LANGWEIL Florine (EN)

Biographical Article

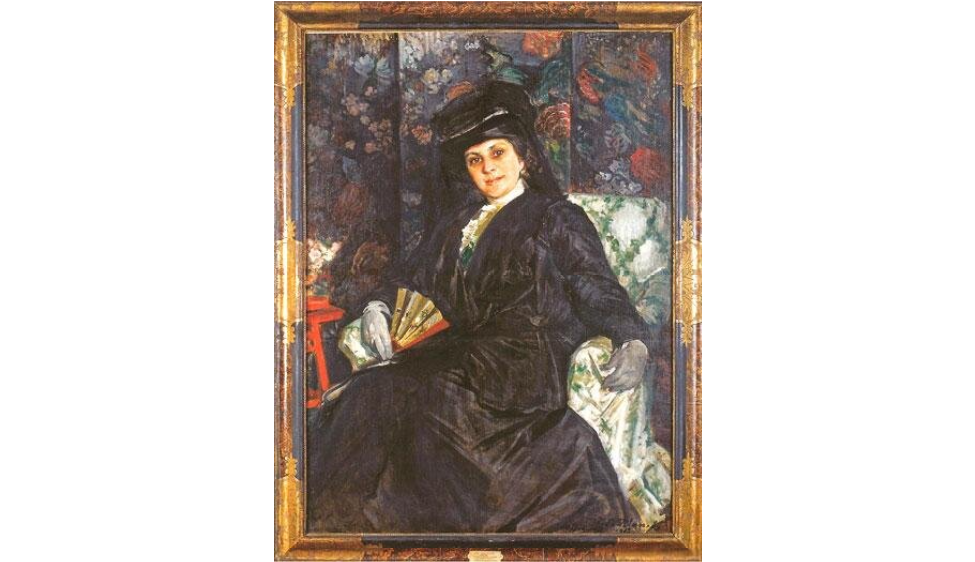

The famous store of Florine Ebstein-Langweil (1861-1958) located at 26, place Saint-Georges in Paris was considered "a true museum" by collectors who came to acquire Chinese, Japanese and Korean objects there (Alexandre A., 1913; Tout-Paris, 1913). Madame Langweil, who was a dealer, expert, collector, and patron, created the Asian collections of the museums of Colmar and Strasbourg and added to those of the Louvre, Guimet, Cernuschi and Ennery museums. In recognition of her numerous gifts, the creation and financing of voluntary associations dealing with the health and education of children as well as the care she provided to the military during the First World War, she was made a Chevalier (1921) and then an Officier (1935) of the Légion d’honneur (AN Léonore, dossier Langweil, 19800035/174/22392). She was also awarded the title of "Curator of the Section of Art Objects from the Far East" in Colmar and at the Strasbourg Museum (AN Léonore, Langweil file, 19800035/174/22392).

Florine Ebstein was born in Wintzenheim (Haut-Rhin) on September 10, 1861 to an innkeeper (Isaac Ebstein) and his wife, Barbe Blum (AD68, Wintzenheim, Naissances 1853-1862, no 112, s.c.). The family settled in Colmar (where his parents died in 1881 and 1884, respectively); Florine went to Paris in 1881 to work in a cousin's pastry shop (Debrix J., 1935, p. 213; Noufflard G.: 1982, p. 62-63). There she met her future husband Karl (known as "Carl" or "Charles") Langweil, pronounced "Langwell", a resident of the neighbourhood. He was Austrian (present-day Czech) by nationality, wealthy, and nearly twenty years her senior (born December 1, 1843). As a "commercial commissar" specialising in "modern knick-knacks" (Debrix J., 1935, p. 213), his name appeared in the 1886 Commerce Almanac Yearbook (Annuaire-almanach du commerce) under the headings "China & Japan" and "Chemisiers". At the Exposition Universelle of 1889, he exhibited "fishing tackle" (group 5, class 43), which corroborates family memories that say he was more interested in fishing trips than in business success (Noufflard G ., 1982, p. 63).

