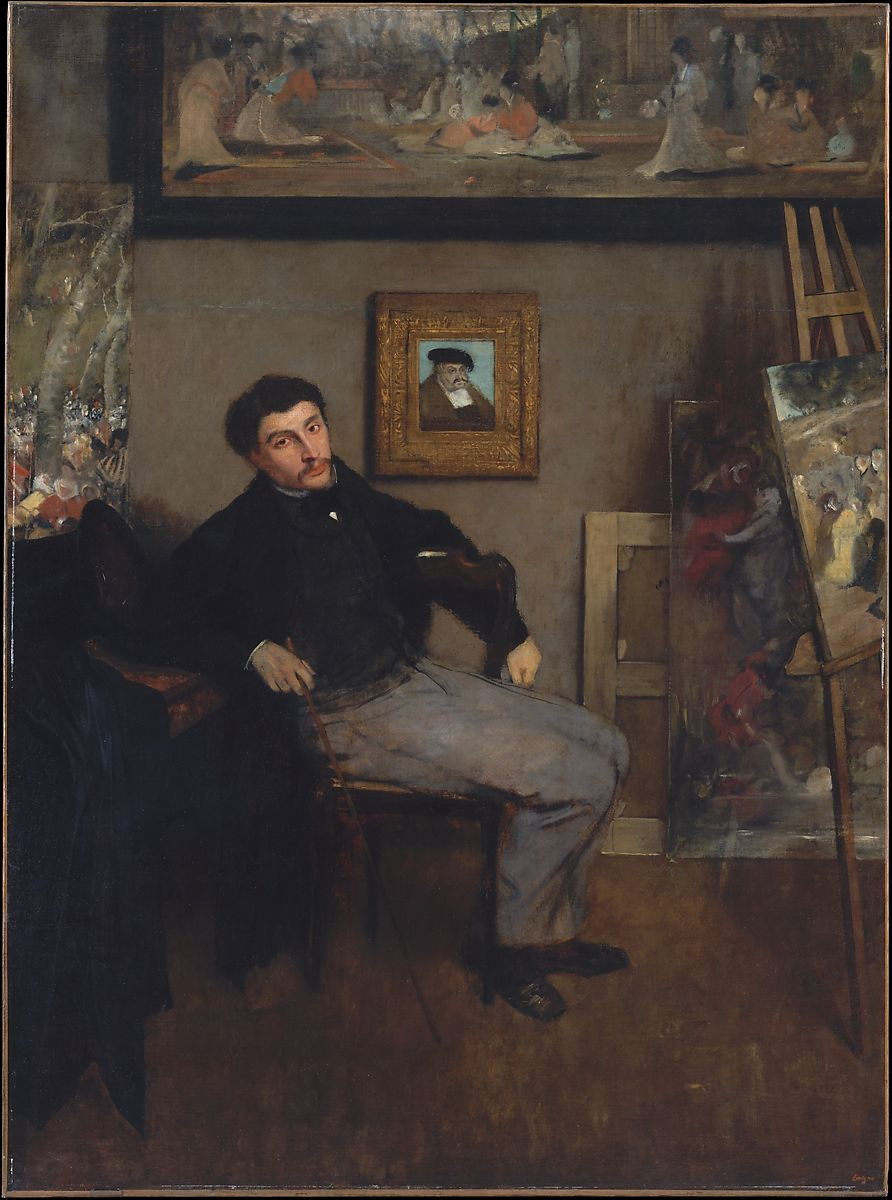

Jacques-Joseph Tissot was born on October 15, 1836 in Nantes. He was the second of four sons of Marcel-Théodore Tissot (1807-1888), a prosperous fashion merchant of Franche-Comté origin, and Marie Durand (1803-1861), a milliner of Breton origin: the familiarity of the future artist with the world of fashion and fabrics would be felt later in the great care taken in the representation of fabrics and feminine grooming in his paintings, pastels, and engravings. Jacques-Joseph adopted the first name James in 1847 (Kisiel M., 2020, p. 267). After studying at the Jesuit collèges in Brugelette (Flanders), Vannes (Brittany), then Dole (Jura), he moved to Paris around 1856 where he lived in the Latin Quarter and entered the École des Beaux-Arts, working under the direction of Louis Lamothe (1822-1869) and Hippolyte Flandrin (1809-1864) while also working as of 1857 as a copyist at the Louvre (Sciama C., 2005, p. 14-15). It was around this time that he met James Abbott MacNeill Whistler (1834-1903), both of whom copied Ingres' Roger délivrant Angélique at the Musée du Luxembourg (Kisiel M., 2020, p. 21). It was probably Whistler who introduced him to Henri Fantin-Latour (1836-1904) and Alphonse Legros (1837-1911) (Wood C., 1986, p. 21). Tissot also met Edgar Degas (1834-1917) who remained his friend until the 1890s (Buron M., 2019, p. 249). Tissot also knew Henri Leys (1815-1869) whom he visited in 1859 in Antwerp (Kisiel M., 2020, p. 268).

