ARIEL Édouard (EN)

Biographical article

Édouard-Simon Ariel, son of Simon Ariel and Victoire-Aglaë Gautron, was born in Nantes (Loire-Atlantique) on October 5, 1818 (AD 44, 96 J 7). His father, Simon Ariel (born September 10, 1772), was lieutenant of royal customs in Nantes (AD 44, 96 J 6). This position, connected with the city’s port, provided a window onto faraway lands that was rare at the time. The influence of this setting and the interests of his family naturally guided Édouard Ariel towards a career in the Navy. From August 1, 1836, he was an attaché in the administrative service of the port of Nantes, as a Navy scrivener (écrivain de la Marine) (BnF, Indien 1061, f. 8ro). He served in this role until December 7, 1840, when he became attaché to the central administration of the mayor of Paris (BnF, Indien 1061, f. 9ro). He was named Navy clerk second class (commis de la Marine de deuxième classe) on December 24, 1840; about four years later, on February 10, 1844, he was promoted to Navy clerk first class (commis de la Marine de première classe) (ANOM, EE 40/12). On April 3 of the same year he was assigned to Pondicherry and on June 13 he embarked from Brest (BnF, Indien 1061, f. 9ro).

On November 19, 1844, after five months at sea, Ariel landed at Pondicherry (BnF, Indien 1061, f. 9ro), whereupon he launched a career in the colonial administration of the French establishments in India. He was named secretary of the archives (secrétaire archiviste) for the governor Louis Pajol (1790-1855) by a provisory decree of nomination on February 24, 1845. This nomination was confirmed on April 28, 1847 (AD 44, 96 J 7). Over the years, he assumed various roles: on January 5, 1846, he was named conservator of the public library of Pondicherry; on December 31, 1852, having received the title of assistant commissioner of the Navy (aide-commissaire de la Marine) on December 23 1847, he was called upon to oversee provisions, commissioning of provisions, construction sites, and studios (AD 44, 96 J 7). Furthermore, by an order of January 15, 1849, the new governor, Hyacinthe Marie de Lalande de Calan (1802-1850), designated Ariel to preside over the electoral bureau of Bahour, starting January 22 that year (AD 44, 96 J 7). A letter from the archives informs us that since July 1852 Ariel had dropped the role of secretary of the archivesand had been replaced by a certain Chauvet de Cavrolais, In the same letter, dated August 4, 1852, M. Le Peltier suggests that the governor hire him as a personal secretary (AD 44, 96 J 7). We do not have information on the duties that Ariel performed in the colonial administration in Pondicherry in 1852, but we know that he rose in rank and became under-commissary of the Navy (sous-commissaire de la Marine) on March 21, 1853 (ANOM, EE 40/12). December 31 of the same year he was established in his previous functions of secretary of the archives in the government (BnF, Indien 1061, f. 15ro). It is around this time that he must have fallen ill; according to Léon de Rosny (1837-1914), “the doctors declared that he had no chance of recovering his health unless he returned to Europe; but Mr. Ariel did not wish to leave India before having completed his research. Despite his illness, he set to work with greater fervour than ever, hoping thus to hasten the moment of his departure for France. But it only worsened his situation; and on April 23, 1854, death compelled him to give up all his hopes” (Rosny L. de, 1868, p. 177, n. 1).

