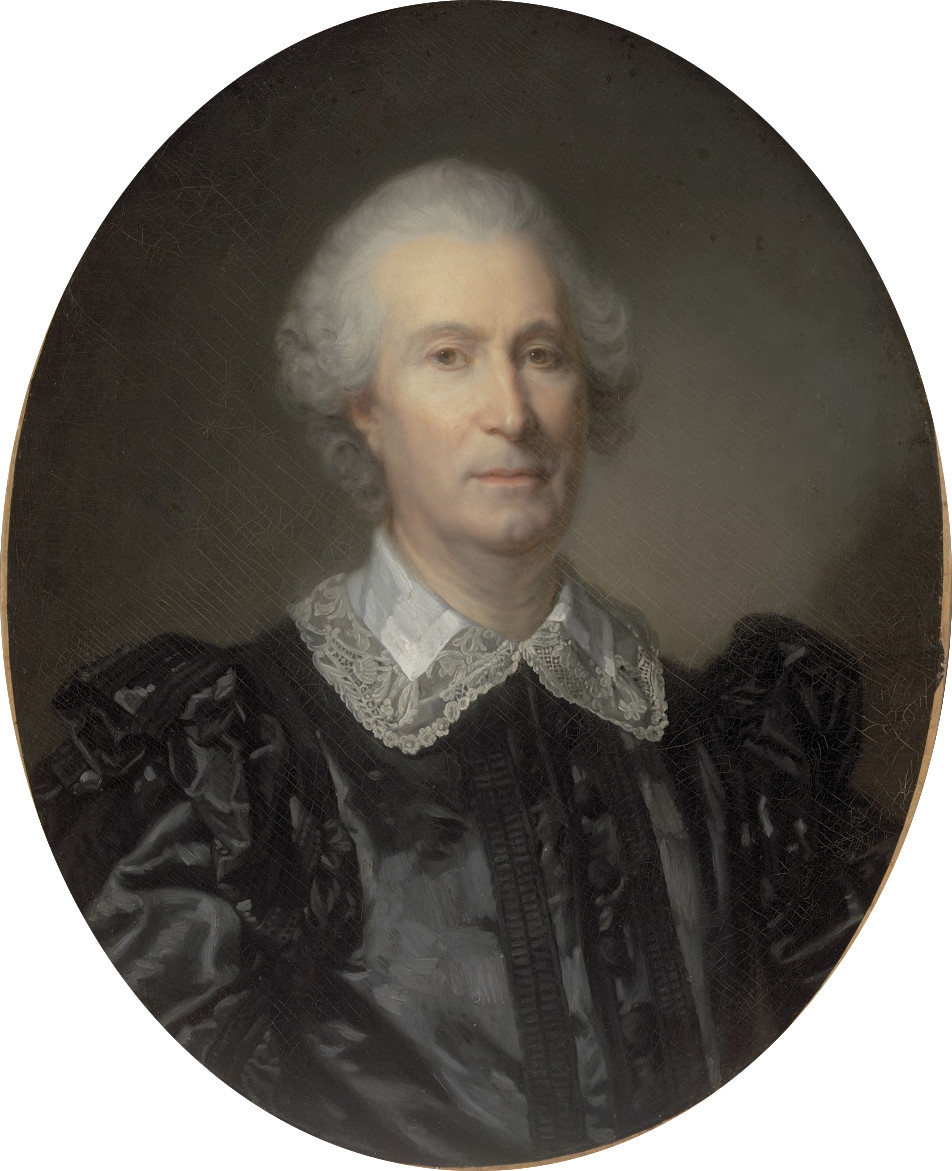

RANDON de BOISSET Paul Louis (EN)

