KOECHLIN Raymond (EN)

Biographical article

Raymond Kœchlin was a major collector of European and Asian art, an art historian, and a committed supporter of museums. He was born in 1860 in Mulhouse, to one of the city’s oldest Protestant families, which had made a fortune in the textile industry. The members of his family were very involved in local public, economic, and cultural life, in particular through their link with the Société Industrielle de Mulhouse. His father, Alfred Kœchlin-Schwartz (1829–1895), was a municipal councillor in Mulhouse, and subsequently mayor of the eighth arrondissement of Paris (Vaugenot-Deichtmann, M., 2011, pp. 30–33). In 1888, he was elected deputy in Northern France, alongside General Boulanger. Raymond Kœchlin’s father, his sister, Florence Mezzara (1857–1896), and his brother, General Jean-Léonard Kœchlin (1870–1951), all produced artistic works, which are held in various public institutions.

During the Franco-Prussian War, Raymond Kœchlin continued his education in Paris. The Kœchlins had been Francophiles for several generations. His father opposed Prussia’s annexation of Alsace. He was forced to leave the region after the war (Vaugenot-Deichtmann, M., 2011, pp. 30–33. AN, P/LH/1405/20). In 1881, Raymond Kœchlin joined the École Libre des Sciences Politiques. He was then hired by the Journal des Débats, where for fifteen years he directed the Bulletin de Politique Étrangère. In 1887, he became a lecturer of European diplomatic history at the École Libre des Sciences Politiques.

In December 1888, Kœchlin married the painter Hélène Bouwens van der Boijen (1862–1893), daughter of the Dutch architect William Bouwens van der Boijen, who, in particular, constructed the Hôtel Cernuschi. She died five years later. Upon the death of his father in 1895, Raymond Kœchlin’s financial status evolved, and he devoted himself entirely to the study of the arts and his collection. In 1897–1898, he travelled in Egypt with the collector and art criticMarcel Guérin (1873–1948) (Guérin, M., 1932a,p. 4, p. 77). During his life, he also visited the Maghreb, Jerusalem, Palestine, Turkey, Greece, and Scandinavia. He regularly travelled to England, Germany, the Netherlands, and Switzerland. Kœchlin was a central figure in the circle of Parisian collectors.His friends included artists, curators, archaeologists, scholars, and collectors. The painter and collector Étienne Moreau-Nélaton (1859–1927) executed his portrait in 1887 (Musée d’Orsay, RF 35724). Kœchlin met Claude Monet (1840–1926) in 1897. He visited him in Giverny, defended his work, and acquired some of his paintings (Aitken, G., Delafond, M., 1987, p. 24). He was a close friend of Curator of the Louvre Gaston Migeon (1861–1930), the leading collector Jules Maciet (1846–1911), Paul Poujaud (1856–1936), a lawyer and great art lover, and Paul-André Lemoisne (1875–1964), Curator in the Cabinet des Estampes in the Bibliothèque Nationale. Another close friend, Louis Metman (1862–1943), Curator of the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris, confidedafter Kœchlin’s death: ‘(…) I have never done anything here without his agreement. Each day, until the last months of his life, he spent at least one hour in this armchair’ (Betz, M., 1931, p. 1036).

‘The devoted friend of French museums’ (René-Jean, 1932, p. 3).

His commitment to French museums was such that, according to Guérin, when Kœchlin acquired an object, he ‘never considered selling it and he only bought items with the aim of enriching the museums his collections were intended for’ (Guérin, M., 1932a,p. 13). In 1897, he was one of the founding members of the Société des Amis du Louvre, of which he was appointed Secretary General (Alfassa, P., 1932, p. 6). In 1899, he joined the board of the Union Centrale des Arts Décoratifs. In 1900, he was on the committee of the Exposition Rétrospective de l’Art Français in the Exposition Universelle held in Paris, where he helped to organise the Pavillon des Arts Décoratifs Français. The Japanese section of the Exposition Universelle, for which Hayashi Tadamasa 林 忠正 (1853–1906) was curator, had a particular impact on Kœchlin (Kœchlin, R., 1930a, p. 45–46). During this period he encouraged the museums to embrace Far-Eastern and Islamic arts and increased his donations.