The same year, he had his first exhibition at the Salon: his first five paintings were followed by regular contributions in 1861 and then from 1863 to 1870 (Kisiel M., 2020, p. 268-269). At first, Tissot mainly produced portraits and historical paintings. These paintings, drawing their argument from secular literature –such as Goethe's Faust – or from sacred history, such as the parable of the prodigal son, are played out in a more or less distant past, oscillating between medieval times and evocations of the past century (Sciama C., 2005, p. 13-27). In this sense, the works he sent to the Salon of 1859 are very representative of his artistic beginnings. There are two portraits – Mme T. (location unknown) and Mlle H. de S. (location unknown) – and three canvases of medieval inspiration: Promenade dans la neige (1858, private coll.) and two "wax painting[s]" with religious subject matter, Saint Jacques le Majeur et saint Bernard (location unknown) and Saint Marcel et saint Olivier (location unknown) which may also be a tribute to his family (Matyjaszkiewicz K ., 1985, p. 101). Subsequently, the attribution of Tissot's paintings to a particular pictorial genre becomes less obvious. The artist indeed claims a certain freedom in his artistic practice and tends to blur and hybridise categories, for example by bringing his history paintings closer to genre paintings or his portraits to history paintings, genre scenes, photographs or fashion plates (Kisiel M., 2020, p. 24-25). Although his style was sometimes criticised, between 1861 and 1864 for its archaism and its dependence on Leys (Kisiel M., 2020, p. 30-31), Tissot quickly achieved a certain success: his Rencontre de Faust et Marguerite (1860, Musée d'Orsay, inv. inv. RF 1983 93) presented at the Salon of 1861 was acquired in 1863 by the Musée du Luxembourg, for the sum of 5,000 Fr. (Kisiel M., 2020, p. 284 ). In September 1862, Tissot traveled to Italy and visited Milan, Florence, and Venice. There, he admired the works of Giovanni Bellini (v. 1425-1516), Andrea Mantegna (1431-1506), and Vittore Carpaccio (1455-1525), which inspired him to create two prodigal-son-themed pendants that were transposed to Venice and Flanders (1862 and 1863, Paris, Musée du Petit Palais, inv. PPP4856 and PDUT1453). The year 1862 marked the beginning of Tissot's English adventure: that year, he presented a painting at the London International Exhibition and then, in 1864, exhibited it for the first time at the Royal Academy in London (Kisiel M. , 2020, p. 268). It was around this period that Tissot abandoned the archaic vein for more contemporary themes, some of which illustrate his burgeoning interest in Japanese art – an interest shared in particular with his friends such as Whistler as well as with his father who was also a collector of Chinese and Japanese objects (AD 25, 3E44/465).

Evolution towards Scenes of Modern life

From 1864-1865, Tissot took up new themes in his paintings: this was the time of his first scenes of modern life (Wood C., 1986, p. 31-51). This development earned the artist growing success, and he received a gold medal at the 1866 Salon for Le Confessionnal (1865, Southampton City Art Gallery, inv. Acc. N. 581) (Kisiel M., 2020, p. 296). His comfortable financial situation, due both to his business acumen and his father’s support, enabled him in 1867 to settle into a small hotel particulier that he had built on the brand new avenue de l'Impératrice (now avenue Foch) (AN , MC/ET/XXX/990).

