CAHEN D'ANVERS Louise (EN)

From Trieste to Paris, Louise de Morpurgo and the Cahen d’Anvers Family

The interest of the Cahen d’Anvers family in the affairs of the Italian peninsula is reflected in the marriages of Louis (1837-1922) and Raphaël (1841-1900) with two descendants of the Morpurgo family. Established in Trieste for nearly three centuries, this prestigious Ashkenazi house had obtained the barony, through family member Carlo Marco (1827-1899). In the same year, 1866, patriarch Meyer Joseph Cahen d’Anvers (1804-1881) became an Italian count. Luigia (1845-1926) and Irene (1849-1890), later known as Louise and Irène, were the daughters of Giuseppe Morpurgo (1816-1898) and Elisa Parente (1818-1874) [Catalan T., 1997, p. 165-186]. Founded in 1812, Morpurgo & Parente was an outstanding lending institution that wasconnected with the development of railroads, the construction of the Suez Canal, and the creation of the Trieste-Bombay maritime line. By the mid-19th century, Giuseppe Morpurgo had taken over as head of the Banca Austro-Orientale and had become one of the Rothschild's foreign correspondents (Polsi A., 1993, p. 271).

The union between Louis Cahen d'Anvers and Louise de Morpurgo was celebrated in Paris on June 30, 1868 (Montefiore R., 1957, p. 58). It marked the beginning of a long family collaboration that unfolded on both sides of the Alps, particularly with the Morpurgo family’s participation in Édouard Cahen d’Anvers’s investments (1832-1894) in the real estate sector of post-unification Rome. By simplifying a very complex reality, the marriage alliances of the Cahen d'Anvers with the Morpurgos, or even with the Warschawsky, the Montefiore and the Camondo, form the basis of an almost self-sufficient economic microcosm. Marriage policies allowed the families concerned to mould themselves as financial dynasties, with branches all over Europe, headed by a relative. The fact that this took place within the Jewish high society at the time should not be surprising: far from indicating a practice of endogamy consistent with some conspiracy theory, the tendency had as much to do with peer recognition as with the impossibility of opening up to a Christian entrepreneurial class that was anything but positively disposed towards them (see Grange C., 2005 and Legé AS, 2022, p. 55-83).

Resolutely Parisian, the generation of children of Louise Morpurgo and Louis Cahen d’Anvers strove with varying degrees of success to consolidate the network or to cross the barriers of blood through mixed marriages. Robert (1871-1933) and Charles (1879-1957) celebrated unions with descendants of the Warschawsky and Lévy families. Irene (1872-1963), whose features are known to the general public through the portrait La Petite Fille au ruban bleu by Renoir (1880, Zurich, Bührle collection, inv. 90) was given in marriage to Moïse de Camondo (1860-1935). Alice (1876-1965) and Élisabeth (1874-1944) - also portrayed by Renoir in the painting Rose et Bleu (1881, Sao Paulo Museum of Art, inv. 99P.1952) - became associated with two great families of the Christian aristocracy: the Forceville and the Townshend.

During the First World War, Louis and Louise Cahen d’Anvers found refuge in Norfolk with a member of one of these families, son-in-law Charles Vere Ferrers Townshend (1861-1924). Louis and Louise then returned to France and transformed the château de Champs into a military hospital (Serrette R., 2017, p. 175-176).

