BEAUJON Nicolas (EN)

Nicolas Beaujon Merchant: 1740-1753

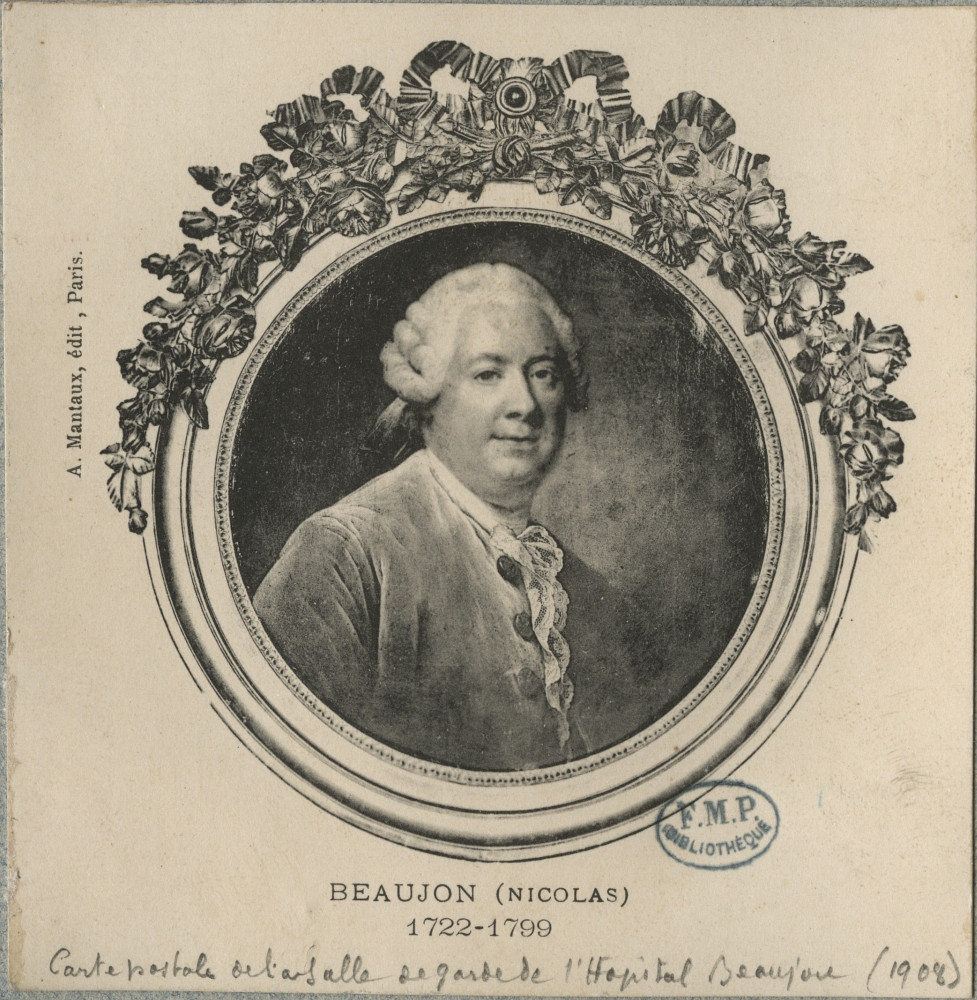

Nicolas Beaujon was born in the parish of Saint-Pierre on February 28, 1718 (AM Bordeaux, Registre des mariages et sépultures de Saint-André (1706-1713),no 1981). He was the son of Jean Beaujon (16901745), an affluent dealer of grain and wine in the city of Bordeaux, and of Thérèse Delmestre (1687-1730), a young woman from the rich bourgeoisie of the parish of Saint-Pierre. From his earliest years, Beaujon was associated with his father’s commercial affairs. In 1740, he was sent to Brittany, at the instigation of the bursar of Bordeaux, Aubert de Tourny (1695-1760), to handle the purchase of grain to supply Limousin. In 1743, when Guyenne was struck by famine, Tourny again called upon Beaujon, as well as in 1747 and 1748. After Jean Beaujon died in 1745, his son Nicolas took over the business and additionally created a trading company with farmer general Étienne Michel Bouret (1710-1777). This enterprise would bring them profits of nearly 200,000 pounds. Impressed by Beaujon’s assiduousness, the Bordeaux chamber of commerce elected Beaujon as Director of Commerce of Guyenne in 1748 (Masson A., 1937, p. 17-34).

