GOLOUBEW Victor (EN)

Education (1878-1904)

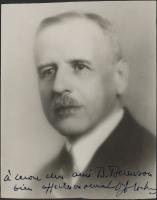

The life of Victor Victorovitch Goloubew (February 12, 1878 – April 19, 1945) is well-documented in obituaries written by Louis Malleret (1901-1970) (Malleret L., 1964, 1967). He was the second son of the state councillor and engineer Victor Fedorovitch Goloubew (1842-1903) and his wife Anna Petrovna, née Lossef, and he belonged to a wealthy family of the Russian aristocracy. Victor Goloubew's education placed a great emphasis on foreign languages and the arts. He learned French, English, German, Italian and became an excellent violinist.

Victor Goloubew began his higher education in Russia. He spent four years (1896-1900) at the Faculty of Sciences of the University of Saint Petersburg (Malleret L., 1967, p. 332), before leaving his native country with his wife Nathalie Cross (c. 1882- 1941), whom married in Kiev in 1900, to study at the University of Heidelberg. Between 1901 and 1904, he wrote a philological thesis on the works of Marivaux – Marivaux' Lustspiele in deutschen Übersetzungen des 18. Jahrhunderts – which was accompanied by a specialisation in art history and archeology. His eldest son, Victor (1901- n.d.), was born in Germany during the couple's first year of residence.

Stay in Paris (1905-1920)

Once he completed his education, Victor Goloubew moved to Paris in 1905 (Malleret L., 1967, p. 333). His second child, Ivan (1905-n.d.), was born in France the same year. His wealth from his land in Ukraine and his stock market shares – Victor Goloubew was notably a member of the board of directors of Lena Goldfields Limited, an English gold mining company in Russia (Annuaire Desfossés, 1910, p. 415) – allowed him to live from dividends until the advent of the First World War. Upon his arrival in the French capital, he moved into a luxurious apartment on what is now Avenue Foch (Malleret L., 1964, p. 437) and devoted the following decade to enriching his collection as well as to various activities related to the history of art, including teaching. In particular, he conducted research that led to the publication of a two-volume study of the sketchbooks of Jacopo Bellini (1400-1470) [Goloubew V., 1908 and 1912].

Around 1907, Victor Goloubew began to show a growing interest in the Orient. In 1907-1908 he made several trips (EFEO, fonds Victor Goloubew, D-1, 60, notice individuelle), first to Turkey, then to Egypt and Sudan where he journeyed along the Nile accompanied by his friend, the writer Charles Muller (1877-1914). At the same time, he wrote his first article relating to Asia: "Les races mongoles dans la peinture du Trecento", which appeared in 1907 in the Bulletin de la Société des antiquaires. He joined the Société Asiatique the following year. The year 1908 also marked the separation of the Goloubew couple, as Nathalie had become the mistress of the poet Gabriele d'Annunzio (1863-1938) [Malleret L., 1967, p. 334-336]. However, Victor Goloubew, having already given his wife a million francs at her departure (Berenson, Stewart Gardner and Van N. Hadley, 1987, p. 475), continued to pay monthly alimony until his death in 1941. In 1910, he reunited with Charles Müller for a six-month tour through India and Sri Lanka (Malleret L., 1967, p. 336-337). Upon his return, he gave a course on Indian art at the École des langues orientales vivantes. He was responsible for lectures and examinations within the establishment from 1912 to 1914 and from 1919 to 1920 (EFEO, fonds Victor Goloubew, D-1, 60, titres scientifiques).

Very sociable and worldly, Victor Goloubew developed an important network of relationships in the artistic and political spheres in Germany and then France. The publisher Gérard Van Oest (1875-1935), whom he met in 1905 and with whom he had already collaborated to publish his work on Jacopo Bellini, enabled him to realise a project conceived during his trip to India: the creation of a collection entitled Ars Asiatica, under his direction, whose first volume, La Peinture chinoise au musée Cernuschi. April-June 1912, appeared in 1914. Auguste Rodin (1840-1917) was also among the Goloubew couple's acquaintances: he produced a bust of Nathalie in 1906, a marble version of which is in the Pola Museum of Art in Hakone (Japan) and a bronze in the Musée Rodin in Paris (S.01037) [Kessler H., 2017, entrée du 29 mai 1905, note no 1). Rodin, who shared Victor Goloubew's interest in Indian art, agreed to collaborate on the third volume of Ars Asiatica. It appeared in 1921 under the title Sculptures çivaïtes. Goloubew also had friendly ties with René-Jean (1879-1951), the librarian of fashion designer and collector Jacques Doucet (1853-1929). He contributed to his library of art and archeology by donating books.