Among his works representing modern life are his large Japanese compositions. From the beginning of the 1860s, Japan began to interest restricted circles of amateurs, such as the brothers Jules (1830-1870) and Edmond (1822-1896) de Goncourt, or even Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867). These first circles of the curious also included a few artists: "It was actually through our painters that the taste for Japanese art took root in Paris, was communicated to amateurs, to people of the world, and consequently imposed on the industries of art” (Chesneau E., 1878, p. 386). Among these pioneers, Tissot, Whistler, and Alfred Stevens (1823-1906) stand out for their early Japanese compositions (Gabet O., 2014, p. 42-49). Around 1863-1864, in The Princess in the Land of Porcelain (Washington, Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution/F1903.91a-b), Whistler thus represented a female figure, dressed in a kimono in an interior decorated with delicate Japanese objects. His friend and rival Tissot (Sciama C., 2005, p. 54) took a different course in 1864 with La Japonaise au bain (Dijon, MBA, inv. inv. 2831 and J167), a canvas that is fairly well known today, although it was neither exhibited nor sold by the artist (Kisiel M., 2020, p. 86): in fact, it was not exhibited until 1958 (Kisiel M., 2020, p. 307). The artist chose to paint a much more seductive-looking woman – one of the rare nudes in his work – to highlight a floral kosode and some Japanese accessories and objects (Kisiel M., 2020, p. 77-78 and 84-86). These are probably objects that Tissot has just acquired from Mme Desoye's boutique located at 220, rue de Rivoli in Paris. The painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882) testifies, in a letter to his mother dated November 12, 1864: "I went to this Japanese shop, but all the costumes had been rounded up by a French artist, Tissot, who, it seems, is in the process of executing three Japanese paintings which the shop owner described to me as three wonders of the world and which, in her opinion, would obviously have eclipsed those of Whistler" (Rossetti D. G., Rossetti, W.M., 1895, p. 180). With Femme tenant des objets japonais (1865 or c. 1870, private coll.), Tissot was no doubt seeking a less fantasised, more "authentic" vision of the "Japanese": the woman's face indeed seems inspired by that of a Japanese doll owned by the artist (Kisiel M., 2020, p. 78), photographed by him in 1868 in Poupée (Chicago, Ryerson Library, Art Institute). The series of three Femmes regardant des objets japonais, presented at the Salon of 1869, is composed respectively of Femmes regardant le temple chinois (private collection), Femmes regardant un navire japonais (Cincinnati Art Museum, inv. 1984.217), and Femmes au paravent (private coll.), according to the titles given by the artist in his accounts (Kisiel M., 2020, p. 286-287). This set still offers a different perception where fashionable women, very Parisian, are admiring various Japanese objects from the Tissot collection, real "trinkets among trinkets" (Kisiel M., 2020, p.86).

It was not until the Universal Exhibition of 1867 that the general public began to take an interest in Japan (Quette, 2018, p. 20-29). It should be noted that this was the first time that this country had its own pavilion (although previous exhibitions presented objects from Western collectors). The Japanese delegation was led by Prince Tokugawa Akitake 徳川 昭武 (1853-1910), brother of the last Tokugawa shogun. The popularity of Tissot, a collector of Japanese art, and the proximity of his home to the residence of Prince Akitake (then located at 53, rue Pergolèse) probably explain why the prince chose this worldly artist, a Japonisant painter, to teach him drawing from March to September 1868 (Ikegami C., 1980, p. 147-156). It was on this occasion that Tissot painted the Portrait de Tokugawa Akitake (Mito, Historical Museum of the Tokugawa Family), which he dedicated to the prince.

The English Years: Scenes of Society, Scenes of Intimacy

During the war between France and Prussia, Tissot joined the sniper company "Tirailleurs de la Seine", which included several artists, from October to December 1870 (Kisiel M., 2020, p.99).

After the episode of the Commune, during which he was an ambulance driver (Kisiel M., 2020, p. 100), Tissot left France in June 1871 to settle in London, first at Cleeve Lodge with his friend Thomas Gibson Bowles (1841-1922), correspondent for the Morning Post during the siege of Paris, and to whom he sent caricatures from 1869 until 1877 for his magazine Vanity Fair (Kisiel M., 2020, p. 102-103). Tissot then moved to the St. John's Wood district, first to 73 Springfield Road in 1872, then to 17 Grove End Road in 1873. He quickly met with great success in England, as testified by Berthe Morisot (1841- 1895) who visited him in 1874 (Matyjaszkiewicz K., 1985, p. 46-47), or, on November 3 of the same year, Edmond de Goncourt (1822-1896) in his Journal (Goncourt E. de, Goncourt J. de, 1989, vol. 2, p. 596).

From 1873, he was a member of the Art Club of Hanover Square where, between 1876 and 1878, he joined Giuseppe De Nittis (1846-1884), a Japanese art enthusiast and mutual friend of Degas (Moscatiello M., 2009, p. 122 and 124).

Tissot's Japonisme underwent a new evolution during these English years (Wentworth M., 1980, p. 127-146). The artist still continued to arrange a few Asian objects more or less discreetly in his works, such as the Chinese porcelain mounted as a lamp in the background of the Portrait de Algernon Moses Marsden (1877, private coll.). However, even when their presence is well marked, as in Le Rouleau japonais (1872-1873, private coll.) or L’Éventail (1875, Hartford, Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, inv. 1982.158), these objects no longer focus the attention with as much ostentation as in previous paintings. The female figures in these canvases are no longer those of the ‘women looking at Japanese objects’, absorbed in their contemplation. Tissot also began to use the aesthetic codes of Japanese art in a more personal way. A canvas he produced around 1878, Kathleen Newton à l’ombrelle (Gray, Baron-Martin Museum, inv. GR-93-723), thus takes up the narrow and vertical format inspired by hashira-e prints, cropped and tight on a frontal foreground or with a background in solid colours, suppressing perspective, typical of Japanese prints (Kisiel M., 2020, p. 81). From a thematic point of view too, this painting is close to bijinga prints, traditionally depicting beautiful women. Finally, the Japanese parasol, which can be found in other works featuring Kathleen Newton, such as Le Hamac (c. 1878-1879, private coll.), was part of the artist's collection: it is found in a later photograph showing Tissot's workshop, in his château de Buillon (AM Besançon, 1964 Ph 22568).