The evolution of the Langweil business can be traced through the correspondence of Émile Guimet (1836-1918). On April 23, 1885, for example, Carl and Florine were living as a couple at 5, rue Saint-Georges (MNAAG, Correspondance, 1885). They were married in London in the spring of 1886 (GRO, Shoreditch, 1c. 244) a few months before the birth of their first daughter, Berthe, on July 5, 1886 (AP, Naissances, 9e, V4E 6169). They then moved to a new home at 9, rue de Provence where they continued to sell items to Guimet using a new letterhead "Carl Langweil. China and Japan. 9, rue de Provence” (MNAAG, Correspondence, October 22, 1887). A few months after the birth of their second daughter, Lucie ("Lily"), on June 13, 1887, they transferred the store to 4, boulevard des Italiens (AP, Naissances, 93, V4E 6173). Madame Langweil signalled this change of address by inviting Guimet to come and inspect their goods (MNAAG, Correspondance, December 1887).

If the Langweil daughters' birth certificates declares Florine "without profession", this is more a matter of social convention than a fair assessment of her business activities. Her correspondence with Guimet clearly shows that she ran the store from 1885: she gave commissions, took care of invoices, attended auctions, and suggested items to customers. Her contemporaries, moreover, noted that she was ahead of her competitors in choosing to focus on ancient Chinese art (Debrix J., 1935, p. 213-214; Kœchlin R., 1930, p. 67-68). Indeed, as early as 1888, the store displayed "second-hand chinoiseries" and paid "the highest prices" for antiques (Bottin, 1888, 1889; Le Petit Parisien, June 28, 1890).

In 1893, Carl abandoned the family and moved to London, leaving his wife with debts and two small children to raise (GRO, St. Giles 1B 554; Noufflard G., 1982, p. 65). Florine, assuming the functions of dealer and importer, learned the antiques trade by trial and error (Debrix J., 935, p. 213-214). Her correspondence with Guimet allows us to follow the transformation of this barely literate young woman into a millionaire merchant who hired a secretary, participated in conferences, became involved in international companies, set up exhibitions, imported Asian objects, appraised objects during sales, and became the patron of various French museums.

All that is known of Carl's activities between 1893 and 1920 is that he sold Chinese and Japanese objects, including books of Japanese prints to the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A), from 1900 to 1901 (C [Collection] V&A, E.1411-1900). In the 1911 British census, he resided at 43 Museum St., near the British Museum, where he worked as an "art dealer" specialising in Chinese and Japanese objects (Census, 1911). He died at the same address on December 12, 1920. His inheritance of £610 went to Florine, although the couple apparently divorced at a date now unknown (NPC, 1920, Langweil; AP, D.Q7 37392, Langweil Estate).

To supply her store, Mrs. Langweil traveled all over Europe and England in search of attractive old objects (Noufflard G., 1982, p. 68-69). In addition, she participated in hundreds of sales at the Hôtel Drouot, where she acquired Japanese and Chinese objects and books (see AP, D60E3/59-62, the minutes of the auctioneer Delestre, for example). She also signed contracts directly with agents on site in China, Korea, and Japan and had excavations carried out (particularly in Shanxi), which enabled her to supply her store with rare and authentic pieces (Debrix J., 1935, pp. 213-214; Koechlin R., 1930, pp. 67-68). To guarantee their quality, she gave agents a percentage of the purchase price (Debrix J., 1935, p. 213-214; Kœchlin R., 1930, p. 67-68).

To better showcase her "treasures", she bought a private mansion at 26, place Saint-Georges, which she inaugurated in 1903. Alexandre described it as "both the museum and the warehouse of everything most rare, venerable, and dazzling that Japanese and Chinese art have produced" (Alexandre A., 1903). “This house-museum of oriental art” was renowned for its ambiance, the freedom with which customers could touch the goods, and its reasonable prices” (Rivière H., 2004; Silverman W., 2018). It not only provided works of art to major collectors and jewellers such as Guimet, Ernest Grandidier (1833-1912), the Rouart brothers, Lord Herbert Kitchener (1850-1916), John Pierpont Morgan (1837-1913), Charles Lang Freer (1854-1919), Henri Vever (1854-1942), and Louis-François Cartier (1819-1904), but also to many international museums: from Boston and Hamburg to St. Petersburg and London (Goerig F., 2005, p. 188).

