SARTEL Octave du (EN)

Biographical Article

Octave du Sartel became known for his work on Chinese porcelain by publishing the first monograph in French language on the subject in 1881. He had a significant collection of art works, which would be dispersed during two sales in the second half of the 19th century.

Octave Charles Waldemar Frémin du Sartel was born on January 6, 1828 in Douai in northern France (LH, 1033 35 p.5). He was the third child of Jean-Philippe Frémin du Sartel (1792-1864) and Eugénie Joséphine Adelaïde de Carondelet (1791-1855); his brothers and sisters were Adèle Cornélie (1815-1902), Jean Philippe Eugène Léon (1817-1881), and Marie-Charlotte (1829-1900). His grandfather, Jean-Philippe Frémin du Sartel, was lord of Quesnines, Baratte, Sart-le-Sartel, and alderman of Cambrai. His father was bodyguard to King Louis XVIII and Knight of the Legion of Honor (AN, LH/1033/34). His mother, daughter of Messire François, Viscount of Carondelet (1759-1807) and Angélique de Turpin-Crissé (1765-1835), came from the prestigious Carondelet family, originally from Bresse and settled mainly in Burgundy, where, during the Renaissance, several members of the family distinguished themselves as prelates and patrons of the arts and letters. She was also the direct descendant of Marshal Ulrich Frédérique Woldemar de Lowendal (1700-1755), Knight of the Order of the Holy Spirit. This refined and artistic background likely inspired Octave du Sartel with a vocation for collecting and a full commitment to the artistic circles of his time.

His career in the Navy seemed clearly charted. At only eleven years old, he entered the naval school, and three years later, in 1841, he became a midshipman in the port of Brest. According to his Legion of Honour file, he participated in the capture of the Marquesas Islands and the annexation of Tahiti aboard the Triomphante under the command of Abel Aubert Dupetit-Thouars (1793-1864). He was appointed ensign starting November 1, 1845. After only two years of service, however, he resigned on January 20, 1847, a few days after his marriage.

On January 12, 1847, he married Mathilde Marie van Alstein (1823-1883) in Brussels who was originally from Ghent. From their union three children were born: Georges Jean Philippe Waldemar Frémin du Sartel (1848-1904), Marie Mathilde Antoinette Frémin du Sartel (1849-1919) and Gaston Léon Jean Frémin du Sartel (died August 2, 1885). The family resided at 18 rue Lafayette.

There followed a long period between the beginning of the 1850s and the end of the 1870s during which little information is available regarding his activities. On March 15, 1862, he joined Adolphe Brudenne, a manufacturer of stearin (a material used in the manufacture of candles), along with the Counts Joseph Erard and Ernest de la Vaulx to form a company dedicated to the manufacture of stearin and the sale of its products, called "Société de stéarinerie Brudenne" (Madre, 1862, np). It was a family venture since Count Érard de La Vaulx was the husband of Octave du Sartel’s older sister. The company took the name of P.-P. Marin et Compagnie when Philippe Marin bought the shares of Adolphe Brudenne. The company was under this name when it was dissolved in 1866 and Octave du Sartel was named its liquidator (Hèvre, 1866, n.p.). Octave du Sartel undoubtedly pursued other commercial activities of this sort, although to date no specifics have been identified. In his will, he bequeathed a few objects to his "assistant", a certain Alphonse Poisat, annuitant, residing in Paris at 1 rue Viollet-le-Duc, and who served as a tutor to one one of Octave du Sartel’s minor daughters, Elena Mathilde Frémin du Sartel, during the process of succession (AN, MC/ET/VIII/1944).

The Universal Exhibition of 1878 marked the beginning of his full investment in the artistic circles of his time. For this occasion, he exhibited some works from his collection in the retrospective section at the Trocadéro that presented works from China and Japan.

In 1883, he joined the Improvement Commission of the National Manufacture of Sèvres (SMMN, U33 bundle 3), which had been created by a decree of July 26, 1872, to foster the improvement of its products. As a member of this assembly, he submitted a report to the Minister of Public Instruction and Fine Arts in 1884 on the various technical orientations recommended for the factory. In this short text, the author reports on the technological progress made by the manufacture since the beginning of the 19th century and then reaffirms Sèvres's intention to unravel the mysteries of certain Chinese techniques, such as translucent enamels on porcelain, ox blood stain, and celadon "glazes" (Du Sartel, 1884, p. 7-8). At his home he kept test vases from the Sèvres factory (AN, MC/ET/VIII/1944), as well as some Sèvres pieces bearing his coat of arms.