These years were also an opportunity for Tissot to broaden his palette of creative techniques: he was introduced to the technique of cloisonné enamels (Matyjaszkiewicz K., 1985, p. 94-99) and returned to the practice of engraving. Between 1875 and 1885, most of his engravings are reinterpretations with variations of paintings that he may have painted previously; they are nevertheless originals (Matyjaszkiewicz K., 1985, p. 76). The sale of his etchings and drypoints contributed to his success, although criticism of his creations was more mixed as of 1875: two of his works were refused by the Royal Academy, and Tissot lost the support of the art dealer in London, Thomas Agnew & Sons (Kisiel M., 2020, p. 117).

Subsequently, Tissot met Kathleen Newton (1854-1882), a young woman of Irish origin, a divorced mother of two children, who moved in with him around 1877, and with whom he lived more of a "family" existence (Kisiel M., 2020, p. 166). She, her children, nephews, and nieces then became the artists’s favoured models, whom he represented in numerous paintings and engravings, and who inspired his illustrations of Edmond de Goncourt's novel Renée Mauperin (Paris: Charpentier, 1883), until tuberculosis killed the young woman on November 9, 1882. Five days later, Tissot left England and returned to Paris, "very affected" by this loss, as noted in his Journal by Edmond de Goncourt (Goncourt E. de, Goncourt J. de, 1989, vol. 2, p. 966), whom Tissot visited immediately after his arrival (Kisiel M., 2020, p. 179).

Back in France, from Mysticism to Sacred History

In 1883, Tissot organised a retrospective exhibition at the Palais de l'Industrie for his return to the French artistic scene: “Exposition des œuvres de M. J.-J. Tissot, organisée par l’Union centrale des arts décoratifs. Peintures, pastels, eaux-fortes, émaux cloisonnés” (Paris: Palais de l’Industrie, 1883). Presenting nearly two hundred works produced mainly in England (Kisiel M., 2020, p. 184), this was the first French monographic exhibition of works by Tissot. This exhibition included the same works presented at the Dudley Gallery in May 1882 in "An Exhibition of Modern Art by J.-J. Tissot" (London: Dudley Gallery, 1882) (Kisiel M., 2020, p. 272), including the quadrilogy of L’Enfant prodigue dans la vie moderne (1880, Paris, Musée d'Orsay, on deposit at the Musée d'Arts de Nantes, inv. LUX 616 to LUX 619). This series, a great success, became available as engravings (Sciama C., 2005, p. 155-159) and earned the artist a gold medal at the Paris International Exhibition of 1889 (Kisiel M., 2020, p. 274). Tissot, who at the time of its conception was living far from his country with a divorced woman, cultivated a certain affinity with the character and his story (Kisiel M., 2020, p. 184-185). Thus, the series contains several autobiographical details, such as references to his father, Kathleen Newton, and his taste for Japan: it is not insignificant that the second episode, En pays étranger (1880, Paris, museum of Orsay, on deposit at the Musée d'Arts de Nantes, inv. LUX 617), presents the prodigal son in a traditional Japanese inn, watching a geisha show. Between 1883 and 1885, Tissot occasionally exhibited with the Société des Aquarellistes Français and the Société des Pastellistes Français, and frequented, during this period, Louise Riesener (1860-1944), daughter of the painter Léon Louis Antoine Riesener (1808-1878 ), whom he considered marrying (Goncourt E. de, Goncourt J. de, 1989, vol. 2, p. 1192-1193 and vol. 3, p. 382). From February 1885, he consulted the medium William Eglinton (1857-1933) on several occasions to try to get in touch with the spirit of Kathleen Newton – she would have appeared to him on May 20, 1885, which he immortalised in painting in a work entitled L'Apparition (Ysabel Monnier Collection). The same year, Tissot exhibited his series of Quinze tableaux sur la femme à Paris. Among these, La Menteuse (1883-1885, location unknown) presents a young woman between two wall hangings decorated with large Chinese dragons on the threshold of a small boudoir filled with Asian and Oriental objects (Misfeldt W. E., 1982, III -53). While the painter was preparing the last canvas of the Musique sacrée series (location unknown) at the Church of Saint-Sulpice, he had a vision of Christ appearing to a couple of poor people in the ruins of a castle – a vision that he depicts in Voix intérieures (1885, St. Petersburg, Hermitage Museum, inv. ГЭ-4692). This mystical experience marked him. He then almost completely abandoned secular subjects (with the exception of the portraits he continued to produce) and took up sacred history as his theme.