In tandem with his official career, Édouard Ariel had throughout his life also pursued a career of scholar and orientalist. From an early age, he was interested in poetry, literature, history, and medicine. This is attested to by papers that remained in the possession of his family, today preserved in the departmental archives of the Loire-Atlantique (AD 44, 96 J 7). There one finds, for example, numerous poems dedicated to his mother, as well as recipes for producing an “elixir of long life” and other remedies. Ariel may have already begun to frequent the circle of Orientalists during the period from 1840 to 1844, which he spent in Paris before his departure for India. He seems to have studied under the direction of Eugène Burnouf (1801-1852), a French linguist and scholar of India, as well as a founding member of the Société Asiatique in 1822.Shortly after his arrival in Pondicherry, Ariel struck up a scholarly correspondence (BnF, Indien 1061, f. 11ro) with Burnouf, whom he addressed as “Dear Professor” (Ariel E., 1848, p. 416). This special relationship would also seem to explain Ariel’s close link with the Société Asiatique: he published all his research in their journal and bequeathed his library to them after his death. Certain details of this donation are known to us through two letters from Gallois Montbrun, executor of Édouard Ariel’s will, sent to the notary Auguste-Julien Aubert of Nantes who took care of the Ariel family's business. In the first, dated February 23, 1855, Montrun writes to Aubert: “[…] following the liquidation of Ariel’s inheritance, tomorrow I will load 15 packages for the family and the Asiatic Society onto the Frimaquet, which sets sail for Bordeaux in a few days. Please have the kindness to open an insurance policy for a sum of six thousand francs (5,500 for the collection for the Société Asiatique and and 500 for possessions for the family).” A second letter from Montbrun to Aubert dated March 10, 1855 explained the matter of Ariel’s financial inheritance, which was to be used principally for the education of his daughter Marie, whose mother was a Tamil woman named Ellammal (AD 44, 96 J 7).

Whatever the case, shortly after his arrival at Pondicherry, Ariel became interested in the history, architecture, language, and literature of the region, as demonstrated by the various papers today conserved at the Bibliothèque nationale de France (NAF 8883-8941, Indien 160-168). Above all, Ariel was fascinated by the Tamil language, in which he acquired an exceptional mastery which allowed him to pass a difficult competition. Julien Vinson (1843-1926) informs us that the “colonial government had established by two decrees of February 28, 1843 and August 12, 1849 a bonus of 2,750 Francs (1,500 English Rupees) for the ‘study of native or oriental languages,’ Hindustani, Tamil, and Telinga. This bonus, given after an oral and written test of the greatest seriousness, has until now been conferred only five times: [...] on April 27, 1850, by M. Ariel […]” (Vinson J., 1879, p. 21). By a resolution of the counsel of administration of the French establishments in India and Pondicherry dated August 20, 1851, which awarded the bonus to Ariel, we learn that the competition included no less than nine tests: “1. Exercise, Tamil grammar; 2. Oral reading and translation of Tamil works in prose; 3. Taking dictation in Tamil; 4. Oral translation into French of a request in Tamil and conversation in this language with the petitioner; 5. Deciphering difficult writing in Tamil; 6. Written translation of a prose passage in Tamil and of minutes in this language concerning territorial revenues; 7. Translation into Tamil of a judgement; 8. Establishment of an account in Tamil and translation of another account into Tamil and French; 9. Writing an official letter in Tamil” (AD 44, 96 J 7). His early death prevented Ariel from sharing his prodigious knowledge with a wide public, as notes Gallois Montbrun in his obituary (Gallois Montbrun A., 1854). He nevertheless published three important studies, with translations, on the Tirukkuṟaḷ (திருக்குறள்) of Tiruvaḷḷuvar, a classical text of Tamil literature, in the Journal de la Société Asiatique (Ariel E., 1847, 1848, 1852).