Financier and Connoisseur

Paul Louis Randon de Boisset was born in Reims on October 25, 1709 to Paul Louis Randon de la Randonnière, Receiver of Finances in Montdidier, and Françoise Juillet (Mazel G., 1987, p. 47). His father came from a wealthy family of wool merchants from Anduze. After receiving a brilliant education, Randon de Boisset became a lawyer in the Parliament of Paris in 1736 and then embarked on a career as a financier (Ris de C., 1877, p. 361-362). Both his own preference and a push from his family led him to take an interest in business and become farmer-general from 1757 to 1758. However, he abandoned this function for a position as Receiver General of Finances in Lyon. According to the merchant Lebrun, he would have preferred this function "which, less coercive than the first, gave him more time to indulge his taste for literature and the fine arts" (Mazel G., 1987, p. 4 n .1; p.41). Randon de Boisset was an ardent collector. His first interest was books, and his beginnings as a bibliophile date back to the 1740s (Beurdeley M., 1988, p. 48-55). His sizeable collection was then also known for its quality and the rarity of certain copies (Rémy P., 1777, p. 5). Painting was another interest. Randon de Boisset also became friends with several artists, such as François Boucher or Jean-Baptiste Greuze, and made two trips to Italy, in 1752 during which he met Joseph Vernet, and again in 1762 (Rémy P., 1777, p. 2-4). His recent taste for painting became a real passion, and he devoted considerable sums to his collection. He visited Holland and Flanders with Boucher in 1766 and discovered his boundless enthusiasm for Dutch painting. From then on, the three schools (the North, the French, and the Italian) would be present in his cabinet, which was enriched thanks to the advice of Pierre Rémy, a marchand-mercier to whom he was introduced by Boucher (Beurdeley M., 1988, p. 6). This remarkable set was dispersed when the collection was sold in 1777 (Rémy P., 1777). However, Randon de Boisset was not only interested in books and paintings; he also collected decorative arts. In 1772, he left Place Vendôme for Rue Neuve des Capucines where he settled in a large hotel particulierthat he had had built by the architect Gabriel. This new residence housed his library and his painting cabinet, and also admirably presented furniture and works of art (Rémy P., 1777, p. 5).

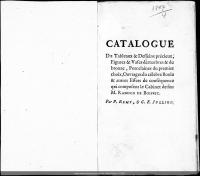

The study of the posthumous sales catalogue provides a glimpse into the richness of this collection. The first part of the catalogue, written by Pierre Rémy, concerns the objects of fine art. The rest of the catalogue deals with the decorative arts and curiosities, "the surplus of the curious and precious effects of this Cabinet" (Julliot C.-F., 1777). Despite its fame, Randon de Boisset's collection was not publicly very visible at the time. Unlike other contemporary collectors, Randon de Boisset did not open his cabinet to the public (Rémy P., 1777). In fact, his collection was discovered by amateurs and other curious people during the public sale, as Pierre Rémy testified shortly thereafter in the catalogue of the sale of the Prince of Conti: "M. de Boisset, so gentle, so honest, but not so communicative, regarded, so to speak, his Cabinet as a sanctuary to which not everyone could gain admission. To achieve this, it was necessary to be connected with M. de Boisset, to pray to him, to solicit him: thus his Cabinet, though famous, was nonetheless known to few people. To remedy this inconvenience, his heirs opened it. With what ardour and throngs the Public came! People came out filled with admiration, and everywhere people spread their praises over the masterpieces contained in this cabinet” (Rémy P., 1777). Randon de Boisset died in the midst of these splendours in September 1776. He was buried on September 30, 1776 in the cemetery of the parish of Saint-Roch. As a bachelor, he had designated his two nephews as universal legatees, Jean-Louis Millon d'Ainval, Receiver General of Finances of Lyon, and Augustin Million d'Ailly, Receiver of Domains and Woods of Paris, both sons of one of his three sisters (AN, M.C., LXXXIV/546, October 18, 1776, posthumous inventory of Paul-Louis Randon de Boisset). They were the ones who decided to put the collection on sale, which took place at his home in the hotel particulier on rue Neuve des Capucines. Paul Louis Randon de Boisset was primarily known for being the owner of one of the finest collections in the kingdom, whose dispersion was a significant episode in February, March and April 1777. The outcomes of the sale reached very high prices. As an example of the enthusiasm aroused by the sale, Michel Beurdeley (1988, note 9 p. 6) cites a passage from a letter from the Academician Watelet to one of his friends: "...you would have seen the spectacle of the sales of M. de Boisset where all the objects are sold at inconceivable prices..."