Kœchlin contributed to the refurbishment of the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in the Pavillon de Marsan in the Palais du Louvre (Kœchlin, R., Metman L., 1900, p. 2.; Alfassa, P., 1932, p. 13). Two rooms were devoted to the collections of Muslim and Far-Eastern arts. In the same museum, he helped Gaston Migeon, Max van Berchem (1863–1921), and Clément Huart (1854–1926) to hold the 1903 exhibition of Muslim art, which was a decisive event for the circle of collectors of Muslim art. From 1909 to 1914, he organised, together with Louis Metman, Inada Hogitaro 稲田賀太郎, and Charles Vignier (1863–1934) a cycle of six exhibitions of Japanese prints. Thanks to loans from sixty-six collectors, 2,300 works were exhibited, providing a vast panorama of these works (Luraghi, S. D., 2014). In 1904, he took part in the committee to organise the paintings and drawings section in the exhibition of French primitive artists in the Musée du Louvre and the Bibliothèque Nationale (Bouchot et al. , 1904). In 1911, with Paul Alfassa (1876–1849), he organised the Pavillon des Arts Décoratifs Français in the Turin International Exhibition. In 1910, Kœchlin took over from Jules Maciet as Vice-President of the board of the Union Centrale des Arts Décoratifs. Upon the death of the latter in 1911, Kœchlin was appointed President of the Société des Amis du Louvre. Hence, he sat on the French Artistic Council for National Museums, of which he became Secretary in 1917 (Alfassa, P., 1932, p. 14; Vaugenot-Deichtmann, M., 2011, p. 101), and backed the creation of the Musée Rodin (L’Art et les Artistes, 1914, pp. 41–44).

Kœchlin was greatly affected by the horrors of the First World War and the subsequent destruction. He became involved with the Union des Femmes de France, founded by his mother Emma Kœchlin-Schwartz (1838–1911). He regretted having to give up certain of his epistolary exchanges, in particular those he had maintained with German scientists (Alfassa, P., 1932, pp. 14–15). He was delighted at the end of the war when Alsace-Lorraine was restored to France. In 1918, he drafted a report about the museums in these regions (BMAD, AUCAD, Br. 4422). In 1920, he was delegated by France to Vienna in the framework of the Inter-Allied Commission on Reparations (1919–1931). Raymond Kœchlin was entrusted with drawing up an inventory and estimating the value of the Austrian Crown’s collections (Gay, V., 2014, pp. 5–7). In 1921, he was elected a member of the Commission des Monuments Historiques. Hence, in 1926, he was part of a delegation responsible for examining the state of classified monuments in Alsace-Lorraine (Procès-verbaux de la Commission des Monuments Historiques (1848–1950)..., 2014). In 1922, he was elected Vice-President, then, upon the death of Léon Bonnat (1833–1922), President of the Conseil des Musées Nationaux (Callu, A., 1994). Amongst his many functions, he was one of the Vice-Presidents of the Société des Amis du Musée Guimet, established in 1926, and member of the museum’s Comité-Conseil. (Le Musée Guimet (1918-1927), Annales du Musée Guimet, 1928, p. 99).

His work as an art historian

At the same time, Kœchlin never stopped his research and publication work. He maintained written correspondence with many historians, palaeographers, and curators, such as the Director of the Victoria & Albert Museum, Arthur L. B. Ashton (1897–1983), and Laurence Binyon (1869–1943), curator at the British Museum. Kœchlin sat on the committees of the Gazette des Beaux-Arts (Comoedia, 1923, p. 3) and the Revue des Arts Asiatiques. He left his mark on research into medieval arts and Gothic ivory objects, mainly via two vast photographic campaigns conducted in the Champagne region, then in Europe, which led to two major publications (Kœchlin, R., Marquet de Vasselot J.-J., 1900; Kœchlin, R., 1924b). Photography played an essential role in his work as a historian and collector, as a comparative tool that could easily be shared by specialists.