In the context of his new religious fervour, Tissot traveled to Palestine between October 1886 and March 1887, then in 1889 where he made numerous sketches (Kisiel M., 2020, p. 181-183) to prepare the illustrations for La Vie de N.-S. Jésus-Christ: trois cent soixante-cinq compositions d’après les quatre Évangiles avec des notes et des dessins explicatifs, par J. James Tissot (2 vols. Tours: Alfred Mame et fils, 1896). Appointed chevalier de la Légion d’honneur in 1894 (AN, LH/2610/51), he exhibited at the Salon du Champ-de-Mars 270 drawings from the Vie de N.-S. Jesus Christ and completed the 365 illustrations of this first project in 1895 (Kisiel M., 2020, p. 234-237). In 1896, he traveled for the third and last time to Palestine to prepare illustrations of the Old Testament (Kisiel M., 2020, p. 222). In addition to two trips to the United States in 1898, he divided the rest of his life between Paris and the Château de Buillon (Doubs), which he had inherited from his father, where he died on August 8, 1902, leaving six other artists in charge of completing his latest project, La Sainte Bible (Ancien Testament). 400 compositions par J. James Tissot (4 vol. Paris: De Brunoff et Cie, 1904).

Sources for the Study of the Collection

Tissot’s collection can be studied through written sources (posthumous inventories, sales catalogues) as well as photographic and artistic sources (the works of art, painted or engraved, in which Tissot displays his collection).