The collection

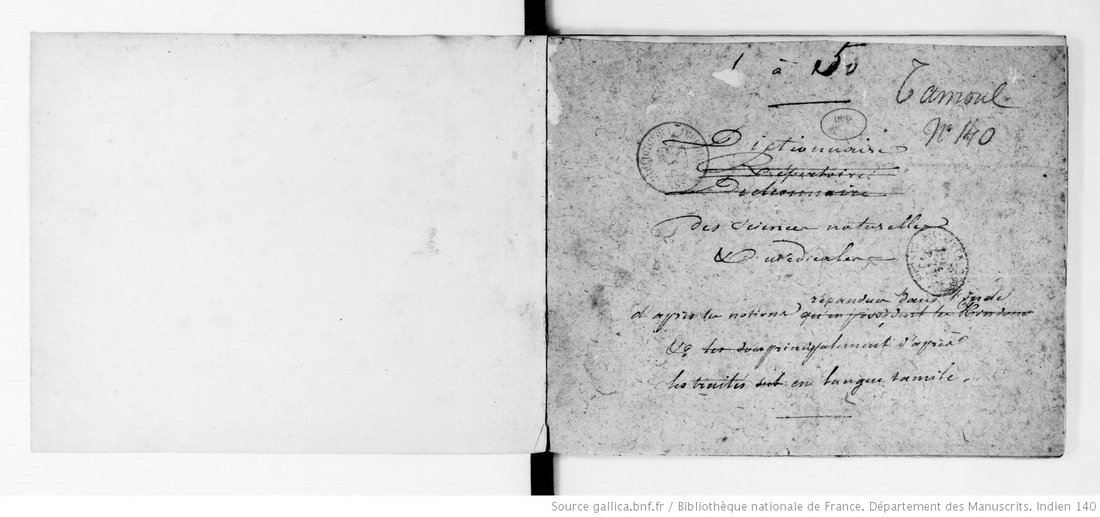

The collection of Édouard Ariel consists principally of Indian manuscripts and of books printed in India. The majority is in the Tamil language, but there are also some works in Sanskrit and other South Asian languages. In addition, his collection includes objects such as coins and statuettes, as well as various notes.

The collection was assembled between 1845, when Ariel arrived at Pondicherry (November 19, 1844, precisely; see BnF, Indien 1061, f. 9ro) and 1854, when he died of illness. Therefore, the majority of the objects come from the present-day state southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu.

In his will, Ariel donated his library (manuscripts and printed books) to the Société Asiatique in Paris (Rosny L. de, 1868, p. 177). He had first intended to bequeath this legacy to Eugène Burnouf (1801-1852), but upon learning of his death, he opted for the Société Asiatique (Rosny L. de, 1868, p. 224). On October 12, 1855, a commission composed of Joseph Garcin de Tassy (1794-1878), Édouard Lancereau (1819-1895) and Léon de Rosny was assigned by the Société Asiatique to make a report on the content of the thirteen crates of the Ariel donation (Finot L., 1922, p. 51; Rosny L. de, 1868, p. 178).

In 1868, Léon de Rosny published an excerpt from this report (Rosny L. de, 1868), which also contains bibliographical data collected subsequently (Rosny L. de, 1868, p. 178, n. 1). The report also provides an unevenly detailed description of the printed books (p. 179-191), manuscripts (p. 191-223) and artifacts (p. 223-224). Rosny distinguishes several types of manuscripts without systematically indicating their number (Rosny L. de, 1868, p. 191-193), namely 1. Tamil manuscripts engraved on palm leaves; 2. Tamil manuscripts written in ink on paper (24 volumes of several formats and 10 other volumes, which raise the question of whether they should be included among Ariel’s papers), 3. Manuscripts in languages of India other than Tamil, 4. Ariel’s papers(handwritten notes, correspondence, recopied fragments of work; in total 500 bundles). Since Rosny was unable to read Tamil, he concentrates on Ariel’s papers, from which he quotes excerpts, and provides the most detailed listing of the artefacts to our knowledge (Rosny L. de, 1868, p. 223-224). Among them are statuettes made from various materials (wood, bronze, alabaster, and ivory) that represent divinities, people, and animals, as well as objects from daily life (a bracelet, a bottle, prayer beads, bells).

This donation by Ariel raised questions within the Société Asiatique that were recorded in the minutes from its meetings (Finot L., 1922, p. 51-54): should the society keep the manuscripts? In the case of the Ariel donation, discussions resulted in their dispersal, contrary to his wishes (Finot L., 1922, p. 52). Eventually, the society decided to give the manuscripts and papers to the Bibliothèque impériale, today the BnF (Finot L., 1922, p. 54). Register B of the donation to the BnF, no 1192, dated August 1, 1866, records the donation by the “Société Asiatique de Paris” of “1o Three hundred twenty-four Tamil manuscripts on palm leaves; 2 o a Tibetan manuscript containing different parts of the Kandjour; 3o a manuscript in Nepalese script; 4o Different papers, excerpts, studies, etc., of M. Ariel.”