He adopted a formalistic approach, and his highly detailed descriptions developed into analyses (Tomasi, M.,2006, pp. 137–139). He studied certain sources that were contemporary to the objects he focused on, but it is unlikely that Kœchlin explored Japanese sources. He did consult Japanese texts translated for the first generation of connoisseurs of Japanese art, along with the writings of the latter. He was at the forefront of contemporary archaeology and research, and wrote about the latest European and American articles and books. In his opinion ‘(…) with regard to art, and Japanese art in particular, documentation is not the only viable approach’ (Kœchlin, R., 1904, p. 109). He recommended that it was best to start a study by referring to the work itself (Fierens-Gevaert, H., 1903, pp. 143–144). His approach as a historian was influenced by his approach to collecting, which involved creating series. His interest in regional schools, the phenomena of acculturation, and elements of continuity may have been linked to his training in the political sciences (Tomasi, M.,2006, p. 139).

He worked as a historian of Japanese and Chinese arts mainly between 1900 and 1925. In 1901 and 1902, he ran courses about the Japanese arts at the École des Hautes Études Sociales (Tomasi, M., 2006, p. 137). In 1902, he held a conference before the Société Industrielle de Mulhouse about the same theme. After the war, he devoted himself to the ‘Muslim arts’. His publications reflect a new approach to these so-called Oriental arts, which were now studied more scientifically. The idealised vision of a far-off Orient gradually faded. All the same, the approach of the passionate connoisseur took precedence over that of the historian (Luraghi, S. D., 2014, pp. 89, 95). As was the case with most of his peers, the history of these arts was primarily written via Parisian and European private and public collections. Nonetheless, Kœchlin’s publications did contribute to the emergence of a history of Japanese art, which had been undertaken in France since the 1880s and 1890. Nevertheless, it was only in the 1920s that Japanese studies evolved ‘(…) from a cabinet-based Orientalism to research in the field and interchange between specialists in the two countries working in respective academic circles’, a phase Kœchlin was not directly involved in (Marquet, C., 2014).

In his various writings, the history of the arts of Japan and China is combined with that of their discovery and their reception in the West. Kœchlin was keen to diffuse the most remarkable forms of Eastern arts, rather than the ‘Japanese shelf trinkets that abound in Europe’, described as ‘articles made purely for export’ (L’art japonais. Conférence de Raymond Kœchlin…, 1902, p. 1). Like other intellectuals of his era, such as Louis Gonse (1846–1921) and Edmond Pottier (1855–1934), Kœchlin made many parallels between Japanese, Chinese, and Muslim arts. The latter were likened to European and Greek medieval arts. Although they were based on a conception of the Orient marked by a hypothetical aesthetic continuity, these comparisons did not necessarily indicate scientific confusion (Labrusse, R., 1997, p. 288). The idea was to familiarise the European eye with the ‘ornamental grammar’ of these arts. He concluded most of his articles with assertions about the need for French artists to be inspired by Eastern arts in order to create a form of contemporary decorative art, and ‘to place contemporary art on the path traced out by true Japanese art’ (Kœchlin, R.,1903a, p. 132). He defended this goal within the Union Centrale des Arts Décoratifs—one of the first institutions to take an interest in Japanese art, whose board of directors included eminent connoisseurs of Japanese art—and during the exhibitions he took part in. All of these aspects were characteristic of the second generation of connoisseurs of Japanese art and the circle of collectors of Islamic art.

‘Rare taste, great sensibility, and very shrewd too’ (L’Art et les Artistes, 1932, p. 318)

