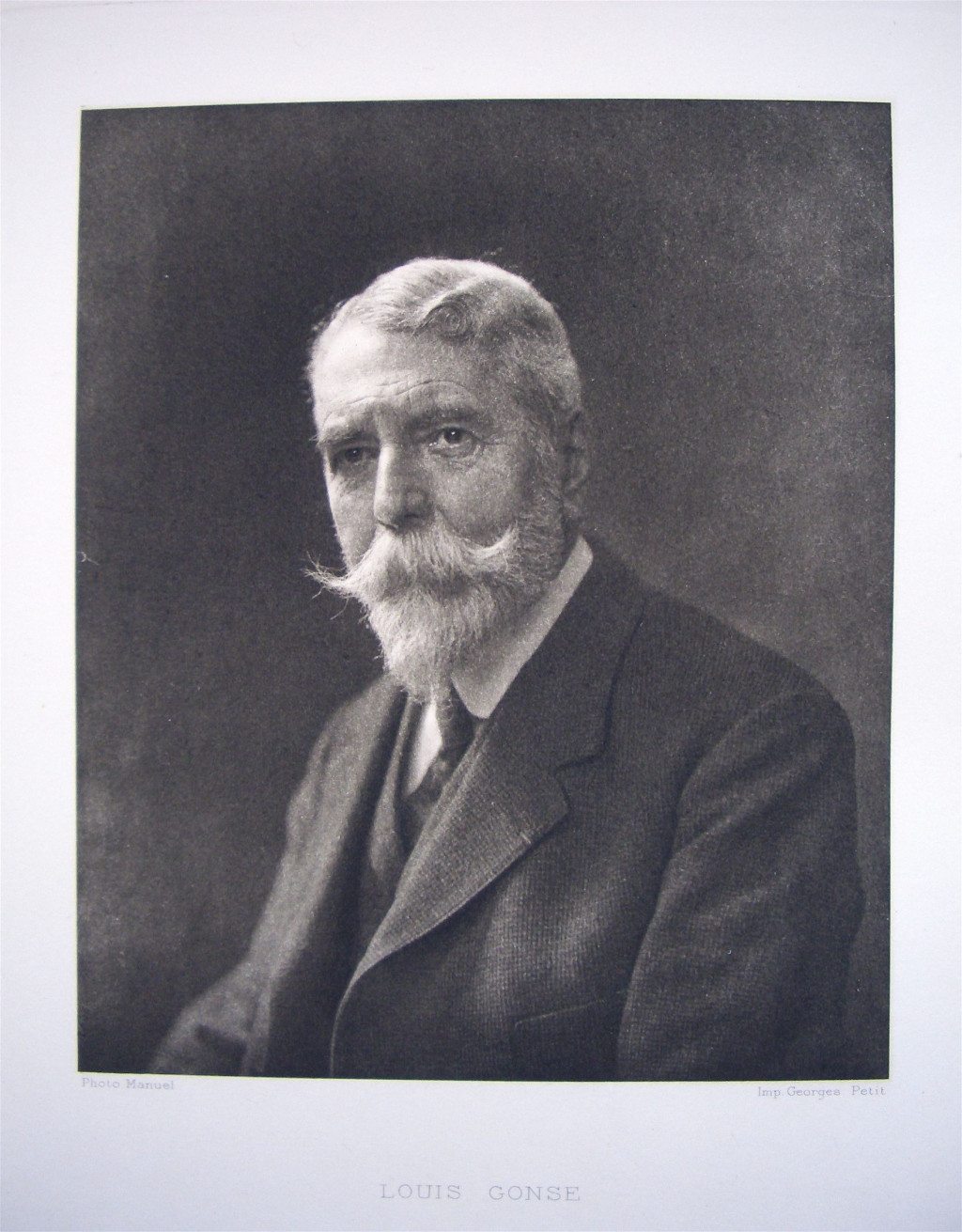

GONSE Louis (EN)

The genesis of a historian and connoisseur

Louis Gonse was born on 16 November 1846 in Paris. He died in the same city on 19 December 1921. The son of Emmanuel Gonse, a counsellor at the court of Rouen, he studied law between 1865 and 1870, while attending courses as an auditor at the École des Chartes. In his youth, he travelled widely in France, Germany, Italy, and Algeria. From these came his first writings, travel stories, and critiques of Salons. But it was while attending the École des Chartes, where he established friendships and earned the admiration of several of his confrères, that he began to truly consider the idea of becoming an art historian.