In the absence of a detailed description of Ariel’s manuscripts in the report by Rosny or in the register of the BnF, we are not yet able to identify all his manuscripts present in the BnF collections. A number of the Tamil manuscripts could be identified thanks to the catalogue by Cabaton (Cabaton A., 1912), itself based on a still-unpublished account by Vinson (Vinson J., 1897-1868), which mentions the manuscripts’ provenance. Most of Ariel’s manuscripts on palm leaf (identified for the most part under the BnF call number “Indian”) have the particularity of bearing a title page in another hand that indicates the content of the manuscript as well as a call number in a system of classification by letter and number. A likely hypothesis is that Ariel, likely not skilled in the technique of incision on palm leaf, ordered these title pages from an Indian copyist. It remains to determine whether they were created before the acquisition of the manuscripts, as part of a systematic plan of acquisition of Tamil texts (the contents of the title page and the manuscript do not always correspond exactly; certain title pages have been corrected), or afterwards (the format of the title pages corresponds in general to that of the manuscript). They also often bear a pasted label including a classification code (a number), which could be, as suggested by our college Jérôme Petit (curator at the Department of Manuscripts, BnF), a remnant of systematic classification of the Société Asiatique. In the hypothesis that the title pages are indeed the work of Ariel, their presence allows us to identify these manuscripts, whose provenance has not been duly recorded, notably the manuscripts under the classification code “Sanskrit” in the BnF. The papers of Ariel that were received by the BnF are divided between the classification codes “Indian” and “NAF”.

The printed books are currently kept at the Asiatic Society. They can be identified by their stamp “Société Asiatique Don Collection Ariel” (Drouin E., 1892, p. 369). Rather than a stamp, others bear the handwritten signature of Ariel. Of the Tamil books that we have been able to consult, many bear the transcription/translation of the title page by Ariel. A more thorough examination of the collections of the Asiatic Society would allow a more precise determination of the number of books in his donation.

The artifacts were put on sale by the Asiatic Society, except for the coins and two marble Buddhas, which the society kept to decorate the meeting hall (Drouin E., 1892, p. 369; Finot L., 1922, p. 59). The Bhuddas are probably stillin the meeting hall, and the coins have been inventoried (Drouin E., 1892, p. 369-370).

The Tamil manuscripts of Ariel are an exceptional resource. Ariel was a connoisseur of Tamil literature and carefully selected the manuscripts that he acquired. He was careful to obtain as many examples of the most important works as possible. Furthermore, Ariel was able to acquire ancient manuscripts dating to the 18th century, likely due to the linguistic skills that helped him procure his post. Ariel’s Tamil manuscripts are among the oldest preserved today. Their counterparts in India are not preserved in climatic conditions as ideal as those of Paris. Ariel’s collection of printed material in Tamil is also notable since it containins rare examples of books printed in Madras in the first half of the 19th century, when the printing press first began to use Tamil characters.

Until now, Ariel’s papers have only offered a few clues about how Ariel managed to put together his collection of manuscripts. A few lists of works, however, provide helpful information (BnF, Indien 164, f. 239-241). One (f. 239) gives a series of works from the hand of a certain B. Gnanappragassen (Tamoul Nanappirakacan) that indicates the price corresponding to a grandam (line of copied text). It thus seems to be an estimate for copies requested by Ariel via an Indian intermediary. This last note (in French): “The copyists request one rupee for 1,000 grandams. I will manage to reduce something.” We note that Ariel had obtained a substantial bonus (1,500 rupees = 3,500 Francs) from the administration of Pondicherry (BnF, Indien 1061, f. 10ro). It is likely that he put this capital to use, along with his wages as a civil servant, to acquire ancient manuscripts and commission copies from professional copyists.

Related articles

Collection / collection d'une personne

Personne / personne