The catalogue of the "Langweil Collection" sold in London in 1906 (following the bankruptcy of the Scotsman who had bought all the Chinese stock in 1905) gives an idea of both its merchandise and its fame (Willis, 1906; Le Figaro, May 16, 1905). Florine Langweil maintained friendly relations with her clients, explaining to them the origin and history of their objects and offering preferential rates when she knew that pieces would complete a private collection (Rivière H., 2004, p. 93-95; MNAAG, Correspondance). Thus, museum administrators such as Émile Guimet, Raymond Kœchlin (1860-1931), and Louis Metman (1862-1843) asked her to encourage individuals - and especially major collectors such as Bertha Potter Palmer (1849-1918 ) and Suzanne Poirson Girod (1871-1926) – to lend objects or make donations to their establishments (MNAAG, Correspondance, letters of November 21, 1892 and May 22, 1908).

Florine Langweil took part in all the exhibitions of Asian art organized by the Musée des Arts décoratifs from 1909 to 1914. The file of the Chinese Exhibition of 1910, in particular, contains numerous letters which show how she helped her colleagues to evaluate and date objects and to convince other collectors to participate (UCAD, sD1/53, dossier Exposition chinoise de 1910). This work was not always publicly recognised; the catalog of the Chinese Exhibition, for example, only documents its loans. On the other hand, from 1910, she began to mount her own exhibitions, thus establishing her reputation as an expert. The Chinese paintings that she exhibited at Durand-Ruel from January 9 to 13, 1911, dazzled Parisians who were delighted by the talent of the "medieval" Chinese painters (Mouney G., 1911; Durand-Ruel, 1911). Alexandre identifies her as the initiator of a fashion, "the High Priestess of this new cult for such an ancient art [...] the enthusiastic and enlightened agent of this magnificent demonstration" (Alexandre A., January 9, 1911). Another sale exhibition at Durand-Ruel, from December 5 to 30, 1911, introduced other Chinese artists from the Song dynasty (960-1279) to the Qing dynasty (1644-1911): more than 100 paintings were exhibited there, to which a room devoted to old screens in polychrome lacquer, known as Coromandel was added (Tchangyi-Tchou and Hackin J., 1911; Alexandre A., December 5, 1911; Möller T., 1912, p. 159-161). From 1911, antiquities from the "Langweil mission" would be exhibited at the Musée Guimet alongside objects from the excavations of Paul Pelliot (1878-1945), Édouard Chavannes (1865-1918), Jacques Bacot (1877-1965), Jacques de Morgan (1857-1924) and Émile Goubert (1852-1909) (Le Figaro, May 17, 1911). Madame Langweil now officiated as an expert during sales, such as the three-part sale of her client Alexis Rouart (1839-1911) in 1911 (Langweil F., 1911), and regularly participated in exhibitions of Chinese art organised in the Cernuschi and Guimet museums.

The news that she would close her store in 1914 to take a trip to China affected her customers, who spoke of "the end of an artistic dream" (Alexandre A., 1913). Florine Langweil sold her business to the Chinese Company Tonying, chaired by a certain Tsang-Feu-Tshié (Le Figaro, May 25, 1914). Unfortunately, the outbreak of World War I prevented Mrs. Langweil from making the long-desired trip to Asia. She continued, however, to work as an expert and to make regular donations, notably to the Musée Cernuschi, where she held the position of vice-president of the Society of Friends from its foundation in 1922 (BMVP, August 26, 1923). Hundreds of articles in Le Figaro, Le Gaulois and Comœdia allow us to trace her cultural prominence: from 1909 she lent objects for almost all the exhibitions of Asian art in Paris. During the First World War, she transformed her private mansion located at 61, rue de Varenne, into a museum, mounting exhibitions for "La Renaissance des foyers en Alsace" (May 5 – June 20, 1916; November 22-23, 1917), the profits of which were devoted to soldiers and war orphans (Petrucci R., 1916).

Increasingly known for her good works, and in particular for the creation of a "Prix de français en Alsace" in 1923, she continued to participate in exhibitions such as the International Exhibition of Chinese Art, which took place in London from 1935 to 1936. Her militancy against the Germans, participation in the Israelite Alliance, as well as the opulence of her house-museum located at rue de Varenne undoubtedly explain the seizure of her collection by the Germans during the Second World War (returned almost intact by the Commission consultative des Dommages et des Réparations in 1949) (Noufflard B., 1982, 82). Her family survived by fleeing Paris to settle in Toulouse, in the Dordogne and then in Normandy, with falsified papers to conceal their Jewish identity (Noufflard B., 1884, p. 81-82).

