MAZARIN duchesse de (EN)

Biographical article

Louise-Jeanne de Durfort de Duras was born in Paris on 1September 1735, to Emmanuel-Félicité de Durfort, Duc de Duras (1715–1789), a peer and marshal of France, and Charlotte-Antoinette de La Porte Mazarin (1719–1735), the daughter of Guy-Paul-Jules de La Porte Mazarin (1701–1738), descendant of Hortense Mancini (1646–1699), the niece of the famous Cardinal Mazarin (1602–1661). Charlotte-Antoinette died shortly after the birth of her daughter, who inherited the title of Duchesse de Mazarin and an incredible fortune. Louise-Jeanne married her first cousin, Louis-Marie-Guy d’Aumont (1732–1799), the son of Louis-Marie-Augustin, the fifth Duc d’Aumont (1709–1782), the famous collector and Premier Gentilhomme de la Chambre du Roi (First Gentleman of the King’s Bedchamber). The marriage contract was drawn up on 10 July 1746 (AN, MC, AND/XXIII/778), but, due to their consanguinity, they required papal dispensation and the religious marriage was finally celebrated in December 1747. From this union was born Louise-Félicité-Victoire d’Aumont, Duchesse de Valentinois (1759–1826), who married the Prince of Monaco, Honoré IV Grimaldi (1758–1819).

By birth, the Duchess belonged to the highest nobility of the French court and lived in Versailles for many years. Her contemporaries described her as a very beautiful woman, who was tall and had magnificent eyes, but who was also overweight (Bachaumont, L., 1783–1789, 25 March 1781). She held the position of dame ordinaire to Madame Adélaïde (1732–1800), the fourth daughter of king Louis XV, between 1756 and 1760. Memorialists claim the Duchesse had many lovers—with whom she was financially generous—, including Antoine de Malvin de Montazet, the Archbishop of Lyon (1713–1788), Louis-François de Bourbon, Prince de Conti (1717–1776), and Claude-Pierre-Maximilien Radix de Sainte-Foy (1736–1810), the Surintendant des Finances of the Comte d’Artois (1757–1836) (Bachaumont, L., 1783–1789, 6 March 1773).

Despite being prohibited from managing her property in 1763, she continued to spend recklessly to refurbish her luxurious and numerous residences in Paris, Chilly, Versailles, Fontainebleau, Compiègne, and many other locations. She died in Paris, in her mansion on the Quai Malaquais, on 17 March 1781, leaving behind one of the finest and largest collections of objets d’art and curiosities … that matched her debts. Indeed, her daughter, the Duchesse de Valentinois, her sole heir, initially rejected her heritage under benefit of inventory and it took several years for the Duchesse de Mazarin’s estate to be settled (Faraggi, C., 1995, p. 75).