After procuring provisions for Guyenne, Nicolas Beaujon again proved his commitment to the government by ensuring armaments for Canada for the account of the king (Communay A., 1888, p. 70), and in delivering munitions to Quebec after the seizure of Louisbourg during the War of the Austrian Succession. He also furnished arms to the Antilles and to Canada.

Nicolas Beaujon Financier: 1753-1774

After establishing himself as a merchant-trader in Bordeaux, Nicolas Beaujon expanded his influence by leaving this city for Paris as of 1753. In 1825, Ludovic Lalanne wrote in his Dictionnaire historique de la France (Labat G., 1902, p. 1-6): “Persecuted by the Parliament in regards to an operation on wheat, he took refuge in Paris, where the government made him responsible for various financial affairs which would soon gain him an immense fortune, which would put to very noble use.” Larousse also explains: “Foreseeing famine, he purchased and placed in reserve a great quantity of wheat; the following winter, famine reigned across the generality of Bordeaux and Beaujon ably speculated on the inhabitants’ needs. Frightened by the rumours and above all by the beginning of judicial action by the Parliament, he left his city of birth and came to Paris, where he could not only bury this unfortunate affair with the aid of his relationships, but also give free rein to his remarkable financial talents (Labat G., 1902, p. 1-6).” We see by these commentaries that opinions converged to conclude that the financier had speculated on grains, and that he voluntarily sought refuge in Paris to hush up the affair of the supplies for Guyenne.

In any case, after his departure from Bordeaux, Beaujon established himself in Paris and solidified his professional and social success with a brilliant marriage in 1753 to Louise-Élisabeth Bontemps (deceased 1769) [AN, T/306], the daughter of the first valet to Louis XV, Louis Bontemps (16691742), niece of the Maréchal de Varenne, and cousin of the farmer general Ange-Laurent Lalive de Jully (1725-1779). This union allowed Beaujon to introduce himself into the world of the Court and of Parisian finance. Upon Louis Bontemps’s death in 1747, Louis XV granted his son the succession of his former position of first valet, and to his widow the right to continue living in the first valet’s apartment in the Tuileries. Consequently, when Beaujon married Louise-Élisabeth Bontemps in 1753, he initially moved into the family apartment in the Tuileries, before finding lodgings in the rue du Dauphin (Masson A., 1937, p. 36). The year of Beaujon’s marriage thus witnessed the exaltation of the former merchant, through his alliance with a family intimate with the king and his installation in the Tuileries.This alliance allowed him to rub shoulders with the most elevated personalities in the kingdom. This is attested by Beaujon’s marriage contract, which bears the signatures of Louis XV, Marie Leczinska (1703-1768), and Madame de Pompadour (1721-1764), as well as the ministers Machault d'Arnouville (17011794), Saint Florentin (1705-1777), D’Argenson (16941757), Rouillé (16891761) and Gratien Drouilhet (1702-1756), receiver-general of finance of La Rochelle (AN, V1/506).

Upon Drouilhet’s death three years later in 1756, Beaujon made his entrance into the world of Parisian finance by purchasing the position of receiver-general of finance of the generality of La Rochelle on even-numbered years. Receivers-general of finance were responsible for collecting direct taxes such as la taille, le vingtième and la capitation in the 24 generalities of the kingdom. At two per generality, the receivers-general alternated in their assumption of responsibilities, one taking even years, the other odd. The government, endlessly short of money, had become accustomed to requesting advances on future collections from financiers, which explains why certain financiers also became bankers.

In 1766, Beaujon became secretary advisor to the king, house and crown of France and its finances (AN, V²/49, folio 427428), and in 1769 he received the certificate of state counsellor (AN, O1/114, f. 1057). In 1771, he also became general treasurer of the royal and military order of Saint-Louis (AN, MC/ LV/76).

In addition to these responsibilities, the principal activity of the financier as banker of the court consisted of procuring the money needed by the government for the royal treasury.