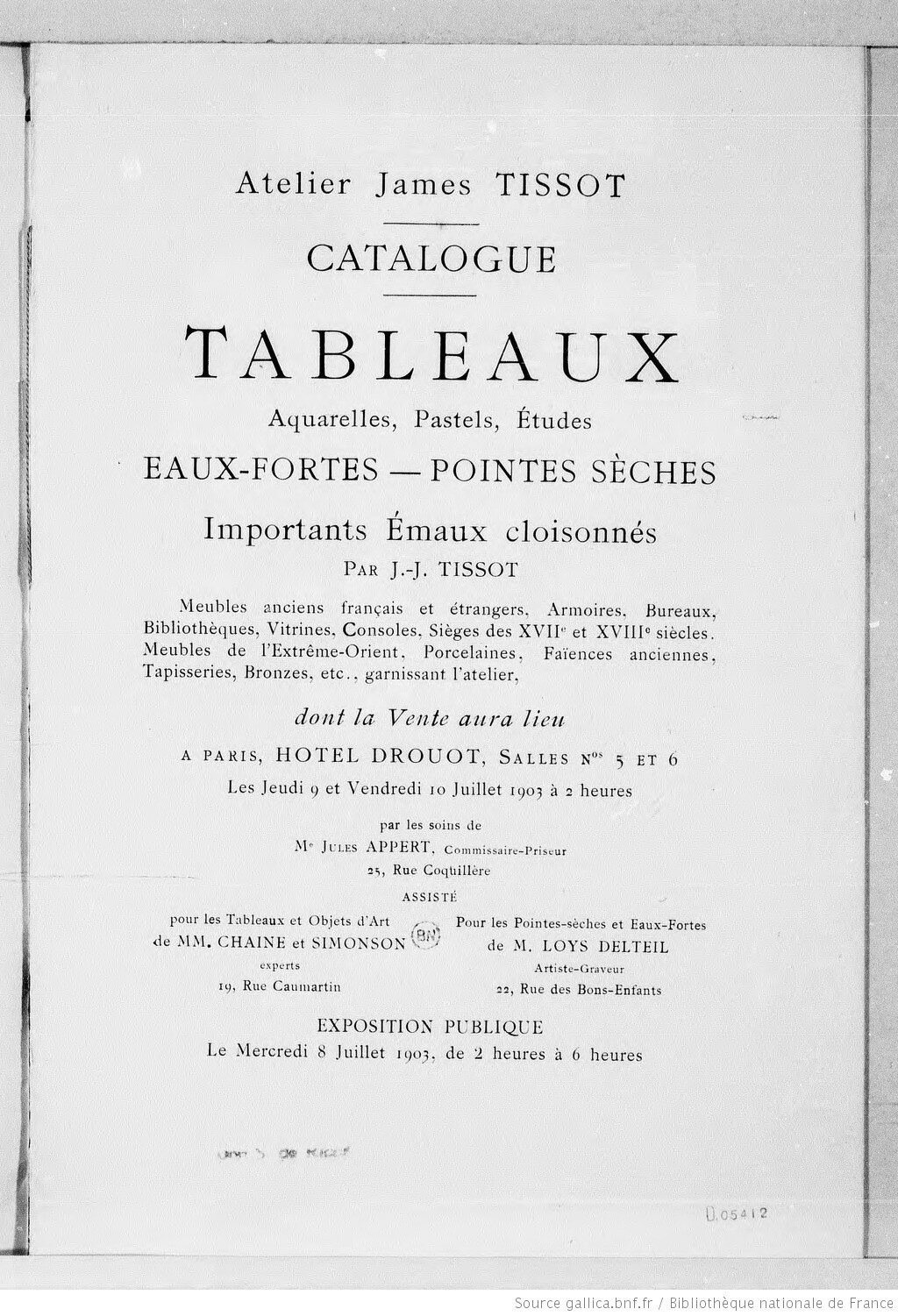

Two posthumous inventories were drawn up following the death of Tissot on August 8, 1902. The first was carried out in 1902 at the Château de Buillon by Maître Dautrevaux, notary (AD 25, 3E44/465); the second was established in 1903 at the artist's Parisian home by Maître Cotelle (AN, MC/ET/LXXXIX/2068). Despite their systematic nature, these inventories do not always provide sufficient details to clearly identify the objects. Some of these goods were then sold: there is a catalogue produced in 1903 for the sale of the Tissot workshop (Appert J., Chaine, Simonson, Delteil, Hôtel Drouot, 1903), presenting the works and objects of art that the artist kept in his Parisian studio located on avenue de l'Impératrice (then avenue du Bois, currently avenue Foch). The Château de Buillon and most of the property that it included were not sold until later, in November 1964, the year of the death of Jeanne Tissot (1876-1964), the artist’s niece who had inherited the château. This last sale, held at the Besançon auction house, took place in three stages, on November 8-9, 14-15, and 21-22, 1964 – the first being devoted solely to the sale of books and the other two to objects and works of art.

When the château and its contents were put up for sale, the photographer Bernard Faille (?-2007) was able to take 31 pictures of the premises (and in particular of the artist's studio) for the newspaper L'Est Républicain. The objects that appear there are in the state in which Tissot left them (AM Besançon, 1964 Ph 22549-22579). There is also a repository of photographs taken during Tissot's lifetime by the artist or by those close to him: the Frédéric Mantion collection, of which six photographs, twelve glass plates, and eight glass negatives have been reproduced in the exhibition catalogue ofJames Tissot, l’ambigu moderne (Kisiel M., 2020). These photographs are precious testimonials that can inform the viewer about the places, arrangement of objects, and certain habits or artistic practices of Tissot.

Tissot regularly staged pieces belonging to him as "main subjects" of his works, as in Rouleau japonais (1872-1873, private coll.), or as decorative accessories scattered in various canvases, such as the Chinese porcelain teapot with a handle in the shape of a dragon found in Holyday (1876, London, Tate/N04413) as well as in Les Rivaux (1878-1879, The Marlene and Spencer Hays Collection). Tissot photographed some of his paintings himself: his four photo albums (Misfeldt W.E., 1982), of which the third is missing, contain 300 pictures. Some of these pictures represent paintings by the artist whose location remains unknown, such as La Menteuse (1883-1885, location unknown).

Bringing together these different sources makes it possible both to cross-reference the objects with each other, but also, in certain cases, to be critical of several designations included in the inventories. Thus, in Buillon's inventory, the "large Japanese lantern in carved and gilded wood with painted silk glasses and curtains" (AD 25, 3E44/465) seems to correspond perfectly to the large lantern presented in Le Bouquet de lilas (1874, private coll.), Les Rivaux or Dans la serre (1874, coll. Diane B. Wilsey, San Francisco). However, according to the representations, this imposing object would rather seem to be a Chinese lantern from the Qing period (1644-1912). Similarly, by comparing the sources, we notice that the combined inventories of Buillon and Paris designate only 27 objects explicitly as Chinese, whereas iconographic sources suggest that Tissot had more: in a small study of 36 works by Tissot and five later photographs, we can count 46 (Lichy H., 2018).

The Tissot Collection: Objects at the Service of an Artistic Practice

James Tissot, "this enthusiast, finding a new 'passion' every 2 or 3 years with which he contracts a new little lease on his life", as Edmond de Goncourt wrote on January 26, 1890 in his Journal (Goncourt E. de, Goncourt J. de, 1989, vol. 3, p. 378), was able to assemble a vast collection of varied objects, as his centres of interest evolved. To his father's collection which he inherited in 1888 (Kisiel M., 2020, p. 274), containing collections of “Japanese and Chinese Antiquities and Shells, II Egyptian Antiquities; III Shells from different parts of the earth, IV Emp birds garlic and birds' nests with blown eggs" (AD 25, 3E44/465), he added objects that he himself acquired over time.