In 1884, he was part of the organising committee of the retrospective exhibition of the Union centrale des arts décoratifs and lent some of his works for the occasion. In 1889, he directed the ceramics section of the ancient exhibition within the Universal Exhibition (Eudel, 1889, n.p.).

From the end of the 1870s, he received numerous decorations: Officer of the Academy on October 24, 1878, Knight of the Order of Charles III of Spain on May 16, 1882, and Knight of the Order of Franz Joseph of Austria-Hungary on April 13, 1885 (AN, LH 1033 35).

Ailing, Octave du Sartel seems to have taken his own life at his home on April 10, 1894 (Anonymous, 1894, n.p.). He is buried in the Montmartre cemetery and a funerary plaque in his name is installed in the chapel of the Château de Potelles, the family home where his wife was already buried (Vienne A., 2020).

The Collection

Octave du Sartel's collection is best known for its Chinese porcelain. He undertook highly advanced studies of Chinese porcelain and presented on this topic in his book entitled La Porcelaine de Chine. Two sales make it possible to reconstitute his entire collection, one carried out during his lifetime in 1882 (Lugt 41877), the other organised posthumously as part of his estate (Lugt 52697).

Publication on Chinese Porcelain

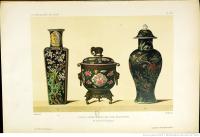

Published in 1881, du Sartel’s book La Porcelaine de Chine. Origine. Fabrication, décors et marques. La porcelaine Chine en Europe. Classement chronologique. Imitations, contrefaçons is the first monograph in French entirely dedicated to this subject. The work was produced in a prestigious edition: the text is accompanied by xylographed illustrations, and shimmering chromolithographic plates alternating with etchings and heliogravures of nearly 150 objects are collected at the end of the work. The majority of the illustrated works come from the collection of Octave du Sartel.

Octave du Sartel presents his work as the result of "a few notes" accumulated over the years until reaching the stage of a coherent book. All this work had been encouraged by "accomplices" whose names he does not reveal (Du Sartel, 1882, np). In his précis of the book, the art critic Philippe Burty (1830-1890) gives some clarifications on the work’s genesis: Adrien de Longpérier would have suggested to the author to carry out an in-depth work on Chinese porcelain following the Universal Exhibition of 1878, during which the Du Sartel collection was first presented. Originally, this work was meant to be included in the general catalogue of the Exhibition, but this project never saw the light of day. Longpérier apparently drew Octave du Sartel's attention to the fact that "the classification of Chinese porcelain was still purely empirical" (Burty P., 1882, n.p.) and emphasised the need to update knowledge about it. The fact is that since the publication of the pioneering works of Albert Jacquemart (1808-1875) of the early 1860s, no new writers in France had revived the field of Chinese ceramics. At the same time, the classification developed by Jacquemart was increasingly criticised to the point of falling into disuse at the dawn of the 1880s (Garnier, 1882, p. 403).

Octave du Sartel thus tackles several subjects which were debated in the 19th century, the first, and not the least, being the origins of Chinese porcelain, which he sought to reduce to "less legendary proportions" (Du Sartel O., 1881, p. 35). For him, the first Chinese porcelains were made at the end of the 9th century, thus opposing the sinologist Stanislas Julien (1799-1873) who placed them at the beginning of our era (Du Sartel O., 1881, p. 5-6) . He attacks Stanislas Julien on his own ground, that of sinology: for Octave du Sartel, the appearance of the term yao 窯 (kiln) replacing the term tao 陶 (ceramic, terracotta) under the Tang (618-907) is not the sign of a linguistic evolution but of the arrival of new hard and white paste products: porcelain (Du Sartel O., 1881, p.4). He thinks that the "hidden colour porcelains" 秘色窯 (miseyao) referred to several times in anecdotes dating from the ninth century refer to "a kind of porcelain highly esteemed at the time of its appearance" (p.7). Finally, the fact that the terms yao and ci (磁 "porcelaine") have no ancient spelling allows him to demonstrate that porcelain did not exist before the standardisation of the use of characters in kaishu (楷書) form under the Song 宋代 (Du Sartel O., 1881, p.6).