Nicolas Beaujon and his Circle

Once in Paris, Nicolas Beaujon presumably developed contacts with individuals that he had already had the occasion to frequent when still a merchant in Bordeaux, such as the Minister Jean-Baptiste de Machault d'Arnouville (1701-1794) and other ministers of the king. On Beaujon’s marriage contract (AN, T/306), we drew attention to the signatures of Saint-Florentin, d'Argenson, Rouillé or AngeLaurent Lalive de Jully, which indicate links between Beaujon and the minsters of the court.

Through his association with a family close to the king, Nicolas Beaujon also widened his circle by frequenting the kingdom’s highest personalities who had been present at his marriage. Thus, Louis XV, the brother of the king, Marie Leczinska, and Madame de Pompadour can be counted as another part of the financier’s circle. Furthemore, the lodgings that occupied by Beaujon at the time of his marriage in 1753 allowed him to establish contacts with artists such as Giovanni Niccolò Servandoni (1695-1766), the architect of Saint-Sulpice, or with the painters of the Académie royale, notably Jean-Baptiste Oudry (1686-1755)who had his studio at the Tuileries. These artists were not properly part of Beaujon’s circle, but they may have brought him in closer contact with the artistic milieu. We know, from the catalogue of Nicolas Beaujon’s sale from April 25, 1787 (BINHA, MF/25/1787), as well as from the catalogues of sales where the financier himself made purchases (Blondel de Gagny [1695-1776] in 1776, Randon de Boisset [1708-1776] in 1777, the prince of Conti [17171776] in 1777, the marquis de Ménars [1727-1781] in 1782) (BINHA, MF/25/1776; MF/25/1777, MF/25/1782), that the dealers Pierre Rémy (1715-1797) and Jean-Baptiste-Pierre Le Brun (1748-1813) sought paintings for Beaujon.

The collection

Following his move to the Hôtel d’Évreux in 1774 (AN, MC/LIII/500), Nicolas Beaujon began focussing on auctions in order to build a collection of paintings, sculptures, and artefacts. The financier’s sales catalogue, dated April 25, 1787 (BINHA, MF/25/1787), was written by Pierre Rémy and Claude-François Julliot (1727-1794). Each work is described precisely and in some cases the provenance is emphasised. Beaujon acquired some works through the sales of Blondel de Gagny (1776), Randon de Boisset (1777), the Prince of Conti (1777), and the Marquis de Ménars (1782). The majority of his paintings come from these sales, while other, less prestigious works came from the sales of Julienne (1767), La Guiche (1771), Du Barry (1774), Lempereur (1775) and Le Rebourg (1778). It may be supposed that Beaujon himself sometimes went to the salesrooms to make the bids, and that at other times he authorised an agent to oversee the purchases. In analysing the catalogues from sales where Beaujon made purchases, it is not always obvious whether he was in attendance or had sent someone in his place. In the sale catalogue of Blondel de Gagny (BINHA, MF/25/1776), we read that the dealer Pierre Rémy bought for him two large vases of blue and gold. This is the only example where it is specified, in the catalogue margins, that a dealer was representing Beaujon in his name (“Rémy pour M. de Beaujon”). Outside the public auctions, Beaujon was able to place direct orders with dealers or artists, or to make exchanges. The archival documents, such as an inventory of the financier’s papers (AN, MC/LV/76.), do not however allow us to draw any conclusions regarding a typical method of acquisition.

Composition of the Collection in 1786

Nicolas Beaujon’s collection of paintings consisted primarily of the Italian, Flemish, and French schools. The Italian school was well-represented by primarily religious scenes.