In 1927, Kœchlin stated: ‘I bought my first picture in 1885: it was a small view of Jordan by Ary Renan. I then focused my attention on the Far East’ (Vaugenot-Deichtmann, M., 2011, p. 6). He discovered the art of prints during the exhibition held by Siegfried Bing (1838–1905) in 1890 at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. Thanks to the relations of his wife Hélène Kœchlin, who shared his enthusiasm, Louis Gonse invited him to see his collection and gave them two prints. Kœchlin wrote that ‘my life as a collector commenced that day’ (Kœchlin, R., 1930a, pp. 14–15). In the Hayashi store, he acquired his first prints: two triptychs by Utagawa Hiroshige 歌川広重 (Kœchlin, R., 1930a, p. 18). Kœchlin became friends with Hayashi and Bing and met the collectors in their circle. Initially, he concentrated exclusively on prints, before taking an interest in other forms of Japanese art. In 1900, he acquired his first Chinese ceramic objects dating from the Han epoch, from the Hayashi store (Guérin, M., 1932a, p. 75). Kœchlin focused on arts from the so-called ‘archaic’ periods, which had been added to Parisian collection since the beginning of the nineteenth century. He frequented the boutiques of Japanese, Chinese, and Muslim art owned by Florine Langweil (1861–1958), Charles Vignier, Marcel Bing (1875–1920), Paul Mallon (1884–1975), DikranKélékian (1868–1951), Léon Wannieck (1875–1931), Adolphe Worch (1843–1915), and Loo Ching Tsai (1880–1957). Raymond Kœchlin enriched his collection from the sales of the collections of the first generation of connoisseurs of Japanese art, such as that of Philippe Burty (1830–1890) in 1891, Georges Appert (1850–1934) in 1892, the Goncourts in 1897, and Hayashi in 1902, Charles Gillot (1853–1903) in 1904, and Siegfried Bing in 1906, as well as at the sale of the collection of Jean Dollfus (1800–1887) in 1912. He acquired sabre guards at the Japanese Pavilion in the 1900 Exposition (Guérin, M., 1932a, p. 72). According to Guérin, he acquired few objects on his trips, apart from on the voyage in Egypt (Guérin, M., 1932a, p. 77). At the same time, he frequented the galleries of Paul Durand-Ruel, Paul Rosenberg, and Bernheim Young. He also bought works directly from artists. After the war, he collected less intensively, as he had less financial means and many duties to fulfil with regard to his work with museums. In 1926, he decided to sell forty-eight Japanese and Chinese objects, lacquer boxes, inrō, woodcarvings, bronzes, and cloisonné enamels in the Hôtel Drouot (Objets d’art du Japan et de la Chine provenant des collections Raymond Kœchlin, Edmond et Marcel Guérin, Ch. Salomon, 1926)

