LEVI MONTEFIORE Edouard (EN)

A Successful Alliance: The Montefiore and the Cahen d’Anvers

On the evening of November 24, 1855, in his apartment on Place de la Concorde, the banker Meyer Joseph Cahen d'Anvers (1804-1881) celebrated the signing of the marriage contract of his daughter Emma (1833-1901) with Édouard Levi Montefiore (1826-1907). The family hosted a dinner: the minister Hippolyte Fortoul (1811-1856) was invited and noted in his diary that "Israel chose itself and dressed in its Sunday best" (Massa-Gille G., 1979-1989, p. 147). The first marriage among the first Parisian generation of the Cahen d'Anvers family was to be celebrated with the descendant of one of the most prestigious Jewish families in Europe. If the Cahens d'Anvers linked their economic and social success to the patriarch's recent investments and his relations with the trading post of the Bischoffsheims, the origins of the Montefiore family could be traced back to medieval Italy: merchants at the head of a very extensive network, they were linked to the city of Ancona, whose synagogue preserves a ritual silk curtain donated by Leone Judah Montefiore (1605-n.d.) in 1630 (Wolf L., 1884).

Édouard was the son of Esther Hannah Montefiore (1800-1864) and Isaac Levi (or Lévy), who died in Brussels on January 9, 1837. The Montefiore branch from which he descends was active in the banking sector between Livorno, Belgium and the United Kingdom, as well as in trade and shipping to India and Australia (Draffin N., 1987).