The painters Guido Reni (1575-1642), Paolo Véronèse (1528-1588), Carlo Maratta (1625-1713), Luca Giordano (1634-1705), Giovanni Paolo Pannini (1691-1765) and Benedetto Castiglione (1609-1664) were present in the financier’s office. The paintings of the Flemish and Dutch schools were more numerous than the Italian schools. Landscapes, seascapes, portraits, and genre scenes were better represented than religious subjects (66 against 5). Rubens (1577-1640), Paul Bril (1554-1626), Cornelis van Poelenburg (1594-1667), Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669) and David Teniers le Jeune (1610-1649) were among the financier’s favourites. To these names we can add Adriaen van Ostade (1610-1685), Bartholomé Breenbergh (1610-1660), Jan Both (1618-1652), Nicolaes Berghem (1620-1683), and Gabriel Metsu (1629-1667), with his famous Femme au clavecin avec son maître (Paris, musée du Louvre, inv. 1462), and Frans van Mieris (1635-1681) with his Femme écrivant sur un tapis de velours (Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv. A261). The French school was also well represented. Among the painters appreciated by the banker were Nicolas Poussin (1594-1665), notably with Achille parmi les filles de Lycomède (Boston, Museum of Fine Arts, inv. 46.463), Carle van Loo (1705-1765), Joseph Vernet (1714-1789), Jean Baptiste Greuze (1725-1805), François Boucher (1703-1770) with Vénus dans les forges de Vulcain (Paris, musée du Louvre, inv. 2707), and finally Jean Baptiste Marie Pierre (1713-1789) with a version of L’Enlèvement d'Europe. The banker also owned several seascapes of the English school, paintings in gouache and in enamel, pastels, and reverse glass paintings.

Beaujon’s sculpture collection was less voluminous, but nonetheless included fine marbles by 18th century artists, including Étienne Falconet (1716-1791), Augustin Pajou (1730-1809), Laurent Guyard (1723-1788), Pierre Ignace Joseph Barbieux (active mid-18th century), René Frémin (1672-1744), Philippe Bertrand (1663-1724), Louis Claude Vassé (1716-1772) and Jean Pierre Antoine Tassaert (1727-1788). The majority of these sculptures were in marble, but we also encounter bronze, talc, and stucco. It is interesting to note that Beaujon possessed less statues in bronze (35 sculptures in marble versus 15 in bronze), although at the time the taste for bronzes was burgeoning.

The Beaujon collection was also made up of artefacts such as vases in porphyry, granite, touchstone and alabaster. Some of these pieces come from the sales of Blondel de Gagny, the Prince de Conti and Randon de Boisset. Here can be noted a not inconsequential quantity of porcelains from Asia (vases, urns, bowls, and bottles in celadon from Japon and China, in blue Turkish porcelain, in celestial blue porcelain, in jaspé porcelain, in coloured porcelain from China, and in porcelain of Saxony). We find with other collectors of the period, notably those of bankers conscious of conforming with the general trends (Pierre-Paul-Louis Randon de Boisset [1708-1776] and Augustin Blondel de Gagny (1695-1776) among others), this same taste for porcelain of the Far East. The preference of collectors of the second half of the 18th century went to the porcelain of Japan, dubbed “ancient Japan”, “ancient Japanese white”, “ancient Japanese coloured porcelain”, “ancient coloured Japan of the first class”, or “first coloured quality”, which for the delicateness of its paste prevailed over that of China (“ancient coloured China”, “ancient coloured porcelain of China”) [Castelluccio S., 2013, p. 150-151]. The more light and delicate decor of the Japanese pieces was a choice criterion.

The catalogue from the sale of Nicolas Beaujon’s collection (BINHA, MF/25/1787) does not mention provenances, expecting one piece of celestial blue porcelain representing a ribbed oval shell with snails in relief and two large Lisbet vases in dark blue and gold, both from the sale of Blondel de Gagny. One can nonetheless suppose that the financier procured pieces from the marchands-merciers. In Paris, the majority of luxury commerce was concentrated in the area around les Halles (quai de la Mégisserie, rue Saint-Denis and rue Saint-Honoré). Here, both ceramists and merchants sold such porcelains, although the latter, more attractive due to the audacity of their creations (mounting of oriental porcelain on gilded bronze), better captured the attention of connoisseurs (Castelluccio S., 2013, p. 315). Initially designed to complement the porcelain’s shape, the mountings in gilded bronze gradually freed themselves from the object to develop freely on their own. The apparition of new motifs in shells, the decisive role of ornamental designers such as Juste Aurèle Meissonnier (1695-1750) or Nicolas Pineau (1684-1754), and the creative spirit of the marchands-merciers together encouraged the growing taste for porcelain.