From the perspective of expertise, Octave du Sartel restores a large number of attribution errors conveyed by the works of Albert Jacquemart. The first is to reestablish the authorship of the porcelains that we know today as kakiemon to Japan. These works, characterised by the use of a milky white glaze and a predominantly red, blue, green and yellow overglaze enamel decoration, had been attributed to Korea and placed in the category of "archaic families" proposed by Albert Jacquemart (d'Abrigeon P., 2020, p. 88). Based on the works and documentation brought by the Japanese Imperial Commission on the occasion of the universal exhibitions, Octave du Sartel affirmed that the so-called eggshell porcelains, decorated with enamels from the famille rose palette, could in no way be attributed to Japan, which did not bring such objects to any of these events (Du Sartel P., 1881, p. 12-13). He rightly argues that these works are indeed Chinese and are, for the most part, attributable to the Yongzheng period (1723-1735).

What clearly distinguishes the work of Octave du Sartel from that of his predecessors is his attachment to chronology. The "main purpose" of the work was to arrive at the classification "in order of relative antiquity" of the porcelains that make up its collection (Du Sartel O., 1881, p. 111). From the first chapters of the book, he establishes a clear distinction between "modern" and "ancient" production. Considered inferior, modern works, that is to say, produced in his time and which nevertheless continued to elicit an "unreflected infatuation" (Du Sartel O., 1881, p. 1-2), "shock the artistic sense of anyone who has fallen in love with the genius of the Orientals.” Thus, his book is essentially interested, error in attribution aside, in works prior to the end of the reign of Qianlong (1796) (Du Sartel O., 1881, p. 2). Having established this prerequisite, he proposes a classification of ancient Chinese porcelain according to three methods. The first consists of drawing up a chronology of undated manufacturing marks, i.e. all those representing a figurative or abstract motif and not a reign mark (nianhao 年號). To do this, he lists all the marks and inscriptions of some 632 pieces in his collection and groups around works bearing inscriptions dated by stylistic correspondence, others bearing simple marks without chronological indication. The result is a numbered and dated table of these marks (p.100-110). He thus classifies several marks representing two fish linked together by the mouth (marks no. 88 and 94, p.106-107) as being dated 1662, in other words the beginning of the reign of Emperor Kangxi (1662-1722). His second method consists of relying on the inventories of old European collections, starting from the postulate that the works acquired over the past centuries were more or less of manufacture contemporary with the date of their importation (p.117). He thus deduces that the polychrome decorations on glaze did not appear until 1650 (p.121). Prior to this, porcelain production was essentially made of blue and white, as illustrated by 17th-century Dutch painting. Finally, Octave du Sartel completes his classification by meticulously reading the only treatise on Chinese porcelain that was translated into a Western language at his time: the Jingdezhen taolu (景德鎮陶錄 Records of Jingdezhen Ceramics) - partially translated by Stanislas Julien and published in 1856 under the title Histoire et Fabrication de la porcelaine chinoise – which he tried to apply to the works in his collection. This method would allow him to precisely situate a Ding-type 定 piece from his collection at the Song period (D’Abrigeon P., 2018, p. 117).

Another originality of the book is to offer one of the very first "European histories of Chinese ceramics" (p. 113). Octave du Sartel retraces the history of Chinese porcelain in Europe, from the first mention of objects in the fourteenth century to the arrivals of the Summer Palace (Yuanmingyuan 圓明園), passing through the evocation of the great collections of the eighteenth century. The author positions himself as the custodian of a "long tradition" of illustrious collectors and defends himself against any detractor who would like to see in his windows "the product of a bizarre and disordered taste that arose in a jaded century which, weary of truly beautiful things, suddenly falls in love with infinitely small matters of art and seeks new sensations in its disdained recesses” (p. 118). To support his argument, he describes a whole genealogy of illustrious men who collected Chinese porcelain: Sully, the Duc d’Orléans, the Grand Dauphin, Angran, Viscount of Fonspertuis, M. de Julienne, Randon de Boisset, etc., detailing the content of their sales catalogues and sometimes illustrating the descriptions with works from his own or from other contemporary collections (p.126-139).