His collection probably began after his arrival in Paris in the 1860s. We know that he made purchases at the establishment of Adolphe Chanton, as indicated by an invoice dated 1867 (Kisiel M., 2020, p. 83). Tissot also visited Madame Desoye's shop regularly, as mentioned above in the letter from Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882) to his mother, dated November 12, 1864 (Rossetti D. G., Rossetti, W. M. , 1895, p. 180), which reports Tissot’s purchase of several costumes to prepare three Japanese paintings.

This anecdote raises questions about the particular function of the objects that Tissot collected as an artist: while some objects were undoubtedly collected out of taste, others were obviously acquired for professional use. It is therefore not insignificant to find a certain number of works from the Tissot collection in his workshops in Paris and Buillon.

In the catalogue for the sale of his Parisian studio, the section devoted to furniture and works of art mentions "Chinese and Japanese dresses in embroidered silk" (Appert J., Chaine, Simonson, Delteil, Hôtel Drouot, 1903). Here it is indeed a question of elements directly serving the artistic practice of Tissot. These clothes or accessories could be used directly by the figures represented in his paintings, as for the kosode of La Japonaise au bain (1864, Dijon, MBA, inv. 2831 and J167). They could also be used to create a fashionable interior – such as the gray "kimono-cloth" used as a tablecloth in Le Chapeau Rubens (towards 1875, location unknown) as well as in Jeunes femmes regardant des objets japonais from 1869 (Cincinnati Art Museum, inv. 1984.217) (Kisiel M., 2020, p. 81). In these two cases, the textile occupies a certain decorative function, but its arrangement in the two pictorial spaces does not allow it to be valued as a "central" object. In Jeunes femmes regardant des objets japonais, it is placed under the imposing model of a Chinese ship which commands the two figures’ full attention. In Le Chapeau Rubens, it covers a piece of furniture placed in front of a window, on which a tall bouquet is placed. If we examine the pictorial space, the textile could almost be considered more as an element of an exotic up-to-date furnishing, rather than as a piece appreciated and collected for its own sake. And yet, Tissot has "chosen" to represent this same fabric at least twice. If we consider the space of the composition of the two canvases, the painter's choices in terms of framing, point of view and color comparisons even inevitably call the viewer's gaze to this fabric. Should it thus be considered the mark of a personal preference or an aesthetic decision?

The objects collected by Tissot can serve as models or subjects, but they also inspired the artist in his work on new artistic techniques. Thus, the Chinese and Japanese cloisonné enamels he owned are linked to his interest in the technique of cloisonné enamel, which he began to practice in London and continued thereafter (Matyjaszkiewicz K., 1985, pp. 95 and Wentworth M., 1980, pp. 127-146). The comparison of a Chinese piece from his collection, called Jardinière Tissot (Paris, musée des Arts décoratifs/26721), dated between the 16th and 18th centuries, with the Jardinière ovale – Lac et mer (1882 or earlier, The Royal Pavilion & Museums, Brighton & Hove), which he created, is enlightening in this regard. Indeed, we recognise many similarities, such as the dimensions, the object’s general shape, its handles and its feet, and the chromatic range of the enamels used. The style of the two works is, however, decidedly different, both in the proposed iconography and in the way of working the metal or applying the enamels: Tissot does not seek to copy this Chinese object but draws inspiration from it freely to create a personal work (Kisiel M., 2020, p. 156-157 and 302-305).

A Collection between Personal Taste and Social Practice

James Tissot is mentioned in 1868 by Zacharie Astruc (1833-1907) (Astruc Z., 1868), then in 1878 by Ernest Chesneau (1833-1890) (Chesneau E., 1878, p. 386) as figuring among admirers of Japanese art from the first. His collection, begun before the Universal Exhibition of 1867 which marked the beginning of the Japanese "wave" among the general public, was noticed by his contemporaries. The critic Jules Champfleury (1821-1889) wrote: "The last originality which must be pointed out is the opening of the Japanese studio of a young painter sufficiently richly endowed by fortune to afford a small hotel particulier in the Champs-Élysées […]. The Japanese studio on the Champs-Élysées, currently frequented by princes and princesses, is “a sign of the times” as Prudhomme would say” (Champfleury J., 1868, quoted in Champfleury J., 1973, p. 143-145). On November 25, 1868, Tissot did indeed receive Princess Mathilde Bonaparte (1820-1904) in his workshop, accompanied by Théophile Gautier (1811-1872) and the brothers Edmond and Jules de Goncourt. She bought La Retraite dans le jardin des Tuileries (“Petits tambours”) (1867, private coll.) from him for the sum of 7,000 francs (Kisiel M., 2020, p. 269). Was Tissot's collection also used as a bait to attract wealthy clients and lovers of Japanese art, or at least to create an attractive showroom for the paintings he offered for sale?