At the outbreak of the First World War, Victor Goloubew – who was not naturalised in France until 1926 (Journal officiel, 1926, p. 10226) – was exempt from military obligation in his country of residence. However, he chose to participate in the conflict and until 1916 directed the ambulance service made available to the French government by Russia (Malleret L., 1967, p. 338-340). He served the rest of the war as a soldier in the Russian infantry brigade sent by the Tsar. In 1917, the Russian Revolution put an end to his prosperous existence. Ruined, Victor Goloubew was forced to part with his valuables. He had to leave his luxurious apartment to move into rue Théodore-de-Banville, sell his Stradivarius and get rid of his works of art. Thanks to these sales, he “still lived for some time with the remains of his fortune” (Malleret L., 1967, p. 341) before finding a job as an orientalist thanks to “friends who introduced him to Louis Finot [1864-1935]” (Malleret L., 1967, p. 341), the director of the École française d’Extrême-Orient.

Member of the École française d’Extrême-Orient (1920-1945)

By decree of August 4, 1920 Victor Goloubew obtained the title of temporary member of the École française d’Extrême-Orient (Malleret L., 1964, p. 437), whose headquarters were then in Hanoi, Tonkin. He left for French Indochina at the end of the year. After landing in Saigon, he spent a few months in Cambodia, then returned to Hanoi in June 1921 (Malleret L., 1967, p. 342). He would maintain his main residence in this city until his death.

The twenty-five years that Victor Goloubew spent in the service of the school were rich in publications and scientific missions in Asia and Europe. Throughout his career, he gave numerous lectures on subjects related to the art of Southeast Asia. His interpersonal skills and mastery of several languages made him a natural choice for representing his institution abroad. He attended international scientific congresses on several occasions and made presentations in European institutes to publicise the school’s work (BEFEO, 1929, p. 466; BEFEO, 1934, pp. 772-792; BEFEO, 1938, p. 453; BEFEO, 1939, p. 350; EFEO Archives EFEO, fonds Victor Goloubew, C-1, dossiers 27, 35 & 39). In France, he contributed to the organisation of the colonial exhibitions of Marseille (1922) and Paris (1931), during which the École française d’Extrême-Orient presented its activities to the cities’ inhabitants (BEFEO, 1923, p. 503-569 ; Archives EFEO, fonds Victor Goloubew, C-1, dossiers 22 & 45).

In Indochina, he participated in excavations in Vietnam (BEFEO, 1923, p. 505) and Cambodia and played a pioneering role in the use of aerial reconnaissance to identify archaeological remains. Victor Goloubew also took part in the excavations of Angkor, where he carried out campaigns on several occasions (BEFEO, 1933, p. 1046-1047; BEFEO, 1936, p. 619 -623; BEFEO, 1937, pp. 651-656). His observations led him to formulate a hypothesis concerning the footprint of the oldest town on the site. According to him, it took the form of a quadrilateral centred on the hill of Phnom Bakheng. An article from 2000 (Pottier C., 2000) analyses in detail the hypothesis put forward by Victor Goloubew. Its author demonstrates that it "very significantly participated in propagating the image of the Angkorian city, rigorously designed, surrounded by a square enclosure, thus reinforcing the idea of a delimited and centred geometric model [...]" (Pottier C., 2000, p. 79) and uses new analyses to prove that it must have been abandoned. Although Goloubew's theory of city limits ultimately proved wrong, its resonance at the time earned him the Giles Prize in 1935 (BEFEO, 1935, p. 497).

Released from his military obligations because of his age, Victor Goloubew spent the Second World War in Hanoi, where he held the position of deputy general delegate of the French Red Cross for Indochina (Archives EFEO, fonds Victor Goloubew, carton C-1, dossier 1). In 1941, he carried out his last mission for the School in Japan. On April 19, 1945, he died of heart disease at the Saint-Paul clinic in Hanoi.

First Purchases: French Paintings

Victor Goloubew's collection reflects his curiosity and eclectic tastes; the evolution of his centres of interest led him from French painting to Persian miniatures and finally to Chinese statuary.