Portraits of a Salonnière

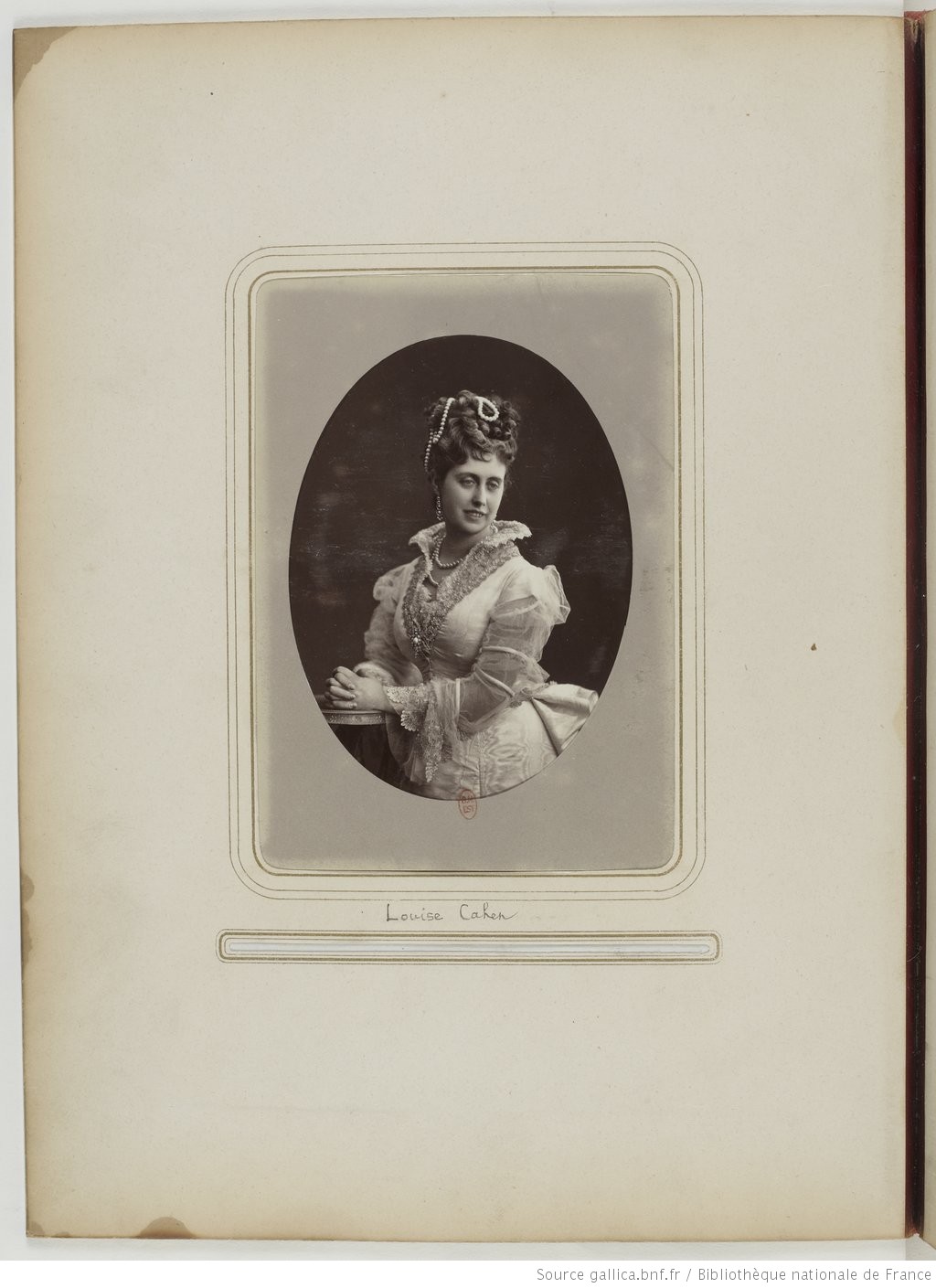

Louise Morpurgo - whose features are known to us through a series of photographs (BnF, Estampes et photographie, 4/NE/74) as well as through several painted portraits - held a salon every Sunday in summer. At 2, rue de Bassano, or in the rooms of the château de Champs, “a small group of friends and many acquaintances” formed what her daughter-in-law Sonia Warschawsky (1876-1975) defined as “an ultra-socialite assembly” (Cahen d'Anvers S., 1972, p. 47). Since arriving in Paris upon her marriage in 1868, Louise surrounded herself with a remarkable body of artists, diplomats and men of letters. She frequented Guy de Maupassant (1850-1893) and Marcel Proust (1871-1922). She was close to Alexandre Natanson (1867-1936), and artists and musicians such as Jacques-Émile Blanche (1861-1942), Federico de Madrazo (1815-1894), Charles Malherbe (1853-1911) and Fernand Halphen (1872-1917). Renowned collectors such as Charles Ephrussi (1849-1905), Edmond Taigny (1828-1906) and Louis Gonse (1846-1921) frequented her salon. Among the guests of the rue de Bassano was also a character who shared with Louise a deep love for travel: Viscount Florimond de Basterot (1836-1904). The perfect representatives of a cosmopolitan spirit mixing curiosity within appetite for risk, Louis Cahen d'Anvers and his wife traveled incessantly during the last decades of the 19th century. On several occasions they explored Italy - most notably in the company of prestigious guests such as Joachim, 4th Prince Murat (1834-1901) - but they also sought out faraway destinations. An interesting account written by Louise in 1893 shares the details of a trip the couple took across Latin America (Paris, Private Collection, Notes de voyage).

