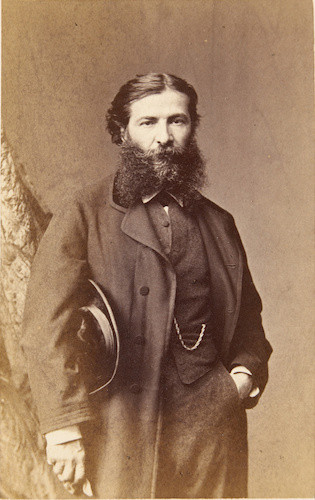

HÉBERT Ernest (EN)

The Years of Training

Ernest Hébert, born on November 3, 1817, was part of the Grenoble bourgeoisie. His father, Auguste Hébert, had taken over the paternal notarial office, adjoining their home in the center of Grenoble. His mother, Amélie Durand, was the daughter of an aristocrat of Provençal origin, a merchant-banker. They had three children: Ernest, the eldest, Valérie, and Oscar, who would later drown in a pond in the garden of La Tronche.

Although the couple separated in 1834, both parents endeavoured to support Ernest as well as possible. His father gave him lessons in Latin, Greek, mnemonics and shorthand at home. Lessons in piano, violin, fencing, horse riding and painting — his passion — completed his education.

At the age of ten, Ernest Hébert entered the studio of the painter Benjamin Rolland (1777-1855), a pupil of Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825). When he left to study law in Paris, the professor arranged with his father that Ernest could simultaneously enrol at the École des Beaux-Arts. In Paris, settled in a small apartment at 30 rue des Saint-Pères, Hébert had access to a workshop located at the back of the courtyard in the rue du Pot-de-Fer and a stipend of 500 francs from his father. He joined the studios of the sculptor David d'Angers (1788-1856), then of Paul Delaroche (1797-1856). Admitted as a lawyer on February 22, 1839, Hébert obtained the Prix de Rome the same year, which opened the doors of the Villa Medici, the French Academy in Rome, which was then directed by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780-1867).

Life at the Villa Medici: Study, Music and Travel

Landing in the port of Civitavecchia, Hébert visited his cousin, the Consul of France, Henri Beyle (1783-1842), better known as Stendhal, who recommended him to his Roman friends. After arriving at the Villa Medici in January 1840, he stayed for the prescribed five years, "leading between music and painting a life of ancient tranquility,” as he wrote to his mother. In the evening, Dominique Papety (1815-1849) taught him watercolours; during the day he traveled the Roman countryside drawing his favourite subjects there. Sometimes he made excursions of a few days: to Naples in the fall of 1842, where he copied the antiquities in the museum; or in Florence in 1843, to study the masterpieces of the Renaissance. At the Abbey of San Salvi, he met Princess Mathilde Bonaparte (1820-1904) and her brother, Prince Napoléon-Jérôme Bonaparte (1822-1891). He would maintain a deep friendship with the princess until the end of his life.

Music held an important place in the life of Ernest Hébert, who had played the violin since a young age. With his friend Charles Gounod (1818-1893), he organised many musical evenings during their stay at the Villa Médici, during the more intimate of which Ingres might be heard playing the violin in a Beethoven quartet.

After being immobilized by a broken leg in Florence, Ernest Hébert obtained a two-year extension of his stay from Jean-Victor Schnetz (1787-1870), successor to Ingres as director of the Villa Medici. This initial stay in the peninsula would profoundly mark Ernest Hébert, to the point of him making it his adopted land. He ended up spending thirty years of his life there and persistently postponed the date of his return to France.