The collection

In 1760, as a result of Louis-Marie-Guy d’Aumont’s large debts and dissolute life, the Duchesse de Mazarin requested the separation of property with her husband (AN, MC, AND/XXIII/778). Subsequently, several sales were held of the furniture from their residences in Paris, Versailles, Compiègne, and Fontainebleau, but the Duchesse made a bid for the ensemble for 160,356 livres (AN, MC, AND/XXIII/778). Following this separation, the Duchesse de Mazarin led the life of a spendthrift in order to gain possession of the most innovative and aesthetic interior decors, furniture, hard stone articles, porcelain objects, lacquer objects, jewellery, and gold and silver wares. On 19 July 1767 (AN, MC, AND/XXIII/690), she acquired from Louis-François de Bourbon, Prince de Conti, for the sum of 400,000 livres, the Hôtel de La Roche-sur-Yon, called the Hôtel de Lauzun, located in Paris at nos. 11–13 on the Quai Malaquais, which became, along with the family château in the city of Chilly-Mazarin (Essonne) two veritable showcases for her collections. The Parisian mansion, built in 1630 by Clément Métezeau (1581–1652), comprised a main building and a single wing; this residence was not habitable in 1767. This explains why the Duchesse began, between 1767 and 1774, an initial campaign of work that was directed by the architect Pierre-Louis Moreau-Desproux (1727–1794): the idea was to renovate the building, including the roof, courtyard, and heating system and renew the interior decor. The latter was initially carried out by Pierre-François Maurisan, then, as of 1769, by Gilles-Paul Cauvet (1731–1788); both worked on the carvings of the mansion’s panelling (Faraggi, C., 1995). Painters and gilders, such as the widow Bardou, and Huet, worked on the paintings. Then, as of 1774, the architect François-Joseph Bélanger (1744–1818), aided in 1777 by Jean-François-Thérèse Chalgrin (1739–1811), carried out the second campaign of refurbishment until 1781. In preparation for her daughter’s wedding with the Prince of Monaco in 1777, the apartments of the future Duchesse de Valentinois were renovated with the latest arabesque decorations executed by the sculptor Nicolas-François Lhuillier (1736–1793) and the painter Jean-Marie Dussaux. The carpenters, Saint-Georges (1723–1790), Pluvinet (?–1793), Jean-Baptiste Boulard (1725–1789), and Louis-Charles Carpentier (circa 1730–1788), provided most of the mansion’s seating (Faraggi, C., 1995). For her furniture, the Duchess solicited the help of famous marchands-merciers (dealers) who were supplied by the finest cabinetmakers, such as Pierre Garnier (1726–1800), Jean-François Leleu (1729–1807), Martin Carlin (1730–1785), and Joseph Baumhauer (?–1772). It was in the grand salon, or grand gallery, as of 1778, that the marble artisan Adam, the sculptor Jean-Joseph Foucou (1739–1821), and the famous bronze chaser and gilder Pierre Gouthière (1732–1813) played the most important roles (Vignon, C., and Baulez, C., 2016). Indeed, they created for the salon an ensemble in turquin blue marble adorned with gilt bronzes made by Gouthière, comprising two pedestals (private collection), a fireplace decorated with female fauns (formerly in the Château de Ferrière), and a console that remained unfinished upon the death of the Duchesse (Frick Collection, New York, 15.5.59). Gouthière also fitted the salon with a pair of bras de lumière with five poppy flower branches (the Musée du Louvre, Paris, OA 11995–11996) (Duclos, C., 2009) and fire dogs decorated with eagles (the Mobilier National, Paris, GML 3600).

Louise-Jeanne, following the fashion for the Enlightenment, was fascinated by Far-Eastern lacquer and porcelain objects. Her cabinet contained more than forty-five Chinese or Japanese lacquer objects and no less than two hundred and fifty oriental porcelain wares—Japanese with Kakiemon decorations or in stoneware, and Chinese celadon wares, in blue and white, with flame motifs, in aubergine or turquoise, and in China white. She loved every kind of Oriental porcelain object. Hence, her different residences were adorned with vases, urns, potpourri vases, cornet vases, fountains, magots, and all kinds of animals, most often decorated with gilded bronze. Her bedroom in the mansion on the Quai Malaquais was entirely decorated with the most luxurious lacquered furniture, in particular a commode with lacquer panels and Sèvres porcelain (English Royal Collections, the porcelain plaque has since been removed, RCIN 35826) complemented by two corner cupboards (English Royal Collections, RCIN 29) made by Joseph Baumhauer and supplied by the dealer Darnault (circa 1718–1790). On this commode are various Chinese porcelain objects from the Kangxi era with a turquoise glaze, notably two large porcelain lions that used to be in the Gaignat Collection (1697–1768) (Gaignat sale, 1768–1769, lot 101) and a pair of vases with embossed carp scale decorations and snake-shaped handles (private collection), which the Duchesse acquired from the marchand-mercier (dealer) Claude-François Julliot (1727–1794) in 1773 (Vriz, S., 2011). The item called the ‘cabinet chinois’ exhibited the largest quantity of Far-Eastern porcelain wares, with eighty-four works, almost all of which were decorated with moulded gilt bronze mounts, such as a pair of celadon vases from the Ming era (1368–1644) dating from the fifteenth century adorned with a Parisian gilded bronze mount dating from circa 1775 (private collection), which she purchased at the Julliot sale in 1777 via the dealer Jean-Baptiste-Pierre Le Brun (1748–1813) (Vriz, S., 2018, pp. 72–79). The Duchess also owned Kyoto stoneware, like the potpourri vase adorned with a mount with satyr heads, which came from the former collection of the painter François Boucher (1703–1770) (private collection) (Vriz, S., 2019, p. 101).