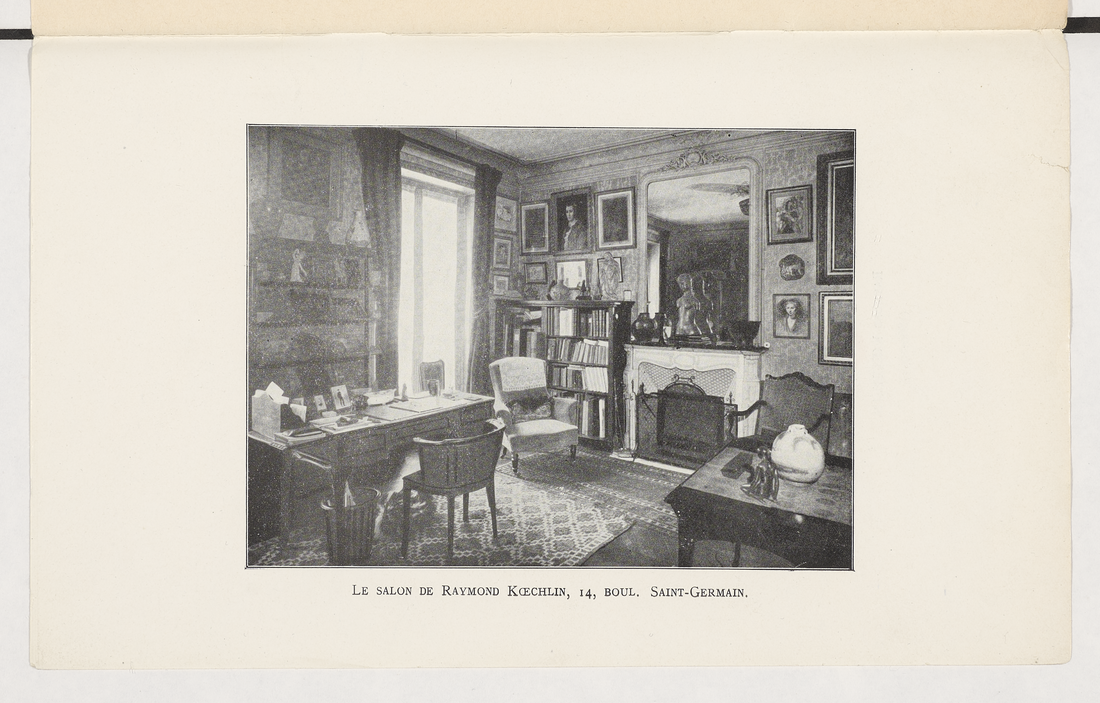

Henri d'Ardenne de Tizac (1877–1932) described Kœchlin’s approach to collecting as follows: ‘He is the most perfect example of the modern connoisseur, who is well informed about everything and careful about everything, but who follows no rules other than his own taste, and no decisions other than his own approval’ (Alfassa, P., Migeon, G., and d'Ardenne de Tizac, H., 1925, p. 93). The eclecticism of his collection matched that of many Parisian dealers, such as Bing and Kélékian and connoisseurs such as Henri Rouart (1833–1912), Michel Manzi (1849–1915), and Jacques Doucet (1853–1929). In his apartment, which was described by Georges Salles (1889–1966), Kœchlin arranged for viewing ancient and modern works from different regions of the world (Salles, G., 1992, pp. 16–19). Objects from ancient Egypt and the medieval West, as well as pictures and nineteenth-century drawings from Delacroix to Maillol were placed alongside works from China, Japan, and Persia. This rapprochement between the arts resulted from the shared notion ‘of the unity of the arts of Asia’ (Kœchlin, R., 1930a, pp. 75–76). The appeal of Japanese, and more generally Oriental arts, was common amongst many connoisseurs who defended Impressionism, which resulted from the same open mindedness, as it represented a break with academic painting. Nevertheless, Kœchlin was not, in contrast with others, a defender of the European avant-garde movements (Labrusse, R., 1997, pp. 280, 287).

Kœchlin frequented the collectors of Far-Eastern and Muslim arts. These milieus interacted with one another and were close to the curators, Parisian dealers, and archaeologists. Relatively small, these circles were pioneering, at least due to their new scientific approach. Indeed, ‘in most of the fields, the connoisseur advanced in often contested terrain, and frequently also in the terrae incognitae of curiosity’ (Alfassa, P., Migeon G., and d'Ardenne de Tizac, H., 1925, p. 93). The second generation of connoisseurs of Japanese art attained the height of their activity between1890 and 1900. Kœchlin’s memoirs, published in 1930, with the title, Souvenirs d'un vieil amateur d’art de l’Extrême-Orient,are an invaluable source of information about this milieu. He described its actors and the enthusiasm with which the collectors interchanged about their latest acquisitions. Kœchlin attended the dinners for the friends of Japanese art, held as of 1892 by Siegfried Bing and continued by Henri Vever (1854–1954) in 1906 (Kœchlin, R., 1930a, pp. 21–22, 59).

When it was established in 1900, Kœchlin became a member of the board of directors, then vice-president of the Société Franco-Japanese de Paris (‘Nécrologie Raymond Kœchlin’, 1932, p. 45.). He held a conference on Japanese art there in 1902 and attended dinners that brought together amateurs, Japanese personalities, and scientists (Société Franco-Japanese de Paris, 1906, p. 54; Kœchlin, R., 1930a,p. 59). In 1901, the Japanese state conferred the Fifth Imperial Order of the Rising Sun on him. (BMAD, AUCAD, R. Kœchlin private archives, Koechlin 1, (no commentary)). In the second half of the nineteenth century,the market for Chinese arts developed in France. Nevertheless, Kœchlin in his Souvenirs, the second part of which was devoted to ‘archaic China’, stated that the attraction for Japan had drawn away the connoisseurs of Chinese art, with the exception of a few persons. All the same, according to him, a new generation of Parisian dealers managed to revive the taste for Chinese art and persuade the collectors, whom he listed (Kœchlin, R., 1930a, pp. 62–67).