Finally, the Beaujon collection included objects of furniture such as standing clocks, dresser drawers, secretaries, desks, and armoires. There is mention of a large lacquered armoire (BINHA, MF/25/1787). It may seem surprising that a collector of Asiatic art objects had so few lacquerware objets, but Beaujon was first and foremost a businessman withvarious professional responsibilities. He thus left it to the marchands-merciers to build him a collection at the level of his social and professional stature. Beaujon also possessed a variety of tapestries woven at les Gobelins that represented portraits of the royal family and important personnages of the kingdom. Upon the financier’s death these tapestries were donated to the Chamber of Commerce of Bordeaux, where they are persevered today (AD de la Gironde, C/4258).

Visibility of the Collection in Public and Private Spaces

When Nicolas Beaujon began to collect, he owned the Hôtel d'Évreux, a veritable showcase for displaying his collection (AN, MC / LV / 76 and Thiery, L.-V., 1787, p. 8288). The entrance vestibule was decorated with four marble busts by Philippe Bertrand representing the seasons, while the billiard room contained L’Amour et Psyché by Tassaert. In the small living room stood an urn-shaped clock and a white marble table, as well as two gilt bronze mounted vases from Japan. These spaces were mainly embellished with antique style sculptures, as well as vases and porcelain.

Most of Beaujon’s paintings were arranged in the small apartments of the Hôtel d'Évreux. The footmen’s anteroom contained Saint Roch by Guido Reni and Sénèque au bain by Guercino (1591-1666). The living room contained, in addition to a turquoise-blue marble table, paintings by Pater (1695-1736), Lancret (1690-1743), Van Loo, Houël (17351813) and Doyen (17261806). In the study were more solemn paintings, namely four portraits of Louis XVI, portraits of the count of Provence, the count of Artois and the King of Sweden, Gustave III. The walls of the so-called "green" living room were decorated with four tapestry portraits from the Gobelins: of Louis XV, after Louis-Michel van Loo (1707-1771); of Marie Leczinska, after Jean-Marc Nattier (1685-1766); of the future Louis XVI dauphin, after Louis-Michel van Loo; and of the dauphine Marie Antoinette, after François-Hubert Drouais (1727-1775), as well as two tapestries representing La Pêche and La Diseuse de bonne aventure, after Boucher. The gallery of paintings, created by the architect Étienne-Louis Boullée (1728-1799), was accessed through the living room of the small apartments.

This room, longer than wide according to the usual definition of the gallery, had overhead lighting. The perimeter of the walls was fitted with low cabinets forming a base and enclosing the Beaujon library, created by Hémery. On the marble tables were placed vases in bronze, porcelain and marble. On the walls of the gallery hung the works of Jean-Baptiste Santerre (1651-1717), Pierre Paul Rubens, Frans van Mieris, Charles Le Brun (1619-1690), Nicolas Poussin, Louis Michel van Loo, David Teniers the Younger, Paul Bril, Hans Rottenhammer (1564-1625), and Francesco Zuccarelli (1702-1788), as well as Philips Wouverman (1619-1668), Joseph Vernet and Gabriel Metsu. We do not know the exact arrangement of these paintings, but the decision to place the gallery on the edge of his small apartments shows that Beaujon wanted to place his collection as close as possible to his private quarters. At la Chartreuse, most of the paintings appeared in the living room, as well as his works in gouache, enamel paintings, pastel, and reverse glass, as well as miniature paintings. (AN, MC / LV / 76).

Through these different methods of presentation, it is clear that Beaujon wanted to separate the private spaces (small apartments at the Hôtel d'Évreux, la Chartreuse) from the public spaces (large apartments at the Hôtel d'Évreux). Its gallery of paintings mainly showed works from the Italian and “Flemish” schools of the 17th and 18th centuries. The other rooms in the small apartments of the Hôtel d'Évreux presented either paintings from a specific school or along a particular pictorial theme: thus, in the living room of the small apartments, the paintings were all from the French school of the 18th century, whereas in the study and the green living room hung the paintings of princes and sovereigns, as well as the tapestries from les Gobelins.

Related articles

Collection / collection d'une personne

Personne / personne