It was here, in particular, that his taste for French Gothic art and for European ‘primitives’ began to emerge—which influenced his later interest in Japanese art; he always highlighted the ‘close relation’ between the latter and ‘thirteenth-century French art’ (Gonse, L., 1883, Vol. 2, p. 89); here again he passionately defended the French heritage—with regard to both historical monuments and museum collections—and he convinced himself of the great value of objects in establishing a history of art, and, above all, he was part of a milieu that enabled him to rapidly acquire a certain respectability in the world of writers on art. He was under the age of thirty, in February 1875, when he was appointed Editor-in-Chief of the Gazette des Beaux-Arts, a French review of critiques and the history of art. His work at the head of this famous scholarly publication was remarkably bold and adroit. Alongside the traditional orientation of an organisation that prioritised the study of the classical European art of the Renaissance, he introduced new horizons—non-European arts, decorative arts, and non-academic French art—, which he succeed in making acceptable through the conscientiousness with which he implemented their presentation and defence.

It was only during the 1878 Exposition Universelle, in Paris, that the desire to highlight non-European arts truly emerged, and Louis Gonse paid tribute to them at the beginning of the two large volumes that contained all of the articles published by the Gazette about the Exposition: here, he underlined the quality of the Chinese, Japanese, Algerian, and Persian pavilions, and so on, and admired ‘the unprecedented accumulation of artistic treasures from the Far East’ (Exposition Universelle de 1878, 1879, p. 16). His articles or those of his friends—such as Lucien Falize (1839–1897), Paul Mantz (1821–1895), Ernest Chesneau (1833–1890), and Louis Duranty (1833–1880)—often combined historical overviews with the description of the forms, but they were primarily motivated by a combat that Louis Gonse undertook and which soon culminated in Art Nouveau: ‘Attempt to renew the styles of the epochs of naivety and invention, by adapting them to our uses, tastes, and needs.’ (Exposition Universelle de 1878, 1879, p. 340), and thereby breathe new life into French decorative art in the face of its British and German competitors.

An all-consuming passion for Japanese art

It was in October 1883, several months after holding a Exposition rétrospective de l’art japonais (held at the Galerie Georges Petit, Paris, April–May 1883), that Louis Gonse published the two heavy and luxurious volumes of L’Art japonais, with its thousands of illustrations, and its re-edition in a more manageable and popular form, in 1886, 1891, 1900, 1904, and 1926, its translation into English in 1891 and Japanese in 1893. The passionate debates provoked by this book and the many articles that Louis Gonse wrote himself subsequently all underlined the significance of the event, whether amongst scientists, collectors, dealers, artists, or decorators.

Louis Gonse’s love of Japanese arts had a powerful effect on opening up and orientating his view of the painting and decorative arts of his era. This was the very core of his life for almost a third of a century, between 1873 (when he showed the first signs of enthusiasm after reading a report of the ‘Exposition Orientale’, in which the Cernuschi Collection was exhibited in the Palais de l’Industrie) and 1902 (the date of his last article about Japanese art). Here again, his writings only make sense in the context of his participation in a milieu of collectors within which he played a leading role.

This is evident in the tribute paid to him by Raymond Kœchlin (1860–1931), one of his allies in the same combat, at the beginning of his own book of souvenirs published in 1930: ‘no one was more qualified than he [Louis Gonse] to write this chapter in the history of curiosities. Even if he wasn’t one of the very first collectors who, in around 1860, frequented the shops where Japanese objects began to appear—he was only a child at the time—, he subsequently met these pioneers and shared their enthusiasm as debutant collectors; the collectors of the second generation, circa 1890, had all been his friends or pupils’ (Kœchlin, R., 1930, pp. 1–2).

From this perspective, Louis Gonse might be considered as the almost perfect historian and connoisseur, for whom historical investigation was inseparable from the definition and defence of an aesthetic outlook and whose quest was fundamentally based on direct contact with monuments and works. Often, this priority accorded to the visual was done so to the detriment of book-based scholarship. With regard to this he was subjected to the inflamed criticism of the other major international specialist in Japanese art at the time, Ernest Fenollosa (1853–1908): from Japan, where he moved in 1878, the American heavily criticised the ignorance, in his opinion, of Louis Gonse’s views with regard to Japanese painting that preceded the Edo period, his valorisation of the vulgar school of prints, and, above all, the theory that excluded the influence of China as the explanatory factor behind Japanese painting (Fenollosa, E., 1884).

An innovative approach to Japanese art

The first goal of the director of the Gazette was to give Japanese arts a historicity that had hitherto been ignored not only by the general public, but also by a whole group of connoisseurs of Japanese art, such as Edmond de Goncourt (1822–1896), who, for this reason, never stopped mocking the erudite pedantry of his own contradictor: ‘Amongst the collectors of japonaiseries, there is an insupportable and pretentious person, a foolish sheep, who goes by the name of Gonse’ (Goncourt (de) E., and J., Journal. Mémoires de la vie littéraire, editions Robert Ricatte, 1956, Thursday 25 January 1883, p. 231). Louis Gonse’s second major aim was to prove that Japanese art was a national art, which had certainly been influenced by other arts but which did not owe these influences its own identity as a whole nor even its most distinct developments—which led him to serious misinterpretations. He also developed a deliberately racialist approach, following in the wake of Ernest Renan (1823–1892) and above all Hippolyte Taine (1828–1893), and associated as often as possible the artistic ‘genius’ of this people with Indo-European roots, using obscure arguments about migratory flows and the anthropological characteristics of the different populations living side-by-side in the Nippon Archipelago.