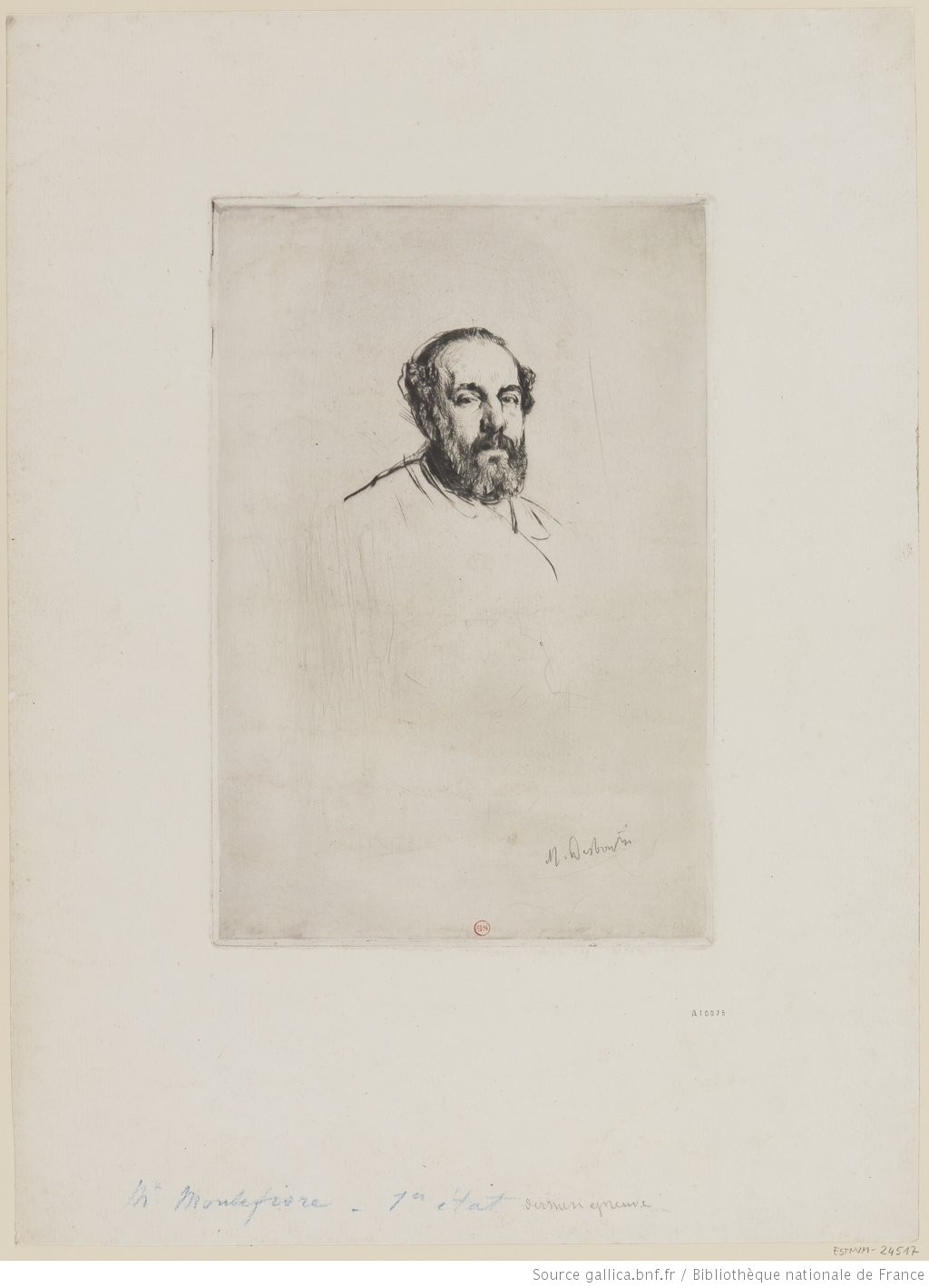

Passionate about engraving, Édouard was a pupil of the famous Bordeaux etcher Maxime Lalanne (1827-1886) [Beraldi H., 1890, vol. 10, p. 111-112; Dugnat G., Sanchez P., 2001, vol. 4, p. 1818]. One of the most famous drypoint engravers of the 19th century, Marcellin Desboutin (1823-1902) dedicated a small portrait to him, of which the Bibliothèque nationale de France keeps a copy (BnF, Estampes et photographie, FOL/EF/415 /I/1). Like his brother Eliezer (1820-1894), Édouard seemed as gifted for drawing as for finance. It is to his hand that we owe the illustrations of the Notes de voyage written by Louise Cahen d'Anvers (1845-1926) on the occasion of her crossing of Latin America (Paris, coll. Monbrison, 1893), or a beautiful album of sketches made in the Swiss Alps (coll. Leroy-D’Amat, Albums de dessins d’É. Levi Montefiore, 1883-1894). As for his public production, he adapted 25 drawings by Eugène Fromentin (1820-1876) into engravings, which were accompanied by a text by Philippe Burty (1830-1890) (Burty P., 1877).

The union of Édouard Levi Montefiore with Emma Cahen d'Anvers — whose features are known to us thanks to a portrait preserved by one of her descendants (Paris, Private Collection) — reinforced the presence of the two families on the European markets. In finance as well as in their real estate choices, the Montefiores and the Cahens d'Anvers adopted similar policies. In Brussels, Édouard's family owned a sumptuous mansion, at 35 rue des Sciences, the current seat of the Belgian Council of State. While the Cahen d'Anvers had several chateaux near Paris, the Montefiores preferred Wallonia: the couple regularly visited Georges Montefiore (1832-1906) at the Rond-Chêne estate, in Esneux (coll. Laroque family, Photographie de famille au Rond-Chêne, 1885 ca). For their part, Édouard and Emma set up a ‘country house’ in Coucy-le-Château-Auffrique (Aisne) as their summer residence. Here, at the Domaine de Moyembrie, their grandson Seymour de Ricci (1881-1942), a great scholar, historian and renowned epigraphist, took his first steps (Ramsay N., 2013).

Family, Social Life, Religion

Moving between France, Italy and Belgium, the Montefiores inhabited an upscale environment familiar to Emma's parents. The two families were the embodiment of upper class Europeans with diverse interests. Like several members of the Cahen d'Anvers family, Édouard Levi Montefiore was portrayed by one of the most famous artists of the Third Republic, Léon Bonnat (1833-1922) [Montréal, coll. go.]. Since 1882, a friendship bound him to Ernest Meissonier (1815-1891). At this time, one of the couple's children came home with two of the painter's paintings, bought "from a cane and umbrella merchant near Saint-Augustin": they had to be returned to the painter the day he presented himself at the Montefiore's, accompanied by a police commissioner whodeclared that his works had been stolen (Montefiore R., 1957, p. 24).

Another prestigious friendship was formed between Édouard, his brothers, and Louis Pasteur (1822-1895). Knowing of the family's overseas activity, the scientist went to their home on Avenue Marceau around 1893, to "spread his bitterness", at the end of an unfinished attempt to reduce the population of Australian rabbits with the introduction of myxomatosis (Id., p. 30-31).

Equally fruitful relationships link Édouard Levi Montefiore and his wife to the composer César Franck (1822-1890), who gave singing lessons to their daughter, or to Asian art aficionados such as their sister-in-law Louise Cahen d' Antwerp, Philippe Burty, Edmond Taigny (1828-1906), Henri Cernuschi (1821-1896), Charles Ephrussi (1849-1905) and Louis Gonse (1846-1921).

In Paris, in the second half of the 19th century, alongside the Rothschilds, the Ephrussis and the Pereires, the Bischoffsheims, and the Camondos, the families Montefiore and Cahen of Anvers earned their standing on the stock exchange as well as in the salons and in prestigious clubs, rubbing shoulders with a conservative aristocracy that rarely hid its contempt for the Jews.