Among the guests of the Cahen d'Anvers was a writer who deserves special mention due to the importance of the relationships he forged with the family: Paul Bourget (1852-1935). Louise and her sisters-in-law Loulia and Marie Warschawsky bonded with the poet through friendships which mixed intellectual exchanges with a more or less assertive eroticism. They were granted the nicknames beautiful and good or angel, her perfection, and The Parthian (Mansuy M., 1985, p. 58). From 1881, Bourget entrusted Louise Cahen d´Anvers with his travel memoirs. These Memoranda, indebted to a Stendhalian practice, supported him in the drafting of Sensations d'Italie (1891) and testify to the level of confidence that bound the writer to his patron (BnF, Ms., NAF 13714-13719).

Apart from Bourget, Louise and her husband's most assiduous suitor was undoubtedly Léon Bonnat (1833-1922). Between 1875 and 1903, the painter produced at least six portraits of members of the Cahen d’Anvers family (Saigne G., 2017, cat. 100, 101, 101E, 102, 103, 104, 105). In 1893, showing the timeless nature of the beauty of his hostess, he painted a portrait of Louise in profile which took up the forms and framing of a painting that Carolus-Duran (1837-1917) had painted in 1880 (Saigne G., 2017, cat. 104; Carolus-Duran, 1919, n. 120). A few years later, Bonnat again saw his work enter in dialogue with that of his colleague in the house of the Cahen d’Anvers: in 1901, he painted a ceremonial portrait of Louis, which serves as a pendant to one that Carolus-Duran had dedicated to Louise in 1875 (Saigne G., 2017, cat. 105; Carolus-Duran, 1919, n. 119). Against a dark background, comfortably seated in an armchair, Louise rests her elbow on a golden cushion: her position, her gaze and her elegance refer to the acquired status and dignity of her role as patron.

At once shocked andseduced by the countess’s aplomb, “her head abandoned to the side, showing at the top a curl of hair that resembled a nest of snakes”, Edmond de Goncourt devoted to her a description which, once stripped of the prejudices, helps comprehend her strength of character (Goncourt E., 2004, II, p. 858). Louise’s taste for the arts and sciences, as well as her ability to forge fertile relationships within the political circles of her time, contributed to the family's social rise. Suffering from arteriosclerosis, Louis Cahen d’Anvers passed away on December 20, 1922 (AP, état civil, 16D/125 n. 2377). His will, dated May 8, 1918, entrusted his wife with “the usufruct during her life, with exemption from deposit and employment, of half of the movable and immovable property” of her estate. Ownership of his mansion passed to their eldest son, Robert, while that of the château de Champs-sur-Marne went to the younger, Charles (APR, Ét. Not. Casagrande and Labrousse, s.c.). After Louis's death, Robert left his apartment at 83 avenue Henri-Martin to settle with his mother. Louise de Morpurgo passed away on June 21, 1926, in the hotel on rue de Bassano, surrounded by her relatives and by the works of art she had carefully collected over fifty years.