There are few documents on this collector that would allow us to better understand his career and his personality, but the sales catalogue and the posthumous inventory provide valuable information about the history of taste in the second half of the 18th century, particularly in the area of Asian art collections.

A Valuable Collection

The study of Randon de Boisset's collection, beyond its intrinsic interest, allows us to understand the extent of the taste for Asian arts in the second half of the 18th century. Indeed, the manner in which the pieces are presented in the sales catalogues, estimated according to their form, origin, and passage through the hands of renowned collections, shows that they were no longer considered only as objects of curiosity but that a real Far Eastern "culture" was emerging, among amateurs and dealers alike: more importance was now attached to the object’s origins, age, or technique of manufacture. For the study of the section of the catalogue concerning lacquers and porcelains, inspiration can be taken from the essay by Krzysztof Pomian entitled "Marchands, connaisseurs et curieux à Paris au XVIIIe siècle" (Pomian K., 1987). In this article, the author shows the evolution of sales catalogues during the 18th century: in the notices of the paintings, we go from a simple description with a more or less certain attribution, to a highlighting of the name of the artist with a more precise description, which allows the merchant who offers these justified attributions to access the title of "connoisseur". This approach can be partially transposed to lacquers and porcelains, markers of Asian taste in the collections of this era. Thus, with regard to lacquers, one can note in the catalogues, including that of Randon de Boisset, a desire to highlight the differences in provenance and quality of the objects.

From the 17th century on, imports of products from the Far East became more frequent, and European shipowners and merchants began to distinguish lacquerware from Japan from that of China, preferring the former for its markedly superior quality; a distinction was also made between old and new lacquer. However, the knowledge of lacquers by French experts was refined even more clearly from the second quarter of the 18th century: the distinction between old and new lacquer then corresponded to a real difference in dating, i.e. "old lacquer" for the lacquers of the previous century, of better quality, and "new lacquer" for contemporary lacquers. This distinction was often taken up by experts in the second half of the century and resulted in significant differences of price (Wolvesperges T., 2000, p. 12).

In the second half of the 18th century, Randon de Boisset was in possession of one of the most important collections of lacquerware, after that of the Marquise de Pompadour. His collection was mainly made up of decorative objects, with only three pieces of lacquer furniture: two dressers by Levasseur with drawers in Japanese lacquer and an armoire. These pieces of furniture were sold at high prices when the collection was dispersed (respectively 3,500 pounds (lot 772 of the catalog) and 1,410 pounds (lot 771)) and thus count among the most luxurious goods. The rest of Randon de Boisset's lacquer collection consists, according to the catalogue compiled by Julliot, of around thirty lots comprising cassolettes, bottles, barrels, trays, tubs, animal and fruit figures, vases and boxes. The descriptions emphasise origin and quality, with Japanese lacquers being the most popular, as well as provenance, with some pieces coming from the cabinets of famous amateurs. Thus, the "Van Diemen" box (according to the inscription on the lid; today conserved at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London) comes, with four other lots, from the collection of the Marquise de Pompadour. The latter was at the time considered to be a connoisseur of lacquerware and art, and it is likely that her previous ownership of this box contributed to the high price (6,900 pounds) obtained at the Randon de Boisset sale.

Porcelain from China and Japan also constitutes an important part of this amateur's collection of Asian arts, both in number and in quality.