Lastly, and most importantly, his own aesthetic approach to Japanese art was based on an important belief that was almost obsessive in his writings: ‘The Japanese are the best decorators in the world’ (Gonse, L., 1886, p. 1). This belief, stated at the beginning of the first edition of his own book (and which he constantly insisted on thereafter), had a dual purpose: first of all, it enabled him to underline the radical heterogeneity of the Japanese vision compared with Western vision and the need to address it seriously, to ‘destroy racial prejudice, and the acquired taste that leaves us dubious before the manifestations of a new aesthetic’ (Gonse, L., 1886, p. 3). Then, it led him to promote the idea of the unity of artistic inspiration, in which ‘what we call the minor arts form a whole that is inseparable from the fine arts’ (Gonse, L., 1886, p. 61), and a ‘minuscule netzké [sic]’ with ‘the ornamentation of a temple’ (Gonse, L., 1886, p. 131). However, this unity was always established under the aegis of painting, considered as a major art in the Western sense of the term: ‘the history of painting is, in Japan more than anywhere else the history of art itself. (…) Painting is the key; without it, our eyes remain deprived of everything. All art comes from this and is subordinate to it’ (Gonse, L., 1886, p. 5).

This led to a conception of the decorative that was both strategically skilful and aesthetically innovative: the decorative, delivered from its lower condition in the Western hierarchy of the arts, became a notion in itself, not characterising a form of creation but rather a general conception of the image, to which painting is not only indebted, but of which it is the conceptual matrix.

A last section of Louis Gonse’s works was devoted to masterpieces in French museums, a series of weighty volumes, the last of which was published in 1904; he aspired to succeed Clément de Ris (1820–1882), all the while emphasising a demanding form of the vulgarisation of luxury, with nationalist overtones. Lastly, during the last fifteen years of his life, he sacrificed both his collecting and writing activities, while devoting himself to the militant activity of heritage administration: this involved his work with the Conseil Supérieur des Beaux-Arts, the Conseil des Musées Nationaux and, as of 1913, the Commission des Monuments Historiques. In the latter case, Louis Gonse sought—with the backing of loyal allies such as Gaston Migeon (1861–1930) and Raymond Kœchlin—to stimulate and renew the acquisition policies of the major museums (he is often attributed with the addition to the Louvre collections of the Grande Odalisque by Ingres in 1899, amongst many other examples), as well as to classify and restore objets d’art that were part of the national heritage. In doing so, he was not merely reflecting his times, attempting to conquer new fields in the history of art and develop new approaches, through his in-depth appreciation of the objects and the racial-national generalisations that were as vast as they were ambiguous; in his cautious way, he was also a committed individual, who was more often enthusiastic than pessimistic, and never disenchanted, whose finest texts still constitute a remarkable defence and an example of a subjective viewpoint in the history of art.

A collector and connoisseur

To organise his own retrospective exhibition of Japanese art and his book about Japanese art in 1883, Louis Gonse persuaded Wakai Kenzaburo (1834–1908) to bring from Japan, for the purposes of study, an ensemble of kakemono believed to be anterior to the Edo era and exceptionally loaned by Japanese collectors (even if those that Louis Gonse thought were originals, particularly by Kanaoka, the founder of the Kosé School in the ninth century, were in fact merely copies or late pastiches).

As an amateur, Louis Gonse himself adopted a certain approach to collecting Japanese arts, and his choices were not dictated by simple visual pleasure, but rather by an encyclopaedic desire to gain knowledge about all the techniques and periods of an art whose origins—in contrast with the opinion of the Goncourt brothers—he traced ‘back to ancient times, in the seventh century CE’ (Gonse, L., 1883, Vol. 2, p. 192).

Louis Gonse was neither a scholarly Japanologist nor a travelling ethnographer, nor really a Western follower of Japonisme, or even purely and simply an aesthete, but rather a connoisseur, whose activities were motivated by the desire to create a history of art via and for objects. L’Art japonais is something of a guide for the amateur, or, to borrow the expression of Ary Renan (1858–1900), a ‘great documentary herbarium’ (Ary, R., 1884, p. 6), with his accumulations of artists’ names (accompanied most often by the reproduction of their ideograms to facilitate their identification) and his detailed technical descriptions (in particular of the bronze and lacquer pieces) as well as his peremptory assertions about taste, often followed by pedagogical comparisons between such and such Japanese artist and European artist: for example, Fra Angelico (1400?–1455) and Kanaoka, Corot (1796–1875) and Motonobu (1476–1559?), and Rembrandt (1606–1669), Callot (1592–1635), Goya (1746–1828), and Daumier (1808–1879) for Hokusai (1760–1849).