From the forty-six years of marriage of Édouard Levi Montefiore and Emma Cahen d'Anvers were born numerous descendants, despite two terrible early losses: Anna (1860-1863) and Alice (1863-1869) survived only three and six years respectively. Hélène (1857-1932), Georges (1864-1903) and Raoul (1872-1963) ensured the continuation of the line (Legé, A.S., 2022).

Through one of the marriages of this second generation, that of Raoul with Jeanne Machiels (1877-Auschwitz, July 23, 1943), the Cahens d'Anvers and the Montefiores further strengthened their social network: Jeanne was the granddaughter of Joseph Alfred Cahen (1809-1890), the younger brother of the patriarch of the Cahen d'Anvers. At the same time, the marriage of Hélène Montefiore with James Herman de Ricci (1847-1900), a descendant of a Florentine noble family, was an expression of a formal success as well as of exogamy, marriage between religions. Georges, for his part, celebrated his union with Esther Antokolsky (1875-n.d.), daughter of the great Lithuanian-Russian sculptor Mark Antokolsky (1843-1902) [Legé, A.S., 2022, p. 57-59, 68-71].

Despite his daughter Hélène’s mixed marriage, Édouard Levi Montefiore’s registration with the Society for Jewish Studies (Actes et Conférences de la Société des études Juifs, t. 1, 1886. p. 82) as well as the epigraph "שָׁלוֹם" (shalom) adorning the family tomb (cimetière de Montmartre, 3e division, no 250) bear witness to a deep attachment to Jewish traditionthat was rarely noted among the various branches of the Cahen d'Anvers family. Within an elite minority, which fought for its integration into an often malicious Catholic society, the choice of a Yiddish inscription, short and positive, sends a very clear message: Édouard Levi Montefiore was open about his origins and identified himself with his roots.

The Hôtel de l’Avenue Marceau and its Collections

In 1881, after the death of Emma's father, Meyer Joseph Cahen d'Anvers, the couple left the Hôtel Cahen d'Anvers in the rue de Grenelle to settle at 58, avenue Marceau. Here, for 600,000 francs, Édouard Levi Montefiore bought a vast mansion that had once belonged to Edme Armand Gaston, Duke of Audiffret-Pasquier (1823-1905). Now replaced by a building from the second half of the 20th century, the old building is described by Raoul Montefiore in his diary: "When we had passed the carriage door, we found ourselves under the vault with the rooms of the concierge to our left […]. To the right, a vestibule and, further on, a large kitchen. After the vault, a small garden with an exit onto Rue Bassano […]. A staircase with wooden banisters led upstairs. It was all adorned with Kakemonos, one, of great beauty, represented a tiger. The dining room was on the first floor, with a balcony at the corner of rue Bassano, where we were very comfortable on summer evenings. Then followed a small drawing room with blue silk hangings where there was a very beautiful Louis XVI mantelpiece […]. Next came the large living room with gilded paneling, then [Édouard’s] study that occupied two floors with a gallery of running wood at the height of the second floor. Behind was a gallery where [he] had assembled his Japanese collection, then the billiard room” (Montefiore R., 1957, p. 5, 22).

A beautiful photograph taken in the library allows us to appreciate the variety and quality of objects that Édouard Levi Montefiore collected (Id., p. s.n.). On a huge Renaissance fireplace stands the severe silhouette of a white marble bust, probably portraying a family member. Under the lights of a bronze chandelier, several pieces of 18th-century furniture arranged on Persian rugs hold lacquerware and ceramics as well as richly decorated screens, and even a samurai helmet and katanas. Comfortably seated in his armchair, a sword sheath in his hand, the collector seems to be observing paintings springing up at the photograph’s edge, near a file containing drawings. Behind him appears a painting by Eugène Fromentin, Oasis à Laghouat, dating from the 1860s and based on a photograph taken by the artist in Algeria. Under the title of Forêt de palmiers, this canvas had been part of the collections of Meyer Joseph Cahen d'Anvers (sold for 5,000 francs; AN, Min. cent., LXIV, 908, 1881, 19 September). Sold at Christie's New York in 1995, it is now in a private collection (Thompson J., Wright B., 2008, p. 299, 562).

At least one additional painting arrived at the avenue Marceau after the death of Emma Cahen d’Anvers’s father: a version of the famous portrait of Napoleon premier consul by Jean-Baptiste Greuze (1725-1805). In this painting, the future Emperor of the French, standing in his office, turns his back towards an open window that allows a glimpse of the city of Antwerp. For a family linking its power to this commercial capital on the Scheldt, the choice of such a painting was not insignificant. Meyer Joseph had acquired it in 1866, at the sale of the Marquis Valori Rustichelli (71 × 55 cm ; Catalogue des tableaux […], 1866, cat. 96 ; Mauclair C., Martin J. et Masson C., 1906, cat. 1062). It was probably a sketch for the large portrait in the Napoleon Museum, sent to Versailles in 1835 (242 × 177 cm; inv. MV 4634).