Two Residences, One Collection

After several seasons renting the château de La Jonchère in Bougival (Yvelines), Louis and Louise Cahen d'Anvers rose to the rank of lords during the summer of 1895: on August 5, Louis bought from the Santerre family an estate of 318 hectares, located on a loop of the Marne (AN, Min. cent., LXIV, 989, 1895, August 5). Forty years later, his son Charles donated the estate to the French state, which classifies it as a historical monument, by decree of August 13, 1935 (Paris, CNM, Service de doc., dossier Champs-sur-Marne). The chateau had been built between 1703 and 1708 for one of Louis XIV's financiers, Paul Poisson de Bourvallais (†1719), by architects Pierre Bullet (1639-1716) and Jean-Baptiste Bullet de Chamblain (1665-1726) [Serrette R., 2017]. Its restoration was entrusted to the office of the Destailleur architects, where Hippolyte (1822-1893) was succeeded by his son Walter-André (1867-1940). Through decorations commissioned by Louis-César de La Vallière (1708-1780) from Christophe Huet (1700-1759) around 1747, the chateau’s rooms express the earliest example of Europe’s appetite for Chinese art in the 18th century (Garnier-Pelle, Forray-Carlier and Anselm, 2010, p. 97-111). Remarkable vestiges from the time when the chateau was inhabited by Madame de Pompadour (1721-1864), these “chinoiseries” were in dialogue with the more recent acquisitions of Louise and her husband. By evoking the ‘exotic’, they responded perfectly to the taste of a financial bourgeoisie inspired by the customs of the aristocracy. Through the ostentation of luxury, the enhancement of their internationalism and the pleasure of collecting, Louise and Louis expressed their economic and social success. In a deeply anti-Semitic France, integration also required careful real estate choices. Completed in 1883, the couple's Parisian home rose up on the hill of the Étoile, at number 2 rue de Bassano; the architect Hippolyte Destailleur was in charge of its construction in 1880. Most attentive to the development of comfort, Destailleur combined eighteenth-century aesthetics with the novelties of an industrial revolution that radically changed the modus vivendi of the European elites. With its neo-Louis XIV style and the modernity of its services, the Cahen d'Anvers mansion showed the world the elegance of its sponsors and the power of their resources.

At the corner of rue de Bassano and rue Bizet, the Salon de Madame - also called the "round boudoir" - traces the proportions of the small living room on the ground floor. A mantelpiece is surmounted by a clock attributed to Clodion (1738-1814), representing Les Trois Grâces (Cahen d’Anvers S., 1972, p. s.n.). Connected to the hall by a corridor, the boudoir serves as an element of liaison between the male and female spaces on the first floor. It is probably this room that should be recognised in the drawing that closes Louise's travel diary in Latin America (Paris, Private Collection, notes de voyage). In the lines sketched by Édouard Lévi Montefiore (1826-1907), we recognise objects today in the chateau of Champs-sur-Marne: the Portrait présumé d’Anne Louise Bénédicte de Bourbon-Condé, duchesse du Maine and two terracotta busts of Mars and Minerve (inv. CSM1935003718 and CSM1935002780-81). In the same room was a display case filled with porcelain from Saxony, including a box that was part of the Max Kann collection (Champier V., 1879, p. 143). Further on, a painting by Hubert Robert and a small portrait by Greuze testify to a taste for 18th-century painting which took off again thanks to connoisseurs such as the Goncourts. Along with other paintings and a selection of tapestries, these two canvases served as the backdrop for a large collection of Japanese enamels and Chinese porcelain from the Ming, Kang-Xi, Yong-Cheng and Qianlong eras. Carefully collected in display cases, these objects are the fruits of research carried out by Louise Cahen d'Anvers in Paris, at auction halls and with antiques dealers such as Louise Mélina Desoye née Chopin (1836-1909) and Philippe Sichel (1840- 1899).

Sociability and Collection

The exotic nature of Japanese and Chinese creations charmed the cosmopolitan entrepreneurs living at the dawn of globalisation. Through the actions of Louise and her nephew Hugo, the Cahens d’Anvers fell squarely within this category of enthusiasts. Louise Morpurgo’s passion was probably deeply rooted in the rates of her original family (Crusvar, L., 1998), but it was also developed through the influence of several connoisseurs. Two great lovers of oriental art, Edmond Taigny and Louis Gonse, were close friends of the countess, and a third - Charles Ephrussi - was probably her lover. The first, whose collections were partially dispersed at the Hôtel Drouot in 1893, was one of the usual guests at the chalet of Albert Cahen d’Anvers (1846-1903) in Gérardmer. He regularly frequented the rue de Bassano: the “noble and great love” he expressed for Louise did not fail to arouse the jealousy of Paul Bourget (BnF, Manuscrits, NAF 13718, f.8).