His background undoubtedly played a decisive role in the creation of this ensemble. Beyond the financial ease necessary for the acquisition of works, his family circle also gave him a taste for art: his father, Victor Fedorovitch, himself owned a collection of European paintings. Known from an 1897 insurance inventory detailed by Marina Polevaya (2008, p. 316-317), this included paintings by artists such as Canaletto (1697-1768), Charles-Antoine Coypel (1694- 1752), Bartolomé Esteban Murillo (1618-1682), Peter Rubens (1577-1640), Diego Velazquez (1599-1660) and Anton Raphael Mengs (1728-1779). When his father died in 1903, Victor Goloubew inherited some works. He notably received a watercolour by Paul Gavarni (1804-1866) entitled L’Indienne, as well as Le Cloître, a painting by François Marius Granet (1775-1849). These works, which appear in the inventory of Victor Fedorovitch (Polevaya M., 2008, p. 316-317), are listed as the property of his son on the occasion of the French art exhibitions to which he lent them in 1912 and 1914 (Exposition centenniale de l’art français à Saint-Pétersbourg. 1812-1912 and Exposition d’art français du xixe siècle in Copenhagen). Although their titles have changed, the paintings remain identifiable due to their subjects.

Victor Goloubew owned several canvases by Paul Gauguin (1848-1903), probably acquired while he was still a student in Heidelberg thanks to the indirect action of Count Harry Kessler (1868-1937). A 2005 article (Joyeux-Prunel B.) highlights Kessler's role as intermediary between German collectors and Ambroise Vollard (1868-1939), the painter's dealer. “Kessler was able […] to bring to Vollard his friend Baron Eberhard von Bodenhausen […]. Through the latter, the merchant had access to the Baron and Baroness de Golubeff of Wiesbaden” (Joyeux-Prunel B., 2005, p. 134). Victor Goloubew and Ambroise Vollard were in contact in 1904, and the Goloubew couple frequented Kessler after he settled in Paris.

Victor Goloubew's acquisitions on the Parisian market began the year he arrived in the French capital, notably with the work Paysage à l'Étang-la-Ville by Édouard Vuillard (1868-1940), purchased from the Bernheim-Jeune gallery "on February 22, 1905, for 750 frs" (musée d’Orsay, fiche œuvre no 21255 [online]). The quality of the works he owned earned him participation as a lender in the exhibitions of French art in Saint Petersburg (1912) and Copenhagen (1914). The catalogs of these exhibitions (Exposition centennale de l’art français à Saint-Pétersbourg. 1812-1912, 1912 and Exposition d’art français du xixe siècle, 1914) list works belonging to him painted by Gauguin, Maurice Denis (1870-1943), René Piot (1866-1934), Odilon Redon (1840-1916), Jules Flandrin (1871-1947), and also Charles Daubigny (1817-1878).

Victor Goloubew was also interested in Italian art of the Quattrocento, with a particular penchant for Venetian painting. The favorable situation of Venice, a commercial crossing point between the East and the West, had led to the introduction of foreign elements into the production of the painters of the lagoon. Louis Malleret (Malleret L., 1967, p. 335) notes the interest with which Victor Goloubew tended towards these influences, through which he discovered oriental art.

The Discovery of the Orient: Miniatures of the Islamic World

The first Asian work acquired by Victor Goloubew was a Persian miniature (René-Jean, 1914, p. 10). His new passion quickly gained considerable momentum: between 1908 and 1911 its owner assembled one of the most important European collections in this domain. His trip to India was an opportunity to enrich this set; Victor Goloubew “count[ed] on [his] stay in India to complete [his] collection of Persian and Hindu miniatures” (Malleret L., 1967, p. 336). To this end, he made purchases from merchants in the north of the country: quoted by Louis Malleret (1967, p. 336), Victor Goloubew wrote: "My room [overflowed] with Korans and Chah-namehs with fine illuminations, albums of calligraphic paintings, Mughal and Rajput paintings that silent and affable merchants brought me every day by armfuls. Sometimes we went to the bazaar to some high-caste antiquarian who claimed to possess precious manuscripts. It was in Delhi that chance introduced me to a batch of Chinese paintings recently brought from Tibet. A scroll from the Ming period, particularly rich in imperial seals and skilfully traced legends, seemed to me the work of a master.”