The gradual enrichment of her collections is relatively well known. Indeed, the many records conserved confirm that the Duchesse acquired her objects from the most important Parisian marchands-merciers and during the auctions of major cabinets. Hence, she was a regular customer of Simon-Philippe Poirier (circa 1720–1785) as of 1764, and subsequently of Dominique Daguerre (circa 1740–1796), Claude-François Julliot (1727–1794) as of 1768, and François Charles Darnault (circa 1718–1790) (Farragi, C., 1995). These invoices clearly attest to the fact that the Duchesse readily exchanged objects, had the old gilt-bronze mounts changed for other more modern versions, and even supplied the marchands-merciers with certain porcelain items so that they could create objects that matched her tastes. She also decided to acquire part of her collection through the intermediary of Jean-Baptiste-Pierre Le Brun, a dealer and expert, in particular in lacquer objects and Oriental porcelain wares during the sales of Pierre-Louise-Paul Randon de Boisset (1708–1776) in February 1777, Julliot in November 1777, and the abbot Jean-Bernard Le Blanc (1707–1781) on 14 February 1781.

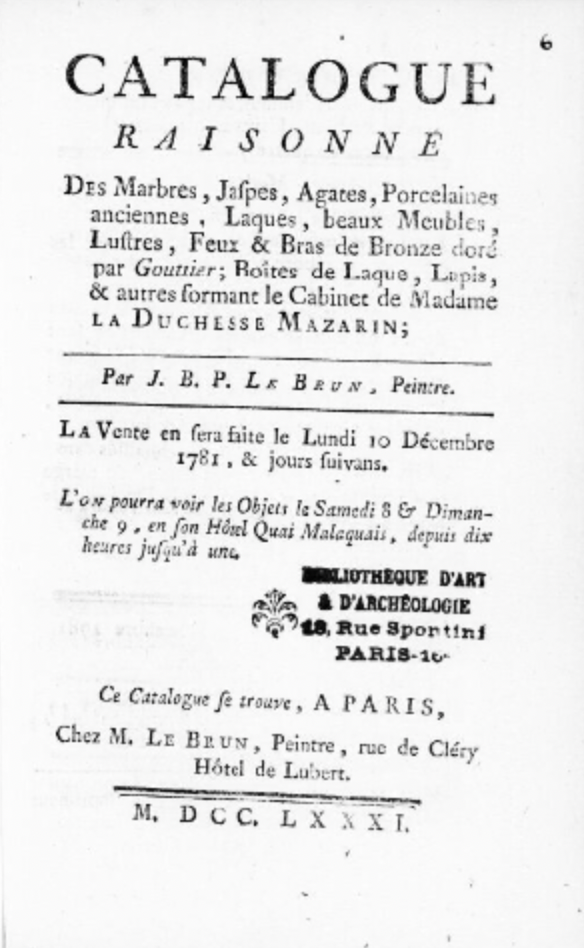

The Duchesse de Mazarin’s Oriental cabinet was very famous in the eighteenth century. During the post-death sale, which was held in her mansion on the Quai Malaquais as of 10 December 1781, the famous dealers and major collectors, such as Queen Marie-Antoinette, fiercely competed with one another over her collection of extremely rare objects. At this sale, the Queen acquired in particular the small kiosk with its Japanese lacquer incense box (Musée du Louvre, Paris, MR380–86; MR380–87) and a hexagonal box also in Japanese lacquer of the inrō–buta–zukuri type (Musée Guimet, Paris, MR380–70).

Related articles

Collection / collection d'une personne

Personne / personne