From the perspective of terminology, Octave du Sartel preserves certain denominations that have come into common use, such as those of the “famille verte" or “famille rose”, but frees himself from the rest of the nomenclature developed by Albert Jacquemart and Édmond Le Blant, which was appreciated by his contemporaries: "The author - rare thing! - managed to avoid the ridiculous pedantry of certain writers who dealt with ceramics, with words that never end, such as chrysanthemo-poeonian - the sesquipedalian verba of Horace. He simply wrote his book in good, solid language that everyone could understand. We cannot congratulate him too much” (Bric-à-brac, 1882, n.p.).

Although based primarily on works from his collection, Octave du Sartel's book also quotes and reproduces a large number of works belonging to other collectors of his time, which testifies to his integration into the circles of aficionados and interested audiences, not only in Paris, but also in Belgium and England. He thus mentions the collections in Paris of the viscount of Borrelli, of Berthelin, Alfred Beurdeley (1847-1919), Siegfried Bing (1838-1905), Ferdinand Bischoffsheim (1837-1909), Louis Cahen d’Anvers (1837-1922), Henri Cernuschi (1821-1896), Madame Delagrange, Madame Duvauchel, Esnault-Pelterie, E. Hendlé, Léon Fould, Fournier Senior, Paul Gasnault (1828-1898), Admiral Benjamin Jaurès (1823-1889), Léon d'Hervey de Saint-Deny (1822-1892), François Philibert Marquis (1821-1889), Messenger, A Pannier, L. Poiret, Charles Testart, and Sichel; in Brussels, Madame Leroy and Paul Morren; and finally, in London, Georges Salting (1835-1909) and William Graham (1817-1885). Unfortunately, no correspondence has been found to date to give an account of his exchanges, no doubt numerous, with these various collectors.

The absence of footnotes often makes it difficult to trace Octave du Sartel’s sources. Systematically, when it comes to China, the author vaguely mentions "Chinese authors" or "another Chinese author" without specifying the reference work. It is clear, however, that most of these quotations come from the above-named work by Stanislas Julien.

Sales of the Collection

During his lifetime, Octave du Sartel organised a first sale of his collection in April 1882, only a year after the publication of his work. The sale included only porcelain from China (422 lots) and Japan (33 lots), many of which were illustrated in La Porcelaine de Chine. Surprisingly, the sale catalogue does not use the chronological order that he himself had skilfully established, but rather classifies the objects by form (e.g.: vases and bottles, statuettes and pitongs (筆筒, brush pots, etc.). Among the main buyers were art dealers Nicolas Joseph Malinet (1805-1886), Sichel, Siegfried Bing, Winternitz, Fournier, the expert Charles Mannheim, the collectors Édouard André (1833-1894), Ernest Grandidier (1833-1912), Henri Cernuschi, the Marquis de Thuisy (1836-1913), etc., as well as the ceramics museum of Sèvres (AP, D48E3 70). Several lots fetched exceptional prices exceeding 2,000 francs, notably a “rouleau [cylindrical] vase with blue medallions, decorated with designs in gold and leafy scrollwork with large peonies in famille verte enamels, as well as borders that frame the whole" that was acquired by Sichel for 2,000 francs (lot no. 64, AP, D48E3 70). The total sum of the sale was 127,933 francs, which, divided by the number of lots, represents an average of 280 francs per lot, a solid success (Saint-Raymond, 2021, p. 435). It is undeniable that the exhibition followed by the publication of Octave du Sartel's collection had greatly contributed to establishing his reputation among collectors. However, it is difficult to establish the reasons that led Octave du Sartel to part with these objects at that time. It was not a matter of a complete reorientation of tastes, since he did not sell all of his Far Eastern porcelains; in fact he would even go on to buy even more during the major sales of the chocolatier François-Philibert Marquis (AP, D48E3 71). Chinese porcelains still made up part of his daily furnishings at his death. His posthumous inventory lists for example "two lamps mounted in gourds in old China" (AN, MC/ET/VIII/1944).