The catalogue compiled by Julliot tells us that the collection had no less than 167 lots. About thirty types of objects can be distinguished, both utilitarian and decorative, grouped into four categories: porcelain used in the composition of table services (cups, saucers, teapots, sugar bowls, goblets, plates, water jugs, bottles, etc.), other utilitarian porcelains (tea, sugar and tobacco tins, tobacco canes, vases, flower picks, toilet chests, etc.), decorative porcelains (magots, pagodas, animals, fruits, urns, cassolettes, mortars, etc.), and finally furnishings (torches, chandeliers, magots in the shape of writing desks or clocks, etc.).

Many pieces included a gilt bronze or silver mount (Julliot C.-F., 1777, p. 9). Indeed, the marchand-merciers did not hesitate to pierce or cut pieces of porcelain to add mounts made in Paris. Pedestals made of precious materials were also added, mounts and pedestals then forming composite works of art whose marble and bronze competed in value with that of the original ceramics.

In the catalogue, Julliot chooses to classify the porcelains by type: we find first of all the "coloured first quality porcelains", the most important category, by number as well as by quality; it includes eighty-seven lots (lots 499 to 586). Then come the "Old Japanese porcelains", which include twelve lots (lots 587 to 599), the "Old Japanese celadon porcelains" also composed of twelve lots (lots 600 to 612), two lots of "coloured porcelain lapis from ancient China" (lots 613, 614), three lots of "ancient white porcelain from Japan" (lots 615 to 618), then twenty-three lots of "celestial blue porcelain from ancient China" (lots 619 to 642). Next in the catalogue are the "violet porcelains from ancient China" (lots 643 to 645), the "coloured porcelains from China" (lots 646 to 653), the pieces grouped under the heading "ancient land of the Indies" (lots 654 to 661), the "old blue and white porcelain from Japan" (lots 662 to 664) and, finally, the "old blue and white porcelain from China" (lots 665 to 674). At the end of the catalogue come the porcelains of Sèvres and Saxony, then the service items.

Japanese porcelain, or porcelain identified as such, figures prominently in the collection of Randon de Boisset. In fact, from 1720 onwards, these were the subject of a real craze, when supply shortages due to the fall of the Ming at the end of the 17th century diverted customers from Chinese porcelain. The latter is nonetheless very present in the cabinet of Randon de Boisset, including in particular "blue and white of China" exhibited in a living room on the first floor of his sumptuous residence. Some porcelains, like lacquers, had passed through the hands of famous connoisseurs. Julliot quotes in his notes the passage of the pieces in the cabinets, which were then figures of reference. Thus, we learn that certain pieces of "first quality coloured porcelain" had passed through the cabinets of M. de Fontpertuis (sale in 1747) and the Duc d’Ancezune (lot 520 for example), or even M. de Jullienne ( lot 514) (Julliot C.-F., 1777, p. 9). There is also mention in the catalogue of pieces from the cabinets of M. le baron de Thiers, M. le Comte de Fontenay (for celadons), M. Boucher, M. le duc de Tallard (notably for "porcelains of 'ancient blue and white China'), and finally from Madame la Marquise de Pompadour (for example, a piece depicting a cat, in 'celestial blue porcelain from old China').

The sale of the porcelains resulted in sales receipts that were quite exceptional for the time (almost 88,000 pounds). Julliot was probably the most important buyer of lacquers as well as of porcelains. Not only did he mediate for many individuals, but he also bought a good deal for himself. Like a number of merchants, he apparently had difficulty making his payments. After the death of his wife, he proceeded to sell his entire estate in October 1777 and made a compensation, through the intermediary of the auctioneer Chariot, between the proceeds of this sale and the 11,219 livres 17 sols still owed from purchases at the sale of Randon de Boisset (Beurdeley M., 1988, p. 6). While the prices were relatively high during the Julliot sale, they only rarely exceeded those reached during the sale of Randon de Boisset. Thus, lot 102 of the Julliot catalogue, two porcelain bottles with marble and gilt bronze mounts, was sold for only 500 pounds, whereas at the Randon de Boisset sale, 670 pounds was attained for the same piece.

Related articles

Collection / collection d'une personne

Personne / personne