At the same time, other Parisian amateurs, such as Georges Marteau (1851-1916) or Henri Vever (1854-1942), formed similar collections (Miniatures persanes tirées des collections de MM. Henry d’Allemagne, Claude Anet, Henri Aubry […] et exposées au Musée des Arts Décoratifs. Juin-octobre 1912 , 1913). The constitution of these large collections of miniatures from the Islamic world was favoured by the arrival of many Persian manuscripts in Paris, following Iran’s political troubles at the beginning of the 20th century (Hillenbrand R., 2010, p. 205). The collection of Victor Goloubew (Coomaraswamy A., 1929) had just under 160 paintings, bearing a certain stylistic and thematic diversity. Persian miniatures from the Safavid dynasty were in the majority, but there were also many Mughal works as well as Ottoman and Abbasid miniatures in smaller quantities. The wealth of this collection enabled him to take part in a major exhibition of Islamic art that was organised in Munich in 1910: Meisterwerke muhammedanischer Kunst, to which he loaned sixteen works (Ausstellung von Meisterwerken muhammedanischer Kunst, Musikfeste, Muster-Ausstellung von Musik-Instrumenten: amtlicher Katalog, 1910).

In 1912, he placed all of his miniatures at the Musée des Arts décoratifs, located in the Marsan pavilion (Miniatures persanes tirées des collections de MM. Henry d’Allemagne, Claude Anet, Henri Aubry […] et exposées au Musée des Arts Décoratifs. Juin-octobre 1912, 1913, p. 7). Displaying this exceptional collection offered curator Louis Metman (1862-1943) the opportunity to organise a larger event by calling upon other connoisseurs, which resulted in the exhibition Miniatures persanes, presented from June to October 1912. The works of Victor Goloubew were installed separately from the others in the exhibition’s first room. This exceptionality can probably be explained by commercial motives: the exhibition provided an excellent advertising opportunity (Zaras E., 2019, p. 78). Indeed, Victor Goloubew by then wished to get rid of his miniatures in order to turn entirely towards the art of the Far East, which he was concomitantly collecting.

From the Mideast to the Far East

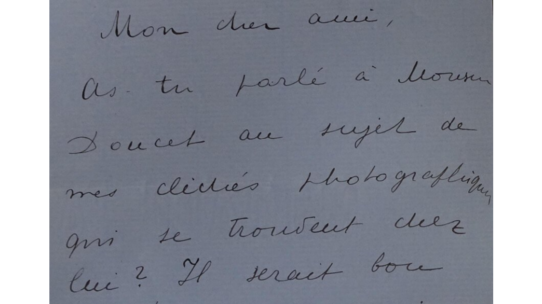

In 1914, Victor Goloubew sold all of his miniatures to the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston , through the dealer Rudolf Meyer-Riefstahl (1880-1936) (Coomaraswamy A., 1929, p. 5). Their acquisition gave rise to the publication of an exhaustive catalog by Ananda Coomaraswamy (1877-1947), in the Ars Asiatica collection in 1929 (Coomaraswamy A., Les Miniatures orientales de la collection Goloubew au Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, 1929). Although Goloubew had previously refused offers for this set of works, their sale allowed him to raise the necessary funds to finance a second trip to India, scheduled for April 1914, as well as the realisation of another project: the construction of a "villa-museum" (Ploegaerts L., 1989, p. 81) at 39, rue Cortambert, where he intended to set up his Far Eastern collections. During the First World War, he wrote to René-Jean: "I thought the other day about our Asian project, while visiting the house in rue Cortambert. Nothing could be easier than installing bookcases, card cabinets, collections […]" (Archives Inha, 191, 21 , pièce no 853) The plans - now kept at the Musée d'Orsay, inventory numbers ARO 1985 78 to ARO 1985 85 1 and ARO 1982 102 to ARO 1982 115 - were entrusted to the Belgian architect Henry van de Velde, who had already fitted out his apartment on avenue Foch, but Victor Goloubew never lived in the building, which was “put under sequestration with all German property during the conflict […]” (Ploegaerts L, 1989, p. 94), then sold.

Victor Goloubew's interest in the Far East was born of Chinese influences which he detected in Persian painting (Collection Victor Goloubew. 5th Exhibition of Asian Arts, 1913, p. IV-V). Gradually, he turned away from the arts of Islam to devote himself to those of China, Japan and the Indian subcontinent. Like his collection of miniatures, the large collection of Far Eastern and South Asian objects in his possession aroused the interest of connoisseurs. The number, diversity and quality of the pieces he owned made him a privileged lender for the exhibitions of the Musée Cernuschi. With the collaboration of its curator, Henri d'Ardenne de Tizac (1877-1932), he participated in four exhibitions between 1911 and 1914: the first, third, fourth and fifth retrospectives of Asian arts. He lent works to all and also collaborated on the catalogs of the third and fourth.