Parisian Life: Hébert, Society Portraitist

After another fall forced him to stay in Marseille for a year, Ernest Hébert returned to Paris in May 1848 and settled in his father's mansion at 11 rue de Navarin, in the ‘New Athens’ district (9th arrondissement). He was absorbed by painting La Mal’aria, composed in Italy; it offered him his first great success at the Salon of 1850 (Paris, Musée d'Orsay, inv. 5299). Tired of life in Paris, he returned to Italy in September 1853 with two landscape painter friends, Édouard-Auguste Imer (1820-1881) and Eugène Castelnau (1827-1894), for a four-month trip to the countryside around Rome and the Abruzzo. Two of his best works date from this trip, Les Filles d’Alvito (Paris, Musée Hébert, inv. RF1978-54) and Les Cervarolles (Paris Musée d’Orsay, inv. MI 225). Les Filles d’Alvito, as well as Crescenza à la prison de San Germano (Paris, Musée Hébert, n.inv. RF1978-58), were awarded first-class medals (historical genre) at the Universal Exhibition of 1855.

There followed a period of eight years in Paris, during which he joined the circle of fashionable artists. He was familiar with Princess Mathilde, cousin of Napoleon III (1808-1873), and frequented her salons (at her mansions in rue de Courcelles in Paris and in Saint-Gratien, near Enghien), which were high places of cultural life in the Second Empire. He rubbed shoulders with artists - Paul Baudry (1828-1886), Victor Giraud (1840-1871), Alexandre Cabanel (1823-1889), Charles Jalabert (1818-1901) — and writers — Hippolyte Taine (1828-1893), Ernest Renan (1823-1892), Gustave Flaubert (1821-1880), the Edmond brothers (1822-1896) and Jules (1830-1870) de Goncourt, Charles-Augustin Sainte-Beuve (1804-1869), Alexandre Dumas fils (1824-1895), and so on. Official orders flowed in, notably from the imperial family. The portrait, the favourite genre of the bourgeoisie and the aristocracy, was perfectly mastered by Ernest Hébert, who was able to reveal the social status of the model with elegance and subtlety. The numerous commissions that he executed gave him great material freedom: “It is for me that I work when I make paintings; when I do portraits, it's different," he wrote to his mother. As a socialite, Ernest Hébert almost exclusively painted women of Parisian high society. The painter placed them in closed and hushed settings, in front of drapes saturated with colour, or in the open air. He matched the background to the figure, by modulating the colours to the extreme, excluding black and white, and thus gave the paintings a sweet nostalgia. As early as 1890, Ernest Hébert demonstrated technical audacity by incorporating cheap pearls or brilliants into his portraits. During the year 1900, he produced twenty-six portraits, with a predilection for the princely families of Europe, especially the Bonapartes. He also favoured the artistic milieu and that of the Haute Banque. His portraits, which represent boththe physical and the spiritual, highlight the characters and their particularities.

Italy, Adopted Land of Inspiration and Creation

Thanks to Princess Mathilde and Count Emilien de Nieuwerkerke (1811-1892), the Superintendent of Fine Arts, Ernest Hébert was appointed director of the Villa Medici in 1867, and he returned to Italy with great joy. During this first directorship, Ernest Hébert invested in an intense social life, by organising social events and group outings to his favourite sites and concerts every Sunday evening. In 1872, he painted La Vierge de la Délivrance (Paris, Musée d'Orsay, inv. RF 1978 211), which was presented at the Universal Exhibition of 1889 and installed in the church of La Tronche. As an appointed member of the Institute, he returned to Paris in 1874, where he would later assume the position of professor at the Beaux-Arts. Ernest Hébert moved to 55 boulevard Rochechouart. There, he met Gabrielle d'Uckermann (1853-1934), a young German aristocrat who was passionate about art and an admirer of his work. They married in the church of La Tronche in November 1880. Together they had Mathilde-Ernestine, an only child who died at birth on November 25, 1882. A commission by the director of Fine Arts for a mosaic decoration project for the apse of the Pantheon gave him the opportunity to return to Italy, to once again study the old masters. The mosaic was inaugurated in 1884.