Until her death in 1958 (December 22), Florine Langweil continued to collaborate with leading figures of twentieth-century Asian art, including her friend Ching Tsai Loo (盧芹齋) [1880-1957] and Raymond Kœchlin (Noufflard B., 1982; Emery E., 2016).

CC BY-NC-SA

The Collection

It is impossible to inventory the collection of an art dealer who owned, exhibited and shared several million objects over a period of 75 years. Already, in 1913, 45 years before her death, the art critic Arsène Alexandre (1859-1937) noticed the extent of her activities: "For thirty years, Madame Langweil, alone, everything passing through her hands, all the most demanding connoisseurs dealing only with her, has imported millions of Japanese, Korean, and Chinese works of art, with impressive confidence and prescience" (Alexander A., 1913). The National Archives record the occasional donations of Japanese and then Chinese objects made by Madame Langweil and accepted by the Musée du Louvre (Chinese stelae and sculptures, for example; AN, 20144787/16). The Le Bulletin municipal de laVille de Paris, the archives of the museums of Decorative Arts, Guimet, Ennery and Cernuschi allow us to trace others. This summary will therefore focus on the best known elements of her collection.

After the liquidation of the store located on place Saint-Georges, Ms. Langweil especially favoured the Alsatian museums (in Colmar, Strasbourg and Mulhouse), which were then poorly provisioned with works of art. Her donations to the Unterlinden Museum give an idea of the works she considered the most important: Japanese tsuba, kodzuka, inrô and makimono dating from the 15th to 18th centuries, vases and mirrors from the Han period, other Chinese objects (paintings, statuettes and tiles from various periods), as well as Chinese and Japanese albums from the 17th and 18th centuries (Goerig F., 2005, p. 187; MU 1C2/2, Registre des dons 1887-1927). She offered around a hundred disparate Japanese and Chinese objects to the Strasbourg Museum: Chinese incense burners from the 15th to the 18th century, a mirror-holder unicorn from the Ming period (1368-1644) and a mirror from the Han period, Japanese vases, and 30 kakemono and books (MDS, don Langweil). She further enriched Alsatian museums by donating modern paintings, Asian objects dating from life in the 17th century, and a rare collection of Japanese prints estimated in 1920 at 500,000 francs, which would be exhibited in three rooms of the Strasbourg museum (MS, Don Langweil, letter of May 3, 1920; Le Figaro, April 4, 1920). At the Unterlinden Museum, a "Langweil Room" was created in July 1923. Since 1962 this has no longer existed, but a catalogue makes it possible to understand the installation designed by Madame Langweil herself (Waltz J., n.d.).

In a 1935 interview, Jean Debrix evoked the richness of her personal collection, exhibited on the ground floor of the house located at 61, rue de Varenne: "three huge salons" filled with "monumental statues", display cases, rock crystals, porcelains, lacquers, ivories, and kakemono, all crowned by two Coromandel screens from the Kangxi period were considered to be the masterpieces of her collection (Debrix J., 1935, p. 213). One of these screens, which depicts the arrival in China of the first Dutch, is today in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam (R, BK-1959-99) and the other in the Musée Guimet (bequest of Mme Langweil; MNAAG, MA2137). With the exception of a few other donations (notably a biscuit bowl from the Kangxi period worth 22,000 francs to the Strasbourg museum and a white and blue vase from the Ming period estimated at 44,000 francs to the Unterlinden museum), her collection of 499 objects was dispersed from June 4 to 6, 1959 for the total sum of 36,038,745 francs (AP, D.Q7 37392, Succession Langweil Collection de Madame Langweil, 1959). Her contemporaries fully appreciated the person who made ancient Chinese art known in France: "If one day women should enter the institute, Madame Langweil would have all the qualifications to be admitted among the members of the Académie des Beaux-Arts” (Alexander A., 1911).

Related articles

Personne / personne

Collection / collection d'une personne