His collection of Asian objects indeed presented some attractions in the eyes of amateurs. It was particularly characterised by its great typological variety. When Tissot died, the collection included textiles (including kimonos and fukusa), accessories (pins, parasols, fans), earthenware, stoneware and porcelain (notably from Imari), tea services, lacquered wood trays, small pieces of furniture, folding screens and screens, five nô masks, model boats, lanterns, a reliquary cupboard, Japanese dolls for Boys’ Day and at least one doll for the Girls’ Day, various trinkets, seven incense burners, an opium burner, bronzes, cloisonné enamels, drawings, and engravings, including eight boxes of Japanese images (AN, MC/ET/LXXXIX/2068 and AD 25, 3E44/465).

These Asian objects were mostly Japanese, but there were also objects that could be identified as Chinese: some examples of textiles (such as those of La Menteuse), at least one model of a boat, the large red lantern in gilded wood mentioned earlier high, furniture items (tables, seats, shelves, pagoda furniture, etc.), cloisonné enamels, a few bronze pieces, dolls dressed in fabric and especially porcelain (cong vases, fang hu, garden pottery, ceramics decorated "blue and white", pieces of tea sets, trinkets, etc.) (Lichy H., 2018).

The painter's collection was certainly built up over many years, but it was able to develop quite quickly from the 1860s, thanks to the family fortune as well as Tissot’s own success and business acumen. His financial situation reached its peak during his stay in London, a period during which the sale of his works allowed him to collect more than 200,000 francs in 1873, which fell to less than 70,000 francs in 1881 (Kisiel M., 2020, p. 294-297). It is likely that most of his Asian objects had already been acquired by this date. Despite interests that varied throughout his life, Tissot nevertheless retained a strong preference for Japan. His purchase of the complete collection of the luxurious journal Le Japon artistique published between 1888 and 1891 by Siegfried Bing (1838-1905) (AD 25, 3E44/465) proves this preference. At that time, Tissot was mainly working on his illustrations of biblical history (in addition to producing a few portraits). It therefore seems that he acquired this publication due to taste, rather than as a search for models or artistic inspiration.

In addition to the particularly well-represented art of the Far East, Tissot was also interested in objects from the Near East. In the inventories drawn up following his death, there are carpets and fabrics, brass, Egyptian statuettes and mosque lamps, two Arab rifles, and a yatagan with an ivory handle. These objects, no doubt acquired during the three trips to Palestine that Tissot undertook in the context of his renewed religious fervour, were not simple travel souvenirs. Some could indeed be linked to the painter's artistic practice, as evidenced by silver gelatine bromide glass negatives from the Frédéric Mantion collection, presenting Études de modèles pour les illustrations de l’Ancien Testament (Kisiel M. , 2020, pp. 226-227).

The collection also included a few works or reproductions of works by particular artists: Tissot had obtained a photograph of Portrait de Madame de Senonnes (1814) by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780-1867), which he greatly appreciated and which he copied in grisaille (Sciama C., 2005, p. 40). Edgar Degas (1834-1917) had given Tissot two of his paintings, Chevaux dans un pré (1871, Washington D.C., National Gallery of Art, inv. 1995.11.1) et Femme regardant avec des jumelles (c. 1877, Dresden, Galerie Neue Meister, inv. Gal.-Nr. 2601), finally sold by Tissot in March 1890 and January 1897 respectively (Buron M., 2019, p. 251), jeopardising their friendship. We also know thatin May 1875 , Tissot had acquired Le Grand Canal à Venise (1875, Vermont, Shelburne Museum/Inc. 1972-69.15) by Édouard Manet (1832-1883), which he sold in March 1890 to Paul Durand-Ruel (1831-1922) (Kisiel M., 2020, p. 271 and 275). Finally, Tissot had also purchased an unidentified canvas by Camille Pissarro (1830-1903), which had been refused by the Royal Academy, in order to help the latter financially during his exile in England (Sciama C., 2005, p. 40).

These various purchases and sales raise questions about the fluctuation of the artist's tastes and motivations. They also make it possible to question the value that Tissot granted the objects in his collection, between personal pleasure, interest, artistic research, social utility, and testimony – or not – to friendship.

Related articles

Collection / collection d'une personne

Personne / personne