The life of his collection

Kœchlin loaned his works for many exhibitions in France and abroad. In 1909, for example, he entrusted the Musée des Arts Décoratifs with eighteen prints for the exhibition of ‘primitive’ Japanese prints. In 1925, he exhibited 133 of his objets d’art at the ‘Exposition d’Art Oriental: Chine, Japon, Perse’ at the Chambre Syndicale de la Curiosité et des Beaux-Arts. He was involved in organising this exhibition, in which he was able to study the influence of China between the eleventh and thirteenth centuries. (Catalogue de l'exposition d’Art oriental, Chine, Japon, Perse, 1924; Alfassa, P., 1932, p. 17; Kœchlin, R., 1925c, 1925e)

In 1894, Raymond Kœchlin gave the Musée du Louvre four Japanese prints by Harunobu (1725?–1770), Choki, Shunsho Katsukawa (1726–1792), and Hokusai (1760–1849), which have been held in the Musée Guimet since 1945 (inventory nos. EO 245 to EO 248) (Diesbach, V., 1993, p. IV; Migeon, G., 1929, p. 53). In 1899, when he joined the board of the Union Centrale, he donated Japanese ceramic wares (inventory nos. 9029, 9030). His regular donations to French museums, followed by his bequest, made him one of the largest donators of Asian arts. As of 1896, Kœchlin successively donated around 7,000 photographs to the Library of the Musée des Arts Décoratifs. This collection included photos of Far-Eastern objects and thirty albums donated in 1903, comprising ‘picturesque views, costumes, and monuments’ from various countries in Asia and America. Certain pictures taken in China bear the mark of the English photographer Thomas Child (1841–1898). Nine albums came from the studio of the Japanese photographer Kusakabe Kimbei (1841–1932). The Médiathèque de l'Architecture et du Patrimoine has an ensemble of Kœchlin’s pictures, which he donated in the 1920s, reproducing several objects of Japanese and Chinese art (Fonds Beaux-Arts/Fine Arts Collection, BAOA00682, 683, 788, 1054, 1263, 1318, and 1319).

In his will of 1926, which was revised in 1930, Kœchlin specified the details of the bequest of his collection to several close friends, including Louis Metman, Paul Goute (1860–1943), Marcel Guérin, Georges Salles, and so on (Diesbach, V., 1993, p. 16). All the same, he planned to bequeath most of his collection to national museums, specifying that the works should bear the mention ‘Legs de M. and Mme Raymond Kœchlin’ (‘Bequest of Monsieur and Madame Kœchlin’). He left them relatively free to choose his works, mentioning simply, amongst others, ‘my Japanese prints, sculptures, and ancient objets d’art from every country with their showcases’ (Préfecture de la Seine, 1932, pp. 178–179). Hence, 124 sabre guards and 126 Japanese prints were bequeathed to national museums. Aside from several specific cases, the Musée des Arts Décoratifs ‘shall keep as a bequest all the objects I placed there and can take whatever works it wishes from those that the national museums do not take’ (Préfecture de la Seine, 1932, pp. 178–179). His ‘Japanese books’ were to be given to the Bibliothèque Nationale, mainly around thirty volumes (DD-3188-4 à DD-3219-4, DD3207, DD3208), some of which are attributed to Hokusai and Masayoshi (1764–1824) and include annotations by Edmond de Goncourt (1822–1896) and Kœchlin. He reserved three Khmer and Javanese works for the Musée Guimet (MG 13230, MG18314, and MG18315). And the remainder of his collection of Western, medieval, and modern art was distributed between the Museums of Fine Art in Lyon, Troyes, Gray, Mulhouse, and Strasbourg. Kœchlin died in November 1931. In May 1932, Metman and Guérin, his testamentary executors, held an ‘Exposition des Collections Léguées par Raymond Kœchlin aux Musées de France’ (‘Exhibition of the Collections Bequeathed by Raymond Kœchlin to French museums’) in the Musée de l'Orangerie, with a focus on Asian art (Betz, M., 1932, pp. 508–509; René-Jean, 1932, p. 3).

Related articles

Personne / personne

Collection / collection d'une personne