Victor Goloubew began by loaning 5 works in 1911, including a Chinese carpet, then 24 paintings in 1912, and 43 objects in 1913 (Sudre A., 1998, p. 28). The 1913-1914 exhibition, entirely devoted to his collection, brought together 157 works from various sources (Collection Victor Goloubew. 5th Exhibition of Asian Arts, 1913). China occupied the first place in the collection, with several dozen paintings, terracottas, carpets and Buddhist statues, including a stele from the Wei dynasty that represents the Buddha accompanied by two bodhisattvas and two monks. This piece, among the most remarkable of the set, was sold in 1914 to Isabella Stewart Gardner (1840-1924) through Bernard Berenson (1865-1959) (Berenson, Stewart Gardner and Van N. Hadley, 1987, p.517). It is now kept in the museum created by the collector in Boston (n° S8w4). The second most represented country is Japan, with paintings on silk and statues in lacquered and gilded wood, as well as five screens (Collection Victor Goloubew. 5e Exposition des Arts de l’Asie, 1913). Victor Goloubew also owned of Indian, Tibetan, Indonesian and Cambodian objects, but these were a minority with regard to the whole. Among them were fragments of a ceremonial chariot and a small dancing Krishna from southern India, a bust of Khmer Buddha and a statue from Gandhara (Collection Victor Goloubew. 5e Exposition des Arts de l’Asie, 1913).

Goloubew had a more limited interest in African arts; the exhibition Collection Victor Goloubew. 5e Exposition des Arts de l’Asie of 1913-1914 at the Musée Cernuschi included four Congolese ivory statuettes. He also lent a Baoulé fetish to the "Première exposition d'art nègre et d'art Océanien" organised at the Devambez gallery by Paul Guillaume (1891-1934) in May 1919 (Première exposition d'art nègre et d'art Océanien organisée par M. Paul Guillaume, 1919).

Dispersion of the Collection Goloubew

The Russian Revolution put an end to Victor Goloubew's collecting activity. Perhaps for the sake of discretion for his reputation, he did not organise a public auction. He seems to have preferred to sell to connoisseur among his acquaintance by gradually getting rid of parts of his collection. In 1919, the sale catalog of the collection of Adrienne Baddly (hôtel Drouot, 7-9 avril 1919, Collection de Mademoiselle Adrienne Baddly. Objets d’art et d’ameublement du XVIIIe siècle. [...] Miniatures persanes – Peintures chinoises & japonaises anciennes. Étoffes anciennes – Tapis d’orient & d’Extrême-Orient), which Goloubew frequented before World War I (Inha, René-Jean, Autographe 191, 21, 855), contains several dozen European or Asian works that belonged to him. Other objects were ceded to Mr. Pridonoff (nc) and resold with the rest of his collection in 1935. The preface to this sale catalog was written by Goloubew (hôtel Drouot, 11-12 décembre 1935, Catalogue des tableaux modernes, aquarelles, pastels, dessins, par Berton, Besnard […]. Objets d’art d’Extrême-Orient, céramiques de la Chine et du Japon […] provenant de la collection d’un amateur).

Most of the works from the former Victor Goloubew collection are probably on the art market today. Some reappear periodically, such as a Nature morte aux fruits et piments by Paul Gauguin, which was sold at Christie's New York on November 6, 2007, a Chinese carpet (same auction house, March 16, 2017) or a Persian manuscript (Christie's London, October 24, 2007). 2019). Others have joined public collections. They sometimes entered it during Victor Goloubew's lifetime, like the stele sold to Isabella Stewart Gardner, the miniatures from the Boston museum (Paull, FV, 1915) or even a group of three terracotta statuettes, given to the Cernuschi museum in 1914 (Bulletin municipal officiel de la Ville de Paris. XXXIIIe année, no 43, 13 février 1914. No M.C. 5601 à M.C. 5603). Conversely, some have entered museums after passing through the hands of other collectors, such as a statue of Mahakasyapa (Cleveland Museum of Art, no. 1972.166) or the miniatures numbered 1986.142.1 and S1986.142.2., at the Sackler Gallery in Washington.

Related articles

Collection / collection d'une personne

Personne / personne