Hence, in Europe, he became prominent as the particularly experienced and influential spokesman for a general movement that, in about a quarter of a century after the country had opened up to the West, led to the incorporation of Japanese arts into the collections of Western museums. While doing this his own work was motivated by the nationalistic desire to make up for France’s lack of development in the field of research compared with England and Germany. For example, he wrote in the catalogue foreword of his own retrospective exhibition in 1883 (Gonse, L., 1883, pp. 5–6) ‘There persists in France a regrettable indifference [with regard to the issue of Japanese art], while abroad—in Germany, England and, above all, America—its inspires enormous interest’.

Overall, Louis Gonse had a performative conception of the history of art, which involved both gaining knowledge and renewing the creative process, not through the imitation of forms, but by their transposition and their adaptation according to certain transcultural principles. Amongst these principles, the main one was the notion of ‘decoration’, which he was unable to define consistently: on the one hand, he juxtaposed the decorative ideal of the primacy of ‘sensorial pleasure’ with intellectualism (Gonse, L., 1888, p. 12), while claiming that an artist’s ‘intellectual education’ enables him or her to ‘shift from the sensation to the idea’ (Gonse, L., 1884, p. 150); and, on the other hand, he associated decoration with the notions of ‘synthesis’ and ‘simplification’ (Gonse, L., 1883, p. III), while insisting on the importance of ‘naturalism’, via the faithful imitation of forms and nature (Gonse, L., 1890, p. 371). He also defended a functionalist form of aesthetics, placing the essence of the decorative in the ‘logical’ adaptation of works to a social use and unity between the arts—but he still continued to isolate and highlight the major arts of painting, sculpture, and architecture, compared with the role of the minor arts in daily life.

Louis Gonse’s collection

Louis Gonse believed that it was absolutely vital to see and handle Japanese objects to gain an understanding of Japanese aesthetics. François Gonse, in the series of remarkable works he dedicated to his ancestor, believed that the starting point for this collection was at some point between 1873 and 1875—a process that continued until 1904 (Gonse, F., 1996, p. 484). Hence, objects that came from various collections, listed in L’Art japonais, were for Louis Gonse ‘investigative tools that were both scientific and aesthetic’ (Gonse, F., 1996, p. 2). Working closely with the main Parisian dealers in Japanese art, such as Wakai Kenzaburo, Hayashi Tadamasa (1853–1906), and Siegfried Bing (1838–1905)—who wrote the chapter on ceramics in the first edition of L’Art japonais—, Louis Gonse initially compiled an exceptional personal collection, as attested by the thousands of works inscribed in the catalogues of the posthumous auctions that were held between 1924 and 1988. The three first sales of 1924 alone comprised 2,656 lots.

His collection of Japanese art (around three thousand articles) was described as follows by François Gonse: ‘The Gonse Collection in 1883, in the Galerie Petit and in L’Art japonais, is a summary in itself of the research, tastes, and preoccupations of all of the French and Western collectors in the 1880s. This collection is without doubt the most diverse of all the French collections of the era and the most balanced in the number of objects per category’ (Gonse, F., 1996, p. 484).

In April 1883, of the 3,500 objects exhibited in the Galerie Georges Petit on the Rue de Sèze, Louis Gonse owned 1,183 of them; 358 were mentioned in L’Art japonais, of which 290 were also reproduced. He also owned at that time 108 paintings (including 66 Kakemono, 6 screens, 3 painted fans, 8 makimono, 27 albums and 50 Japanese prints). In addition, he owned 70 sculptures of various kinds (including 29 bronzes), 172 netsuke, 177 lacquer objects, 20 weapons and a (mempo) visor, 138 tsuba, 81 kozuka, 43 pipe cases, 73 fabric items (including 33 fukusa), 131 ceramic wares, and 140 objects of various types (Gonse, F., 1996, p. 484).

In addition, Gonse’s racial beliefs about the Indo-European roots of the Japanese people led him to take a pioneering interest in Persian and Mongolian Islamic arts. Like his friend Duranty, he systematically associated them with those of Japan, with the conviction that he could ensure that both with regard to the Arabs and the Japanese, the ‘major civilising centre of Asia’ (Gonse, L.,1886, p. 36) was ancient Persia. This resulted in him becoming one of the very first collectors in Europe to assemble a remarkable collection of Mongolian and Persian miniatures, which he exhibited in Paris in 1893 and, once again, thanks to his friend Gaston Migeon, in the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in 1903.

Related articles

Personne / personne

Collection / collection d'une personne