The will of Octave du Sartel imposed no obligation whatsoever upon his descendants to preserve his collection. The posthumous inventory lists the constraints that would have resulted from its preservation: rental charges for the apartment, interest due to the capital represented by it, remuneration of the staff for its maintenance — substantial charges, to which would be added the risks related to its maintenance (AN, MC/ET/VIII/1944). Therefore, a posthumous sale was organised in two stages, on June 4 - 9, 1894 and then on October 22 - 30 of the same year (AP, D48E3 79).

The posthumous sale gives a completely different image of the objects collected by Octave du Sartel. Chinese and Japanese porcelain (lots 1-121) occupy barely more than an eighth of the works sold on this occasion, to which a wide variety of objects were added: European porcelain and earthenware, illuminated books, Persian miniatures and Indian paintings, paintings (mainly Northern school), drawings, watercolours and engravings, ivory and carved wood, etc. There were even the display cases that had been used to hold the collection in the library of his apartment on rue Lafayette. Among the works sold were also all the overdecorated porcelains that had fuelled the last chapter of his book on counterfeits and imitations (Du Sartel O., 1881, p. 212-227). The illuminated manuscripts testify to the passion of the Sartel couple for illumination. His will tells us that the couple had produced a genealogy of the Du Sartels "written in Gothic characters" by Eugénie and "adorned with miniatures and capital letters" by Octave du Sartel (AN, MC/ET/VIII/1944). It is known that Octave personally restored his illuminated books (cat. sale 04/06/1894, p. 129, n. 1). The posthumous sales catalogue indicates the provenance of certain works (the sales of Paul Morren, François-Philibert Marquis, Escudier, Watelin, Comte de Viel-Castel, Charles Louis, Fournier Père, Bancel, Eugène Piot, L. Decloux, J. Pascal, A. Jubinal, Jitta, Mme d'Yvon, Baron Seillière, Comte de Moisant, Valéro, Hamilton, Fountain, Maillet du Boullay, Lefrançois, Lafaulotte, Baring, Cabert, Marquis d'Houdan, Ploquin, Reybaud , Dr. Raymond, Charles Davillier, Le Beuf de Montgermont, San Donato, Villestreux, Germain Bapst, Spitzer, the Univeral Exhibition, Van Aelbroeck, Arpad, Bérard, etc.). Perhaps this collection reflects the taste of the Frémin du Sartel couple rather than of Octave alone. The sale, made up of 782 lots, would reach a total of 197,776.25 francs (AP, D48E3 79), a number which, compared to the number of lots, remains well below the sale of 1882.

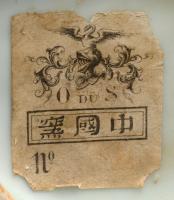

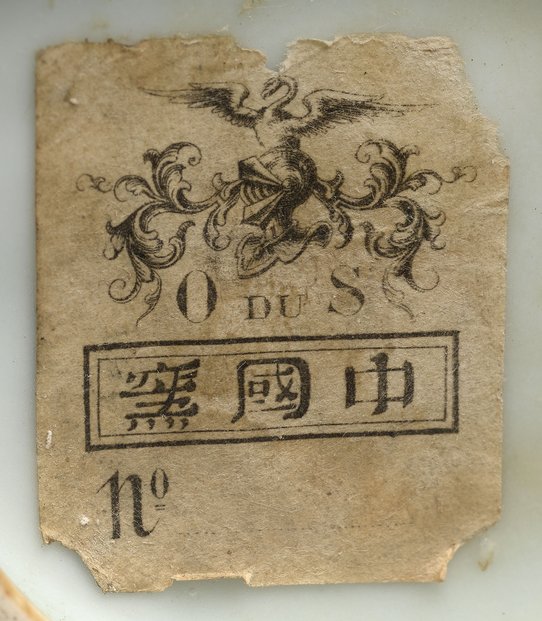

Some works from the Du Sartel collection are now kept in Paris at the Musée Jacquemart-André and the Musée national des arts asiatiques-Guimet, as well as in the Musée des Beaux-Arts of Dijon. The highly detailed label of Octave du Sartel serving as an illustration for this notice will perhaps make it possible to continue the identification of his works in French public collections.

Related articles

Collection / collection d'une personne

Personne / personne