In June 1885, Ernest Hébert, then 67 years old, was tapped for a second directorship of the Académie de France in Rome. He found, however, that Rome had changed; he described its destructive modernisation in Roma Sdegnata (Hébert E., 1896). After being replaced at the Villa Medici by Ernest Guillaume (1822-1905) in 1891, Ernest Hébert remained in Italy for another five years. In 1894, he had the opportunity to receive Émile Zola (1848-1902), who had come to take notes for Rome (Zola E., 1896), his novel in progress. The Héberts showed him the Sistine Chapel and the Raphaël rooms in the Vatican. In Rome, Zola bought an antique mask, which the painter bought after the writer’s death in 1902 and installed in the garden of La Tronche. During this last stay in Italy, Ernest Hébert painted, among others, Bibiana in 1889 (Grenoble, Art Museum, inv. MG 1616), La Vierge au chasseur in 1892 (MO, inv. RF 1978 218), and the Vierge Addolorata, also in 1892.

In October 1896, Ernest Hébert returned to Paris at an advanced age and continued to paint and lead an intense social life. He went out almost every evening to concerts or to the theatre and received literary celebrities, such as Anatole France (1844-1924), Marcel Proust (1871-1922), and Edmond Rostand (1868-1918). In December 1896, he was made a grand officier de la Légion d’honneur. In 1900, on the occasion of the Universal Exhibition, he received the Grand-croix. On August 2, 1908, Ernest Hébert returned to Isère to see his childhood home. While suffering from pneumonia, he died on November 4, 1908, aged 91. He is buried in the vault built in the garden of his house in La Tronche.

The Collection

In 1867, the first pavilion of the Empire of the Rising Sun, presented at the Universal Exhibition, achieved considerable success and launched the fashion for Japanese objects. Many shops of "chinoiseries-japoneries" opened and offered all kinds of imported exotic items, often made especially for Europeans. Among the forerunners of this taste, the Goncourt brothers, Jules and Edmond, were absolutely fascinated by these objects, which they collected in an oriental cabinet that overflowed onto the steps of the staircase of their house in Auteuil. Jules de Goncourt wrote a letter in 1867 to Philippe Burty (1830-1890), inventor of the concept of "Japonisme", which he concluded with “Japonaiserie for ever.” Edmond de Goncourt was one of the first, in La Maison d'un artiste (Goncourt (de) E., 1881) then in the Journal (Goncourt (de) E. and J., t.7, December 14, 1894, 1894) to draw attention to these ceramics, lacquer panels, chests, fans, and prints. The taste for trinkets, rare objects, and even junk developed gradually and “descended to the bourgeois,” as the two brothers had already noted in their diary of October 29, 1868 (Goncourt (de) E. and J., t.3, 1888). Hayashi Tadamasa (1854-1906), who came as an interpreter for the Universal Exhibition of 1878, established himself in 1883 as an art dealer. As general curator of the Japanese committee for the 1900 World's Fair, he would greatly contribute to the spread of Japonisme. Having become the darling of le Tout-Paris, he was connected to the Goncourt brothers, in particular Edmond, whom he helped with his writings on Japanese artists (Outamaro, le peintre des maisons vertes, 1891, and Hokusaï, 1896). Through them, Hayashi Tadamasa became friends with Princess Mathilde and the painter Ernest Hébert. The latter, as well as his wife, was solicited in a letter from the princess dated Friday, November 9, 1900: "Will you come dine next Monday and tell Hayashi to come too? I lost his address. Best wishes. Mathilde” (Paris MNEH, 1978-7-452). It was probably under the influence of the Japanese that Hébert made the acquisition — or were they gifts? — of the Japanese objects in the museum's collections: kimonos, ceramics, fans, harmonicas, furniture, etc., alongside Chinese objects. This veritable bric-a-brac confirms the enthusiasm for Far Eastern exoticism displayed in salons and artists' studios in Paris (Claude Monet, 1840-1926) as well as in the provinces (General Léon de Beylié, 1849-1910), at the end of the 19th century.

Related articles

Personne / personne

Collection / collection d'une personne