As with many art collectors, Edouard Levi Montefiore's Asian objects were placed in settings deeply linked to the 18th century. While some modern paintings underline the owner's attention to the arts of his time, other canvases, architecture and furnishings highlight the family's attachment to the style of the Ancien Régime, a universal symbol of "good taste".

Once again, Raoul Montefiore's memoirs provide us with a colourful picture of what this collection meant to his family. In Paris, Édouard, his father, was among the first to understand the finesse of Japanese art, alongside amateurs such as Gonse, Burty, and Cernuschi. His collection was well known. Often, he returned home with "a new object that he [just] bought", while his wife “roll[ed] her eyes". His rooms house "delicate ivory figurines, each of which [tells] a story", "lacquered medicine boxes", and “sword in sheaths". One of these blades, with its black lacquer case, dates from the tenth century and was estimated at "10,000 francs" (<i>Cfr.</i> Gonse, L. 1883, p. 418, cat. 11). In an antechamber is "an all-lacquer saddle with enormous stirrups and, beside it, two men-at-arms with coats of mail." Beyond their value on the market, these objects, freely available to be looked at and touched, provided the couple's guests the experience of weighing an old vase in the palm of the hand, touching the patina of lacquer, or feeling the coldness of a sword blade or a bronze figurine: "The Count of Jansé once borrowed a suit of armour for a costume ball" (Montefiore R., 1957, p. 22, 76-77).

Among the Montefiores, the tradition of dressing up in costume – ranging from the historical ball to the masquerade – involved all branches of the family and touched their entire environment. Once at a ball at Henri Cernuschi's, for example, Édouard Levi Montefiore “dressed as the master of the house", while his son Raoul was disguised "as a flower girl" (Id., p. 75).

The Collection Montefiore and the Retrospective Exhibition of Japanese Art

Édouard and his wife gladly opened their doors to aficionados, but Édouard also enhanced their collections’ influence through loans. In 1883, for example, more than 200 of their objects appeared in the Exposition rétrospective de l’art japonais, organized in the Galerie Georges Petit by Louis Gonse (Gonse, L. 1883, pp. 415-436, cat. 1-221). In the catalog, the section dedicated to the Montefiore collection opens with a beautiful engraving of a samurai helmet and closes with that of a sabre hilt with two dragons. Between the two illustrations, a multitude of Japanese objects from various periods beguile readers. Among eleven lots of bronzes are a praying mantis and a square planter bearing the signature of Murata Seimin (1781-1837) and a cylindrical vase on a stand, signed by Kimura Toun (1800-1870 ca). Several sections are devoted to items of a military nature. Twelve complete sabres and a scabbard from the 18th century are followed by a compendium of 108 sabre hilts in various metals, divided into 52 lots, as well as 8 suits of armour and helmets and a small collection of daggers and knives. Édouard Levi Montefiore also had a collection of twelve netsuke in metal, in the shape of animals or Buddhas, that bore the signatures of several artists, including Kyudaisai Temmin and Ho Riomin (early 19th century). The catalog further mentions 56 ivory objects, 22 carved wooden objects and a collection of 13 lacquered inrô. As evidenced by the dossier prominently displayed in the photograph by Édouard Levi Montefiore in his library, the collection loaned to the Galerie Georges Petit also included 7 lots of albums and works on paper, including 2 volumes of views of the coasts of Japan and 47 depictions of ronin, by Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1797-1861). Two final sections are devoted to fukusa and kakemono, among which is a monkey under snow-covered banana leaves, bearing the signature of Mori Sosen (1747-1821).

In his choices, Édouard Levi Montefiore seemed to express a certain preference for objects deriving from the martial tradition of the Land of the Rising Sun, without however neglecting landscape design, lacquerware or Chinese porcelain. While the latter easily found its place at the house on avenue Marceau, as it did in many residences of the time, the attention that Montefiore devoted to Japan made him as a precursor of Japonisme. Japan's emergence from isolation dated back only to 1853: France signed a "friendship and trade" agreement with the shogunate five years later. More in-depth research on the collection of Édouard Levi Montefiore remains to be carried out. Nevertheless, the objects exhibited at the Galerie Georges Petit in 1883 offer a glimpse of what was to become one of the largest collections of Japanese art in France. Collected in the space of three decades, it demonstrates the owner's taste, open-mindedness and cosmopolitan upbringing.

Related articles

Personne / personne

Collection / collection d'une personne