The second, Louis Gonse, was one of his era’s greatest admirers of oriental art. His friendship with Louise was one of several within the entourage of the Cahen d'Anvers: he frequented Henri Cernuschi, the Camondos and the Montefiore. Nevertheless, according to the memoirs of Sonia Warschawsky, it was especially Ephrussi that introduced Louise“to Chinese blue porcelain, who enchanted her, encouraging her to form such collections when they had not yet come back into fashion” (Cahen d'Anvers S., 1972, p. 108). For her part, Louise supported her friend in the creation of a collection of 264 netsuke, whose story became the subject of a famous book, La Mémoire retrouvée by Edmund de Waal (Waal E. de, 2011). Ephrussi, who was very close to Philippe Burty (1830-1890) and to the community of the Gazette des beaux-arts, had a significant influence in the formation and circulation of his friend's collections. In 1878, for example, he advised Louise Cahen d’Anvers to lend some objects for the exhibition of Japanese lacquers that took place at the Trocadero Palace, during the third Exposition universelle in Paris. Through loan mechanisms and the resulting visibility, the collection ensured a certain social influence for its owner. On this occasion, Ephrussi published a review in the pages of the Gazette des beaux-arts: out of a total of eight illustrations, three show his friend’s objects. Produced by Charles Goutzwiller (1819-1900), these facsimiles show a white lacquer box “of surprising delicacy”, a Japanese cabinet, and a gold lacquer box in the shape of a fan (Ephrussi C., 1878, p. 957, 960-961).

Five years later, in 1883, Louise lent other objects for the Exposition rétrospective de l’art japonais, organised in the rooms of the Galerie Georges Petit by Louis Gonse. In his catalog, Gonse mentions two Imari ceramics belonging to Louise, as well as 64 other entries, corresponding to lacquered objects dated from the 13th to the 19th centuries. Fifty boxes of various shapes sit alongside two trays, an inkwell, a coin bank, a sake cup, a candy box, an incense burner, and a tea powder pot, as well as four small cabinets, a small goblet and four trays in black lacquered copper, with views of Rome in gold (Gonse L. 1883a, p. 153-165, cat. 1-64, 65-66). Also in 1883, this last set was published by Gonse in the volume Japanese Art. Particularly remarkable for their syncretic character, these four panels were “commissioned from Japan by the Jesuits” (Gonse L. 1883b, p. 215). In their forms, we recognise the “Palace of the Marquis Muti, behind the Church of the Holy Apostles”, a “view of the Barberini Palace”, a “view of the Church of St. Ignatius” and finally a “view of the place of Monte-Cavallo” (Gonse, L. 1883a, p. 157, cat. 15). Another particularly remarkable lacquerware object was published by the same author in the second edition of L’Art japonais (1886): "A round box, decorated on top with two figures on horseback" bears all the signs in the manner of Hon'ami Koetsu 本 阿 弥 光 悦 (1558-1637), very similar to an inkwell which bears “the signature and the seal of the master” (Gonse L., 1886, p. 264-265).

A Taste for the Ancien Régime

Louise Morpurgo's taste for the arts of the Far East was not completely foreign to her husband's passion for the Ancien Régime. From the chateau de Champs-sur-Marne to the salons of the rue de Bassano, the figures of Madame de Pompadour and Marie-Antoinette seem to link Louise's interest in the Orient to the splendours of the 18th century. In 1880, while Louis Cahen of Antwerp was planning the construction of his mansion, Charles Ephrussi published a full and commented transcription of the inventory of the oriental collections of Louis XVI's wife (Ephrussi C., 1880). Louise had a copy of this volume “cordially offered” and dedicated by “her respectfully affectionate Charles” (Neauphle-le-Château, Leroy collection).

Louise's passion for porcelain was firmly rooted in the tastes of her time, while anticipating a fashion that would spread throughout Europe in the following decades. Art and patronage placed the Cahens d’Anvers at the top of a social pyramid shaped by several factors, including topicality and the prestige of appearances. Collecting items that had once satisfied the tastes of a queen conferred a certain allure to the wife of a banker. The suggestion that Louise sought to rekindle the “royalty” of these collections by creating her own contemporary collection is not far-fetched. In L’Art japonais, Louis Gonse already remarks how Mme Cahen d'Anvers had “resumed in a very superior manner the work of Marie-Antoinette” (Gonse L., 1883b, p. 219). The book enjoyed great editorial fortune; in its pages and in the eyes of its readers, the name of the Cahen d'Anvers was once again associated with the past grandeur of the Ancien Régime, to which the family seemed constantly to aspire. Contributing to the influence of her line, Louise Cahen d’Anvers became known for the value of her collection, the originality of her taste and her activity as a patron. In a society that often denied women any cultural recognition, the countess’s involvement in the arts hinted at a certain desire for revenge. Through the autonomy of her aesthetic choices Louise Cahen d’Anvers affirmed her independence, her identity, and her “distinction”.

Related articles

Personne / personne

Collection / collection d'une personne